Workhorse

Only a few months ago, ChatGPT and other chatbots based on large language models (LLMs) were still a novelty. Users enjoyed using them to compose poems and lyrics in the style of famous artists (which left Nick Cave, for example, decidedly unimpressed), researchers debated blowing up data centers to prevent super AI from unleashing Armageddon, while security specialists persuaded a stubborn chatbot to give them phone-tapping and car-jacking instructions.

Fast forward to today, and many people are already reliant on ChatGPT in their jobs. So much so, in fact, that whenever the service is down (which attracts media coverage), users take to social networks to moan about having to use their brains again. The technology is becoming commonplace, and its inability to keep up with people’s growing demands has led to complaints that the chatbot is gradually getting dumber. Looking at the popularity of the query ChatGPT in Google Trends, we can conclude with some degree of certainty that people mostly seek help from it on weekdays, that is, probably for work matters.

Dynamics of the query ChatGPT in Google Trends, 01.04.2023–30.09.2023, data valid as of 06.10.2023 (download)

The fact that chatbots are actively used for work purposes is confirmed by research data. A Kaspersky survey of people in Russia revealed that 11% of respondents had used chatbots and almost 30% believed that chatbots will take many jobs in the future. Two more surveys we carried out showed that 50% of office workers in Belgium use ChatGPT, and 65% in the UK. Among the latter, 58% use chatbots to save time (for example, for writing up minutes of meetings, extracting the main idea of a text, etc.), 56% for composing new texts, improving style/grammar, as well as for translation, and 35% for analytics (for example, for studying trends). Coders who turn to ChatGPT made up 16%.

Be that as it may, the fact that chatbots are being used more and more in the workplace raises the question: can they be trusted with corporate data? This article delves deep into the settings and privacy policies of LLM-based chatbots to find out how they collect and store conversation histories, and how office workers who use them can protect or compromise company and customer data.

Potential privacy threats

Most LLM-based chatbots (ChatGPT, Microsoft Bing Chat, Google Bard, Anthropic Claude, and others) are cloud-based services. The user creates an account and gains access to the bot. The neural network, a huge resource-intensive system, runs on the side of the provider, meaning the service owner has access to user conversations with the chatbot. Moreover, many services allow you to save chat histories on the server to return to later.

Worryingly, in the UK study mentioned above, 11% of respondents who use ChatGPT at work said they had shared internal documents or corporate data with the chatbot and saw nothing wrong in doing so. A further 17% admitted to sharing private corporate information with chatbots, even though it seemed risky to them.

Given the sensitivity of the data that users share with chatbots, it is worth investigating just how risky this can be. In the case of LLMs, information passed to the bot can be compromised according to several scenarios:

- Data leak or hack on the provider’s side; Although LLM-based chatbots are operated by tech majors, even they are not immune to hacking or accidental leakage. For example, there was an incident in which ChatGPT users were able to see messages from others’ chat histories.

- Data leak through chatbots. Theoretically, user-chatbot conversations could later find their way into the data corpus used for training future versions of the model. Given that LLMs are prone to so-called unintended memorization (memorizing unique sequences like phone numbers that do not improve the quality of the model, but create privacy risks) data that ends up in the training corpus can then be accidentally or intentionally extracted from the model by other users.

- Malicious client. This is particularly relevant in countries where official services like ChatGPT are blocked, and users turn to unofficial clients in the form of programs, websites, and messenger bots. There is nothing to stop the intermediaries from saving the entire chat history and using it for their own purposes; even the client itself could turn out to be malicious.

- Account hacking. Account security is always a priority issue. Even if employees use only official clients, the security of messages potentially containing sensitive data often rests on the owner’s good faith, as does what actual information ends up in the dialog with the chatbot. It is quite possible for attackers to gain access to employee accounts — and the data in them — for example, through phishing attacks or credential stuffing.

