Introduction

Doxing refers to the collection of confidential information about a person without their consent for the purpose of inflicting harm on that person or to otherwise gain some benefit from gathering or disclosing such information. Normally, doxing involves a threat to specific people, such as media personalities or participants of online discussions. However, any organization can also become a victim of doxing. Confidential corporate information is no less sensitive than the personal data of an individual, and the sheer scale of financial and reputational risks from potential blackmail or disclosure of such information can have a colossal impact.

In the article titled “Dox, steal, reveal. Where does your personal data end up?”, we mentioned that a cybercriminal could attack their victim by using targeted phishing e-mails to obtain access to the victim’s data. But this probably would be an expensive undertaking. However, when doxing is aimed at the corporate sector, cybercriminals are less hindered by the cost of an attack because the potential monetary rewards are much larger. To gather as much confidential corporate information as possible, cybercriminals are employing much more diverse methods than they normally would in their attacks against individual users. We will discuss those methods in this article.

Collecting information about a company from public sources

The first and simplest step that can be taken by cybercriminals is to gather data from publicly accessible sources. The Internet can provide doxers with all kinds of helpful information, such as the names and positions of employees, including those who occupy key positions in the company. Such key positions include the CEO, HR department director, and chief accountant.

For example, if LinkedIn shows that the CEO of a company is “friends” with the chief accountant or head of the HR department, and these persons are also friends with their direct subordinates, a cybercriminal only needs to know their individual names to easily figure out the company’s hierarchy and use this information for subsequent attacks.

In less professionally-oriented social networks such as Facebook, many users indicate their workplace and also publish a large amount of personal information, including recreational photos and the specific restaurants and gyms that they visit. You might think that this kind of information would be useless for an attack on a company because this personal info is not actually related to the company and contains no data that could actually compromise the company or the account owner. However, you would be surprised at how useful this information really could be to a cybercriminal.

Attacks using publicly accessible data: BEC

Information from personal profiles of employees can actually be used to set up BEC attacks. A BEC (Business E-mail Compromise) is a targeted attack on the corporate sector in which a cybercriminal initiates e-mail correspondence with an employee of an organization by posing as a different employee (including their superior) or as a representative of a partner company. The attacker does this to gain the trust of the victim before ultimately persuading the victim to perform certain actions, such as sending confidential data or transferring funds to an account controlled by the attacker. We registered 1,646 unique BEC attacks during February of 2021 alone. Let’s examine a scenario in which information from personal profiles of employees can help cybercriminals achieve their ultimate goals.

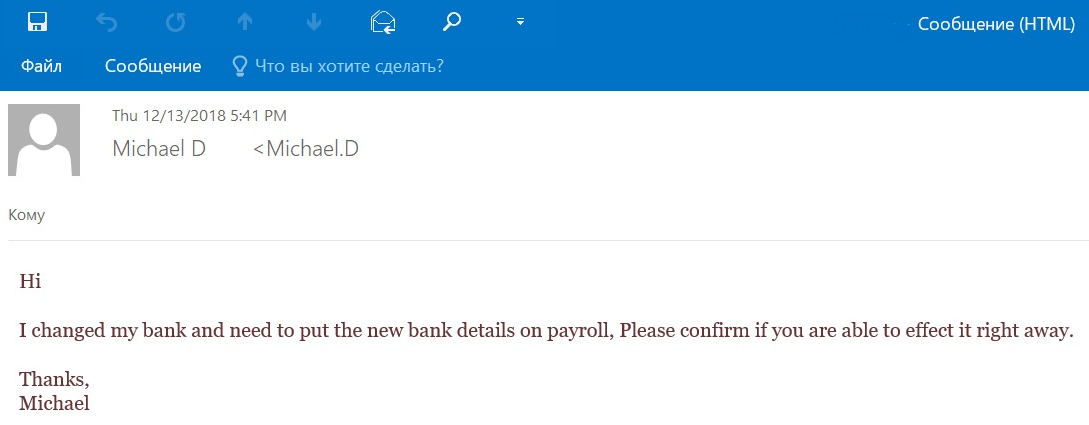

On his own page on a social network, an employee of a large company publishes an innocent photo with an ocean view and a comment stating that he still has three more weeks of vacation. A few days later, the company account department’s mailbox receives an e-mail from the vacationing employee requesting his pay to be deposited to a card in a different bank. The e-mail sender requests that they take care of this as quickly as possible, and explains that he can’t take any calls because he got sick and is not able to speak over the phone.

