The concept of a smart city involves bringing together various modern technologies and solutions that can ensure comfortable and convenient provision of services to people, public safety, efficient consumption of resources, etc. However, something that often goes under the radar of enthusiasts championing the smart city concept is the security of smart city components themselves. The truth is that a smart city’s infrastructure develops faster than security tools do, leaving ample room for the activities of both curious researchers and cybercriminals.

Smart Terminals Have Their Weak Points Too

Parking payment terminals, bicycle rental spots and mobile device recharge stations are abundant in the parks and streets of modern cities. At airports and passenger stations, there are self-service ticket machines and information kiosks. In movie theaters, there are ticket sale terminals. In clinics and public offices, there are queue management terminals. Even some paid public toilets now have payment terminals built into them, though not very often.

Ticket terminals in a movie theater

However, the more sophisticated the device, the higher the probability that it has vulnerabilities and/or configuration flaws. The probability that smart city component devices will one day be targeted by cybercriminals is far from zero. Сybercriminals can potentially exploit these devices for their ulterior purposes, and the scenarios of such exploitation come from the characteristics of such devices.

- Many such devices are installed in public places

- They are available 24/7

- They have the same configuration across devices of the same type

- They have a high user trust level

- They process user data, including personal and financial information

- They are connected to each other, and may have access to other local area networks

- They typically have an Internet connection

Increasingly often, we see news on another electronic road sign getting hacked and displaying a “Zombies ahead” or similar message, or news about vulnerabilities detected in traffic light management or traffic control systems. However, this is just the tip of the iceberg; smart city infrastructure is not limited to traffic lights and road signs.

We decided to analyze some smart city components:

- Touch-screen payment kiosks (tickets, parking etc.)

- Infotainment terminals in taxis

- Information terminals at airports and railway terminals

- Road infrastructure components: speed cameras, traffic routers

Smart City Terminals

From a technical standpoint, nearly all payment and service terminals – irrespective of their purpose – are ordinary PCs equipped with touch screens. The main difference is that they have a ‘kiosk’ mode – an interactive graphical shell that blocks the user from accessing the regular operating system functions, leaving only a limited set of features that are needed to perform the terminal’s functions. But this is theory. In practice, as our field research has shown, most terminals do not have reliable protection preventing the user from exiting the kiosk mode and gaining access to the operating system’s functions.

Exiting the kiosk mode

Techniques for Exiting the Kiosk Mode

There are several types of vulnerabilities that affect a large proportion of terminals. As a consequence, there are existing attack methods that target them.

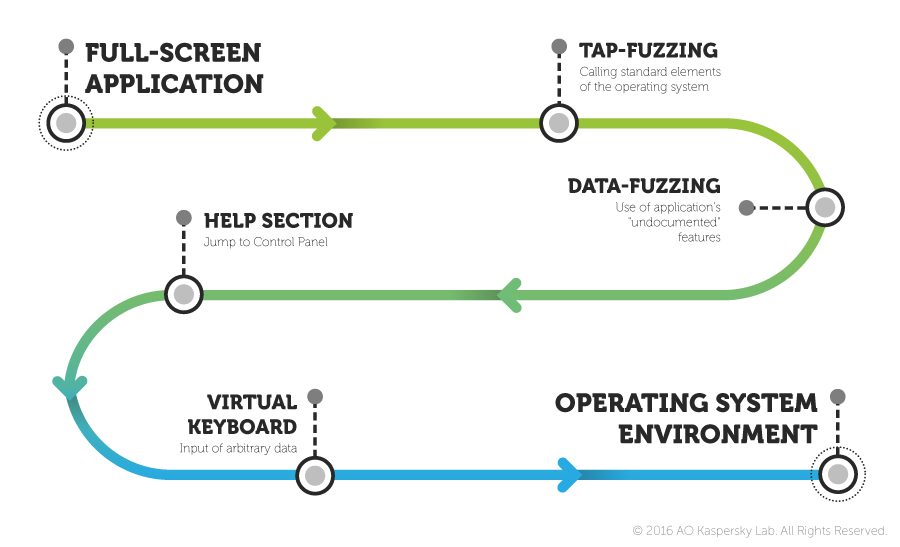

The sequence of operations that can enable an attacker to exit the full-screen application is illustrated in the picture below.

Methodology for analyzing the security of public terminals

Tap Fuzzing

The tap fuzzing technique involves trying to exit the full-screen application by taking advantage of incorrect handling when interacting with the full-screen application. A hacker taps screen corners with his fingers and tries to call the context menu by long-pressing various elements of the screen. If he is able to find such weak points, he tries to call one of the standard OS menus (printing, help, object properties, etc.) and gain access to the on-screen keyboard. If successful, the hacker gets access to the command line, which enables him to do whatever he wants in the system – explore the terminal’s hard drive in search of valuable data, access the Internet or install unwanted applications, such as malware.

