Overview

In the second quarter of 2011, we saw the further development of trends that we wrote about in our previous ‘Evolution of Malware’ reports; these include an increase in the number of malicious programs targeting mobile platforms and their distribution via app stores, plus targeted attacks against companies and popular Internet services. However, there were also some surprises that we will examine later on in this report.

Fake antivirus products: another round

The return of the phonies

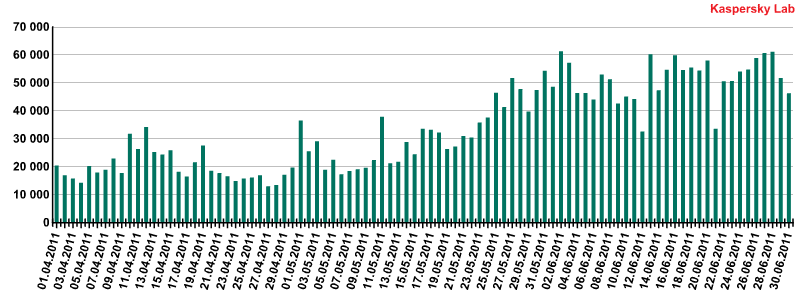

In 2010 we noted a decline in the number of players in the fake antivirus market, and as a result, fewer counterfeit programs used to distribute fake antivirus products. This remained the case for a relatively long period of time. However, during the second quarter of 2011, the number of fake antivirus programs detected globally by Kaspersky Lab began to increase. Furthermore, the number of users whose computers blocked attempts to install counterfeit software increased 300% in just three months. This burgeoning wave of fake antivirus programs began in March of this year and the number of attacks continues to rise.

The daily number of fake antivirus program detections (Q2 2011)

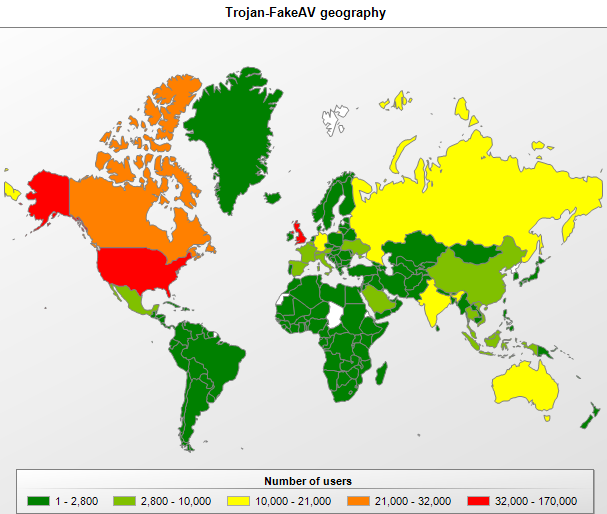

Unlike the year 2009 when malicious users tried to infect computers around the world with fake antivirus programs, today’s cybercriminals are focused on targeting users in developed countries such as the US, Great Britain and Canada.

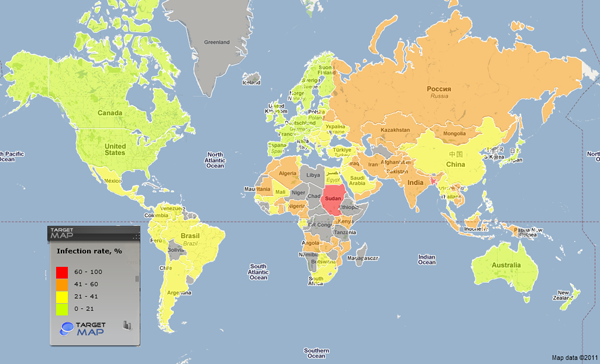

Fake antivirus attacks by location in Q2 2011

This is related to the technological evolution of this type of malicious program.

The evolution of FakeAV: Trojans targeting Macs

The first fake antivirus program targeting Mac OS X appeared back in 2008 and no new fake antivirus programs targeting Mac appeared for a long time thereafter. However, in the second quarter of 2011, antivirus analysts detected several “products” almost simultaneously, with names like MacDefender, MacSecurity, MacProtector, etc. These were obviously released by the same people in order to generate illegal revenue by luring unwary Mac OS X users into their scam.

The cybercriminals obviously decided that FakeAV was the key to their expansion into the emergent malware market for OS X as it is relatively easy to dupe unwary users with these types of malicious programs.

In order to force users to install the fake antivirus program, scammers used authentic-looking websites offering computer malware scanning services. Using black SEO, links to these websites were planted at the top of Google Image search results for the search queries that were the most popular at the time. A user looking for something like “Osama bin Laden dead photos” would be led to a website offering to scan their computer. After the fake scan, the user would see a message that the scan had detected numerous security issues, followed by an offer to install a ‘free’ antivirus product. If the user agreed to the installation, they would be asked to enter their administrator password. After the fake antivirus was installed, the program would work just like the fake antivirus programs targeting Windows: it would ‘detect’ thousands of nonexistent threats and offer to fix the computer. Incidentally, the declared number of threats allegedly detected by these fake antivirus programs was several times greater than the actual number of known malicious programs targeting Mac systems. The so-called treatment required users to purchase the full version of the program for anywhere between US $50 and $100. Note that in these cases, by purchasing the product with their credit cards, users were also providing the cybercriminals with a full set of credit card details that the cybercriminals could then use to charge users whatever they wished.

