- Kaspersky Security Bulletin 2009. Malware Evolution 2009

- Kaspersky Security Bulletin 2009. Statistics, 2009

- Kaspersky Security Bulletin: Spam Evolution 2009

Trends

2009 was the latest milestone both in the history of malware and in the history of cybercrime, with a marked change in direction in both areas. This year laid the foundation of what we will see in the future.

In 2007 – 2008, the creation of non-commercial malware almost died out. The main type of malware was data-stealing Trojans, and cybercriminals paid particular attention to data belonging to online gamers – their passwords, their characters, and their in-game assets.

Over the last 3-4 years, China has become the leading source of malware. Chinese cybercriminals have shown themselves to be capable of creating such huge volumes of malware that over the last two years, antivirus companies have, without exception, put most of their effort into combating Chinese malware.

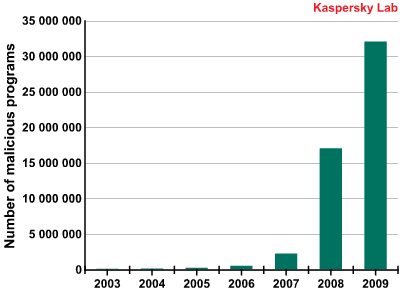

The statistics generated by different companies differ (some companies count the number of files, some count the number of signatures, and some the number of attacks), but everyone’s statistics reflect the precipitate growth in the number of malicious programs in 2008. While Kaspersky Lab identified around 2 million unique malicious programs over a period of 15 years (between 1992 and 2007), in the space of a single year (2008) the company identified more than 15 million unique pieces of malware.

In 2009, the number of malicious programs in the Kaspersky Lab collection reached 33.9 million.

Number of malicious programs in the Kaspersky Lab collection

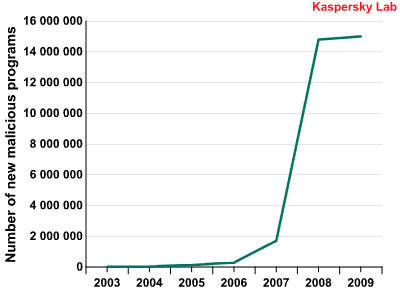

During the period 2007-2009 the number of new threats rose significantly. The response to this could only be an increase in the power of antivirus centres processing threats (and in-the-cloud antivirus technologies connected with this); the development of new automatic detection techniques; the implementation of new heuristic, virtualization and behaviour analysis methods. In other words, the reaction of the antivirus industry was to create new technologies designed to improve the quality of protection. It would be said that the industry experienced a technological revolution. A standard antivirus solution of the 1990s (scanner and monitor) still offered the requisite level of protection in 2006. However, by 2009 this protection was no longer grounded in reality, and had effectively been replaced by combination solutions – Internet Security products which integrated a wide range of technologies to offer defence in depth.

While in 2007-2008 the number of new threats increased exponentially, in 2009 almost the same number of new malicious programs was identified as in 2008: approximately15 million.

Number of new malicious programs identified per year

There were several reasons for this. The malware boom of 2008 was due not only to the rapid evolution of virus writing in China, but also due to the evolution in file-infecting technologies, which resulted in an increase in the number of unique malicious files. An amalgamation of attack vectors used, with a shift towards attacks on web browsers, also played a role.

All these trends were maintained in 2009, but the increase in the number of malicious programs slowed significantly. Moreover, there was a drop in Trojan activity, e.g. gaming Trojans. This was as we forecast at the end of the previous year, and this trend became clear in mid-2009.

Serious competition on this market, a drop in profits for cybercriminals, and the serious efforts made by antivirus companies all led to a drop in the number of gaming Trojans, and this was noticed in mid-2009 by other antivirus vendors.

One of the reasons for the drop in numbers was that gaming companies started addressing the problem of security, while at the same time many players started taking measures in order to protect themselves against such threats.

The successful measures taken by law enforcement and regulatory agencies, telecommunications companies and the antivirus industry against criminal Internet hosting companies and services also helped reduce the number of malicious programs. The first step was taken in 2008 when services such as McColo, Atrivo and EstDomains were closed. In 2009, further steps were taken, resulting in UkrTeleGroup, RealHost and 3FN being forced to cease their activity.