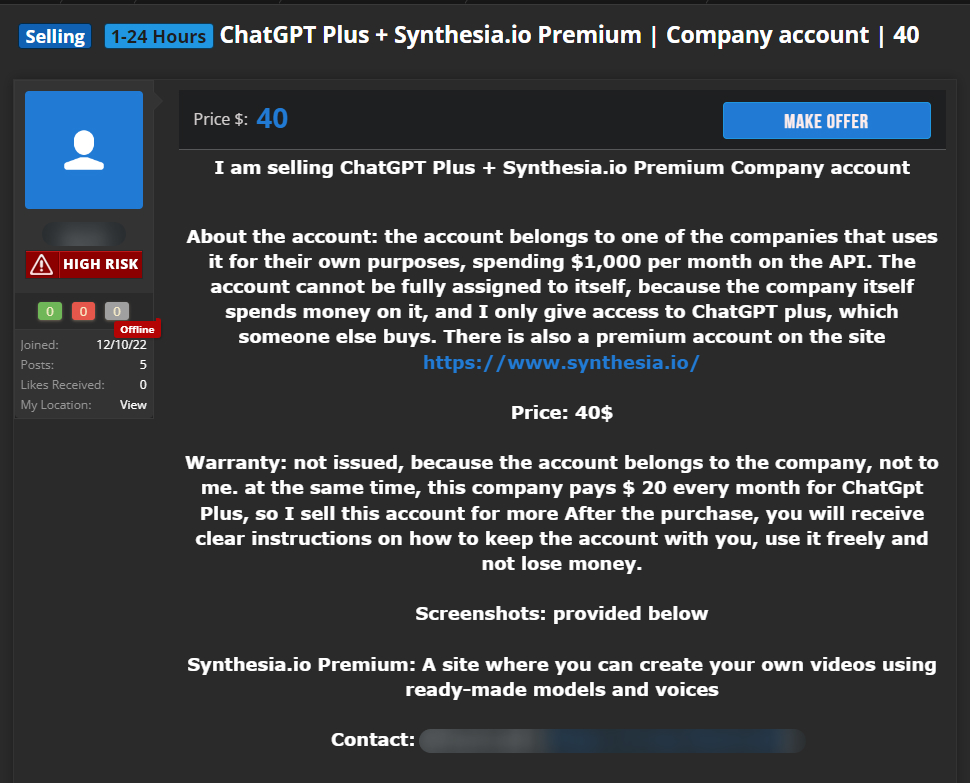

The threat of account hacking is not hypothetical. Kaspersky Digital Footprint Intelligence regularly finds posts on closed forums (including on the dark web) selling access to chatbot accounts:

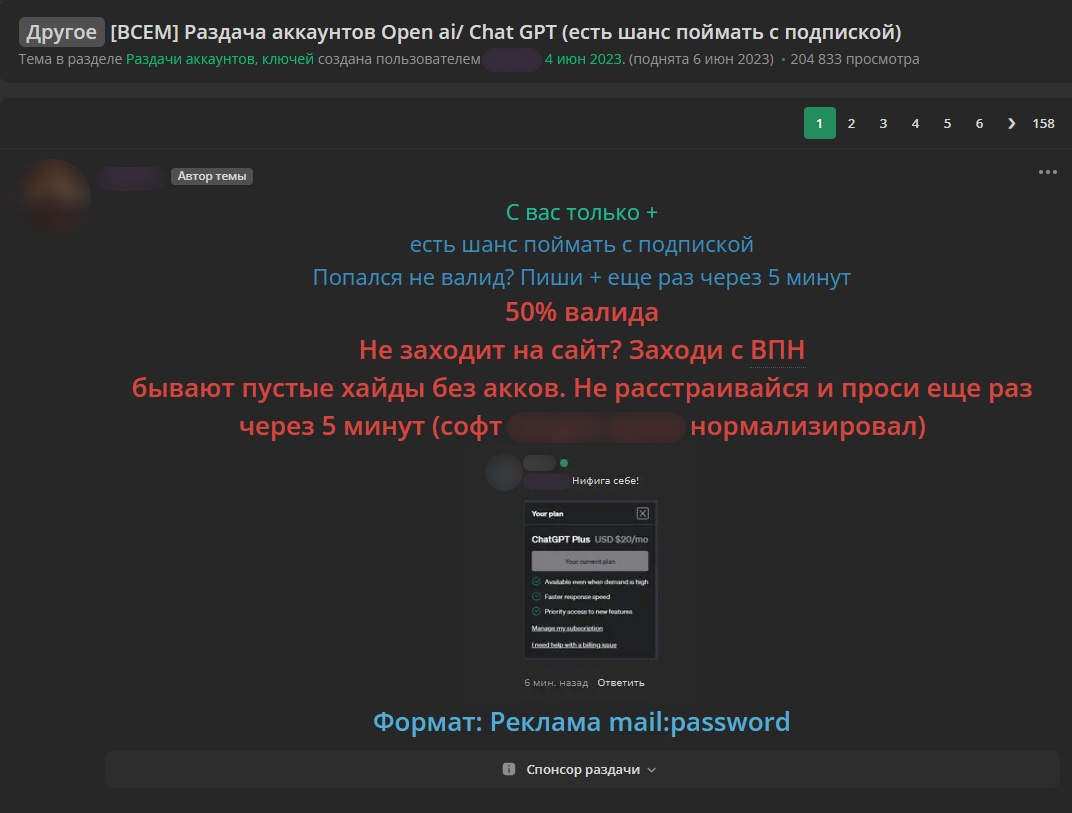

In the screenshot above, the corporate account of a company that pays for a ChatGPT subscription and access to the API is on sale for US$40. Attackers may sell an account for cheaper or even give it away for free, but with no guarantee that it comes with an active subscription:

See translation

[TO ALL] Open ai/ Chat GPT account giveaway (chance to get a subbed one)

All you need to do is +

there’s a chance to get a subbed acc

Got an invalid one? Write + again in 5 minutes

50% are valid

Can’t log into the site? Use a VPN

sometimes there are empty hides without accounts. Don’t get upset and ask again in 5 minutes (the software is #### normalized)

Format: Advertisement mail:password

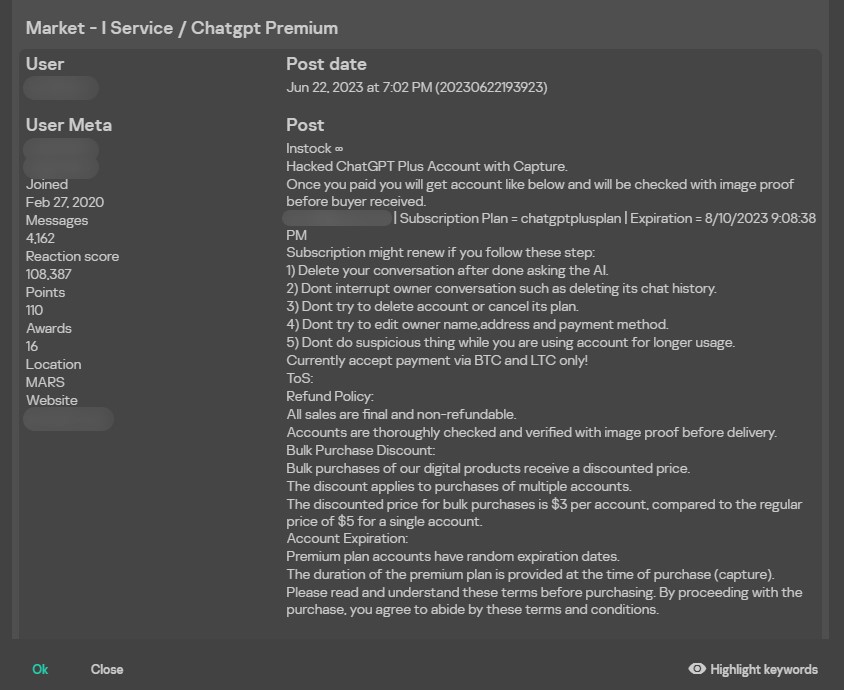

Hackers give buyers instructions on using a compromised account: for example, they recommend not tampering with its owners’ chats and deleting their own messages immediately after each session with the chatbot.

As a result of such a purchase, the cybercriminal buyers get free access not only to the paid resource but also to all chats of the hacked account.

