This is Kaspersky Lab’s annual threat analysis report covering the major issues faced by corporate and individual users alike as a result of malware, potentially harmful programs, crimeware, spam, phishing and other different types of hacker activity.

The report has been prepared by the Global Research & Analysis Team (GReAT) in conjunction with Kaspersky Lab’s Content & Cloud Technology Research and Anti-Malware Research divisions.

The 10 Security Stories That Shaped 2012

At the end of last year we published “The Top 10 Security Stories of 2011“, an article that summarized 2011 in one word: “explosive”. Back then, the biggest challenge was how to narrow down all the incidents, stories, facts, new trends and intriguing actors into just 10 top stories.

Based on the events and the actors who defined the top security stories of 2011, we made a number of predictions regarding 2012:

- The continued rise of hacktivist groups.

- The growth of Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) incidents

- The dawn of cyber-warfare and more powerful nation states jostling for dominance through cyber-espionage campaigns.

- Attacks on software and gaming developers such as Adobe, Microsoft, Oracle and Sony.

- More aggressive actions from law enforcement agencies against traditional cybercriminals.

- An explosion of Android threats.

- Attacks on Apple’s Mac OS X platform.

How did we fare in our predictions? Let’s take a look at the top 10 security incidents that shaped 2012…

1. Flashback hits Mac OS X

Although the Mac OS X Trojan Flashback/Flashfake

appeared in late 2011, it wasn’t until April 2012 that it became really popular. And when we say really popular, we mean really popular. Based on our statistics, we estimate that Flashback infected over 700,000 Macs, easily the biggest known MacOS X infection to date. How was this possible? Two main factors: a Java vulnerability CVE-2012-0507 and the general sense of apathy among the Mac faithful when it comes to security issues.

Flashback continues to be relevant because it demolished the myth of invulnerability surrounding the Mac and because it confirmed that massive outbreaks can indeed affect non-Windows platforms. Back in 2011, we predicted that we would see more Mac malware attacks. We just never expected it would be this dramatic.

2. Flame and Gauss: nation-state cyber-espionage campaigns

In mid-April 2012, a series of cyber-attacks destroyed computer systems at several oil platforms in the Middle East. The malware responsible for the attacks, named “Wiper”, was never found – although several pointers indicated a resemblance to Duqu and Stuxnet. During the investigation, we stumbled upon a huge cyber-espionage campaign now known as Flame.

Flame is arguably one of the most sophisticated pieces of malware ever created. When fully deployed onto a system, it has more than 20 MB of modules which perform a wide array of functions such as audio interception, bluetooth device scanning, document theft and the making of screenshots from the infected machine. The most impressive part was the use of a fake Microsoft certificate to perform a man-in-the-middle attack against Windows Updates, which allowed it to infect fully patched Windows 7 PCs at the blink of an eye. The complexity of this operation left no doubt that this was backed by a nation-state. Actually, a strong connection to Stuxnet was discovered by Kaspersky researchers, which indicate the Flame developers worked together with Stuxnet developers, perhaps during the same operation.

Flame is important because it showed that highly complex malware can exist undetected for many years. It is estimated that the Flame project could be at least five years old. It also redefined the whole idea of “zero-days”, through its “God mode” man-in-the-middle propagation technique.

Of course, when Flame was discovered, people wondered how many other campaigns like this were being mounted. And it wasn’t long before others surfaced. The discovery of Gauss, another highly sophisticated Trojan that was widely deployed in the Middle East, added a new dimension to nation-state cyber campaigns. Gauss is remarkable for a variety of things, some of which remain a mystery to this day. The use of a custom font named “Palida Narrow” or its encrypted payload which targets a computer disconnected from the Internet are among the many unknowns. It is also the first government-sponsored banking Trojan with the ability to hijack online banking credentials from victims, primarily in Lebanon.

With Flame and Gauss, a new dimension was injected into the Middle East battleground: cyber-war and cyber-warfare. It appears there is a strong cyber component to the existing geopolitical tensions – perhaps bigger than anyone expected.