On 31 May 2011, one month after the first new fake antivirus program for Mac was detected, Apple issued a security patch for Xprotect, the built-in security system for OS X. This new patch makes it possible to automatically delete fake antivirus programs. However, just a few hours after the new patch, the malicious users released a new version of their program which Xprotect was unable to detect for the next 24 hours. This rapid penetration of security was due to the fact that Xprotect uses a signature scanner, a low-technology method of detecting malicious programs. This means that all malicious users have to do is change a few bytes in their program code in order to bypass security. Shortly thereafter, in order to get around Xprotect more efficiently the virus writers added a small downloader to their infection process. This is detected by Kaspersky Lab’s products as Trojan-Downloader.OSX.FavDonw. Why is this attack so effective? Because Xprotect only scans files that were downloaded from the Internet via a browser, so if a file is downloaded by a fake antivirus program it is not subjected to scanning. As a result, malicious users can easily get around the built-in protection by regularly updating the downloader and making small changes to the main file from time to time. Furthermore, this attack process does not require users to enter any passwords when installing the malicious program.

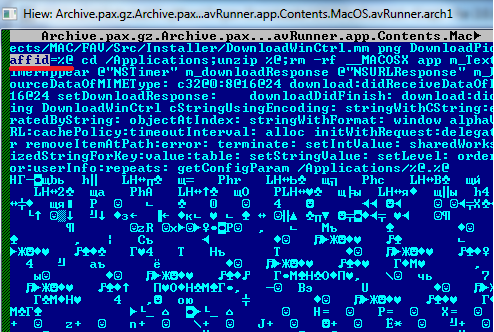

Just like the FakeAV programs targeting Windows, the fake antivirus programs for Mac OS are spread using the infamous affiliate program arrangement. This is obvious from the “affid” string in the downloader’s files which is an abbreviated form of ‘affiliate ID’. By using this parameter, the affiliate program owners know which of their affiliates are owed payment for a particular malware installation.

A section of code from the fake antivirus downloader

targeting OS X (Trojan-Downloader.OSX.FavDonw)

As the number of Mac OS X users is highest in developed countries, the cybercriminals realize that they will maximize their earnings by spreading their FakeAVs in these regions. Thus the geographical distribution of fake antivirus programs targeting Mac OS X coincides with the geographical distribution of the same types of programs targeting Windows.

The next step in the evolution of malicious programs targeting Mac OS X is likely to be the emergence of universal rookit downloaders for the Mac platform, as well as Trojans such as ZeuS and SpyEye designed to steal banking information. Mac users are advised to seriously consider the security of their systems and install an antivirus solution.

Mobile Trojans: the attack continues

The DroidDream family’s new addition

In late May, the official Android Market was again infiltrated by malicious programs. Just like in the first quarter of the year, these were predominantly repackaged versions of legitimate software to which Trojan modules had been added. A total of 34 malicious packets were detected. The Trojan that came with the packet was in fact a new variant of the familiar DroidDream (Backdoor.AndroidOS.Rooter). In order to get the Trojan onto Android Market its functions were altered slightly. The exploit that helps the Trojan gain administrator rights — previously the telltale feature of this particular program — was removed from the bundle and later downloaded onto the infected phone by the Trojan.

The KunFu Backdoor

The second major threat targeting the Android operating system, and one which has made much progress during Q2 2011, is a backdoor detected by Kaspersky Lab’s products as Backdoor.AndroidOS.KunFu. The Trojan works in the traditional manner by connecting to a server, the name of which is written into the body of the program. After installing the Trojan using the known “Rage against the cage” exploit, the Trojan acquires administrator rights. Next it collects information about the infected device and sends it to the cybercriminals, and then it waits to receive commands from the server. This malicious program can be installed without the user being aware, and will download app bundles and visit websites. The Trojan is mainly spread via unofficial app stores and primarily targets Chinese users — the control servers have been found to use hosting services based in China.

The author of this malicious program is very interested in the viability of this Trojan and goes to great lengths to avoid the Trojan being detected by antivirus products. Over the course of three months, more than 29 different variants of this program were found. Furthermore, the exploit code used to expand rights was encrypted using a DES algorithm. The most recent versions of the Trojan have been altered again: the registry containing key functions was rewritten into Native code from Java in an attempt to make it more difficult to analyze.

Worrying statistics

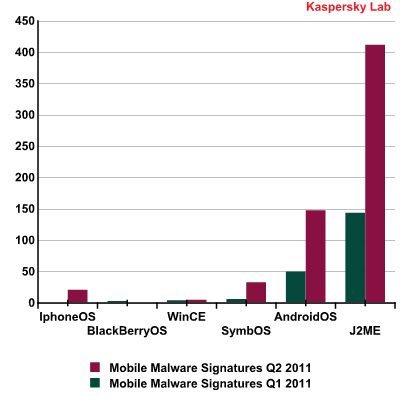

Kaspersky Lab’s statistics show that the number of mobile threats targeting different mobile platforms continues to increase exponentially.

The number of new signatures for mobile threats

targeting a variety of platforms, Q1 & Q2 2011

The number of detected threats (malicious software for phones and entry-level smartphones) running on J2ME doubled during Q2 2011, while the number of detections of malicious programs targeting Android nearly tripled.