Data Fuzzing

Data fuzzing is a technique that, if exploited successfully, also gives an attacker access to the “hidden” standard OS elements, but by using a different technique. To exit the full-screen application, the hacker tries filling in available data entry fields with various data in order to make the ‘kiosk’ work incorrectly. This can work, for example, if the full-screen application’s developer did not configure the filter checking the data entered by the user properly (string length, use of special symbols, etc.). As a result, the attacker can enter incorrect data, triggering an unhandled exception: as a result of the error, the OS will display a window notifying the user of the problem.

Once an element of the operating system’s standard interface has been brought up, the attacker can access the control panel, e.g., via the help section. The control panel will be the starting point for launching the virtual keyboard.

Other Techniques

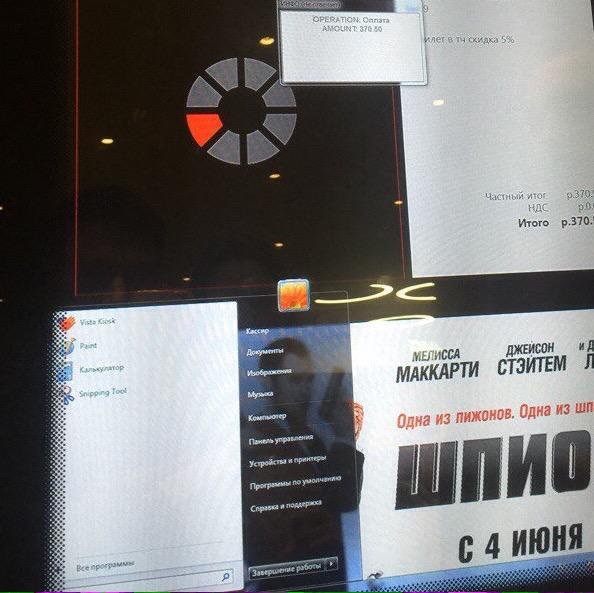

Yet another technique for exiting the ‘kiosk’ is to search for external links that might enable the attacker to access a search engine site and then other sites. Due to developer oversight, many full-screen applications used in terminals contain links to external resources or social networks, such as VKontakte, Facebook, Google+, etc. We have found external links in the interface of cinema ticket vending machines and bike rental terminals, described below.

One more scenario of exiting the full-screen application is using standard elements of the operating system’s user interface. When using an available dialog window in a Windows-based terminal, an attacker is sometimes able to call the dialog window’s control elements, which enables him to exit the virtual ‘kiosk’.

Exiting the full-screen application of a cinema ticket vending terminal

Bike Rental Terminals

Cities in some countries, including Norway, Russia and the United States, are dotted with bicycle rental terminals. Such terminals have touch-screen displays that people can use to register if they want to rent a bike or get help information.

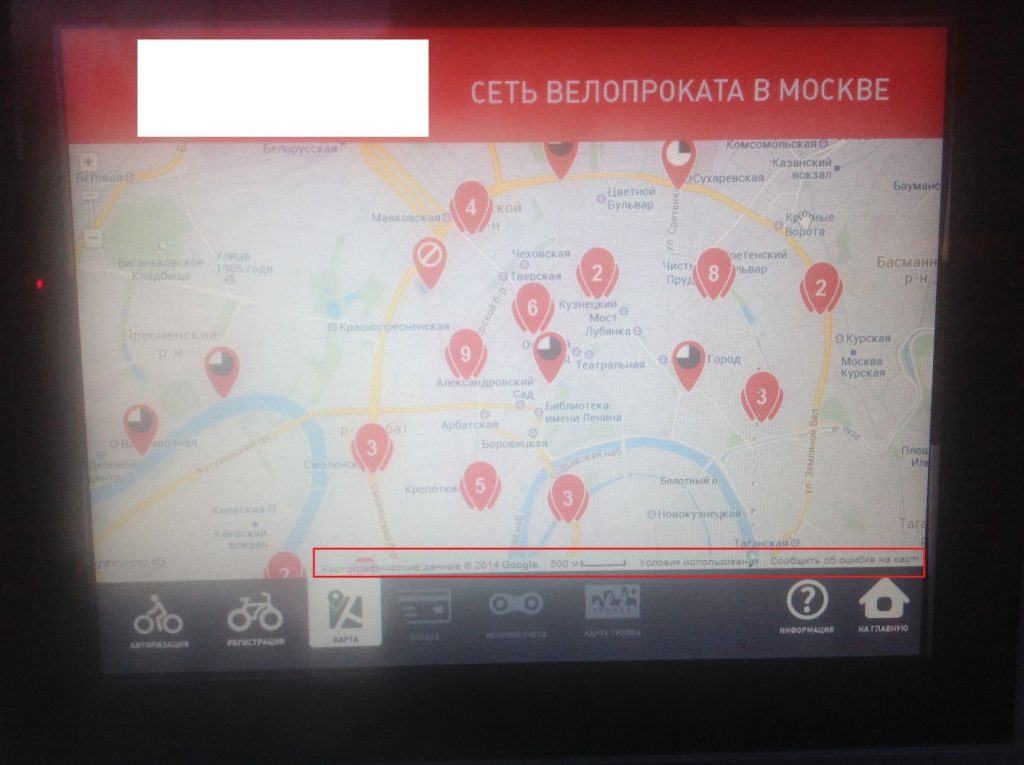

Status bar containing a URL

We found that the terminal system shown above has a curious feature. The Maps section was implemented using Google maps, and the Google widget includes a status bar, which contains “Report an Error”, “Privacy Policy” and “Terms of Use” links, among other information. Tapping on any of these links brings up a standard Internet Explorer window, which provides access to the operating system’s user interface.

