Cryptor malware programs currently pose a very real cybersecurity threat to users and companies. Clearly, organizing effective security requires the use of security solutions that incorporate a broad range of technologies capable of preventing a cryptor program from landing on a potential victim’s computer or reacting quickly to stop an ongoing data encryption process and roll back any malicious changes. However, what can be done if an infection does occur and important data has been encrypted? (Infection can occur on nodes that, for whatever reason, were not protected by a security solution, or if the solution was disabled by an administrator.) In this case, the victim’s only hope is that the attackers made some mistakes when implementing the cryptographic algorithm, or used a weak encryption algorithm.

A brief description

The cryptor dubbed Polyglot emerged in late August. According to the information available to us, it is distributed in spam emails that contain a link to a malicious RAR archive. The archive contains the cryptor’s executable code.

Here are some examples of the links used:

hXXp://bank-info.gq/downloads/reshenie_suda.rar

hXXp://bank-info.gq/downloads/dogovor.rar

When the infected file is launched, nothing appears to happen. However, the cryptor copies itself under random names to a dozen or so places, writes itself to the autostart folder and to TaskScheduler. When the installation is complete, file encryption starts. The user’s files do not appear to change (their names remain the same), but the user is no longer able to open them.

When encryption is complete, the cryptor changes the desktop wallpaper, (interestingly, the wallpaper image is unique to each victim) and displays the ransom message.

The cryptor’s main window

New desktop wallpaper with the “open key” block unique to each victim computer

The user is offered the chance to decrypt several files for free.

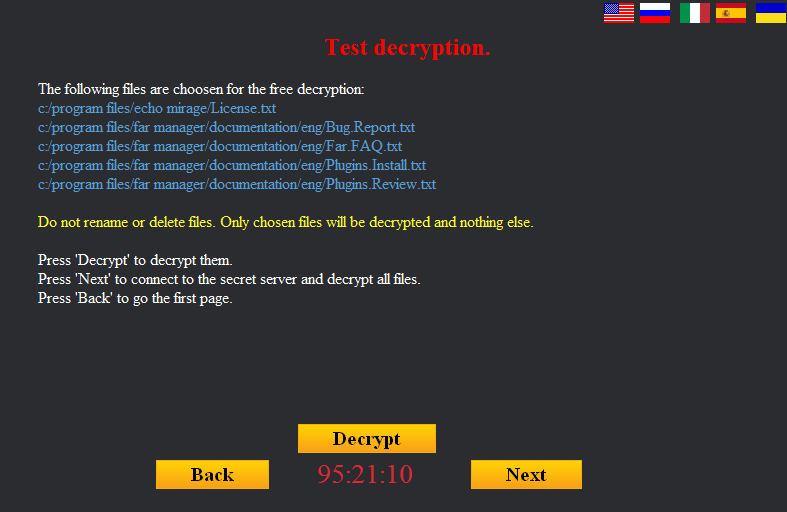

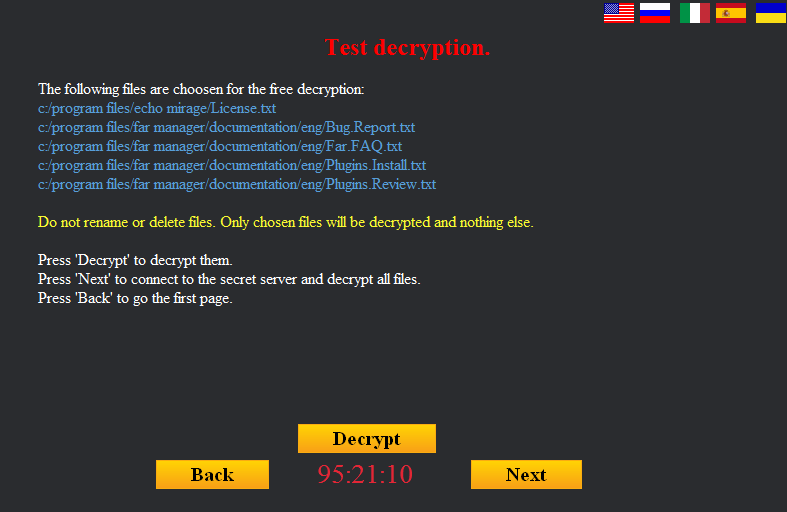

The free trial decryption window

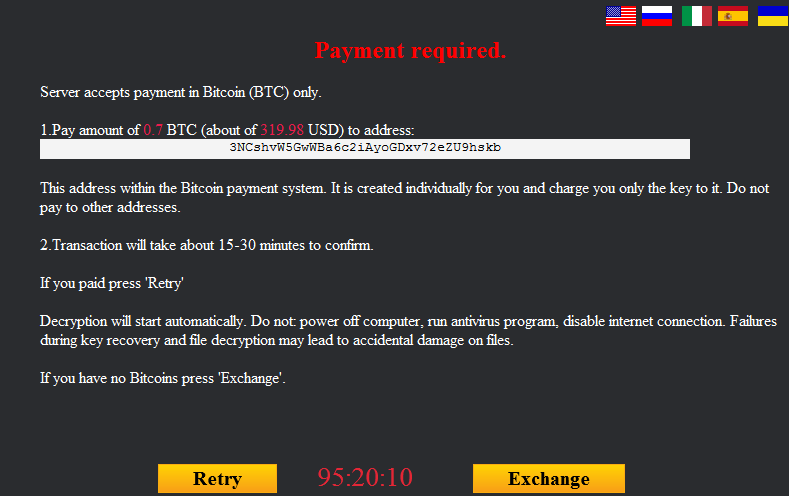

After this, the user is told to pay for file decryption in bitcoins. The cryptor contacts its C&C, which is located on the Tor network, for the ransom sum and the bitcoin address where it should be sent.