The current monetization scheme used by most mobile Trojans involves sending text messages to short numbers. The result is withdrawals of funds from users’ accounts or the implementation of subscriptions to fee-based services without the individual user’s consent. In the latter case, which is more common in Asia, a user will receive a text message from a service with information about the subscription. To prevent the user from noticing anything suspicious, the Trojan will delete the message about the fee-based service as soon as it arrives. As a result, the Trojan can continue to operate on a device for a long time, making money for the malicious user all the while.

What is worrying is the fact that malicious programs designed for mobile devices are being spread not only through a variety of resources belonging to third parties, but also via official app stores. Clearly, Android Market needs to review its app publication policy. At this point, however, the owners of both official and unofficial stores are in no hurry to change any of their rules — and this failure to take action is playing right into the hands of malicious users. In this situation, the number of those who want to make money at the expense of the average user will grow, which will impact the number of threats, as well as the quality of those threats. This means that there is just one course of action open to the average user: install an antivirus product on their mobile device if they have not already done so. Otherwise, the chances increase that they will not be the only person using their phone.

Reputation at risk

The second quarter of 2011 turned out to be even more eventful than the first quarter in terms of the hacking of major companies. The latest list of victims includes Sony, Honda, Fox News, Epsilon and Citibank, and in most cases, client data was compromised.

The personal data of large numbers of users is not only of interest to some legitimate commercial organizations but also to the cybercriminals in order to launch various, typically targeted, attacks. Furthermore, from what we know, the hackers did not use the stolen data for commercial purposes. There is no information about the sale of such data on the black market or any use thereof by cybercriminals. This behavior on the part of hackers leads us to believe that a get-rich-quick scheme was actually not the driving force behind these attacks.

The second quarter of this year will be remembered by many because of one of the largest leaks of personal data resulting from the hack of the PlayStation Network and Sony Online Entertainment, both Sony companies. According to Sony’s own estimates, malicious users were able to get their hands on the data of up to 77 million users of PSN and Quriocity services (see: republicans.energycommerce.house.gov [PDF 5,47 Мб]). For several weeks, these Sony services were unavailable worldwide while an investigation was conducted into the incidents. This naturally caused resentment among the company’s clients, and when the services resumed, clients were asked to restore their accounts by using the very same personal information that was potentially stolen in the attack. Notably, no users reported any incidents when restoring their accounts.

In addition to personal user data, similar services also store data about the credit cards clients used to pay for services. After Sony was hacked, underground forums began discussing rumors about how the hackers may have also stolen secret CVV2 codes, which are required to complete online transactions. However, the company announced that the hackers would only have been able to obtain the card numbers and expiry dates, not the CVV2 codes. Again, there have not been any reports indicating the sale or abuse of this data.

Today, there is no data in the public domain about who was behind this attack or what their motives were. This indicates that the main objective of the hackers was not to earn a quick buck, but to damage the Sony Corporation’s reputation. Based on information available in the link below, after a second round of problems with PSN, British vendors of games and consoles saw an upsurge in the number of returns and exchanges of Sony products. A solid reputation takes years to build — but just hours to destroy. (See: http://news.cnet.com/8301-13506_3-20062596-17.html.)

Hacktivists

A wave of “hacktivism” — hacking or bringing down systems in protest against the actions of governments or large corporations — is continuing to gain momentum. In the first quarter of this year we saw the emergence of a new group called LulzSec which over the course of 50 days succeeded in hacking a number of systems and publishing the personal information of tens of thousands of users.

Just like in the case of the now familiar Anonymous group, LulzSec was not motivated by money. Representatives of the group confirmed that they had hacked corporate services “for the Lulz”. Furthermore, in contrast to Anonymous, this new group is a more active user of social media, including Twitter, in order to report its actions to the world.

LulzSec successfully hacked major corporations such as Sony, EA, AOL and government agencies, including the US Senate, the CIA, SOCA UK and others. The information that LulzSec obtained from their attacks was published on their website and later made available via a torrent network. More often than not, the publications included personal data.

It would be useful to know how the group was able to penetrate these protected systems. Many attacks could have been completed using known mechanisms for automated search vulnerabilities, including SQL injections. After gaining access to the data stored on less protected servers, such as a login or hash password, the hackers could have used them for subsequent hacks, as even people with network administration rights often use the same password for a variety of services.

Over time, the LulzSec attacks began to take on political overtones. LulzSec pooled its efforts with Anonymous in order to launch a number of attacks against government agencies and large corporations with the intention of publishing any classified data they acquired. As a result of the series of attacks dubbed “AntiSec”, hackers were able to gain access to, among other things, data belonging to the Arizona state police authorities. Correspondence originating from the police department was made public, in addition to classified documents and the personal information and passwords of certain police department members. The representatives of the hacking groups involved announced that they had launched this attack in protest against Arizona’s introduction of more stringent immigration policies. One statement read: “We are targeting AZDPS specifically because we are against SB1070 and the racial-profiling anti-immigrant police state that is Arizona.”

Naturally, all of these attacks drew the attention of law enforcement agencies across the globe. In Spain, three people were arrested on suspicion of their involvement in attacks organized by Anonymous, and another 32 were arrested in Turkey. By the end of June 2011, LulzSec announced that it was disbanding. The investigation launched in several countries around the world in order to identify and arrest the groups’ members could have been one reason for LulzSec’s demise.