The application includes other links, as well: for example, when viewing some locations on the map, you can tap on the “More Info” button and open a web page in the browser.

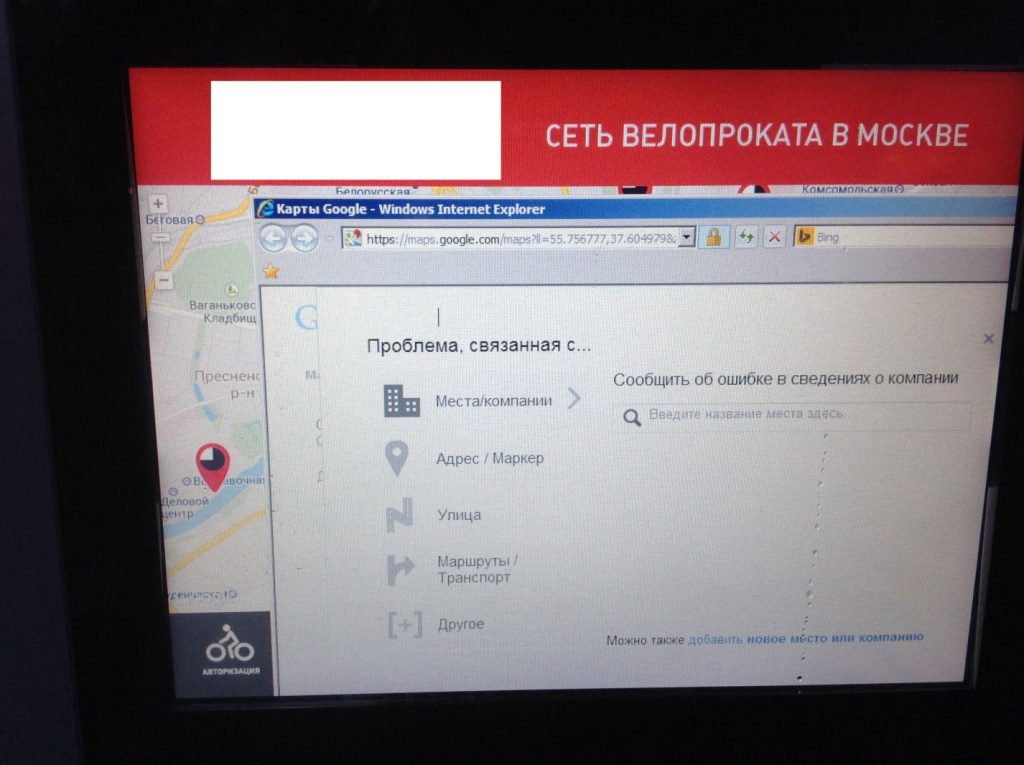

The Internet Explorer opens not only a web page, but also a new opportunity for the attacker

It turned out that calling up the virtual keyboard is not difficult either. By tapping on links on help pages, an attacker can access the Accessibility section, which is where the virtual keyboard can be found. This configuration flaw enables attackers to execute applications not needed for the device’s operation.

