Analysis of data harvested by Kaspersky Lab’s IoT honeytraps

There were a number of incidents in 2016 that triggered increased interest in the security of so-called IoT or ‘smart’ devices. They included, among others, the record-breaking DDoS attacks against the French hosting provider OVH and the US DNS provider Dyn. These attacks are known to have been launched with the help of a massive botnet made up of routers, IP cameras, printers and other devices.

Last year the world also learned of a colossal botnet made up of nearly five million routers. The German telecoms giant Deutsche Telekom also encountered router hacking after the devices used by the operator’s clients became infected with Mirai. The hacking didn’t stop at network hardware: security problems were also detected in smart Miele dishwashers and AGA stoves. The ‘icing on the cake’ was the BrickerBot worm that didn’t just infect vulnerable devices like most of its ‘peers’ but actually rendered them fully inoperable.

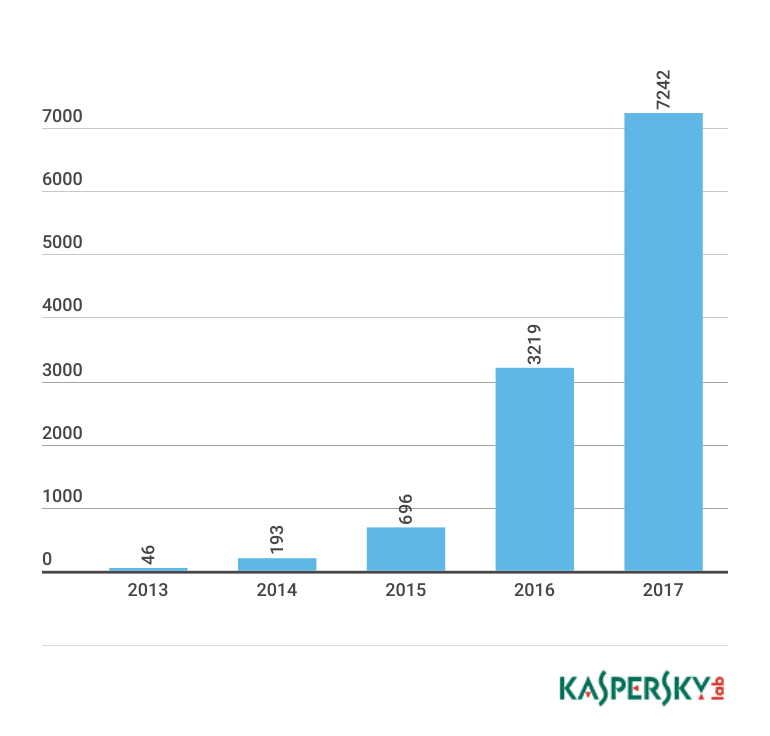

According to Gartner, there are currently over 6 billion IoT devices on the planet. Such a huge number of potentially vulnerable gadgets could not possibly go unnoticed by cybercriminals. As of May 2017, Kaspersky Lab’s collections included several thousand different malware samples for IoT devices, about half of which were detected in 2017.

The number of IoT malware samples detected each year (2013 – 2017)

Threat to the end user

If there is an IoT device on your home network that is poorly configured or contains vulnerabilities, it could cause some serious problems. The most common scenario is your device ending up as part of a botnet. This scenario is perhaps the most innocuous for its owner; the other scenarios are more dangerous. For example, your home network devices could be used to perform illegal activities, or a cybercriminal who has gained access to an IoT device could spy on and later blackmail its owner – we have already heard of such things happening. Ultimately, the infected device can be simply broken, though this is by no means the worst thing that can happen.

The main problems of smart devices

Firmware

In the best-case scenario, device manufacturers are slow to release firmware updates for smart devices. In the worst case, firmware doesn’t get updated at all, and many devices don’t even have the ability to install firmware updates.

Software on devices may contain errors that cybercriminals can exploit. For example, the Trojan PNScan (Trojan.Linux.PNScan) attempted to hack routers by exploiting one of the following vulnerabilities:

- CVE-2014-9727 for attacking Fritz!Box routers;

- A vulnerability in HNAP (Home Network Administration Protocol) and the vulnerability CVE-2013-2678 for attacking Linksys routers;

- ShellShock (CVE-2014-6271).