The companies mentioned above were notorious for offering services to all types of spammers and cybercriminals, including the provision of botnet command and control centers, phishing resources, sites with exploits, etc.

However, the closure of criminal hosting services has not put a conclusive stop to criminal and scammer activity, as cybercriminals have managed to find new resources. Nonetheless, during the period when such criminals were busy “moving house”, the Internet did become more secure.

At the moment, all the signs point to the trends detailed above being maintained in 2010, and the number of unique malicious programs created in 2010 will be commensurate with the figures for 2009.

The year in review

2009 was characterized by complex malicious programs with rootkit functionality; global epidemics; the Kido (Conficker) worm; web attacks and web botnets; SMS fraud and attacks on social networks.

Increased sophistication

In 2009, malicious programs became significantly more complex. For instance, whereas in the past the number of malware families with rootkit functionality could be counted in handfuls, in 2009 such programs not only became widespread but also markedly more sophisticated. Such threats which deserve a mention are Sinowal (the bootkit), TDSS and Clampi.

Kaspersky Lab analysts have been tracking the evolution of Sinowal for the last two years; spring 2009 brought the latest wave. This malware effectively masked its presence in the system, and the majority of antivirus programs were unable to detect it. At that point in time, the bootkit was the most advanced piece of malware. Moreover, Sinowal actively combated the efforts of antivirus companies to bring down the botnet’s command and control center.

In the main, the bootkit spread via compromised sites, portals offering pornographic material, and sites offering pirate software. Almost all servers which infected victim machines were part of so-called “affiliate programs”, in which site owners and malware authors work together. Such affiliate programs are very common in the Russian and Ukrainian cybercriminal world.

Another malicious program, TDSS, implemented two extremely complex technologies simultaneously: it infects Windows system drivers and creates its own virtual file system in which it hides its own (malicious) code. TDSS had no precedent, and was the first piece of malware able to penetrate the system at such a level.

Clampi came to the attention of security professionals in summer 2009, after a number of major American companies and authorities had been infected. This malware, which first appeared in 2008 (and which, according to some data, was of Russian origin) was designed to steal account data relating to certain online banking systems. The modification which appeared in 2009 differed from previous variants not only in terms of its sophisticated, multi-module structure (similar to that implemented in the notorious Zbot) but also in terms of the highly complex communication structure used in the botnet it created, which encrypted traffic using RSA. Another notable characteristic of Clampi was that it used standard Windows utilities when spreading via local networks. This caused a number of problems for certain antivirus solutions which were unable to block “allowlisted applications” and were therefore unable to combat the attack.

These threats were also notable for spreading widely across the Internet. Both Sinowal and Clampi reached global epidemic level, and TDSS caused one of the biggest epidemics of 2009. Packed.Win32.Tdss.z, which appeared in September, and which was called TDL 3 by its author, became especially widespread.

Epidemics

Last year, we forecast that the number of global epidemics would increase, and sadly, this forecast proved to be correct. Global epidemics were caused not only by the threats mentioned above, but by a whole range of other malicious programs.

Attacks on victim machines

Data collected by the Kaspersky Security Network shows that more than a million systems respectively were attacked by the malicious programs listed below:

- Kido – worm

- Sality – virus/worm

- Brontok – worm

- Mabezat – worm

- Parite.b – file virus

- Virut.ce – virus/bot

- Sohanad – worm

- TDSS.z – rootkit/backdoor

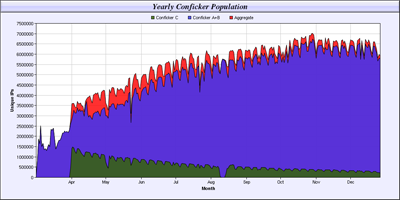

Unquestionably, the major epidemic of the year was caused by Kido (Conficker), which infected millions of machines around the world. The worm penetrated victim machines in several ways: by brute-forcing network passwords, via USB, and via the Windows MS08-067 vulnerability. Each infected machine then became part of the botnet. Combating the botnet was made more difficult by the fact that Kido implemented the very latest, most sophisticated virus writing techniques. For instance, one modification of the worm was designed to update itself from 500 domains; these domain addresses were randomly chosen from a list of 50,000 addresses which was generated daily. P2P-like connections were used as an additional update channel. Kido also prevented security solutions from being updated, disabled security services, and blocked access to antivirus vendor sites.