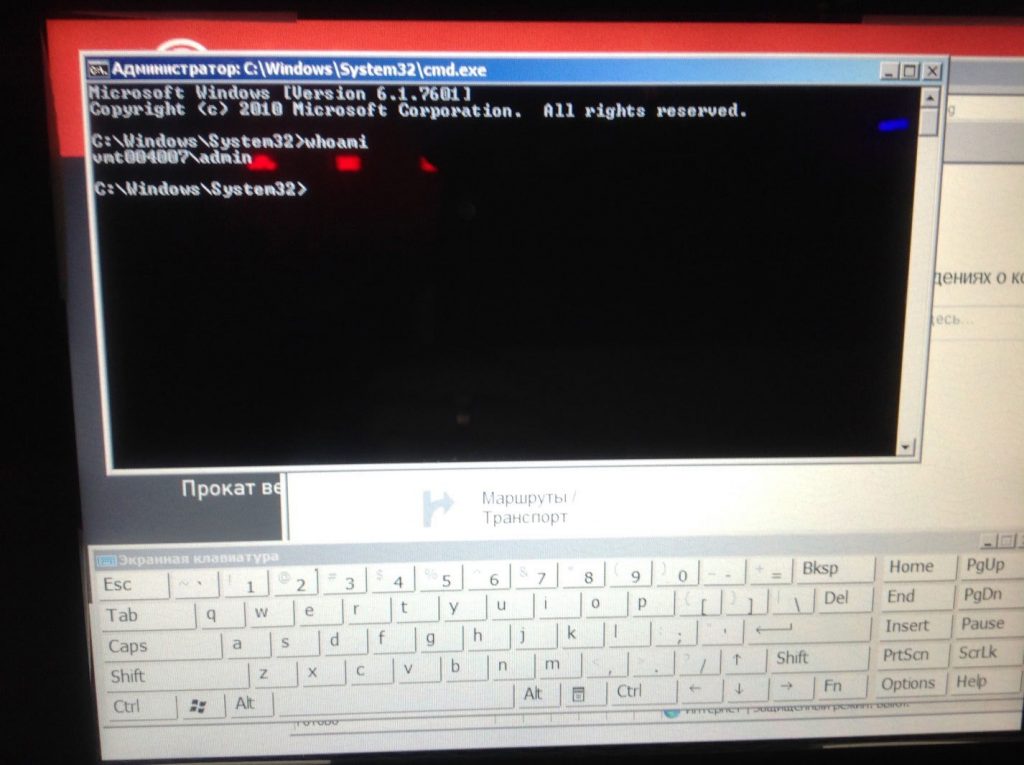

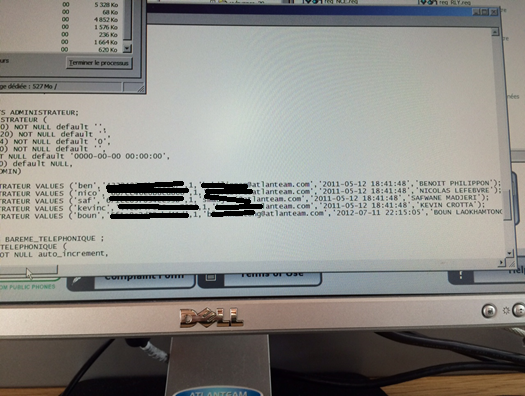

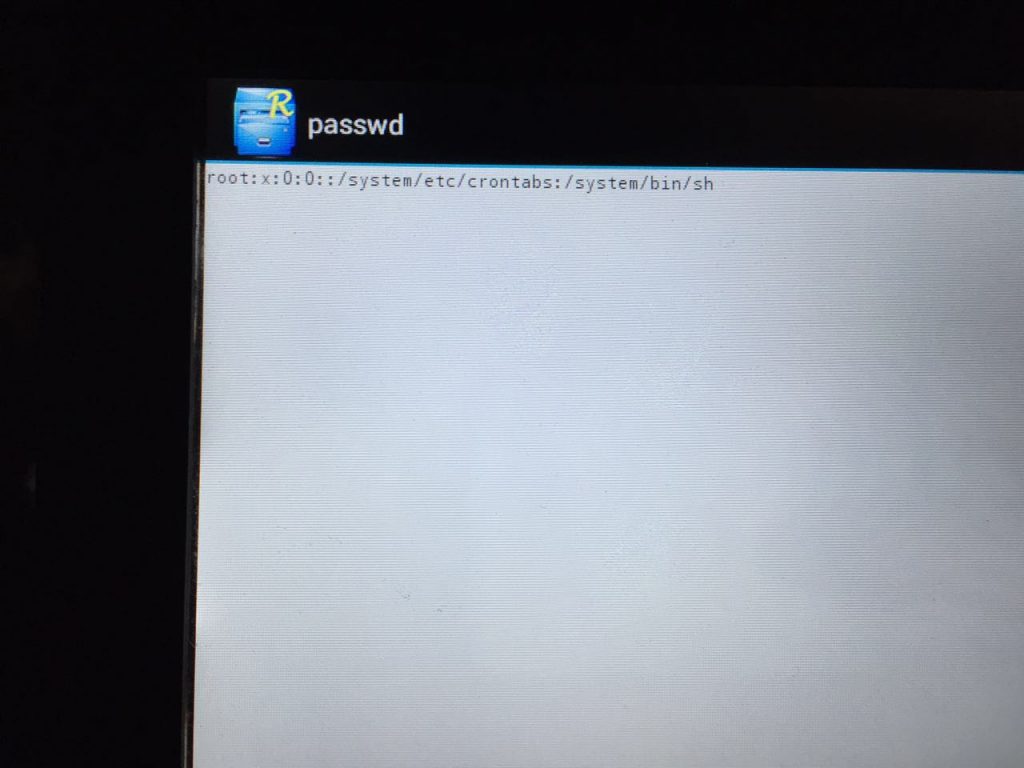

Running cmd.exe demonstrates yet another critical configuration flaw: the operating system’s current session is running with administrator privileges, which means that an attacker can easily execute any application.

The current Windows session is running with administrator privileges

In addition, an attacker can get the NTLM hash of the administrator password. It is highly probable that the password used on this device will work for other devices of the same type, as well.

Note that, in this case, an attacker can not only obtain the NTLM hash – which has to be brute-force cracked to get the password – but the administrator password itself, because passwords can be extracted from memory in plain text.

An attacker can also make a dump of the application that collects information on people who wish to rent a bicycle, including their full names, email addresses and phone numbers. It is not impossible that the database hosting this information is stored somewhere nearby. Such a database would have an especially high market value, since it contains verified email addresses and phone numbers. If it cannot be obtained, an attacker can install a keylogger that will intercept all data entered by users and send it to a remote server.