If any of these worked, PNScan infected the device with the Tsunami backdoor.

The Persirai Trojan exploited a vulnerability present in over 1000 different models of IP cameras. When successful, it could run arbitrary code on the device with super-user privileges.

There’s yet another security loophole related to the implementation of the TR-069 protocol. This protocol is designed for the operator to remotely manage devices, and is based on SOAP which, in turn, uses the XML format to communicate commands. A vulnerability was detected within the command parser. This infection mechanism was used in some versions of the Mirai Trojan, as well as in Hajime. This was how Deutsche Telekom devices were infected.

Passwords, telnet and SSH

Another problem is preconfigured passwords set by the manufacturer. They can be the same not just for one model but for a manufacturer’s entire product range. Furthermore, this situation has existed for so long that the login/password combinations can easily be found on the Internet – something that cybercriminals actively exploit. Another factor that makes the cybercriminal’s work easier is that many IoT devices have their telnet and/or SSH ports available to the outside world.

For instance, here is a list of login/password combinations that one version of the Gafgyt Trojan (Backdoor.Linux.Gafgyt) uses:

| root | root |

| root | – |

| telnet | telnet |

| !root | – |

| support | support |

| supervisor | zyad1234 |

| root | antslq |

| root | guest12345 |

| root | tini |

| root | letacla |

| root | Support1234 |

Statistics

We set up several honeypots (traps) that imitated various devices running Linux, and left them connected to the Internet to see what happened to them ‘in the wild’. The result was not long in coming: after just a few seconds we saw the first attempted connections to the open telnet port. Over a 24-hour period there were tens of thousands of attempted connections from unique IP addresses.

Number of attempted attacks on honeypots from unique IP addresses. January-April 2017.

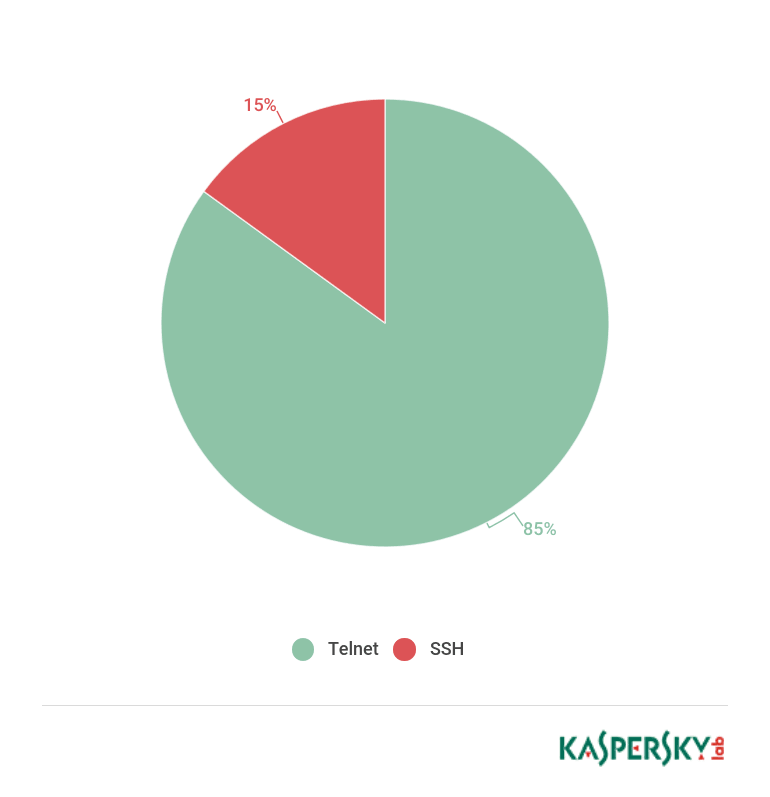

In most cases, the attempted connections used the telnet protocol; the rest used SSH.

