Any user data — from passwords for entertainment services to electronic copies of documents — is highly prized by intruders. The reason is simply that almost any information can be monetized. For instance, stolen data can be used to transfer funds to cybercriminal accounts, order goods or services, and, if the desire or opportunity is lacking to do it oneself, it can always be sold on to other cybercrooks.

This thirst for stolen data is confirmed by the statistics: in the first half of 2019, more than 940,000 users were attacked by malware designed to harvest a variety of data on the computers. For comparison, in the same period of 2018, slightly less than 600,000 users of Kaspersky products were attacked. The threat’s called “Stealer Trojans” or Password Stealing Ware (PSW), a type of malware designed to steal passwords, files, and other data from victim computers.

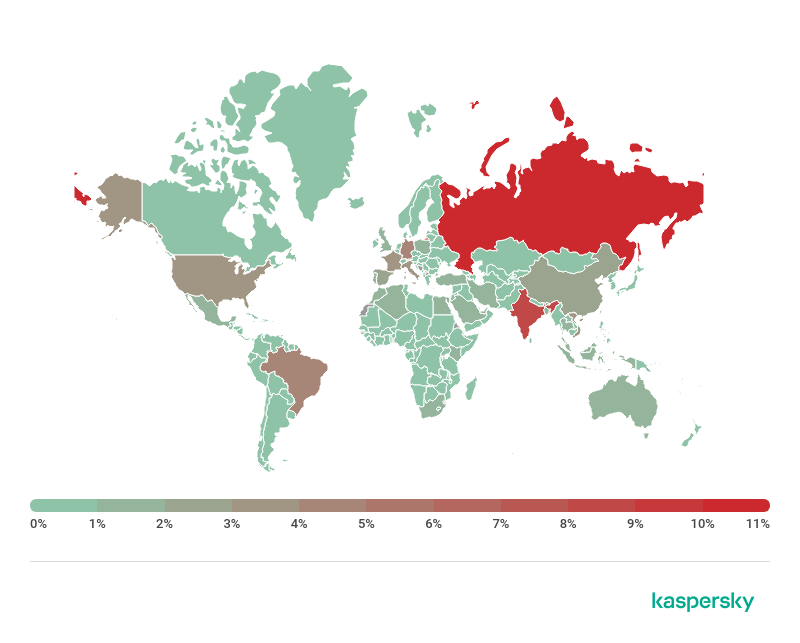

Geographical distribution of users attacked by Stealer Trojans, H1 2019

Over the past six months, we have detected such malware most often among users in Russia, Germany, India, Brazil, United States and Italy.

What’s being stolen?

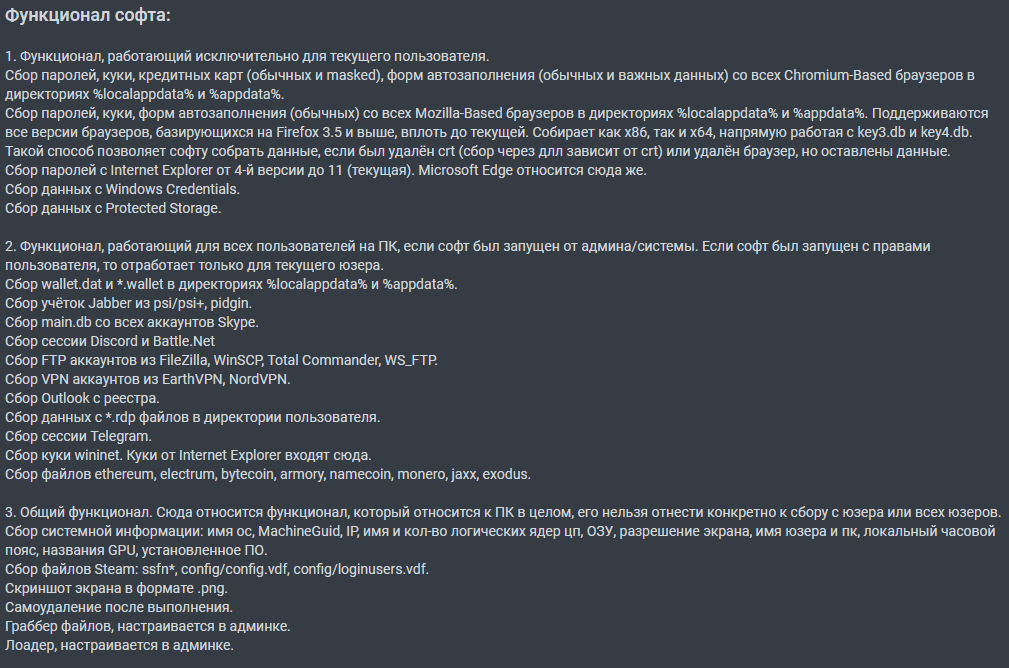

Such stealers are commonly touted on malware seller/buyer forums. Each vendor advertises their product as the most effective and multifunctional, describing a wide spectrum of its capabilities.