Given that these devices work 24/7, they can be pooled together to mine cryptocurrency or used for hacking purposes seeing as an infected workstation will be online around the clock.

Particularly audacious cybercriminals can implement an attack scenario that will enable them to get customer payment data by adding a payment card detail entry form to the main window of the bike rental application. It is highly probable that users deceived by the cybercriminals will enter this information alongside their names, phone numbers and email addresses.

Terminals at Government Offices

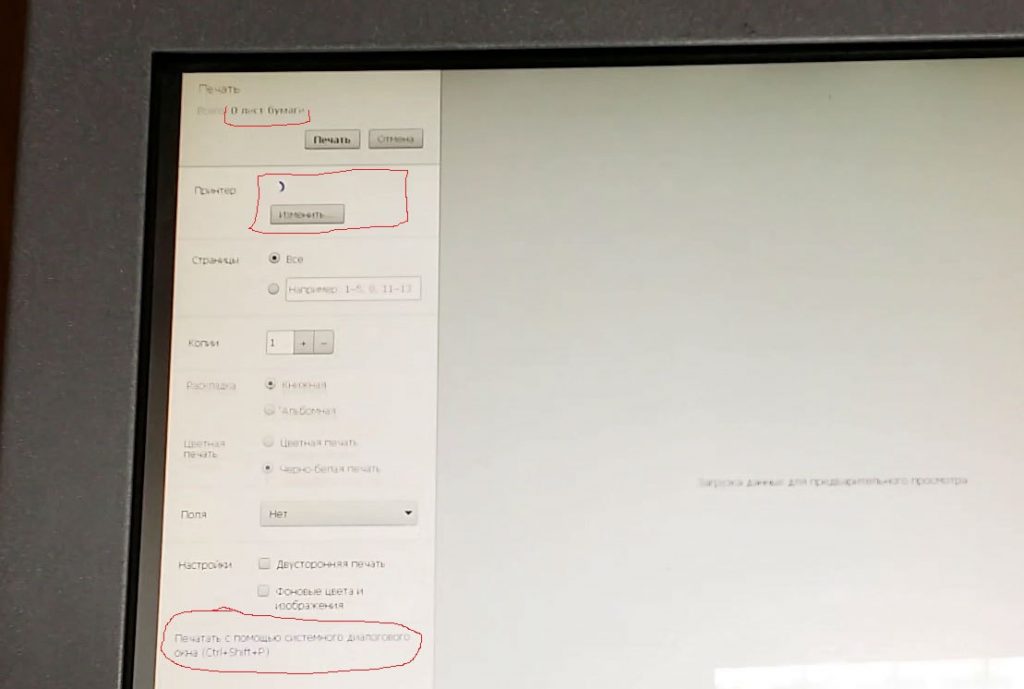

Terminals at some government offices can also be easily compromised by attackers. For example, we have found a terminal that prints payment slips based on the data entered by users. After all fields have been filled with the relevant data, the user taps the “Create” button, after which the terminal opens a standard print window with all the print parameters and control tools for several seconds. Next, the “Print” button is automatically activated.

A detail of the printing process on one of the terminals

An attacker has several seconds to tap the Change [printer] button and exit into the help section. From there, they can open the control panel and launch the on-screen keyboard. As a result, the attacker gets all the devices needed to enter information (the keyboard and the mouse pointer) and can use the computer for their own mercenary purposes, e.g., launch malware, get information on printed files, obtain the device’s administrator password, etc.

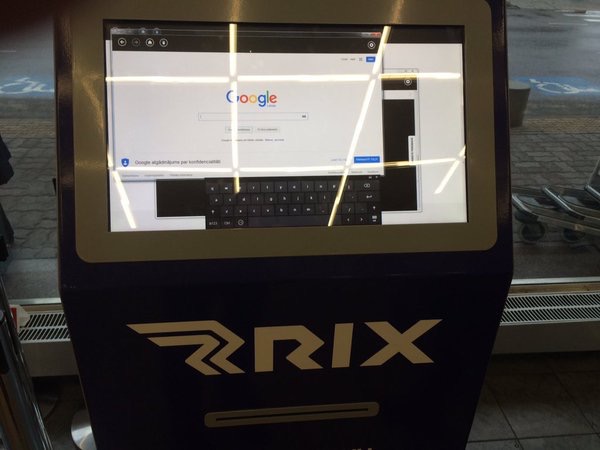

Public Devices at Airports

Self-service check-in kiosks that can be found at every modern airport have more or less the same security problems as the terminals described above. It is highly probable that they can be successfully attacked. An important difference between these kiosks and other similar devices is that some terminals at airports handle much more valuable information that terminals elsewhere.

Exiting the kiosk mode by opening an additional browser window

Many airports have a network of computers that provide paid Internet access. These computers handle the personal data that users have to enter to gain access, including people’s full names and payment card numbers. These terminals also have a semblance of a kiosk mode, but, due to design faults, exiting this mode is possible. On the computers we have analyzed, the kiosk software uses the Flash Player to show advertising and at a certain point an attacker can bring up a context menu and use it to access other OS functions.