Distribution of attempted attacks by type of connection port used. January-April 2017

Below is a list of the most popular login/password combinations that malware programs use when attempting to connect to a telnet port:

| User | Password |

| root | xc3511 |

| root | vizxv |

| admin | admin |

| root | admin |

| root | xmhdipc |

| root | 123456 |

| root | 888888 |

| root | 54321 |

| support | support |

| root | default |

| root | root |

| admin | password |

| root | anko |

| root | |

| root | juantech |

| admin | smcadmin |

| root | 1111 |

| root | 12345 |

| root | pass |

| admin | admin1234 |

Here is the list used for SSH attacks. As we can see, it is slightly different.

| User | Password |

| admin | default |

| admin | admin |

| support | support |

| admin | 1111 |

| admin | |

| user | user |

| Administrator | admin |

| admin | root |

| root | root |

| root | admin |

| ubnt | ubnt |

| admin | 12345 |

| test | test |

| admin | <Any pass> |

| admin | anypass |

| administrator | |

| admin | 1234 |

| root | password |

| root | 123456 |

Now, let’s look at the types of devices from which the attacks originated. Over 63% of them could be identified as DVR services or IP cameras, while about 16% were different types of network devices and routers from all the major manufacturers. 1% were Wi-Fi repeaters and other network hardware, TV tuners, Voice over IP devices, Tor exit nodes, printers and ‘smart-home’ devices. About 20% of devices could not be identified unequivocally.

Distribution of attack sources by device type. January-April 2017

Most of the IP addresses from which attempted connections arrived at our honeypots respond to HTTP requests. Typically, there are several devices using each IP address (NAT technology is used). The device responding to the HTTP request is not always the device that attacked our honeypot, though that is usually the case.

The response to such a request was a web page – a device control panel, some form of monitoring, or maybe a video from a camera. With this returned page, it is possible to try and identify the type of device. Below is a list of the most frequent headers for the web pages returned by the attacking devices:

| HTTP Title | Device % |

| NETSurveillance WEB | 17.40% |

| DVR Components Download | 10.53% |

| WEB SERVICE | 7.51% |

| main page | 2.47% |

| IVSWeb 2.0 – Welcome | 2.21% |

| ZXHN H208N V2.5 | 2.04% |

| Web Client | 1.46% |

| RouterOS router configuration page | 1.14% |

| NETSuveillance WEB | 0.98% |

| Technicolor | 0.77% |

| Administration Console | 0.77% |

| MГіdem – Inicio de sesiГіn | 0.67% |

| NEUTRON | 0.58% |

| Open Webif | 0.49% |

| hd client | 0.48% |

| Login Incorrect | 0.44% |

| iGate GW040 GPON ONT | 0.44% |

| CPPLUS DVR – Web View | 0.38% |

| WebCam | 0.36% |

| GPON Home Gateway | 0.34% |

We only see a portion of the attacking devices at our honeypots. If we need an estimate of how many devices there are globally of the same type, dedicated search services like Shodan or ZoomEye can help out. They scan IP ranges for supported services, poll them and index the results. We took some of the most frequent headers from IP cameras, DVRs and routers, and searched for them in ZoomEye. The results were impressive: millions of devices were found that potentially could be (and most probably are) infected with malware.

Numbers of IP addresses of potentially vulnerable devices: IP cameras and DVRs.

| HTTP Title | Devices |

| WEB SERVICE | 2 785 956 |

| NETSurveillance WEB | 1 621 648 |

| dvrdvs | 1 569 801 |

| DVR Components Download | 1 210 111 |

| NetDvrV3 | 239 217 |

| IVSWeb | 55 382 |

| Total | 7 482 115 |

Numbers of IP addresses of potentially vulnerable devices: routers

| HTTP Title | Devices |

| Eltex NTP | 2 653 |

| RouterOS router | 2 124 857 |

| GPON Home Gateway | 1 574 074 |

| TL-WR841N | 149 491 |

| ZXHN H208N | 79 045 |

| TD-W8968 | 29 310 |

| iGate GW040 GPON ONT | 29 174 |

| Total | 3 988 604 |

Also noteworthy is the fact that our honeytraps not only recorded attacks coming from network hardware classed as home devices but also enterprise-class hardware.