The actions taken to disclose personal data by so-called hacktivists are, unfortunately, predominantly immoral and irresponsible. The disclosure of data that at first glance appears unrelated to money could still have substantial and untoward implications, including of a financial nature. Firstly, many users — despite warnings from IT security professionals — use the same password to access many different services, including online banking. Secondly, the publication of data could interest criminals in the offline world, which is when “the Lulz” stop. Incidentally, the members of the group were determined to maintain their anonymity. It’s perhaps a little ironic that people who do not want to disclose their own identity demand the disclosure of information from others.

The attacks against government organizations will no doubt continue even after the official breakup of LulzSec. The sysadmins of large companies and government organizations will need to remain alert and test their systems regularly, or face the risk of falling victim to the next wave of ‘hacktivism.’

Cybercrime and the law

Shutdown of the Coreflood botnet

In April 2011, yet another botnet was shut down: Coreflood. Under a court ruling, the US Department of Justice and the FBI gained access to five control servers, which then allowed them to take control of the botnet. The botnet was built up using the Backdoor.Win32.Afcore program, and according to information from the FBI, contained 2 million zombie computers at the time it was shut down.

Shutting down a botnet is a complicated process, not only from the technical side, but also from a legal standpoint. After taking control of Coreflood, law enforcement agency personnel were able to delete all of the bots on infected computers with a click of a mouse. However, that kind of action could violate the laws of other countries as the bot infection was not limited to the US. That is why the locations of the infected computers were first determined based on their IP addresses. American law enforcement agencies then obtained consent to delete bots from those organizations with infected computers before seeking permission from the courts for the remote deletion of the malicious programs. In the end, the CoreFlood botnet lost most of its resources. However, just as with Rustock, until the real owners of the botnet are found it is always possible that they may return to their underground business and build a new botnet.

Shutting down decentralized botnets like Kido, Hlux and Palevo could turn out to be even more complicated than closing down a botnet like Coreflood, Rustock or Bredolab. Shutting down these types of botnets can only be achieved by launching botnet control interception procedures. Essentially, this will mean modifying malicious programs on users’ computers located in different countries around the world. There is, however, currently no legislation that would allow law enforcement agencies and security professionals to take the kinds of actions that would be necessary.

We hope that law enforcement agencies will continue to shut down botnets and that the relevant authorities in different countries will be able to pool their resources in order to create the conditions needed to rid the world of computer malware.

Legislation in Japan

As practice has shown, the most effective means of fighting computer crime is arresting the virus writers. On 17 June, 2011, the Japanese parliament passed legislation introducing punitive measures for the creation and storage of malware.

Before this law was passed, Japan lacked the means to punish people for creating malware. Virus writers had to be indicted on other counts such as violation of copyright, piracy or property damage etc., which was highly ineffective and thus the law needed to be amended.

Under the new legislation, Internet service providers will be required to store logs for two months and submit them to law enforcement agencies if requested.

Japan has taken a major step forward in the fight against cybercrime.

Virtual currency and real problems

In 2009 the programmer and mathematician Satosi Nakamoto began an interesting project to create a cryptocurrency known as bitcoin. There are a few important aspects about the concept of this currency. Bitcoin is not associated with any centralized entity or regulator, the money is generated on users’ computers that have launched a special program and all money transfers within the bitcoin system are anonymous. Today, bitcoin is actively used to pay for a variety of goods and services online. There are exchanges where you can swap your e-currency for actual currency, including dollars, pounds, yen etc. It is important to bear in mind that cybercriminals are fond of this currency too. For example, LulzSec accepted donations in bitcoins and some underground forums accept cryptocurrency in payment for malicious programs.

Virtual wallets

The growing popularity of bitcoin is a magnet to those who seek to acquire money by illegal means. Encrypted wallets containing money can be stored on users’ computers and access can be gained to these wallets by entering the right password. Malicious users typically steal the wallets first and then try to determine the passwords afterwards. In late June, IT security professionals detected a relatively simple Trojan that sent bitcoin wallets to malicious users when launched. It is not known whether or not the owner of the malicious program was able to hack the wallets, but if the Trojan is improved, it could pose a very real threat to users of cryptocurrency. Furthermore, considering the trend of using bots to steal all kinds of information from computers, this function could become a component of malicious programs designed to track computer activity on targeted machines.