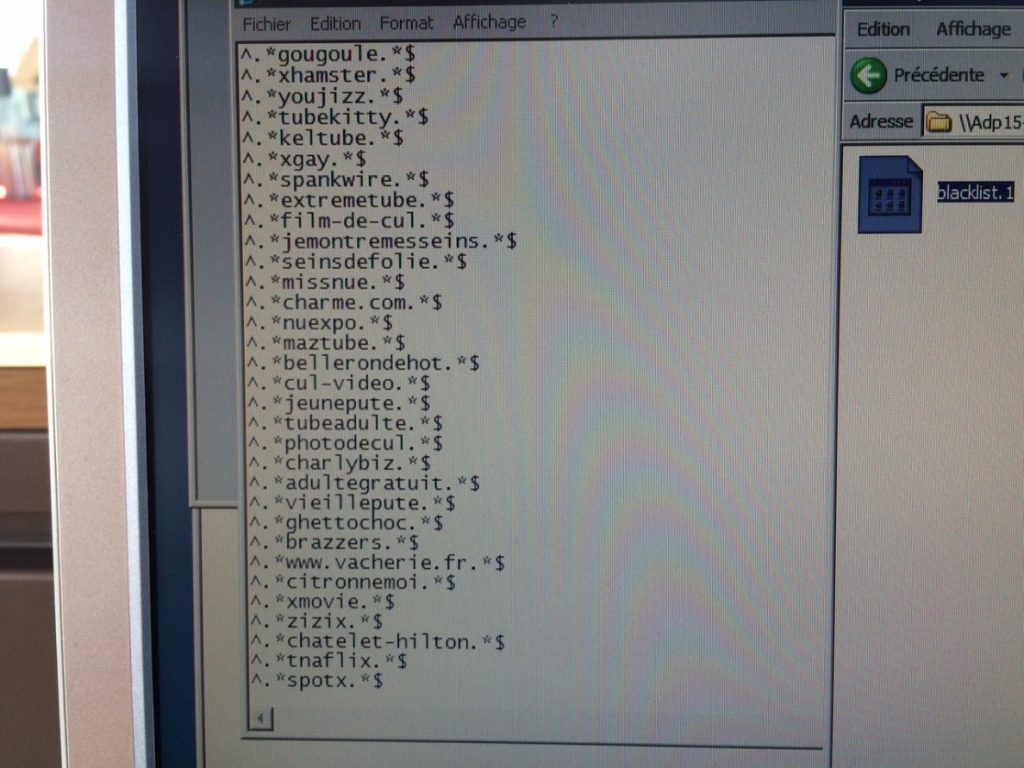

It is worth noting that web address filtering policies are used on these computers. However, access to policy management on these computers was not restricted, enabling an attacker to add websites to the list or remove them from it, offering a range of possibilities for compromising these devices. For example, the ability to access phishing pages or sites used to distribute malware potentially puts such computers at risk. And denylisting legitimate sites helps to increase the chances of a user following a phishing link.

List of addresses blocked by policies

We also discovered that configuration information used to connect to the database containing user data is stored openly in a text file. This means that, after finding a way to exit kiosk mode on one of these machines, anyone can get access to administrator credentials and subsequently to the customer database – with all the logins, passwords, payment details, etc.

A configuration file in which administrator logins and password hashes are stored

Infotainment Terminals in Taxicabs

In the past years, Android devices embedded in the back of the front passenger seat have been installed in many taxicabs. Passengers in the back seat can use these devices to watch advertising, weather information, news and jokes that are not really funny. These terminals have cameras installed in them for security reasons.