3. The explosion of Android threats

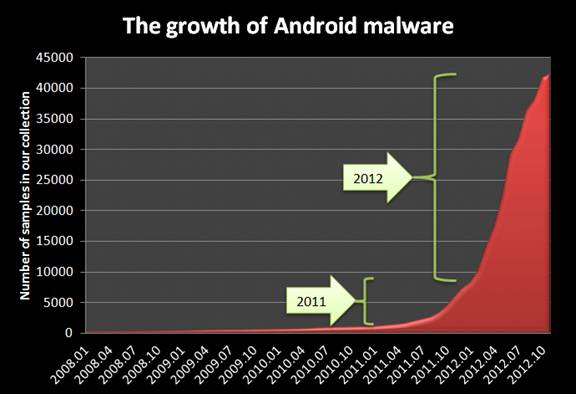

During 2011, we witnessed an explosion in the number of malicious threats targeting the Android platform. We predicted that the number of threats for Android will continue to grow at an alarming rate. The chart below clearly confirms this:

The number of samples we received continued to grow and peaked in June 2012, when we identified almost 7,000 malicious Android programs. Overall, in 2012, we identified more than 35,000 malicious Android programs, which is about six times more than in 2011. That’s also about five times more than all the malicious Android samples we’ve received since 2005 altogether!

The reason for the huge growth of Android can be explained by two factors: economic and platform related. First of all, the Android platform itself has become incredibly popular, becoming the most widespread OS for new phones, with over 70% market share. Secondly, the open nature of the operating system, the ease with which apps can be created and the wide variety of (unofficial) application markets have combined to shine a negative spotlight on the security posture of the Android platform.

Looking forward, there is no doubt this trend will continue, just like it did with Windows malware many years ago. We are therefore expecting 2013 to be filled with targeted attacks against Android users, zero-days and data leaks.

4. The LinkedIn, Last.fm, Dropbox and Gamigo password leaks

On 5 June 2012, LinkedIn, one of the world’s biggest social networks for business users was hacked by unknown assailants and the password hashes of more than 6.4 million people leaked onto the Internet. Through the use of fast GPU cards, security researchers recovered an amazing 85% of the original passwords. Several factors made this possible. First of all, LinkedIn stored the passwords as SHA1 hashes. Although better than the very popular MD5, modern GPU cards can crack SHA1 hashes at incredible speeds. For instance, a $400 Radeon 7970 can check close to 2 billion SHA1 password/hashes per second. This, combined with modern cryptographic attacks such as the usage of Markov chains to optimize brute force search or mask attacks, taught web developers some new lessons about storing encrypted passwords.

When DropBox announced that it was hacked and user account details were leaked, it was yet another confirmation that hackers were targeting valuable data (especially user credentials) at popular web services. In 2012, we saw similar attacks at Last.fm and Gamigo, where more than 8 million passwords were leaked to the public.

To get an idea of how big a problem this is, during the InfoSecSouthwest 2012 conference, Korelogic released an archive containing about 146 million password hashes, which was put together from multiple hacking incidents. Of these, 122 million were already cracked.

These attacks show that in the age of the ‘cloud’, when information about millions of accounts is available in one server, over speedy internet links, the concept of data leaks takes on new dimensions. We explored this last year during the Sony Playstation Network hack; there is perhaps no surprise such huge leaks and hacks continued in 2012.

5. The Adobe certificates theft and the omnipresent APT

During 2011, we saw several high profile attacks against certificate authorities. In June, DigiNotar, a Dutch company, was hacked out of business, while a Comodo affiliate was tricked into issuing digital certificates in March. The discovery of Duqu in September 2011 was also related to a Certificate Authority hack.

On 27 September 2012, Adobe announced the discovery of two malicious programs that were signed using a valid Adobe code signing certificate. Adobe’s certificates were securely stored in an HSM, a special cryptographic device which makes attacks much more complicated. Nevertheless, the attackers were able to compromise a server that was able to perform code signing requests.

This discovery belongs to the same chain of extremely targeted attacks performed by sophisticated threat actors commonly described as APT.

The fact that a high profile company like Adobe was compromised in this way redefines the boundaries and possibilities that are becoming available for these high-level attackers.