Even more disturbing is the fact that among all the IP addresses from which attacks originated there were some that hosted monitoring and/or device management systems with enterprise and security links, such as:

- Point-of-sale devices at stores, restaurants and filling stations

- Digital TV broadcasting systems

- Physical security and access control systems

- Environmental monitoring devices

- Monitoring at a seismic station in Bangkok

- Industry-grade programmable microcontrollers

- Power management systems

We cannot confirm that it is namely these types of devices that are infected. However, we have seen attacks on our honeypots arriving from the IP addresses used by these devices, which means at least one or more devices were infected on the network where they reside.

Geography of infected devices

If we look at the geographic distribution of the devices with the IP addresses that we saw attacking our honeypots, we see the following:

Breakdown of attacking device IP addresses by country. January-April 2017

As we mentioned above, most of the infected devices are IP cameras and DVRs. Many of them are widespread in China and Vietnam, as well as in Russia, Brazil, Turkey and other countries.

Geographical distribution of server IP addresses from which malware is downloaded to devices

So far in 2017, we have recorded over 2 million hacking attempts and more than 11,000 unique IP addresses from which malware for IoT devices was downloaded.

Here is the breakdown by country of these IP addresses (Top 10):

| Country | Unique IPs |

| Vietnam | 2136 |

| Taiwan, Province of China | 1356 |

| Brazil | 1124 |

| Turkey | 696 |

| Korea, Republic of | 620 |

| India | 504 |

| United States | 429 |

| Russian Federation | 373 |

| China | 361 |

| Romania | 283 |

If we rank the countries by the number of downloads, the picture changes:

| Country | Downloads |

| Thailand | 580267 |

| Hong Kong | 367524 |

| Korea, Republic of | 339648 |

| Netherlands | 271654 |

| United States | 168224 |

| Seychelles | 148322 |

| France | 68648 |

| Honduras | 36988 |

| Italy | 20272 |

| United Kingdom | 16279 |

We believe that this difference is due to the presence in some of these countries of bulletproof servers, meaning it’s much faster and easier to spread malware than it is to infect IoT devices.

Distribution of attack activity by days of the week

When analyzing the activities of IoT botnets, we looked at certain parameters of their operations. We found that there are certain days of the week when there are surges in malicious activity (such as scanning, password attacks, and attempted connections).

Distribution of attack activity by days of the week. April 2017

It appears Monday is a difficult day for cybercriminals too. We couldn’t find any other explanation for this peculiar behavior.

Conclusion

The growing number of malware programs targeting IoT devices and related security incidents demonstrates how serious the problem of smart device security is. 2016 has shown that these threats are not just conceptual but are in fact very real. The existing competition in the DDoS market drives cybercriminals to look for new resources to launch increasingly powerful attacks. The Mirai botnet has shown that smart devices can be harnessed for this purpose – already today, there are billions of these devices globally, and by 2020 their number will grow to 20-50 billion devices, according to predictions by analysts at different companies.

In conclusion, we offer some recommendations that may help safeguard your devices from infection:

- Do not allow access to your device from outside of your local network, unless you specifically need it to use your device;

- Disable all network services that you don’t need to use your device;

- If the device has a preconfigured or default password and you cannot change it, or a preconfigured account that you cannot deactivate, then disable the network services where they are used, or disable access to them from outside the local network.

- Before you start using your device, change the default password and set a new strong password;

- Regularly update your device’s firmware to the latest version (when such updates are available).

If you follow these simple recommendations, you’ll protect yourself from a large portion of existing IoT malware.

Honeypots and the Internet of Things

ISOGeek

As I am aware of Japan has also adopted IoT devices, while I do not have figures but definitely numbers would be more than Turkey, Romania, Vietnam or India. I am wondering why Japan is not included here. Is it because Kaspersky did not get stats from Japan or Japanese are more versatile in enforcing security ?

Gary Medel

People all over the world use IoT devices and they must be aware of the fact that the knowledge about internet things are useful.

Hereby the article follows the steps to process it and is helpful to us.