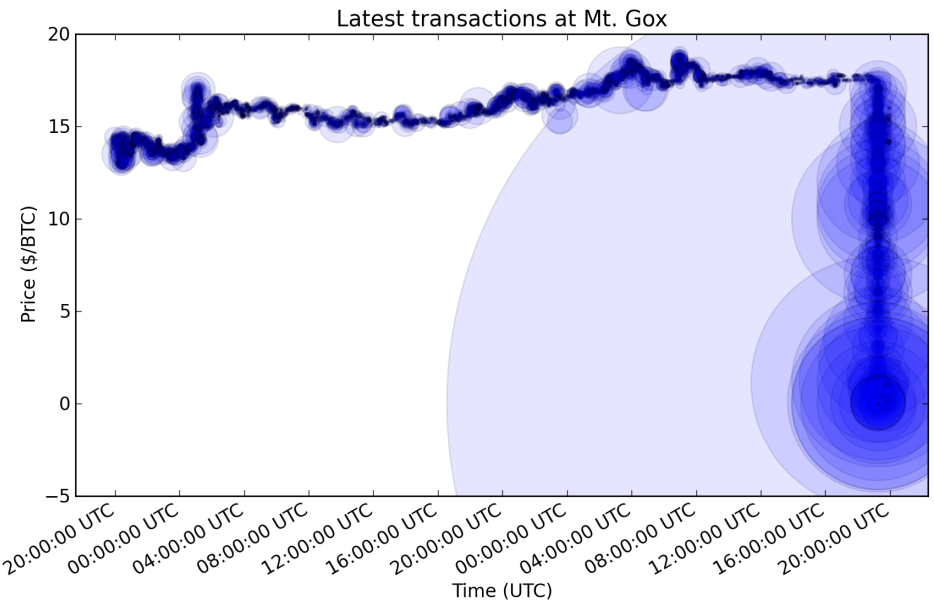

Collapse of the bitcoin market

The bitcoin economy suffered an unpleasant blow in the second quarter of 2011 when its exchange rate plummeted on Mt. Gox, one of the most commonly used exchanges. Over the course of just a few minutes, the rate fell from US $16 to just a few cents. The reason behind the drop was the sale of a hacked account holding a huge amount of bitcoins at a very low price. After discovering the sharp drop in the exchange rate, the exchange’s administrators quickly took the decision to suspend trading and all suspicious transactions were voided.

The bitcoin collapse of 20 June, 2011

It later came to light that the account in question was hacked as the result of a leaked database of logins, electronic addresses and hash passwords belonging to the exchange’s users. Clearly, a malicious user gained access to the passwords and orchestrated the exchange rate crash with the intention of getting rich quick. Prior to the Mt. Gox incident, a Cross Site Request Forgery-type vulnerability was detected that allowed malicious users to send specialized requests which misled users and forced them into engaging in a bitcoin transaction. These incidents have proven beyond a doubt that transactions with virtual cash should always involve extensive security. This is why financial institutions devote so much attention to security and the world of e-money should clearly do the same.

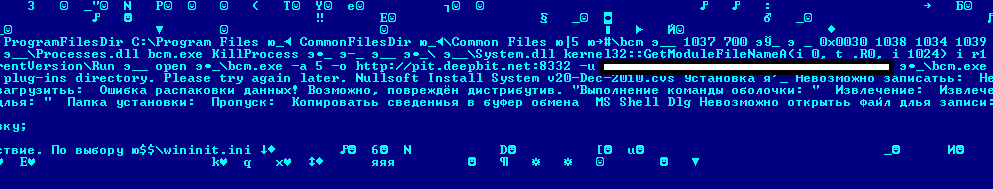

Bitcoin mining, Russian style: Trojan.NSIS.Miner.a

At present, only 1 million of the planned 21 million bitcoins have been generated. Anyone can participate in generating the currency, or ‘bitcoin mining’ as it is known, and earn compensation in the form of the generated bitcoins.

As we can see from code strings, some Russian-speaking cybercriminals have decided that stealing virtual wallets and hacking their passwords is just not cost efficient, while forcing unsuspecting users to engage in bitcoin mining is a novel idea. In late June, Kaspersky Lab discovered a malicious program comprised of a legitimate bitcoin mining program (bcm) and controlled by a Trojan module. After the Trojan is launched, the infected computer begins to generate bitcoins for the malicious users. This Trojan is found in Russia (37%), India (12%), Ukraine (7%), Kazakhstan (5%), and Vietnam (3%). Happily, the scam was discovered relatively early on by the automatic bitcoin pool, resulting in the malicious user’s account in the bitcoin mining system being first blocked, then deleted.

Part of Trojan.NSIS.Miner.a’s code indicating where to transfer generated bitcoins

It is important to note that the viability of the entire bitcoin cryptocurrency system depends on user confidence and an absence of “counterfeit” coins. Unfortunately, the incidents described above show that malicious users are actively attempting to find a loophole in the bitcoin economy’s security systems. The administrators of the bitcoin exchange and pool need to concentrate their efforts on protecting their system and upholding their business reputation, as their entire enterprise could collapse if user confidence in the bitcoin system disintegrates.

Statistics

Below, we will review some statistics recorded by the various anti-malware modules in Kaspersky Lab products that are installed on users’ computers around the globe. All the statistical data used in this report has been obtained with the help of consenting participants of the Kaspersky Security Network (KSN). The global exchange of information regarding malware activities involves millions of Kaspersky Lab’s product users from 213 countries around the world.

Online threats

The statistical data cited in this section was recorded by the Web Anti-Virus module in Kaspersky Lab products which is designed to protect users against downloading malicious code from infected web pages. Infected sites include those specifically created by cybercriminals, websites with content created by users, such as forums, and other legitimate websites that have been compromised.

Objects detected on the Internet

In the second quarter of 2011, the number of blocked attacks stood at 208,707,447 – these attacks were carried out from web resources located in different countries all over the world. A total of 112,474 different malicious and potentially unwanted programs were detected in these incidents.