6. The DNSChanger shutdown

When the culprits behind the DNSChanger malware were arrested in November 2011 during the “Ghost Click” operation, the identity-theft infrastructure was taken over by the FBI.

The FBI agreed to keep the servers online until 9 July 2012, so the victims could have time to disinfect their systems. Several doomsday scenarios aside, the date passed without too much trouble. This would not have been possible without the time and resources invested into the project by the FBI, as well as other law enforcement agencies, private companies and governments around the world. It was a large scale action that showed that success against cybercrime can be achieved through open cooperation and information sharing.

7. The Ma(h)di incident

During late 2011 and the first half of 2012, an ongoing campaign to infiltrate computer systems throughout the Middle East targeted individuals across Iran, Israel, Afghanistan and others scattered across the globe. In partnership with Seculert, we thoroughly investigated this operation and named it “Madi”, based on certain strings and handles used by the attackers.

Although Madi was relatively unsophisticated, it did succeed in compromising many different victims around the globe through social engineering and Right-To-Left-Override tactics. The Madi campaign demonstrated yet another dimension to cyber-espionage operations in the Middle East and one very important thing: low investment operations, as opposed to nation-state sponsored malware with an unlimited budget, can be quite successful.

8. The Java 0-days

In the aftermath of the previously mentioned Flashback incident, Apple took a bold step and decided to disable Java across millions of Mac OS X users. It might be worth pointing out that although a patch was available for the vulnerability exploited by Flashback since February, Apple users were exposed for a few months because of Apple’s tardiness in pushing the patch to Mac OS X users. The situation was different on Mac OS X, because while for Windows, the patches came from Oracle, on Mac OS X, the patches were delivered by Apple.

If that was not enough, in August 2012, a Java zero-day vulnerability was found to be massively used in-the-wild (CVE-2012-4681). The exploit was implemented in the wildly popular BlackHole exploit kit and quickly become the most effective of the whole set, responsible for millions of infections worldwide.

During the second quarter of 2012, we performed an analysis of vulnerable software found on users’ computers and found that more than 30% had an old and vulnerable version of Java installed. It was easily the most widespread vulnerable software installed.

9. Shamoon

In the middle of August, details appeared about a piece of highly destructive malware that was used in an attack against Saudi Aramco, one of the world’s largest oil conglomerates. According to reports, more than 30,000 computers were completely destroyed by the malware.

We analyzed the Shamoon malware and found that it contained a built-in switch which would activate the destructive process on 15 August, 8:08 UTC. Later, reports emerged of another attack of the same malware against another oil company in the Middle East.

Shamoon is important because it brought up the idea used in the Wiper malware, which is a destructive payload with the purpose of massively compromising a company’s operations. As in the case of Wiper, many details are unknown, such as how the malware infected the systems in the first place or who was behind it.

10. The DSL modems, Huawei banning and hardware hacks

In October 2012, Kaspersky researcher Fabio Assolini published the details of an attack which had been taking place in Brazil since 2011 using a single firmware vulnerability, two malicious scripts and 40 malicious DNS servers. This operation affected six hardware manufacturers, resulting in millions of Brazilian internet users falling victim to a sustained and silent mass attack on DSL modems.

In March 2012, Brazil’s CERT team confirmed that more than 4.5 million modems were compromised in the attack and were being abused by cybercriminals for all sorts of fraudulent activity.

At the T2 conference in Finland, security researcher Felix ‘FX’ Lindner of Recurity Labs GmbH discussed the security posture and vulnerabilities discovered in the Huawei family of routers. This came in the wake of the U.S. government’s decision to investigate Huawei for espionage risks (http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-18560_162-57527441/huawei-probed-for-security-espionage-risk/).

The case of Huawei and the DSL routers in Brazil are not random incidents. They are just indications that hardware routers can pose the same if not higher security risks as older or obscure software that is never updated. They indicate that defense has become more complex and more difficult than ever – in some cases, even impossible.

Conclusions: From Explosive to Revealing and Eye-opening

As we turn the page to 2013, we’re all wondering what’s next. As we can see from the top 10 stories above, we were very much on the ball with our predictions.