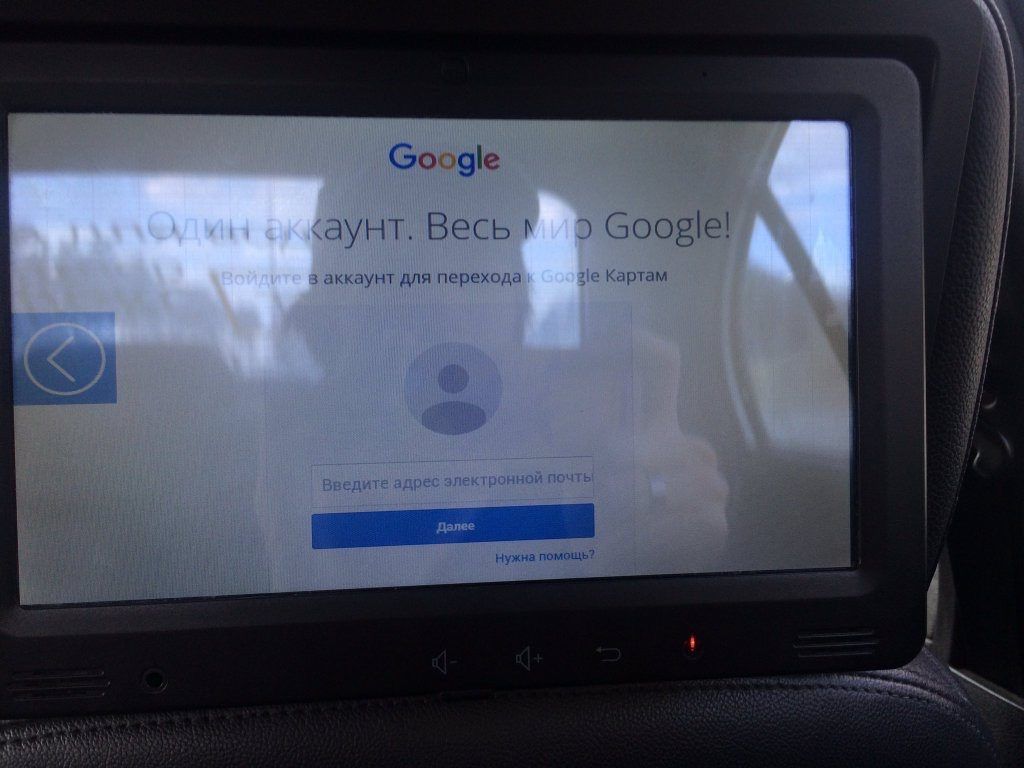

The application that delivers the content also works in kiosk mode and exiting this mode is also possible.

Exiting the kiosk mode on a device installed in a taxi makes it possible to download external applications

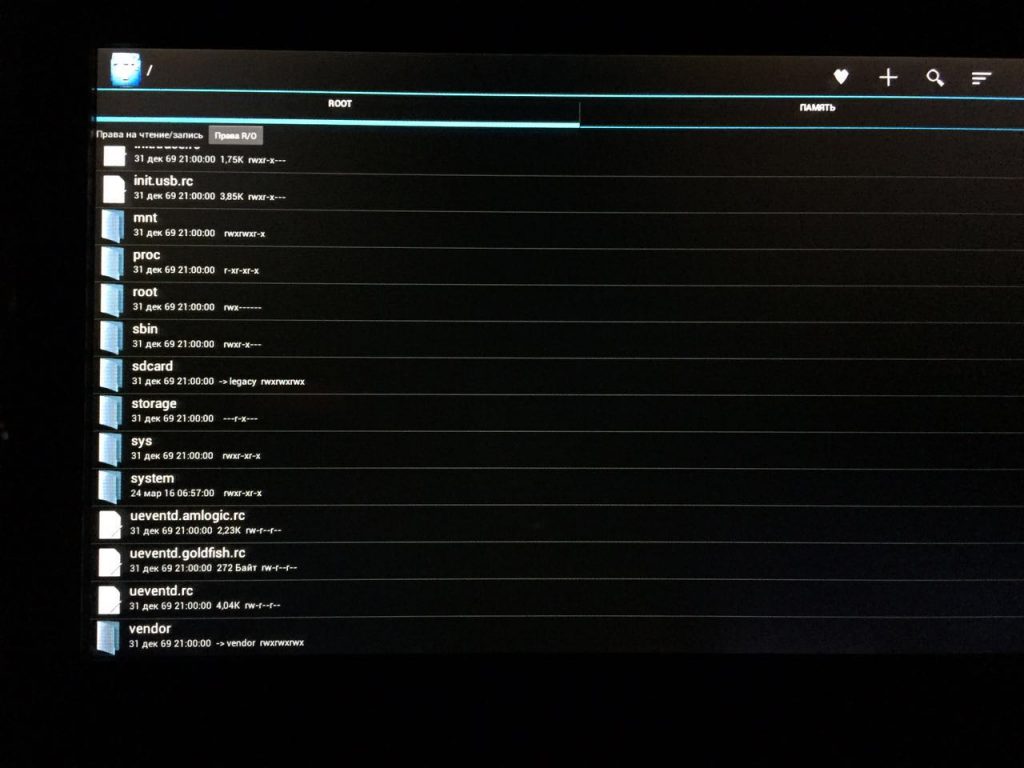

In those terminals that we were able to analyze, there was hidden text on the main screen. It can be selected using standard Android tools using a context menu. This leads to the search option being activated on the main screen. As a result, the shell stops responding, terminates and the device is automatically restarted. While the device is starting, all the hacker needs to do is exit to the main menu at the right time and open the RootExplorer – an Android OS file manager.

Android interface and folder structure

This gives an attacker access to the terminal’s OS and all of its capabilities, including the camera. If the hacker has prepared a malicious application for Android in advance and hosted it on a server, that application can be used to remotely access the camera. In this case, the attacker can remotely control the camera, making videos or taking photos of what is going on in the taxi and uploading them to his server.

Exiting the terminal’s full-screen application in a taxi gives access to the operating system’s functions

Our Recommendations

A successful attack can disrupt a terminal’s operation and cause direct financial damage to its owners. Additionally, a hacker can use a compromised terminal to hack into others, since terminals often form a network. After this, there are extensive possibilities for exploiting the network – from stealing personal data entered by users and spying on them (if the terminal has a camera or document scanner built into it) to stealing money (if the terminal accepts cash or bank cards).

