The previous story described an unusual way of distributing malware under disguise of an update for an expired security certificate. After the story went out, we conducted a detailed analysis of the samples we had obtained, with some interesting findings. All of the malware we examined from the campaign was packed with the same packer, which we named Trojan-Dropper.NSIS.Loncom. The malware uses legitimate NSIS software for packing and loading shellcode, and Microsoft Crypto API for decrypting the final payload. Just as the earlier find, this one was not without its surprises, as one of the packaged samples contained software used by APT groups.

Primary analysis

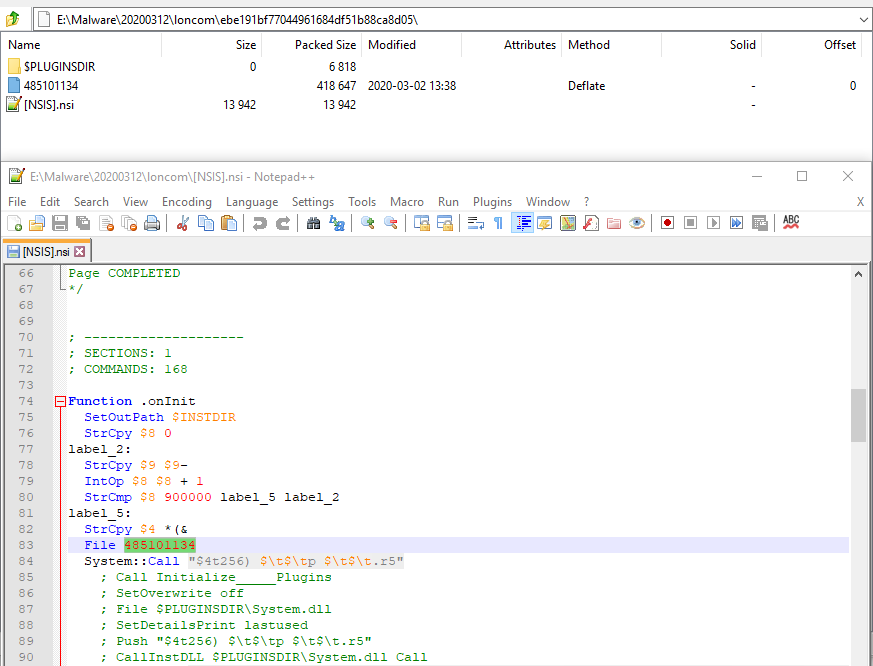

Loncom utilizes NSIS for running shellcode contained in a file with a name that consists of numbers. In our example, the file is named 485101134:

Once the shellcode is unpacked to the hard disk and loaded into the memory, an NSIS script calculates the starting position and proceeds to the next stage.

What the shellcode does

Before proceeding to decrypt the payload, the shellcode starts decrypting itself piece by piece, using the following algorithm:

- Find position for next 0xDEADBEEF dword.

- Read dword: size of data to decrypt.

- Read dword: first part of key.

- Read dword: second part of key.

- Find suitable key: check the numbers consequently, starting at 0, while xor(i, second part of key) != first part of key. This part is needed to hold up execution and prevent AV detection. After simplification, key = i = xor(first part, second part).

- Decrypt next part of shellcode (xor), move on to it.

Here’s the code that performs the algorithm described above:

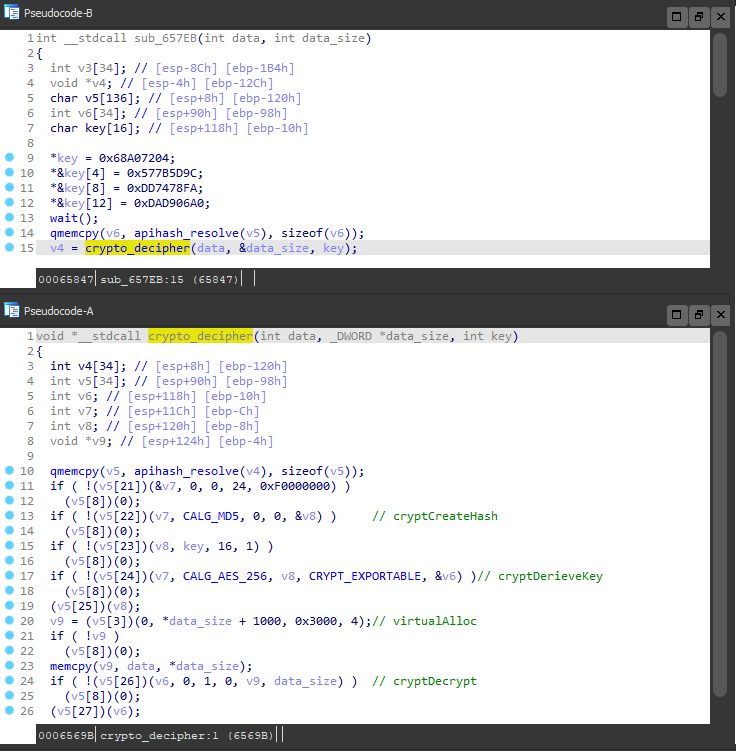

After several such iterations of block decryption, the shellcode switches to active steps, loading libraries and retrieving the addresses of required functions with the help of the APIHashing technique. This helps avoid stating the names of requested functions directly, providing their hashes instead. When searching for functions by hash, a hash will be calculated for each element from the library export table until it matches the target.

Then, Loncom decrypts the payload contained in the same file as the shellcode and proceeds to run it. The payload is encrypted with an AES-256 block cipher. The decryption key is stated in the code, and the payload offset and size are passed from the NSIS script.

Unpacking

For automated Loncom unpacking, we need to find out how data is stored in the packed NSIS installers, obtain the payload offset and size from the NSIS script, and pull the key from the shellcode.

Unpacking the NSIS

After a brief analysis, we managed to find that the NSIS installers have the following structure:

- an MZPE NSIS interpreter containing in its overlay the data to be processed: the flag, the signatures, the size of the unpacked header, and the total size of the data, and then the containers, i.e. the compressed data itself.

- Containers in the following format: dword (data size):zlib_deflate(data). The 0th container has the header, the first container has our file with the shellcode and the payload, and the second one has the DLL with the NSIS plugin.

- The header contains a table of operation codes for the NSIS interpreter, a string table and a language table.

As we have obtained the encrypted file, now all we need is to find the payload offset and size, and proceed to decrypting the payload and the shellcode.

As all arguments in the NSIS operation codes when using plugins are passed as strings, we need to retrieve from the header string table all strings that look like numbers within the logical limits: from 0 to (file size – shellcode size).

NSIS unpacking code:

To simplify determining the payload offset and size, we can recall the structure of the file with the shellcode: encrypted blocks are decrypted from the smallest address to the largest, top to bottom, and the payload is located above the shellcode. Thus, we can determine the position of the 0xDEADBEEF byte and consider it the end of the encrypted data (aligning as required, because AES is a block cipher).

Decrypting the shellcode

To decrypt the payload, we need to:

- decrypt the shellcode blocks;

- determine where the AES key is;

- retrieve the key;

- try to decrypt the payload for offsets received from the NSIS;

- stop after obtaining the first two bytes = ‘MZ’.

Step one can be performed by slightly modifying the code that performs the decryption algorithm in IDA Pro. The key can be determined with the help of a simple regular expression: ‘\xC7\x45.(….)\xC7\x45.(….)\xC7\x45.(….)\xC7\x45.(….)\xE8’ — “mov dword ptr” 4 times, then “call” (pseudocode in the main part of the shellcode).

The other steps do not require a detailed explanation. We will now describe the actual malware that was packed with Loncom.

What’s inside

Besides Mokes and Buerak, which we mentioned in the previous article, we noticed packed specimens of Backdoor.Win32.DarkVNC and Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Sodin families, also known as REvil and Sodinokibi. The first is a type of backdoor used for controlling an infected machine via the VNC protocol. The second is a ransomware that encrypts the victim’s information and threatens to publish it.

However, the most exciting find was the Cobalt Strike utility, used both by legal pentesters and by various APT groups. The command center of the sample that contained Cobalt Strike had previously been seen distributing CactusTorch, a utility for running shellcode present in Cobalt Strike modules, and the same Cobalt Strike packed with a different packer.

We continue monitoring Trojan-Dropper.NSIS.Loncom and hope to share new findings soon.

IOC

BB00BA9726F922E07CF243D3CCFC2B6E (Backdoor.Win32.DarkVNC)

EBE191BF77044961684DF51B88CA8D05 (Backdoor.Win32.DarkVNC)

4B4C98AC8F04680F7C529956CFE8519B (Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Sodin)

AEF8FBB5C64734093E78EB13E6FA7849 (Cobalt Strike)

Loncom packer: from backdoors to Cobalt Strike