Data privacy issues are a concern for businesses. In May, Samsung Corporation banned its employees from using ChatGPT, according to media reports. In the UK, according to our survey, about 1% of users have faced a total ban on ChatGPT at work, while two-thirds of companies have introduced some kind of workplace policy on the use of generative AI, although 24% of respondents did not feel it was sufficiently clear or comprehensive. To thoroughly protect your business from privacy threats without abandoning chatbots as a tool, you must first analyze the risks relevant to each individual service.

How different chatbots handle user data

There is one very simple but often neglected rule for using any online service: before registering, always read, or at least skim through, the privacy policy. Typically, in the case of bona fide services, this document not only describes what data is collected and how it is used but also clearly spells out the rights of users in relation to the collected data. It is worth knowing this before deciding to entrust your data to the service.

To find out how true the claims are that chatbots are trained on user-supplied prompts, whether all chat histories are saved, and how dangerous it is to use such tools at work, we examined the most popular LLM-based chatbots (ChatGPT, ChatGPT API, Anthropic Claude, Bing Chat, Bing Chat Enterprise, You.com, Google Bard, Genius App by Alloy Studios), analyzed their privacy policies, and tested how securely users are able to protect their accounts in each of them.

On the user side: two-factor authentication and chat history

Among the privacy settings available to the user, we were primarily interested in two questions:

- Does the service save user-chatbot conversations directly in the account?

- How can users protect their accounts from hacking?

In any online service, one of the basic account protections is two-factor authentication (2FA). While the first factor in most cases is a password, the second can be a one-time code sent by text/email or generated in a special app; or it can be something far more complex, such as a hardware security key. The availability of 2FA and its implementation is an important indicator of how much the vendor cares about the security of user data.

Bing Chat and Google Bard require you to sign in using your Microsoft or Google account, respectively. Consequently, the security of conversations with the chatbot on the user side depends on how much your respective account is protected. Both tech giants provide all the necessary tools to protect accounts against hacking on your own: 2FA with various options (app-generated code, by text, and so on); the ability to view activity history and manage devices connected to the account.

Google Bard saves your chat history in your account but lets you customize and delete it. There is a help page with instructions on how to do this. Bing Chat also saves your chat history. The Microsoft Community forum has an answer on how to customize and delete it.

Alloy Studios’ Genius does not require sign-in to the app, but you can only access your chat history on a device with the AppleID you used to subscribe. Therefore, your conversations with the chatbot are protected to the extent that your AppleID is. Genius provides the option to delete any prompts directly in the app interface.

OpenAI’s ChatGPT gives the user the choice of saving their chat history and allowing the model to learn from it, or not saving and allowing. It’s combined in a single setting, so if you want the flexibility of saving chats but excluding them from training, forget it. As for 2FA in ChatGPT, it was available in the settings when our research began, but for some reason, the option later disappeared.

To sign in to You.com, you need to provide an email address to which a one-time code will be sent. Claude (Anthropic) has the same system in place. There are no other authentication factors in these services, so if your email gets hacked, the attackers can easily gain access to your account. You.com saves your chat history, but with some major provisos. Private mode can be enabled in the chatbot interface. The privacy policy has this to say about it: “Private mode: no data collection. Period.” Claude likewise saves your chat history. To find out how to delete it, go to support.anthropic.com.

On the provider side: training the model on prompts and chatbot responses

A major risk associated with using chatbots is leakage of personal data into the bot’s training corpus. Imagine, for instance, you need to evaluate an idea for a new product. You decide to use a chatbot, which you feed a complete description of the idea as input to get the most accurate assessment possible. If the system uses prompts for fine-tuning, your idea winds up in the training corpus, and someone else interested in a similar topic could get a full or partial description of your product in response. Even if the service anonymizes the data before adding it to the corpus, this does not guarantee protection against leakage, since the input text itself has intellectual value. That’s why before using any chatbot, it pays to figure out whether it learns from your prompts and how to stop it.

Conscientious chatbot developers spell out the use of data for model training in their privacy policy. For example, OpenAI employs user-provided content to improve its service but gives you the option to opt out.

As noted above, we may use Content you provide us to improve our Services, for example to train the models that power ChatGPT. See here for instructions on how you can opt out of our use of your Content to train our models.