Example BEC attack with switched bank details

The unsuspecting accountant asks the employee to send his new bank details. After receiving this new banking information, the accountant changes the employee’s data in the system, and payment is sent to the new bank account some time later. However, a few weeks later, the clueless employee returns from vacation without a penny to his name and is dying to know why the accountant never sent his money.

After a little investigation, they determine that the e-mail regarding payment had been sent by cybercriminals who found out from the employee’s social network post that he was on vacation and temporarily unreachable. Although they used the real first and last name of the employee, the fraudulent message had been sent from a spoofed domain that was very similar to the domain of the organization (more details about this technique can be found in this article).

BEC attacks as a means to collect data

In the example above, the goal of the cybercriminals was a one-time financial profit. However, as we mentioned earlier, BEC attacks can also be aimed at obtaining confidential information. Depending on the position of the employee or the importance of the partner being impersonated by the cybercriminals, they could obtain access to fairly sensitive documents such as contracts or customer databases. In addition, cybercriminals may not limit themselves to just one attack, but could use any acquired information to pursue a larger goal.

Leaked data

Confidential documents that end up in the public domain either by carelessness or from malicious intent can also help cybercriminals to complete a dossier on a company. Over the past few years, there has been a notable increase in data breaches related to data stored in the cloud. Most of these breaches occur with Amazon AWS Simple Cloud Storage (AWS S3) due to the widespread popularity of this system as well as the apparent simplicity of its configuration, which does not require any special knowledge of information security. This simplicity is what ultimately poses a danger to the owners of file repositories in AWS known as “buckets”, which are most often breached due to an incorrect system configuration. For example, in July of 2017, the data of 14 million Verizon users was breached due to incorrectly configured buckets.

Tracking pixel

Cybercriminals may resort to various technical tricks to obtain information relevant to their particular goals. One of these tricks is to distribute e-mail messages containing tracking pixel that are often disguised as some type of “test” messages. This technique enables attackers to obtain data such as the time the e-mail was opened, the specific version of the recipient’s mail client, and the IP address, which could help find out the approximate location of the recipient. Using this information, cybercriminals can build a profile on a specific person whom they can then impersonate in subsequent attacks. Specifically, if scammers know the daily schedule and time zone of an employee, they can choose the most ideal time to conduct an attack.

Here’s one example of doxing through the use of a tracking pixel, in which the CEO of a large company receives so-called “test messages” whose contents may slightly vary.