Despite the arrest of LulzSec’s Xavier Monsegur and many prominent ‘Anonymous’ hackers, the hacktivists continued their activities. The cyber-warfare/cyber-espionage campaigns grew to new dimensions with the discovery of Flame and Gauss. APT operations continued to dominate the news, with zero-days and clever attack methods being employed to hack high-profile victims. Mac OS X users were dealt a blow by Flashfake, the biggest Mac OS X epidemic to date while big companies fought against destructive malware that wrecked tens of thousands of PCs.

The powerful actors from 2011 remained the same: hacktivist groups, IT security companies, nation states fighting each other through cyber-espionage, major software and gaming developers such as Adobe, Microsoft, Oracle or Sony, law enforcement agencies and traditional cybercriminals, Google, via the Android operating system, and Apple, thanks to its Mac OS X platform.

We categorized 2011 as “explosive” and we believe the incidents in 2012 raised eyebrows and piqued the imagination. We came to understand the new dimensions in existing threats while new attacks are beginning to take shape.

Security forecast for 2013

The end of the year is traditionally a time for reflection – for taking stock of our lives and looking to the future. So we’d like to offer you our forecast for the year ahead, looking at the key issues that we believe are likely to dominate the security landscape in 2013. Of course, the future is always rooted in the present, so our security retrospective, outlining the key trends of 2012, is a good starting-point.

1. Targeted attacks and cyber-espionage

While the threat landscape is still dominated by random, speculative attacks designed to steal personal information from anyone unlucky enough to fall victim to them, targeted attacks have become an established feature in the last two years. Such attacks are specifically tailored to penetrate a particular organization and are often focused on gathering sensitive data that has a monetary value in the ‘dark market’. Targeted attacks can often be highly sophisticated. But many attacks start by ‘hacking the human’, i.e. by tricking employees into disclosing information that can be used to gain access to corporate resources. The huge volume of information shared online and the growing use of social media in business has helped to fuel such attacks – and staff with public-facing roles (for example, those with sales or marketing roles within a company) can be particularly vulnerable. We can expect the growth of cyber-espionage to continue into 2013 and beyond. It’s easy to read the headlines in the computer press and imagine that targeted attacks are a problem only for large organizations, particularly those that maintain ‘critical infrastructure’ systems within a country. However, any organization can become a victim. All organizations hold data that is of value to cybercriminals; and they may also be used as ‘stepping-stones’ to reach other companies.

2. The onward march of ‘hacktivism’

Stealing money – either by directly accessing bank accounts or by stealing confidential data – is not the only motive behind attacks. Sometimes the purpose of an attack is to make a political or social point. There was a steady stream of such attacks this year. This included the DDoS attacks launched by Anonymous on government websites in Poland, following the government’s announcement that it would support ACTA (the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement); the hacking of the official F1 website in protest against the treatment of anti-government protesters in Bahrain; the hacking of various oil companies in protest against drilling in the Arctic; the attack on Saudi Aramco; and the hacking of the French Euromillions website in a protest against gambling. Society’s increasing reliance on the Internet makes organizations of all kinds potentially vulnerable to attacks of this sort, so ‘hacktivism’ looks set to continue into 2013 and beyond.

3. Nation-state-sponsored cyber-attacks

Stuxnet pioneered the use of highly sophisticated malware for targeted attacks on key production facilities. However, while such attacks are not commonplace, it’s now clear that Stuxnet was not an isolated incident. We are now entering an era of cold ‘cyber-war’, where nations have the ability to fight each other unconstrained by the limitations of conventional real-world warfare. Looking ahead we can expect more countries to develop cyber weapons – designed to steal information or sabotage systems – not least because the entry-level for developing such weapons is much lower than is the case with real-world weapons. It’s also possible that we may see ‘copy-cat’ attacks by non-nation-states, with an increased risk of ‘collateral damage’ beyond the intended victim of the attack. The targets for such cyber-attacks could include energy supply and transportation control facilities, financial and telecommunications systems and other ‘critical infrastructure’ facilities.