Based on our analysis of this threat, an average stealer can:

- Collect data from browsers:

- Passwords

- Autofill data

- Payment cards

- Cookies

- Copy files:

- All files from a specific directory (such as Desktop)

- Files with a specific extension (TXT, DOCX)

- Files for specific apps (cryptocurrency wallets, messenger session files)

- Forward system data:

- Operating system version

- User name

- IP address

- And much more

- Steal accounts from various applications (FTP clients, VPN, RDP, and others)

- Take screenshots

- Download files from the Internet

The most multifunctional specimens (for example, Azorult) take a complete “image” of the victim’s computer and data:

- Full system information (list of installed programs, running processes, user/computer name, system version)

- Hardware specification (video card, CPU, monitor)

- Saved passwords, payment cards, cookies, browsing history for almost all known browsers (more than 30)

- Passwords for mail/FTP/IM clients

- Instant messenger files (Skype, Telegram)

- Steam game client files

- Files for more than 30 cryptocurrency programs

- Screenshots

- Files specified by “mask” (for example, the mask %USERPROFILE%\Desktop\ *.txt,*.jpg,*.png,*.zip,*.rar,*.doc means that all files with the specified extensions from the victim’s desktop are to be sent to the malware operator).

Let’s take a closer look at this last point. Why collect text files or, even more curiously, all files on the desktop? The fact is that files most needed by the user are commonly stored there. And among them may well be a text file containing frequently used passwords. Or, for example, work documents containing the confidential data of the victim’s employer.

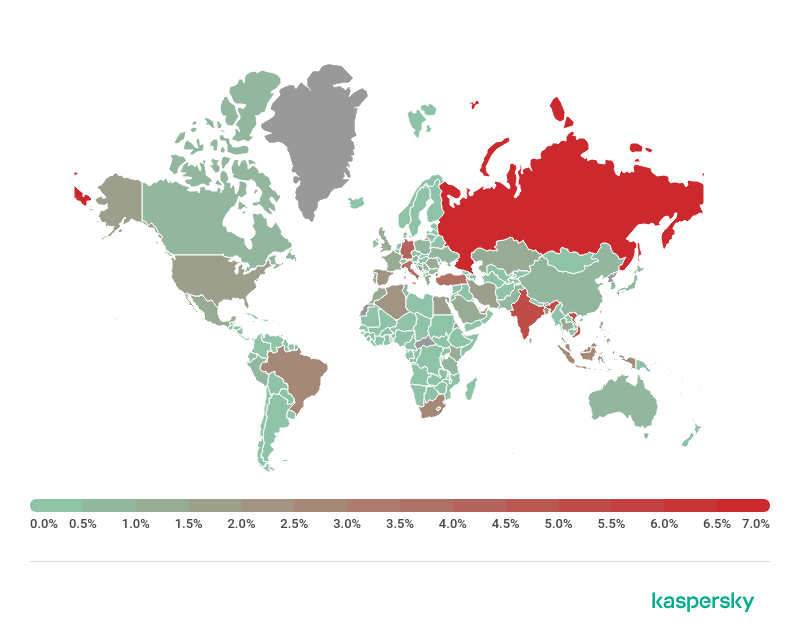

Geographical distribution of users attacked by Trojan-PSW.Win32.Azorult, H1 2019

The above-listed features helped turn Azorult into one of the most widely spread Stealer Trojans, detected on the computers of more than 25% of all users who encountered Trojan-PSW type malware.

After buying (or creating) the malware, the cybercriminals set about distributing it. Most often, this is done by sending emails with malicious attachments (for example, office docs with malicious macros that in turn download the Trojan). In addition, stealers can be distributed through botnets when the latter receive a command to download and run a particular Stealer Trojan.

How passwords get stolen from browsers

When it comes to stealing browser data (passwords, bank card details, autofill data), all stealers act in much the same way.

Google Chrome and Chromium-based browsers

In browsers based on the Chromium open source code, saved passwords are protected by DPAPI (Data Protection API). The browser’s own storage is used for this purpose, implemented as an SQLite database. Only the OS user who created the passwords can retrieve them from the database, and only on the computer on which they were encrypted. This is ensured by the particular encryption implementation, whereby the encryption key includes information about the computer and system user in a certain form. This data is not available to regular users outside the browser without special utilities.