Example test message containing a tracking pixel

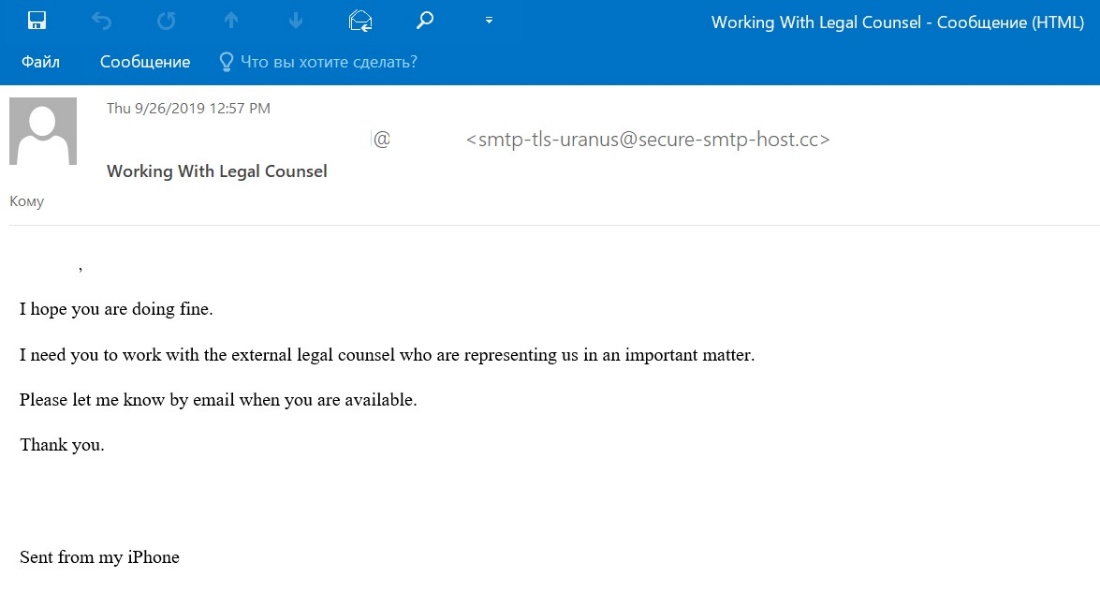

Messages arrive from different domains and at different times. Some come at the peak of the workday, and some come late at night. The latter are opened by the company CEO almost immediately after they arrive to work. Those “test messages” continue to arrive for approximately a week, and then abruptly stop. The CEO thinks the incident is some kind of joke and quickly forgets about it. However, it soon turns out that the company has transferred a few million dollars to the address of an outside company. An investigation reveals that someone claiming to be the CEO had sent several e-mails demanding that the company accountants immediately pay for services rendered by the outside company. This scenario matches one variant of a BEC attack known as a CEO fraud attack, in which cybercriminals pose as top managers of organizations.

Example e-mail used to initiate a CEO fraud attack

In this scenario, cybercriminals found out the work schedule of their targets by using “test messages” containing a tracking pixel that they sent not only to the CEO but also to specific accounting employees. They were then able to request the transfer of a large sum of money supposedly on behalf of the CEO at an ideal time when the CEO was unreachable, but the accounting department was already online.

Phishing

Despite their seemingly primitive simplicity, e-mail phishing and other malicious attacks still serve as some of the main tools used by cybercriminals to gather corporate data. These attacks usually follow a standard scenario.