4. The use of legal surveillance tools

In recent years, cybercrime has become more and more sophisticated. This has not only created new challenges for anti-malware researchers, but also for law enforcement agencies around the world. Their efforts to keep pace with the advanced technologies being used by cybercriminals are driving them in directions that have obvious implications for law enforcement itself. This includes, for example, what to do about compromised computers after the authorities have successfully taken down a botnet – as in the case of the FBI’s Operation Ghost Click, which we discussed here. But it also includes using technology to monitor the activities of those suspected of criminal activities. This is not a new issue – consider the controversy surrounding ‘Magic Lantern’ and the ‘Bundestrojan’. More recently, there has been debate around reports that a UK company offered the ‘Finfisher’ monitoring software to the previous Egyptian government and reports that the Indian government asked firms (including Apple, Nokia and RIM) for secret access to mobile devices. Clearly, the use of legal surveillance tools has wider implications for privacy and civil liberties. And as law enforcement agencies, and governments, try to get one step ahead of the criminals, it’s likely that the use of such tools – and the debate surrounding their use – will continue.

5. Cloudy with a chance of malware

It’s clear that the use of cloud services will grow in the coming years. There are two key factors driving the development of these services. The first is cost. The economies of scale that can be achieved by storing data or hosting applications in the cloud can result in significant savings for any business. The second is flexibility. Data can be accessed any time, any place, anywhere – and from any device, including laptops, tablets and smartphones. But as the use of the cloud grows, so too will the number of security threats that target it. First, the data centers of cloud providers form an attractive target for cybercriminals. ‘The cloud’ may sound fluffy and comfortable as a concept, but let’s not forget that we’re talking about data that’s stored on real servers in the physical world. Looked at from the perspective of a cybercriminal, they offer a potential single-point-of-failure. They hold large quantities of personal data in one place that can be stolen in one fell swoop if the provider should fall victim to a successful attack. Second, cybercriminals are likely to make more use of cloud services to host and spread their malware – typically through stolen accounts. Third, we should also remember that data stored in the cloud is accessed from a device in the ‘non-cloud’ world. So if a cybercriminal is able to compromise the device, they can gain access to the data – wherever it’s stored. The wide use of mobile devices, while offering huge benefits to a business, also increases the risk – cloud data can be accessed from devices that may not be as secure as traditional endpoint devices.

When the same device is used for both personal and business tasks, that risk increases still further.

6. Dude, where’s my privacy?!

The erosion, or loss, of privacy has become a hotly-debated issue in IT security. The Internet pervades our lives and many people routinely bank, shop and socialize online. Every time we sign up for an online account, we are required to disclose information about ourselves and companies around the world actively gather information about their customers. The threat to privacy takes two forms. First, personal data is put at risk if anything compromises the providers of goods and services we do business with. Hardly a week goes by without a news story about a company that has fallen victim to hackers, exposing the personal data of its customers. Of course, the further development of cloud-based services will only exacerbate this problem. Second, companies aggregate and use the information they hold about us for advertising and promotional purposes, sometimes without us even knowing about it, and it’s not always clear how to opt out of this process. The value of personal data – to cybercriminals and legitimate businesses – will only grow in the future, and with it the potential threat to our privacy increases.

7. Who do you trust?

If someone knocks on your front door and asks you to let them in, you’d probably be very reluctant to do so if they can’t show you a valid form of ID. But what if they do? And what if their ID isn’t fake, but a real ID from a legitimate organization? This would undermine the trust process that we’re all encouraged to rely on to keep us safe from real-world fraudsters. The same is true in the online world. We’re all predisposed to trust websites with a security certificate issued by a bona fide Certificate Authority (CA), or an application with a valid digital certificate. Unfortunately, not only have cybercriminals been able to issue fake certificates for their malware – using so-called self-signed certificates – they have also been able to successfully breach the systems of various CAs and use stolen certificates to sign their code. The use of fake, and stolen, certificates is set to continue in the future. The problem may well be compounded by a further development. In recent years, allowlisting has been added to the arsenal of security vendors – that is, checking code not only to see if it’s known to be malicious, but also checking to see if it’s ‘known-good’. But if rogue applications find their way onto a allowlist, they could ‘fly under the radar’ of security programs and go undetected. This could happen in several ways. The malware might be signed using a stolen certificate: if the allowlist application automatically trusts software signed by that organization, the infected program might also be trusted. Or cybercriminals (or someone inside a company) may gain access to the directory, or database, holding the allowlist and add their malware to the list. A trusted insider – whether in the real world or the digital world – is always well placed to undermine security.