The creators of Kido remained relatively quiet until March 2009. However, we estimate that by that time they had managed to infect up to 5 million computers around the world. Although Kido didn’t spread via spam, and didn’t conduct DoS attacks, researchers expected this to start happening on 1 April, as the version of Kido which had started spreading in March was designed to start downloading additional modules at the beginning of April. However, the creators of Kido were playing a waiting game, and during the night of 8-9 April, a command was passed to infected machines to update the malware via P2P. In addition to Kido updates, victim machines downloaded two additional programs: a variant of Email-Worm.Win32.Iksmas, which sends spam, and a variant of FraudTool.Win32.SpywareProtect2009, a rogue antivirus program which demands payment in order to delete threats allegedly detected on the victim machine.

In order to combat such a widespread threat, the Conficker Working Group was created. This group united antivirus companies, Internet providers, independent research organizations, educational institutions and regulatory bodies. This group was the first example of serious international co-operation which went beyond the bounds of everyday communication between antivirus researchers, and it could act as the blueprint for how organizations around the world should interact in order to combat global threats.

The Kido (Conficker) epidemic lasted throughout 2009, and by November, the number of infected machines exceeded 7 million.

The Kido epidemic. Source: www.shadowserver.org

Given the experience of epidemics caused by other worms (Lovesan, Sasser, Slammer), it seems likely that Kido will continue to remain at epidemic level in 2010.

The epidemic caused by Virut should also be highlighted. Virus.Win32.Virut.ce is notable in that it targets web servers. Its infection methods also deserve a mention: it not only infects executable files with .EXE and .SCR extensions, it also appends specially crafted code to the end of files with .HTM, .PHP, and .ASP files in the form of a link, e.g. <iframe src=”http://ntkr(xxx).info/cr/?i=1″ width=1 height=1></ iframe>

When a user views a legitimate (infected) site, malicious content located on the link will be downloaded to the victim machine. The virus also spreads via P2P networks together with infected key generators and popular software distributions. The aim is to unite the infected computers in an IRC botnet which is used to send spam.

Infected web resources

One of the biggest infections on the Internet, which affected tens of thousands of resources, was caused by several waves of Gumblar infections. Initially, legitimate web pages were infected with a script. This script stealthily redirected requests to a cybercriminal site designed to spread malware.

The malware was called Gumblar after the malicious site used in the first attack to which users viewing compromised resources were redirected. This site then infected victim machines. These attacks were an excellent example of the way in which Malware 2.5 works (this topic was covered in the Kaspersky Security Bulletin: Malware Evolution 2008 at the beginning of last year).

In the autumn, the links which were placed on compromised sites no longer led to cybercriminal sites, but to legitimate, infected sites; this made combating the Gumblar epidemic significantly more difficult.

Why did Gumblar spread so quickly? The answer is simple: Gumblar is a fully automated system. Antivirus researchers are facing a new generation of self-building botnets. The system is cyclical in nature: those visiting compromised sites are actively attacked, and once these victim machines have been infected using Windows executable files, FTP account data is stolen. These FTP accounts are then used to infect all pages on new (previously uninfected) web servers. In this way the number of infected pages rises and, as a result, more and more computers become infected. The entire process is automated, and the owners of the system only have to update the Trojan executable which steals passwords, and the exploits used to conduct browser attacks.

Fraud

The frauds seen on the Internet are becoming more and more varied. Common or garden phishing attacks have now been joined by sites which offer access to a range of services in return for payment. (Of course, the services are never actually provided.) Russia is the leader in this area, and it’s Russian scammers who have created a wide range of sites offering “services” such as “locate someone via GSM”, “read private messages on social networking sites”, “collect information”, etc. In order to use such a “service”, the user needs to send an SMS to a premium pay number, although s/he is not told that the SMS can cost up to $10. Alternatively, the user is told to “subscribe”, again via SMS, and once such a subscription has been created, payment will be deducted daily from the mobile account.