The Top 20 malicious objects detected on the Internet

| Ranking | Name* | Percentage of all attacks** |

| 1 | Blocked | 65.44% |

| 2 | Exploit.Script.Generic | 21.20% |

| 3 | Trojan.Script.Iframer | 15.13% |

| 4 | Trojan.Win32.Generic | 7.70% |

| 5 | Trojan-Downloader.Script.Generic | 7.66% |

| 6 | Trojan.Script.Generic | 7.57% |

| 7 | AdWare.Win32.FunWeb.kd | 4.37% |

| 8 | AdWare.Win32.FunWeb.jp | 3.08% |

| 9 | Hoax.Win32.ArchSMS.heur | 3.03% |

| 10 | Trojan-Downloader.JS.Agent.fxq | 2.51% |

| 11 | Trojan.JS.Popupper.aw | 2.18% |

| 12 | Trojan.HTML.Iframe.dl | 1.76% |

| 13 | Trojan-Downloader.Win32.Generic | 1.62% |

| 14 | AdWare.Win32.HotBar.dh | 1.49% |

| 15 | Worm.Script.Generic | 1.30% |

| 16 | Exploit.JS.CVE-2010-1885.k | 1.20% |

| 17 | Hoax.Win32.ArchSMS.pxm | 1.04% |

| 18 | Trojan.JS.Redirector.pz | 0.87% |

| 19 | Trojan.JS.Agent.bun | 0.85% |

| 20 | Hoax.Win32.Screensaver.b | 0.84% |

* Detected verdicts returned by the Web Anti-Virus module. The information is provided by users of Kaspersky Lab products who have consented to share their local statistical data.

** Percentage of all web attacks detected on computers of unique users.

Top place in the ranking is occupied by various malicious URLs (65.44%) which are on our denylist – addresses of web pages serving exploit kits, bots, ransomware Trojans, etc.

Half of the malicious programs that make up the Top 20 are used in drive-by attacks in one way or another. These include script downloaders, redirectors and exploits. Cybercriminals increasingly focus on evading the various tools that analyze malicious code written in script languages such as JS and VBS, etc. They use techniques such as hiding a script’s main functionality in parts of the HTML code where analyzers least expect them to be. As a result, most of the malware created in this manner is heuristically detected as generic.

Second place in the Top 20 is occupied by the verdict Exploit.Script.Generic. This has unseated the Trojan downloaders that occupied first or second positions in the ranking for three years. A variety of script exploits, which account for a fifth of all recorded online attacks, are detected under this name. This shows that the number of drive-by attacks which use exploits continues to grow, while attacks that involve users downloading and launching malicious files are on the decline.

Six of the Top 20 places are taken up by adware or hoaxes. Samples of the FunWeb adware family appear at 7th and 8th positions, based on the frequency of detection. The installation of such malware was most often blocked on computers in the US (25.2%) and India (32.7%). Hoax programs such as Hoax.Win32.ArchSMS, which are paid installers of free programs, have taken two positions in the ranking, 17th and 20th.

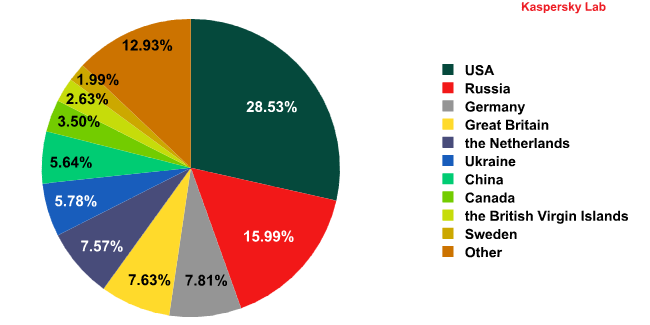

Malware hosting countries

In the second quarter of 2011, 10 countries hosted 87% of the web resources used to distribute malware. This is two percentage points less than in the previous quarter. The geographical location of each attack source was determined by comparing the domain name to the actual IP address of the domain and identifying the geographical location of the IP address (GEOIP).

The distribution of countries with malware-hosting web resources in Q2 2011

The development of legislation and successes in combating cybercrime in the US and western Europe may result in hosting sites used to distribute malware gradually moving from developed to developing countries. The Netherlands leads the field in reducing the number of malicious hosting sites: compared to the previous quarter, its share has fallen by 4.3 percentage points to 7.57%. The efforts of the Dutch police, including those aimed at neutralizing botnets such as Bredolab and Rustock, are scaring cybercriminals away from hosting malware in the country.

China is also seeing a decline in the number of malicious hosting sites: the country’s share has gone down by another two percentage points, reaching 5.6%. While two years ago Chinese hosting sites were the primary source of malware on the web, they are now gradually disappearing from the antivirus radar.

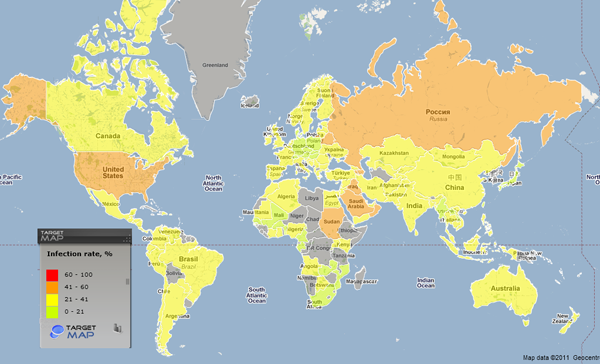

Countries where users run the highest risk of web infection

To evaluate the risk of users’ computers being infected via the web in various countries of the world, we analyzed how often web antivirus modules detected a malicious program on users’ machines in each country.

The Top 10 countries in which users’ computers run the highest risk of infection via the web

| Position | Country* | % of individual users** |

| 1 | Oman | 55.7% |

| 2 | Russian Federation | 49.5% |

| 3 | Iraq | 46.4% |

| 4 | Azerbaijan | 43.6% |

| 5 | Armenia | 43.6% |

| 6 | Sudan | 43.4% |

| 7 | Saudi Arabia | 42.6% |

| 8 | Belarus | 41.8% |

| 9 | USA | 40.2% |

| 10 | Kuwait | 40.2% |

*Countries in which the number of users of Kaspersky Lab products is below the threshold of 10 thousand were not included in the calculations.