But all this is no obstacle to a stealer that has already penetrated the computer, as it runs with the above-mentioned OS user rights; in this case, the process of extracting all saved data in the browser is as follows:

- Retrieval of the database file. Chromium-based browsers store this file at a standard and unchangeable path. In order to avoid problems with access (for example, if the browser happens to be using it), stealers can copy the file to another location or terminate all browser processes.

- Reading of encrypted data. As already mentioned, browsers use an SQLite database from which data can be read using standard tools.

- Decryption of data. As per the data protection principle described above, stealing the database file itself does not help get hold the data, since decryption must take place on the user’s computer. But that’s not a problem, because the decryption is performed directly on the victim’s computer through a call to the CryptUnprotectData function. The cybercriminals need no additional data — DPAPI does everything itself, since the call was made on behalf of the system user. As a result, the function returns passwords in “clean” readable form.

That’s it! Saved passwords, bank card details, and browsing history are all retrieved and ready to be sent to the cybercriminal server.

Firefox and browsers based on it

Password encryption in Firefox-based browsers is slightly different to that in Chromium, but for the stealer the process of obtaining them is just as simple.

In Firefox browsers, encryption uses Network Security Services — a set of libraries from Mozilla for the development of secure apps — and among others, the nss3.dll library.

As with Chromium-based browsers, retrieving data from the encrypted storage comes down to the same simple actions, but with some provisos:

- Retrieval of the database file. Firefox-derived browsers, unlike ones based on Chromium, generate a random user profile name that makes the location of the file with encrypted data unknowable beforehand. However, since the intruders know the path to the folders with user profiles, it is not difficult for them to sort through them to check for a file with a certain name (the name of the file with encrypted data for its part does not depend on the user and is always the same). Moreover, this data can remain even if the user deleted the browser, a fact exploited by some stealers (e.g. KPOT).

- Reading of encrypted data. The data can be stored either as in Chromium (in SQLite format), or in the form of a JSON file with fields containing encrypted data.

- Decryption of data. To decrypt the data, the stealer has to load the nss3.dll library, and then call several functions and get the decrypted data in readable form. Some stealers have functions for working directly with browser files, which allows them to be independent of this library and operate even if the browser has been uninstalled. However, it should be noted that if the data protection function is used with a master password, decryption without knowing (or bruteforcing) this password is impossible. Unfortunately, this feature is disabled by default, and enabling it requires a deep rummage in the settings menu.

Again that’s it! The data is ready to be forwarded to the cybercriminals.

Internet Explorer and Microsoft Edge

In Internet Explorer versions 4.x — 6.0, saved passwords and autofill data were stored in the so-called Protected Storage. To retrieve them (not only IE data, but also that of other apps using this storage), the stealer needed to load the pstorec.dll library and get all the data in open form by way of simple listing.

Internet Explorer 7 and 8 use a slightly different approach: The storage used is called Credential Store, and encryption is performed using a salt. Unfortunately, this salt is identical and well known, so the stealer can get all the saved passwords again by calling the same CryptUnprotectData function as above.

Internet Explorer 9 and Microsoft Edge use a new type of storage called Vault. However, it promises nothing new in terms of data acquisition: the stealer loads vaultcli.dll, calls several functions from it, and retrieves all the saved data.

So even a series of changes to the data storage method does not prevent data from being read by stealers.

Some facts

Code borrowing/reuse

In analyzing specimens of new stealer families actively advertised by virus writers on specialized forums, we repeatedly came across code we had seen before in specimens of other families. This may be because some stealers have a common developer, who finished one project and used it as the basis for another one. For instance, the same person is behind Arkei and Nocturnal, as their sellers point out.

Another reason for this similarity could be code borrowing. The Arkei source code was sold by its author on these same forums, and may have become the basis for another stealer, Vidar. These Trojans have much in common, from data harvesting techniques and the format of received commands to the structure of data sent to the C&C center.

Narrow expertise required

Despite the abundance of multifunctional stealers, Trojans designed to steal specific information enjoy a certain demand. For example, the malware Trojan-PSW.MSIL.Cordis is tasked solely with stealing data from sessions in Discord, an IM popular with gamers. The source code of this Trojan is extremely simple, and consists in searching for and sending a single file to the C&C center.

Such Trojans are often not sold, but presented in the form of source codes for anyone to compile; therefore they are relatively common.

