With the arrival of Apple Pay and Samsung Pay in Russia, many are wondering just how secure these payment systems are, and how popular they are likely to become. A number of experts have commented on this, basing their opinions on the common stereotypes of Android being insecure and the attacks which currently take place on wireless payments. In our opinion however, these technologies require a more detailed examination and a separate evaluation of the threats they face.

The conventional approach

Traditional threats associated with the use of bank cards in ATMs and physical stores have already been studied and described in sufficient detail:

- the magnetic strip can be read using skimmers; modern versions of skimmers are advanced and very inconspicuous;

- to read EMV chips, dedicated skimmers have been designed that are planted into PoS terminals;

- wireless payment technologies (PayPass, PayWave) are potentially vulnerable to remote card reading attacks.

However, the growth in popularity of mobile devices has given rise to a new type of wireless mobile payment: a regular card payment can now be emulated using the smartphone’s built-in NFC antenna. The functionality is turned on at the request of the user, meaning there’s less risk than carrying around a card that’s constantly ready to make a payment. Customers, in turn, don’t have to take out their wallets when making a payment, and don’t even have to carry their bank cards around with them.

The technology for emulating cards on mobile devices (Host Card Emulation, HCE) may have been inexpensive and available to a broad range of device users starting from Android 4.4, but it had several drawbacks:

- the payment terminal had to support wireless payments;

- the eSE (embedded Secure Element) chip made the device more expensive, so initially it was incorporated into just a few top-of-the-range devices from major manufacturers;

- if the manufacturer decided to cut costs on secure data storage, important information ended up being stored by the operating system which could be attacked by malware with root privileges on the device. However, this didn’t go beyond a few proof-of-concept attacks, because there are plenty of other easier ways of attacking mobile banking applications;

- the developers attempted to mitigate the risks associated with storing important payment information on a mobile device, e.g. by storing Secure Element in the cloud. This made smartphone-assisted payments unavailable in locations with unstable mobile data services;

- the risks associated with using software-based HCE storage made it highly advisable to introduce extra security measures into banking applications, making their development more complicated.

As a result, for many large banks, as well as users, paying with the help of card emulation using a smartphone is little more than a quirky feature used for promos or simply to show off in public.

New technologies

The problems described above have given rise to a number of studies, including some by large international companies, in search of more advanced technologies. The next step in the evolution of mobile payments was tokenized payment systems proposed by major market players – Apple, Samsung, and Google. Unlike card emulation on the device, these systems are based on exchanging tokens. A token is a unique transaction ID; the card details are never sent to the payment terminal. This addresses the problem of payment terminals being compromised by malware or skimmers. Unfortunately, this approach has the same problem: the technology has to be implemented by the manufacturer of the payment terminal.

Several years ago, a startup project called LoopPay attempted to address this problem. The developers proposed a kit consisting of a regular card reader for a 3.5 mm (1⁄8 in) audio jack or a phone case. Their know-how was a patented technology for emulating a bank card magnetic strip using a signal generated by their dedicated device. It has to be said that the creators took an early interest in secure data storage (on a dedicated device rather than on the phone) and protection from using the details of other people’s bank cards (personal data checked by comparing information about the user against information from the bank card’s Track 1 information). Later on, Samsung became interested in LoopPay and acquired the startup. After some time, the Magnetic Secure Transmission (MST) technology became available, complementing Samsung Pay tokenized payments. As a result, regular users can use their smartphones to make payments at PoS terminals that support new wireless technologies and use MST at any type of terminal by just placing their device next to the magnetic stripe reader.

We have been watching this project closely, and can now safely say that this technology is, on the whole, a big step forward in terms of convenience and security, because its developers have addressed lots of relevant risks:

- Secure Element is used to reliably store data;

- activation of payment mode on the phone requires the user to enter a PIN code or use a fingerprint;

- on Samsung devices, a KNOX security solution and basic antivirus are pre-installed – these two block payment features when malware compromises the device;

- KNOX Tamper Switch – an object of hate among forum-based “experts” – protects against more serious rootkit malware. KNOX Tamper Switch is a software and hardware appliance that irreversibly blocks the device’s business and payment features during any privilege escalation attacks;

- payment functionality is only available from new devices for which security updates are available, and on which all vulnerabilities are quickly patched;

- on some of the Samsung smartphones sold in Russia, Kaspersky Internet Security for Android is pre-installed. This provides extended protection from viruses and other mobile threats.