To prevent malicious activity on public devices that have a touch interface, the developers and administrators of terminals located in public places should keep the following recommendations in mind:

- The kiosk’s interactive shell should have no extra functions that enable the operating system’s menu to be called (such as right mouse click, links to external sites, etc.)

- The application itself should be launched using sandboxing technology, such as jailroot, sandbox, etc. This will help to keep the application’s functionality limited to the artificial environment

- Using a thin client is another method of protection. If a hacker manages to ‘kill’ an application, most of the valuable information will be stored on the server rather than the compromised device if the device is a thin client

- The current operating system session should be launched with the restricted privileges of a regular user – this will make installing new applications much more difficult

- A unique account with a unique password should be created on each device to prevent attackers who have compromised one of the terminals from using the password they have cracked to access other similar devices

Elements of the Road Infrastructure

The road infrastructure of modern cities is being gradually equipped with a variety of intelligent sensors, regulators, traffic analyzers, etc. All these sensors collect and send traffic density information to data centers. We looked at speedcams, which can be found everywhere these days.

Speed Cameras

We found speedcam IP addresses by pure chance, using the Shodan search engine. After studying several of these cameras, we developed a dork (a specific search request that identifies the devices or sites with pinpoint accuracy based on a specific attribute) to find as many IP addressed of these cameras as possible. We noticed a certain regularity in the IP addresses of these devices: in each city, all the cameras were on the same subnet. This enabled us to find those devices which were not shown in Shodan search results but which were on the same subnets with other cameras. This means there is a specific architecture on which these devices are based and there must be many such networks. Next, we scanned these and adjacent subnets on certain open ports and found a large number of such devices.

After determining which ports are open on speed cameras, we checked the hypothesis that one of them is responsible for RTSP – the real-time streaming protocol. The protocol’s architecture enables streaming to be either private (accessible with a login and password) or public. We decided to check that passwords were being used. Imagine our surprise when we realized there was no password and the entire video stream was available to all Internet users. Openly broadcast data includes not only the video stream itself, but additional data, such as the geographical coordinates of cameras, as well.

Direct broadcast screenshot from a speed camera

We found many more open ports on these devices, which can also be used to get many interesting technical details, such as a list of internal subnets used by the camera system or the list of camera hardware.

We learned from the technical documentation that the cameras can be reprogrammed over a wireless channel. We also learned from documentation that cameras can detect rule violations on specified lanes, making it possible to disable detection on one of the lanes in the right place at the right time. All of this can be done remotely.

Let’s put ourselves in criminals’ shoes and assume they need to remain undetected in the car traffic after performing certain illegal actions. They can take advantage of speed camera systems to achieve this. They can disable vehicle detection on some or all lanes along their route or monitor the actions of law-enforcement agents chasing them.

In addition, a criminal can get access to a database of vehicles registered as stolen and can add vehicles to it or remove them from it.

We have notified the organizations responsible for operating speed cameras in those countries where we identified the above security issues.

Routers

We also analyzed another element of the road infrastructure – the routers that transfer information between the various smart city elements that are part of the road infrastructure or to data centers.

As we were able to find out, a significant part of these routers uses either weak password protection or none at all. Another widespread vulnerability is that the network name of most routers corresponds to their geographic location, i.e., the street names and building numbers. After getting access to the administration interface of one of these routers, an attacker can scan internal IP ranges to determine other routers’ addresses, thereby collecting information on their locations. After this, by analyzing road load sensors, traffic density information can be collected from these sensors.

Such routers support recording traffic and uploading it to an FTP server that can be created by an attacker. These routers can also be used to create SSH tunnels. They provide access to their firmware (by creating its backup copy), support Telnet connections and have many other capabilities.

These devices are indispensable for the infrastructure of a smart city. However, after gaining access to them, criminals can use them for their own purposes. For example, if a bank uses a secret route to move large amounts of cash, the route can be determined by monitoring information from all sensors (using previously gained access to routers). Next, the movements of the vehicles can be monitored using the cameras.

Our Recommendations

To protect speed cameras, a full-scale security audit and penetration testing must first be carried out. From this, well-thought-out IT security recommendations be prepared for those who provide installation and maintenance of such speed monitoring systems. The technical documentation that we were able to obtain does not include any information on security mechanisms that can protect cameras against external attacks. Another thing that needs to be checked is whether such cameras are assigned an external IP address. This should be avoided where possible. For security reasons, none of these cameras should be visible from the Internet.

The main issue with routers used in the road infrastructure is that there is no requirement to set up a password during initial loading and configuration of the device. Many administrators of such routers are too forgetful or lazy to do such simple things. As a result, gaining access to the network’s internal traffic is sufficiently easy.

Conclusion

The number of new devices used in the infrastructure of a modern city is gradually growing. These new devices in turn connect to other devices and systems. For this environment to be safe for people who live in it, smart cities should be treated as information systems whose protection requires a custom approach and expertise.

This article was prepared as part of the support provided by Kaspersky Lab to “Securing Smart Cities”, an international non-profit initiative created to unite experts in smart city IT security technologies. For further information about the initiative, please visit securingsmartcities.org

Fooling the ‘Smart City’