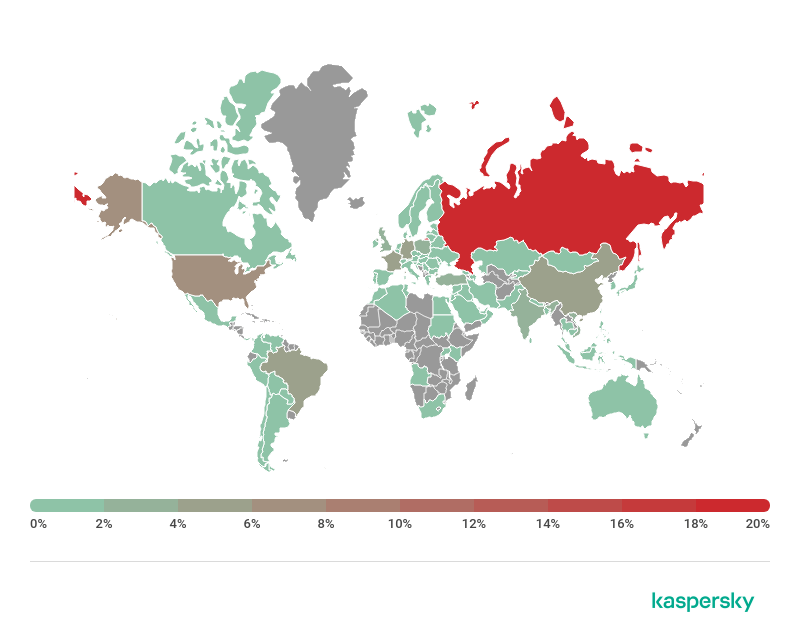

Geographical distribution of users attacked by Trojan-PSW.MSIL.Cordis, H1 2019

Using different programming languages

Although most known Stealer Trojans are written in the popular C/C++/C# languages, there are some specimens written in less common languages like Golang. One such Trojan is detected by Kaspersky products as Trojan-PSW.Win32.Gox. It can steal saved passwords, payment card details in Chromium-based browsers, cryptocurrency program files, and Telegram files.

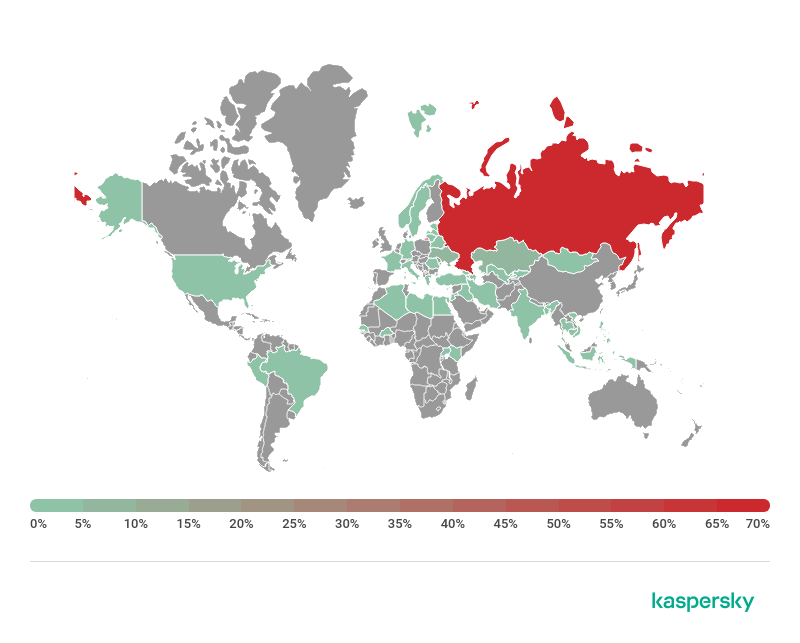

Geographical distribution of users attacked by Trojan-PSW.Win32.Gox, H1 2019

Conclusion

Users often entrust all critical data to the browser. After all, it’s convenient when passwords and bank card details are autofilled in the required fields. But we recommend against entrusting such vital information to browsers, since the methods of protection they use are no obstacle to malware.

The popularity of malicious programs hungry for browser data is showing no sign of slowing. Today’s crop of Stealer Trojans are actively supported, updated, and supplemented with new features (for example, the ability to steal 2FA data from apps that generate one-time access codes).

We recommend using special software for storing online account passwords and bank card details, or security solutions with appropriate technologies. Do not download or run suspicious files, do not follow links in suspicious emails, and generally observe all security precautions.

How to steal a million (of your data)

Alex

Just wander if the described relevant only for desktop computers or smartphones are affected too.