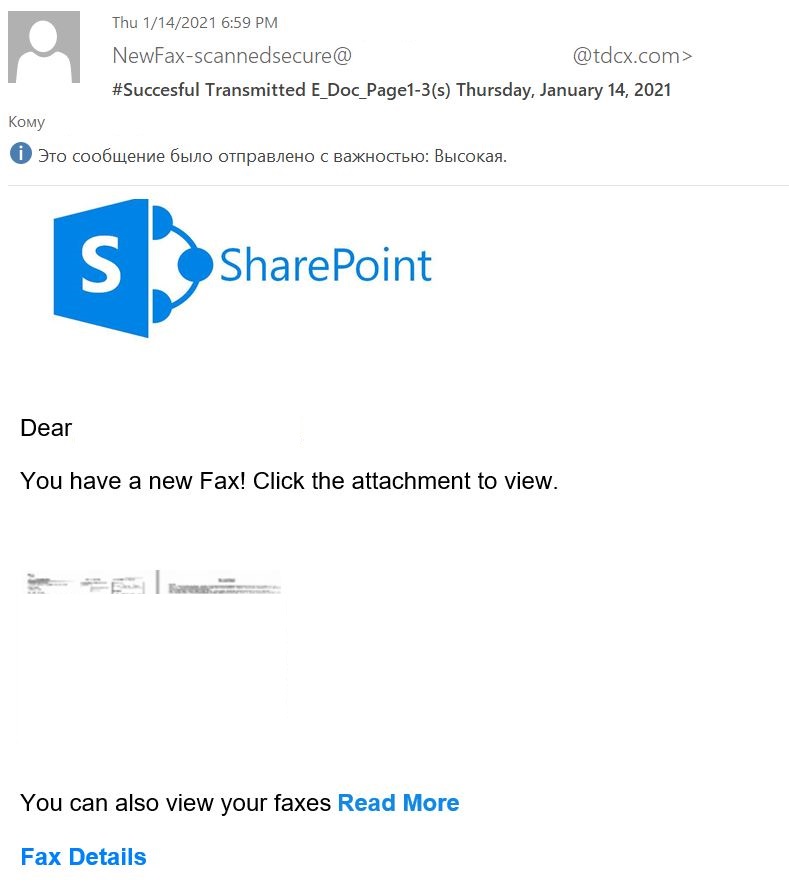

Corporate e-mail addresses of employees receive messages that imitate typical notifications coming from business platforms such as SharePoint. These messages urgently ask the employees to follow a link to either read an important document or perform some other important action. If employees actually follow the recommendations of this e-mail, they will end up on a spoofed website containing a fraudulent form for entering their corporate account credentials. If an employee attempts to log in to this fake resource, this login information will end up in the hands of the phishing scammers. If a business platform is accessible not only from within the corporate network but also from outside of it, the cybercriminals could then log in to the resource using the employee’s account and collect the information they need.

Example phishing e-mail. An employee is asked to follow a link to read a fax message

The first wave of an attack launched against an organization may also be a phishing ploy aimed at hijacking the personal accounts of employees. Many users are “friends” with their colleagues on social networks and correspond with them in popular messengers, which may include discussions about work-related issues. By gaining access to an employee’s account, cybercriminals can skillfully coax the employee’s contacts into disclosing corporate information.

Luckily, simple mass e-mail phishing is promptly detected by most security products, and more and more users are becoming aware of these types of attacks. However, cybercriminals are resorting to more advanced types of attacks, such as phishing for data over the phone.

Phone phishing

The main difference between phone phishing and typical phishing attacks is that cybercriminals persuade their victim to give them confidential information over the phone instead of via a phishing web page. They also may use various methods to establish contact with their victim. For example, they can directly call specific employees or call around the entire company — if the database of employee contacts ended up in their hands, or they can distribute e-mail messages requesting that the employees call a specific number. The latter example is more interesting, so we will discuss this method in detail.

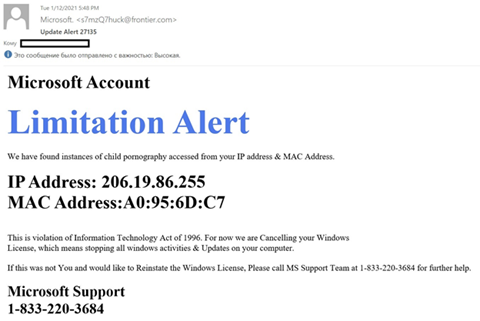

Let’s examine a potential scenario for such an attack. A company employee receives a phishing e-mail that is specially stylized as an official message from a large service provider such as Microsoft. The message contains information that requires the victim to make a quick decision. Cybercriminals may also try to intimidate the recipient. The example below states that child pornography was accessed from the victim’s computer. To resolve the issue, the cybercriminals request that the employee contact technical support at a specific number. If the victim actually calls the specific number, the cybercriminals could pose as Microsoft technical support personnel and dupe the victim into revealing their username and password for accessing the company’s internal systems.

Example e-mail message initiating a phone phishing attack

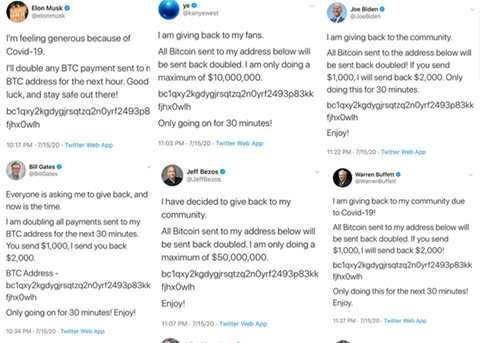

Cybercriminals often pose as technical support personnel or as representatives of the company’s IT department to gain the trust of its employees. This was exactly the technique used for the Twitter hack in the summer of 2020.

By obtaining employee credentials, they were able to target specific employees who had access to our account support tools. They then targeted 130 Twitter accounts – Tweeting from 45, accessing the DM inbox of 36, and downloading the Twitter Data of 7.