Several hundred such “services” have been identified, and they are supported by dozens of affiliate programs. The “services” were promoted using traditional email spam, spam on social networks, and instant messaging spam. In order to conduct future spam runs, cybercriminals then used malware and phishing attacks designed to gain access to users’ accounts, created dozens of fake social networking sites, etc. It was only at the end of 2009 that mobile service providers, the administrators of social networks, and the antivirus virus industry started to combat this type of cybercriminal activity in an effective way.

As mentioned above, part of Kido’s payload is to download a rogue antivirus solution to victim machines. Rogue antivirus solutions are designed to persuade the user that there are threats present on his/her computer (although this is not, in fact, the case) and activate an “antivirus product” (which has to be paid for). The more accurately such rogue solutions copy genuine software, the better the chances are that the victim will pay up.

In 2009, rogue antivirus solutions were increasingly used by scammers and cybercriminals. Rogue software is not only spread using other malicious programs but also by Internet advertisements. At the moment, a large number of sites display banners promoting a new “wonder” product which will act as a cure-all. Even legitimate sites often display such flashing banners or insistent flash advertising for such “new antivirus” products, and it’s common to encounter pop-ups which offer the opportunity to download such solutions for free.

Rogue antivirus solutions first appeared, and then became widespread, due to the fact that they’re easy to develop, a mature distribution system already exists, and they can be used to make large profits in a short space of time. In November 2009, the FBI estimated that cybercriminals had used rogue AV solutions to earn approximately $150 million.

The Kaspersky Lab collection currently contains more than 300 rogue antivirus families.

Malware for alternative platforms and devices

In 2009, cybercriminals continued to examine the opportunities offered by alternative platforms such as Mac OS and mobile operating systems. Apple itself started to address the issue of malware targeting Mac by integrating an antivirus scanner in the latest version of its operating system – previously the company had asserted that malware posed no threat to Mac OS. However, in the area of mobile operating systems, the situation remains unclear. On the one hand, in 2009, long-predicted events came to pass: the first iPhone malware appeared in the form of the Ike worm, the first spyware targeting Android was created, and the first signed malware for Symbian smartphones was identified. On the other hand, the struggle for market share in the arena of mobile operating systems continues, and this means that virus writers are unable to concentrate their efforts on a single operating system.

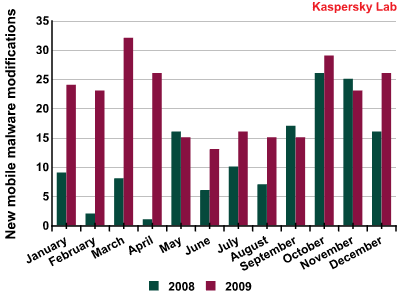

In 2009, 39 new mobile malware families and 257 new mobile malware variants were identified. This is in comparison to the 30 new families and 143 new modifications identified in 2008. The graph below gives a breakdown by month:

New mobile malware modifications by month (2008-2009 гг.)

The most striking events in mobile malware are covered in the article “ Mobile Malware Evolution: An Overview, Part 3“. It’s worth highlighting the following events and trends of 2009:

- mobile malware is now being used to make money

- the appearance of signed malware for Symbian S60 3rd edition

- a variety of SMS scams

- the appearance of malicious programs designed to make money which are capable of contacting remote cybercriminal servers

The appearance of malware able to contact remote servers was, perhaps, the most striking event of the second half of 2009 in terms of mobile malware. Such programs appeared due to the popularity of WiFi networks and the advent of cheap mobile Internet services: both these factors make it possible for mobile phone and smartphone owners to use the Internet more frequently than previously.

Malware which is able to contact remote servers opened up new horizons for cybercriminals.

- SMS Trojans which send SMS messages to premium pay numbers are able to get message parameters from the remote server. If a particular prefix is blocked, the cybercriminals do not have to use a different malicious program, but simply change the prefix on the server.

- Malware already installed on mobile devices can be updated from the remote server.

- Mobile malware which is able to connect to a remote server could be the first step towards the creation of botnets made up of infected mobile devices.