Note that all conversations with the bot started before you prohibited usage of your data in the settings will be used for subsequent model fine-tuning. Citation:

You can switch off training in ChatGPT settings (under Data Controls) to turn off training for any conversations created while training is disabled or you can submit this form. Once you opt out, new conversations will not be used to train our models.

OpenAI has different rules for businesses and API users. Here it’s the other way round: user-provided data will not be used for model training until the user grants permission.

No. We do not use your ChatGPT Enterprise or API data, inputs, and outputs for training our models.

Bing Chat and Bing Chat Enterprise adopt a similar approach to user data. The document “The new Bing: Our approach to Responsible AI” states:

Microsoft also provides its users with robust tools to exercise their rights over their personal data. For data that is collected by the new Bing, including through user queries and prompts, the Microsoft privacy dashboard provides authenticated (signed in) users with tools to exercise their data subject rights, including by providing users with the ability to view, export, and delete stored conversation history.

So, yes, Bing Chat collects and analyzes your prompts. Regarding data usage, the document reads:

More information about the personal data that Bing collects, how it is used, and how it is stored and deleted is available in the Microsoft Privacy Statement.

A list of data collection purposes can be found at the link, one of which is to “improve and develop our products,” which in the case of a chatbot can be interpreted as model training.

As for Bing Chat Enterprise, here’s what the “Privacy and protections” section says:

Because Microsoft doesn’t retain prompts and responses, they can’t be used as part of a training set for the underlying large language model.

The chatbot of another IT giant, Google Bard, also collects user prompts to improve existing models and train new ones. The Bard Privacy Notice explicitly states:

Google collects your Bard conversations, related product usage information, info about your location, and your feedback. Google uses this data, consistent with our Privacy Policy, to provide, improve, and develop Google products and services and machine learning technologies, including Google’s enterprise products such as Google Cloud.

The Claude (Anthropic) chatbot is another that collects user data but anonymizes it. On the Privacy & Legal page, in response to the question “How do you use personal data in model training?”, it is stated:

We train our models using data from three sources: <…> 3. Data that our users or crowd workers provide.

The same document clarifies further down:

And before we train on Prompt and Output data, we take reasonable efforts to de-identify it in accordance with data minimization principles.

You.com, as we already mentioned, has two modes: private and standard. In private mode, as per the company’s privacy policy, no data is collected. In standard mode, all information about interactions with the service is collected. The text does not explicitly state that means the collection of your prompts, but nor does it deny it.

Information We Collect in Standard Mode. <…> Usage Information. To help us understand how you use our Services and to help us improve them, we automatically receive information about your interactions with our Services, like the pages or other content you view, and the dates and times of your visits. Private mode differs significantly from this as described above.

Since the collected data is used to improve the service, it cannot be ruled out that it gets used for model training. The “How We Use the Information We Collect in Standard mode” section additionally states: “To provide, maintain, improve, and enhance our Services”;

Alloy Studios’ Genius likewise fails to give a straight answer to the question of whether prompts are collected and used to train models. The privacy policy employs generic formulations with no specifics relevant to our study:

We collect certain information that your mobile device sends when you use our services <…> as well as information about your use of our services through your device.

Such wording may indicate that the service collects the prompts to the chatbot, but there is no hard proof. Regarding the use of the above-mentioned information, the company’s privacy policy states the following:

We use the information we collect to provide our services, to respond to inquiries, to personalize and improve our services and your experiences when you use our services.

To sum up, as we have seen, solutions for business are generally quite secure. In the B2B segment, the security and privacy requirements are higher, as are the risks from corporate information leakage. Consequently, the data usage, collection, storage, and processing terms and conditions are more geared toward protection than in the B2C segment. The B2B solutions in this study do not save chat histories by default, and in some cases, no prompts at all get sent to the servers of the company providing the service, as the chatbot is deployed locally in the customer’s network.

As for custom chatbots, unfortunately, they are not suitable for work tasks involving internal corporate or confidential data. Some do allow you to set strict privacy settings or work in private mode, but even they pose certain risks. For example, an employee may forget about the settings or accidentally reset them. Moreover, they provide no option for centralized control over user accounts. For an employer, it makes more financial sense to purchase a business solution, if required, than to suffer from a leak of confidential information due to employees using a chatbot on the sly. Which they will do.