It should be noted that Samsung Pay, when making payments, uses a virtual card whose number is not available to the user, rather than the actual banking card tied to the user’s account. This method of payment works just fine when there is no Internet connection.

New old threats

There’s no doubt that the new technology has become an object of interest for security researchers. Potential attacks do exist for it and were presented at the latest BlackHat USA conference. These attacks may still only be potential threats, but we should still stay alert. Russian banks are just planning to introduce biometric authentication on ATMs in 2017, but cybercriminals are already collecting intelligence on which hardware manufacturers are involved, what sort of vulnerabilities exist in the hardware, etc. In other words, the technology is not even available to the wider public yet, but cybercriminals are already searching for weaknesses.

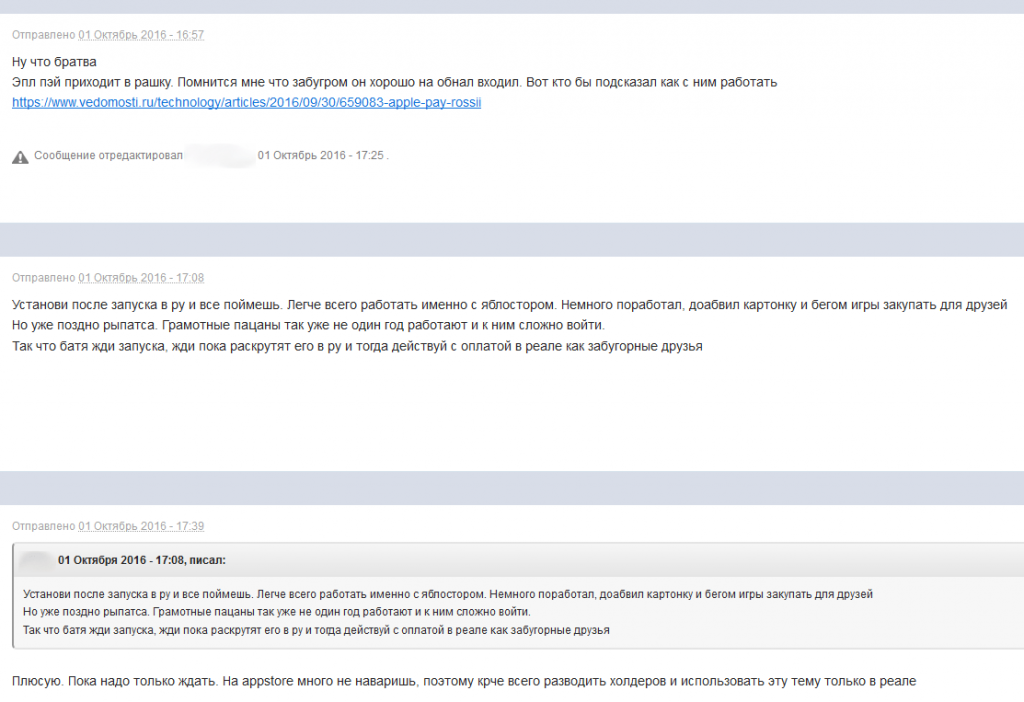

Cybercriminals are also studying Apple and Samsung’s technologies. To makes things worse for Russian users, these technologies only arrive in the Russian market a year after they are launched in Western countries.

Cybercriminals discussing the prospects of exploiting Apple Pay in Russia

At the same time, cybersecurity researchers tend to forget about conventional fraud, which mobile vendors are completely unprepared for as they enter a new sphere of business. Wireless payments have made card fraudsters’ lives much easier both in terms of online trade and shopping in regular stores. They no longer have to use a fake card with stolen card data recorded onto it, and thus run the risk of getting caught at the shop counter – now they can play it much safer by paying for merchandise with a stolen card attached to a top-of-the-range phone.

Alternatively, a fraudster can simply buy merchandise and gift cards in an Apple Store. In spite of all the security measures taken by Apple, the Apple Pay fraud rate in the US was 6% in 2015, or 60 times greater than the 0.1% bank card fraud.

Samsung Pay also sacrificed some of the useful anti-fraud features for usability after it purchased the startup; one being that accounts can be rigidly attached to the cardholder’s name. For instance, I added my own bank card to my smartphone, and then added my colleague’s as well; in the original LoopPay solution, this was impossible.

To conclude, it’s now safe to say that the new tokenized solutions are indeed more secure and convenient compared to their predecessors. However, there’s still plenty of room for improvement when it comes to security, and that’s very important for the future prospects of the technology. After all, no one likes to lose money, be it banks or their clients.

Loop of Confidence