These trends are likely to continue in 2010, and the antivirus industry will be faced with a large number of malicious programs for mobile devices which will connect to the Internet in order to deliver their malicious payload.

The appearance of Backdoor.Win32.Skimer was a unique event in 2009. Although the incident provoked by this malware actually occurred at the end of 2008, it was only widely publicized in spring 2009. Skimer was the first malicious program targeting ATM machines. Once an ATM was infected using a special access card, criminals were able to perform a number of illegal actions: withdraw all the funds in the ATM, or get data from cards used in the ATM. The malware was clearly written by someone with excellent knowledge of ATM hardware and software. An analysis of the program resulted in the conclusion that the program was designed to target ATM machines in Russia and the Ukraine, as it tracks US dollar, Russian rouble, and Ukrainian hryvna transactions.

There are two ways in which the malicious code could have penetrated the ATM: either by physical access to the ATM system, or by gaining access via the bank’s internal network. A standard antivirus solution is able to combat such threats, and all banks are strongly recommended to conduct an antivirus scan of exploited ATM networks.

Forecast

In 2010 the following issues and events are likely to come to the fore:

There will be a shift in the attack vectors used, with a move away from the web to file-sharing networks. This is the latest step in the evolutionary chain: between 2000 and 2005 attacks were carried out via email; between 2005 and 2006 the main attack vector was the Internet; and between 2006 and 2009 attacks were carried out via web sites (including social networks). In 2009, mass epidemics were caused by malicious files being spread via torrent sites. It wasn’t only well-known threats such as TDSS and Virut which were spread in this way but also the first backdoors for Mac OS. In 2010, the number of incidents involving P2P networks is likely to increase significantly.

- The battle for traffic. Cybercriminals are making increasing efforts to legalize their business, and the Internet offers a multitude of opportunities to earn money by creating large volumes of targeted traffic. Such traffic can be created by using botnets. While at the moment it is openly criminal groupings involved in the battle for botnet traffic, it seems likely that “grey” services will appear in this market in the future. So-called “affiliate programs” provide botnet owners with the opportunity to realize their assets, even if criminal services such as spam, DoS attacks, or spreading malware are not being offered.

- Epidemics. As previously, the identification of vulnerabilities will be the major cause of epidemics, and this applies both to non-Microsoft software (Adobe, Apple) and the recently released Windows 7. It should be noted that third-party developers have recently started devoting more effort to identifying errors in their products. If no serious vulnerabilities are identified, in terms of security 2010 could be one of the quietest years in recent history.

- Malware will become ever more complex. At the moment there are threats in existence which use modern file-infecting techniques and rootkit functionality. Many antivirus solutions are unable to disinfect systems infected by such malware. On one hand, antivirus technologies will develop in such a way as to prevent threats from penetrating a system in the first place; on the other hand, the threats which are able to evade security solutions will be almost invulnerable.

- There will be a drop in the number of fake antivirus solutions, mirroring the decrease in the number of gaming Trojans. These programs which first appeared in 2007 reached a peak in 2009, and were linked to a number of major epidemics. The rogue antivirus market is now saturated, and the profits made by cybercriminals are negligible. With the antivirus industry and law enforcement agencies focussing their attention on such rogue solutions, it will be increasingly difficult for such programs to survive.

- Google Wave and attacks conducted via this service will undoubtedly be a hot topic in 2010. Such attacks are likely to evolve in a standard way, starting with spam, moving to phishing attacks, and then a shift to vulnerabilities being exploited and malware being spread. The release of ChromeOS is also a matter of great interest, but it’s unlikely that cybercriminals will focus their efforts on this platform in the coming year.

- 2010 is likely to be a difficult year for the iPhone and Android platforms. The appearance of the first threats targeting these platforms in 2009 demonstrates that cybercriminals are starting to examine these platforms and the opportunities they offer. While it is only jailbroken iPhones which are at risk, there are no such limitations in the case of Android, as applications from any source can be installed. The growing popularity of Android phones in China, and weak monitoring of published applications will lead to a number of serious virus incidents in 2010.

Kaspersky Security Bulletin 2009. Malware Evolution 2009