8. Cyber extortion

This year we have seen growing numbers of ransomware Trojans designed to extort money from their victims, either by encrypting data on the disk or by blocking access to the system. Until fairly recently this type of cybercrime was confined largely to Russia and other former Soviet countries. But they have now become a worldwide phenomenon, although sometimes with slightly different modus operandi. In Russia, for example, Trojans that block access to the system often claim to have identified unlicensed software on the victim’s computer and ask for a payment. In Europe, where software piracy is less common, this approach is not as successful. Instead, they masquerade as popup messages from law enforcement agencies claiming to have found child pornography or other illegal content on the computer. This is accompanied by a demand to pay a fine. Such attacks are easy to develop and, as with phishing attacks, there seem to be no shortage of potential victims. As a result, we’re likely to see their continued growth in the future.

9. Mac OS malware

Despite well-entrenched perceptions, Macs are not immune to malware. Of course, when compared with the torrent of malware targeting Windows, the volume of Mac-based malware is small. However, it has been growing steadily over the last two years; and it would be naïve of anyone using a Mac to imagine that they could not become the victim of cybercrime. It’s not only generalised attacks – such as the 700,000-strong Flashfake botnet – that pose a threat; we have also seen targeted attacks on specific groups, or individuals, known to use Macs. The threat to Macs is real and is likely keep growing.

10. Mobile malware

Mobile malware has exploded in the last 18 months. The lion’s share of it targets Android-based devices – more than 90 per cent is aimed at this operating system. Android OS ‘ticks all the boxes’ for cybercriminals: it’s widely used, it’s easy to develop for, and those using the system are able to download programs (including malicious programs) from wherever they choose. For this reason, there is unlikely to be any slow-down in the development of malicious apps for Android. To date, most malware has been designed to get access to the device. In the future, we are likely to see the use of vulnerabilities that target the operating system and, based on this, the development of ‘drive-by downloads’. There is also a high probability that the first mass worm for Android will appear, capable of spreading itself via text messages and sending out links to itself at some online app store. We’re also likely to see more mobile botnets, of the sort created using the RootSmart backdoor in Q1 2012. By contrast, iOS is a closed, restricted file system, allowing the download and use of apps from just a single source – i.e. the App Store. This means a lower security risk: in order to distribute code, would-be malware writers would have to find some way of ‘sneaking’ code into the App Store. The appearance of the ‘Find and Call’ app earlier this year has shown that it’s possible for undesirable apps to slip through the net. But it’s likely that, for the time being at least, Android will remain the chief focus of cybercriminals. The key significance of the ‘Find and Call’ app lies in the issue of privacy, data leakage and the potential damage to a person’s reputation: this app was designed to upload someone’s phone book to a remote server and use it to send SMS spam.

11. Vulnerabilities and exploits

One of the key methods used by cybercriminals to install malware on victims’ computers is to exploit un-patched vulnerabilities in applications. This relies on the existence of vulnerabilities and the failure of individuals or businesses to patch their applications. Java vulnerabilities currently account for more than 50 per cent of attacks, while Adobe Reader accounts for a further 25 per cent. This isn’t surprising, since cybercriminals typically focus their attention on applications that are widely used and are likely to be un-patched for the longest time – giving them a sufficient window of opportunity to achieve their goals. Java is not only installed on many computers (1.1 billion, according to Oracle), but updates are installed on demand, not automatically. For this reason, cybercriminals will continue to exploit Java in the year ahead. It’s likely that Adobe Reader will also continue to be used by cybercriminals, but probably less so because the latest versions provide an automatic update mechanism.

Kaspersky Security Bulletin 2012. Malware Evolution