User rights regarding personal data

We’ve looked at what tools users have at their disposal for self-protection against unauthorized access to their data, what can be done with chat histories, and whether LLM developers really train their models on user data. Now let’s figure out what rights users have with regard to the information they feed the chatbot.

Such information is typically found in the privacy policy under the “Your rights” section or similar. When analyzing this section, pay attention to its compliance with the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) on how information is to be provided and what rights are to be granted to users (laid out in Chapter 3). Even if you live outside the EU and the scope of the GDPR, compliance with the regulation indicates the integrity of the service.

One of the GDPR’s core requirements is that information about user rights be provided in a concise, transparent, intelligible, and easily accessible form. The list of necessary rights includes the right to correct, delete, and obtain a copy of collected personal data, as well as to opt out of its processing. The right to delete is particularly useful if you no longer need this service.

Almost all of the companies reviewed in this study provide user rights in their privacy policies in a fairly transparent and readable form. OpenAI gives this information under 4. Your rights. The company allows you to retrieve, delete, and correct collected data, and restrict or opt out of its processing. Claude (Anthropic) sets out user rights under 5. Rights and Choices. These include the right to know what information the company collects, as well as to access, correct, delete, and opt out of providing data. Microsoft Bing Chat has a fair amount of information in the “How to access and control your personal data” section about how and where you can correct or delete data, but there is no explicit list of user rights in accordance with the GDPR. Google provides detailed instructions on how, where, and what you can do with your data on its Privacy & Terms page in the “Your privacy controls” and “Exporting and deleting your information” sections.

You.com has no special section listing user rights. The only place where they even get a mention comes at the end of the “How We Use the Information We Collect in Standard mode” section:

You are in control of your information:

You can unsubscribe from our promotional emails via the link provided in the emails. Even if you opt-out of receiving promotional messages from us, you will continue to receive administrative messages from us.

You can request the deletion of your user profile and all data associated to it by emailing us at legal@you.com.

The Genius privacy policy has no mention of user rights whatsoever.

Note, however, that the mere mention of user rights in the privacy policy does not guarantee compliance. Your actual options will depend on the jurisdiction you live under and the extent to which local law protects your data. Nevertheless, as we mentioned above, compliance with regulations such as GDPR indicates how reliable the service is.

Conclusion

We have examined the main threats arising from the use of LLM-based chatbots for work purposes and found that the risk of sensitive data leakage is highest when employees use personal accounts at work.

This makes raising staff awareness of the risks of using chatbots a top priority for companies. On the one hand, employees need to understand what data is confidential or personal, or constitutes a trade secret, and why it must not be fed to a chatbot. On the other, the company must spell out clear rules for using such services, if they are allowed at all. Equally important is awareness of potential phishing attacks looking to exploit the popularity of the generative AI topic.

Ideally, if a company sees benefits in allowing employees to use chatbots, it should use business solutions with a clear data storage mechanism and a centralized management option. If you trust the use of chatbots and account security to employees themselves, you run the risk of a data breach due to the wide variance in privacy policies and account security levels. To prevent employees from independently consulting untrusted chatbots for work purposes, you can use a security solution with cloud service analytics. Among its features, our Kaspersky Endpoint Security Cloud includes Cloud Discovery for managing cloud services and assessing the risks of using them.

ChatGPT at work: how chatbots help employees, but threaten business

Shahid

I like it very much

Anonymous

Would have been better to also catalog and tabulate the product by unique marketing name, data privacy policies, and links so people could easily understand what brands have what privacy capabilities. There are too many anecdotal failures here, that by definition are temporary issues, to easily understand which products are dedicated to enterprise privacy and which are not.

Securelist

Hi Anonymous,

The information provided in this post was relevant at the time of writing. However, privacy policies do change over time. To help business keep track of all the changes, we implemented Cloud Discovery feature in our products: https://support.kaspersky.com/Cloud/1.0/en-US/126963.htm