— Support (@Support) July 31, 2020

Message from Twitter Support regarding the incident

Twitter employees with access to internal systems of the company received phone calls supposedly from the IT department. During these conversations, cybercriminals employed social engineering techniques to gain access not only to the internal network of the company, but also to tools that enabled them to manage Twitter user accounts. As a result, the pages of many famous people showed fraudulent messages promising their readers that they would receive double any amount that they transferred to a specific bitcoin wallet. More details about this incident can be found in the Twitter company blog.

Examples of scam messages on Twitter

The victims of this incident included the company itself, which incurred reputational losses, and many Twitter users who were duped by the messages from the spoofed posts and actually transferred more than $110,000 in bitcoin. This perfectly illustrates the fact that the initially attacked company is not always the ultimate victim of corporate doxing, but it could be just an unknowing intermediary within a much larger cybercriminal campaign aimed at the company’s customers or partners. Ultimately, the reputation of all involved parties will be damaged.

Doxing of individual employees

Traditional doxing involving the collection of data on specific people could also be used in a larger attack against an organization. As we mentioned earlier, cybercriminals can employ BEC attacks based on specific information acquired from publicly accessible posts on social networks. However, this is not the only potential consequence of doxing, especially for cases of targeted data collection in which the attackers do not limit themselves to publicly available data sources but actually hack the accounts of a victim for the purpose of obtaining access to private content.

Identity theft

One result of doxing aimed at an individual employee may also be theft of their identity. Under a stolen identity, cybercriminals may circulate false information that results in a damaged reputation and sometimes financial losses of a company, especially if this information is attributed to a high-ranking employee whose statements are capable of provoking a serious scandal.

Let’s examine one of the potential attack scenarios involving identity theft. In this scenario, cybercriminals create a fake account for a high-ranking manager of their target company on a social network where the manager has not yet registered, such as Clubhouse. This account participates in discussions with a large number of users, and constantly makes provocative statements that are eventually reported in the media. As a result, company shares may lose value, and potential customers start trending toward the company’s competitors. Interestingly, cases of identity theft have already been observed in Clubhouse (albeit relatively minor cases so far).

Cybercriminals may also pose as a company employee for fraudulent purposes. For example, if a cybercriminal has obtained audio and video content involving the victim, such as from presentations at conferences, broadcasts, or their Instagram stories, the cybercriminal may employ “deepfake” technology. There have already been cases when scammers very convincingly imitated the voice of the CEO of an international company and persuaded the management team of one of their branches to transfer a large sum of money to the scammers.

Conclusion

Corporate doxing poses a serious threat to the confidential data of a company. This article provided examples showing how information that is publicly accessible and generally non-threatening to a company could actually lead to an attack that results in significant financial and reputational losses if such information falls into the hands of professional cybercriminals. The more sensitive the data accessed by cybercriminals, the more damage they are capable of inflicting. They could demand ransom for the confidential information, sell it on the dark web, or use it for subsequent attacks on customers, partners, and company departments responsible for financial transactions.

How to protect yourself

To prevent or minimize the risk of a successful attack on your company, you must first understand that skimping on your security tools is never a good idea. This is especially true in today’s environment, which is continually dealing with new technologies that could be exploited by cybercriminals. To lower the likelihood of confidential data theft:

- Establish a rigid rule to never discuss work-related issues in external messengers outside of the official corporate messengers, and train your employees to strictly adhere to this rule.

- Help your employees become more knowledgeable and aware of cybersecurity issues. This is the only way to effectively counteract the social engineering techniques that are aggressively used by cybercriminals. To do so, you could use an online training platform such as Kaspersky Automated Security Awareness Platform.

- An employee who is well versed in cybersecurity issues will be able to thwart an attack. For instance, if they receive an e-mail from a colleague requesting information, they will know to first call the colleague to confirm that they actually sent the message.

- Utilize anti-spam and anti-phishing technologies. Kaspersky provides several of these types of solutions, which are included in the following business-oriented products: Kaspersky Security for Microsoft Exchange Servers, Kaspersky Security for Linux Mail Server, Kaspersky Secure Mail Gateway, and the standalone product Kaspersky Security for Microsoft Office 365.

Doxing in the corporate sector