**The number of individual users’ computers that were attacked via the web as a percentage of the total number of users of Kaspersky Lab’s products in the country.

Apart from the US, the Top 10 ranking includes countries falling into two distinct categories. The first category includes the former Soviet republics. In these countries, various fraudulent programs prevail, including malware such as Hoax.Win32.ArchSMS that sends text messages to premium-rate numbers, thereby making money for the cybercriminals.

The second category comprises countries from the Middle East including Iraq, Sudan, Oman, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. The highest risk of infection was registered in Oman, where half of all the computers monitored were attacked during the quarter.

All of the countries can be divided into groups according to the risk of infection.

- High-risk countries. This group, with risk levels ranging from 41% to 60%, includes eight out of the 10 countries making up the Top 10: Oman, Russia, Iraq, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Sudan, Saudi Arabia and Belarus.

- Average-risk countries. This group, with risk levels ranging from 21% to 41%, comprises 94 countries, including the US (40.2%), China (34.8%), the UK (34.6%), Brazil (29.6%), Peru (28.4%), Spain (27.4%), Italy (26.5%), France (26.1%), Sweden (25.3%) and the Netherlands (22.3%).

- Safe-surfing countries. In the second quarter of 2011, this group comprised 28 countries with risk levels ranging from 11.4% up to 21%, including Switzerland (20.9%), Poland (20.2%), Singapore (19.6%) and Germany (19.1%).

Risk of computer infection while surfing the web by country

The high-risk group has changed compared to the first quarter of 2011: Kazakhstan (-1 percentage point) left the group while Sudan (+4.5 percentage points) and Saudi Arabia (+2.6 percentage points) joined it.

It is particularly noteworthy that the US, at 40.2%, is very close to joining the high-risk group of countries. This is primarily due to the increase in the number of FakeAV detections that we mentioned in the first part of the report. The overall growth in the number of rogue antivirus detections is largely due to the quantity detected in the United States. In addition, cybercriminals in America try to infect as many computers as possible with bot clients belonging to the TDSS and Gbot networks. Websites used to distribute FakeAV programs in this region rank second and sixth based on the frequency of malware download attempts.

The average-risk group included eight countries more in the second quarter than it did in the first quarter. All parts of the world are represented in this group.

The group of safe-surfing countries has decreased by five. One of the countries that left the group was Finland (22.1%), which moved to the average-risk group.

The lowest percentages of users attacked while surfing the web are in Japan (13%), Taiwan (13.7%), the Czech Republic (16.1%), Denmark (16.2%), Luxembourg (16.9%), Slovenia (17.8%) and Slovakia (18.3%).

Local threats

All statistics quoted in this section were recorded by the on-access scanner inside Kaspersky Lab’s products.

Malicious objects detected on users’ computers

During Q2 2011, Kaspersky Lab’s solutions successfully blocked 413,694,165 attempted local infections of users’ computers connected to the Kaspersky Security Network.

In total, there were 462,754 incidences of malicious and potentially unwanted programs reported. This number includes, among others, objects that entered the victim computers via local networks or removable storage media rather than through the web, email or network ports.

As we can see, the number of unique objects is three orders of magnitude smaller than that of attempted infections. This means that malware development is controlled by a small group of people.

The Top 20 malicious objects detected on users’ computers

| Position | Name* | % of individual users** |

| 1 | DangerousObject.Multi.Generic | 35.93% |

| 2 | Trojan.Win32.Generic | 23.02% |

| 3 | Net-Worm.Win32.Kido.ir | 13.48% |

| 4 | Virus.Win32.Sality.aa | 5.92% |

| 5 | AdWare.Win32.FunWeb.kd | 4.99% |

| 6 | Net-Worm.Win32.Kido.ih | 4.57% |

| 7 | Virus.Win32.Sality.bh | 4.44% |

| 8 | Trojan.Win32.Starter.yy | 4.43% |

| 9 | Hoax.Win32.ArchSMS.heur | 3.91% |

| 10 | Worm.Win32.Generic | 3.65% |

| 11 | Trojan-Downloader.Win32.Geral.cnh | 2.62% |

| 12 | Virus.Win32.Sality.ag | 2.45% |

| 13 | HackTool.Win32.Kiser.zv | 2.29% |

| 14 | Hoax.Win32.ArchSMS.pxm | 2.22% |

| 15 | HackTool.Win32.Kiser.il | 2.19% |

| 16 | Worm.Win32.FlyStudio.cu | 2.09% |

| 17 | Trojan.JS.Agent.bhr | 2.03% |

| 18 | Virus.Win32.Nimnul.a | 2.02% |

| 19 | Hoax.Win32.Screensaver.b | 1.95% |

| 20 | Trojan-Downloader.Win32.VB.eql | 1.81% |

* These statistics are compiled from the malware detection verdicts given by the antivirus modules of users of Kaspersky Lab products who have agreed to submit their statistical data.

** The number of individual users on whose computers the antivirus module detected these objects as a percentage of all individual users of Kaspersky Lab products on whose computers a malicious program was detected.

First place in the ranking is occupied by various malicious programs detected with the help of cloud-based technologies. These detection technologies work when a malicious program first enters circulation and the antivirus databases do not have signatures or heuristic tools to detect it; at this time, information about this malware may exist in the cloud. In such cases, the malicious program is named as DangerousObject.Multi.Generic.

Ten of the Top 20 programs contain a self-propagating mechanism or are used as components in worm distribution schemes.

In the second quarter of 2011 we saw an explosion in the number of infections caused by a new malicious program, Virus.Win32.Nimnul.a. This program spreads using two methods – one being the infection of executable files and the other via removable storage media using the autoplay function. It is distributed primarily in Asian countries such as Indonesia (20.7%), India (20%) and Vietnam (16.6%), where operating systems are rarely patched and antivirus software is installed far less often. Its main payload is Backdoor.Win32.IRCNite.yb – a backdoor which connects to a remote server and adds the computer to a zombie network.

The Top 20 features only two families of infectious malware – Sality and Nimnul. The development of these types of malicious programs is time-consuming and requires an excellent knowledge of operating systems and file formats, etc. At the same time, the distribution of such malware usually comes to the attention of antivirus vendors fairly rapidly. Consequently, infectors are now used by only a handful of virus writers or criminal groups and the use of infectious malware may decline further in the near future. It is likely that the use of sophisticated infectors will be limited to targeted attacks, where 100% effectiveness is crucial and customers are prepared to pay for the development of complex malware.

Countries in which users’ computers ran the highest risk of local infection

We have calculated the percentage of KSN users in different countries on whose computers attempted local infections were blocked. The resulting numbers show the average share of infected computers in a specific country.

The Top10 countries in which infected computers are located

| Position | Country* | % of individual users’ computers infected ** |

| 1 | Bangladesh | 63.6% |

| 2 | Sudan | 61.0% |

| 3 | Iraq | 55.5% |

| 4 | Nepal | 55.0% |

| 5 | Angola | 54.4% |

| 6 | Tanzania | 52.6% |

| 7 | Afghanistan | 52.1% |

| 8 | India | 51.7% |

| 9 | Rwanda | 51.6% |

| 10 | Mongolia | 51.1% |

* Countries in which the number of users of Kaspersky Lab products is below the threshold of 10 thousand were not included in the calculations

** The number of individual users on whose computers local threats were blocked as a percentage of all Kaspersky Lab product users in the country.

There was one curious difference between Q2 and Q1 of 2011 in the Top 10 countries in which users’ computers ran the highest risk of local infection. In Q2, the Top 10 included India, where every second computer ran the risk of local infection at least once in the past three months. Over the last few years, India has been growing steadily more attractive to cybercriminals as the number of computers in the country increases steadily. Other factors that attract cybercriminals include a low overall level of computer literacy and the prevalence of pirated software that is never patched. As for the types of malware attempting to penetrate users’ machines, most of it is designed for building botnets. There are numerous self-propagating malicious programs, such as Virus.Win32.Sality, Virus.Win32.Nimnul and IM-Worm.Win32.Sohanad. There are also many variants of autorun worms and Trojans. In the first quarter, Microsoft released a patch that blocks the autoplay function on removable storage media. However, the patch is automatically installed only on those systems that have Windows Update enabled, not a very common practice in India. Botnet controllers obviously see India as a place with millions of unprotected and unpatched computers which can remain active on zombie networks for extended periods of time.

All the countries of the world can be divided into groups based on their local infection levels:

- Maximum level of local infection. This group, with infection levels exceeding 60%, includes Bangladesh (63.6%) and Sudan (61%).

- High level of local infection. This group, with infection levels ranging from 41% to 60%, includes 36 countries from across the globe, such as India (51.7%), Indonesia (48.4%), Kazakhstan (43.8%), Russia (42.2%),

- Medium level of infection. This group comprises 58 countries with local infection levels ranging from 21% up to 41% and includes Ukraine (38.4%), the Philippines (37.1%), Thailand (35.7%), China (35.3%), Turkey (32.9%), Ecuador (31.1%), Brazil (30%) and Argentina (27.3)

- Lowest level of infection: Comprising 34 countries across the globe.

The risk of local computer infections in different countries

During the second quarter of 2011, the number of countries with high levels of infection decreased by 12, the number of countries with medium levels of infection increased by two and the number of those with the lowest levels of infection increased by 10.

Several European countries have moved to the group with the lowest levels of infection: Greece (19.9%), Spain (19.4%), Italy (19.3%), Portugal (18.6%), Slovakia (18.2%), Poland (18.1%), Slovenia (17.2%) and France (14.7%). The main reason for the decline in the number of attempted infections in these countries is a significant reduction in the number of incidents involving autorun worms due to the patching of Windows, the prevalent operating system in the region. Notice that Slovakia and Slovenia are in the group of safe-surfing countries.

The Top 5 countries that are safest in terms of the level of local infections are:

| Position | Country | % of individual users |

| 1 | Japan | 8.2% |

| 2 | Germany | 9.4% |

| 3 | Denmark | 9.7% |

| 4 | Luxembourg | 10% |

| 5 | Switzerland | 10.3% |

Vulnerabilities

The second quarter of 2011 saw 27,289,171 vulnerable applications and files detected on users’ computers. We detected an average of 12 different vulnerabilities on each computer.

The Top 10 vulnerabilities detected on users’ computers are shown in the table below.

IT Threat Evolution: Q2 2011