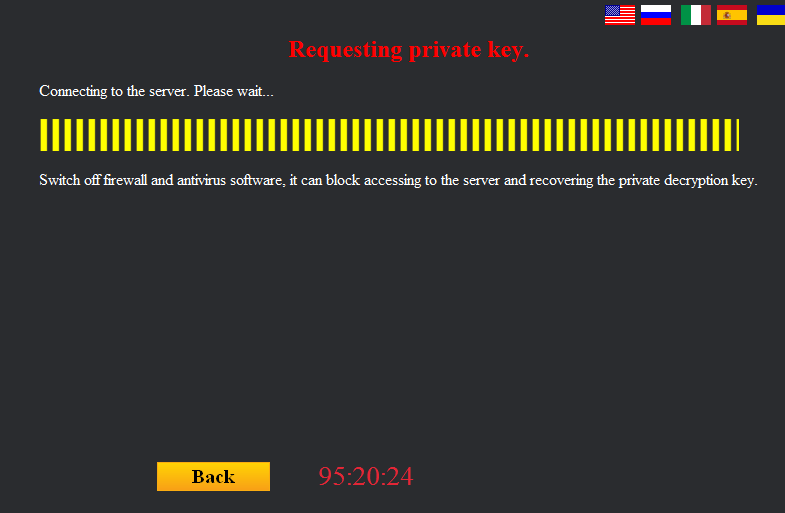

C&C communication window

From this moment on, the cryptor allows the user to check the ransom payment status on the C&C.

Ransom payment details

If the ransom is not paid on time, the cryptor notifies the user that it’s no longer possible to decrypt their files, and that it is about to ‘self-delete’.

Last window displayed by Polyglot

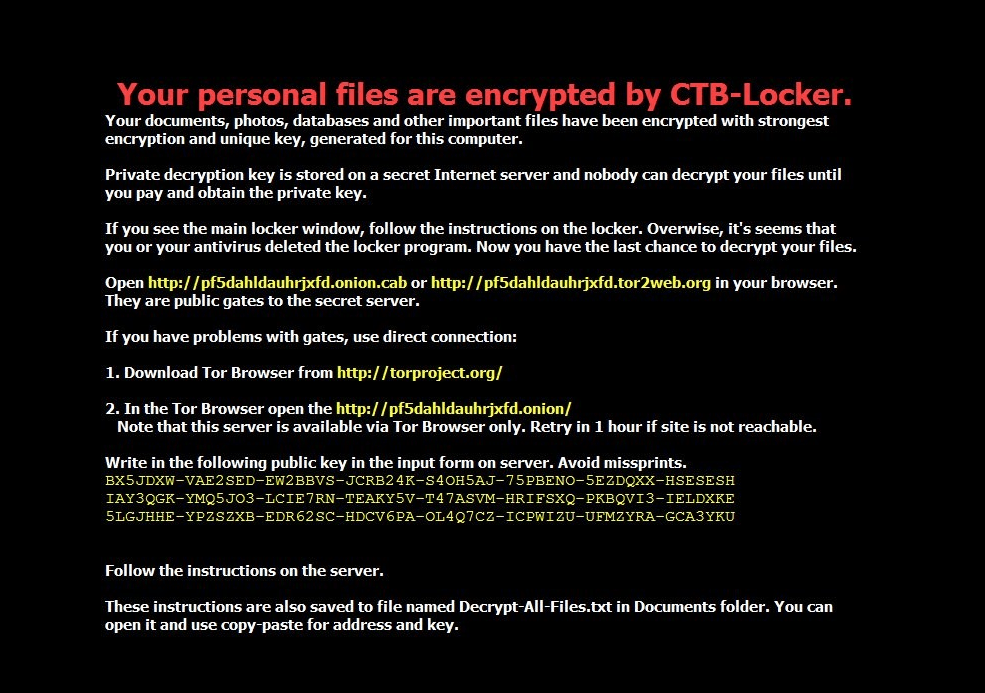

Imitating CTB-Locker

Initially, this cryptor caught our attention because it mimics all the features of another widespread cryptor – CTB-Locker (Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Onion). The graphical interface window, language switch, the sequence of actions for requesting the encryption key, the payment page, the desktop wallpapers – all of them are very similar to those used by CTB-Locker. The visual design has been copied very closely, while the messages in Polyglot’s windows have been copied word for word.

The main graphical interface windows:

List of encrypted files:

Window for the trial decryption of 5 random files:

The private key request window:

The desktop wallpapers:

The ‘connection failed’ error message:

Offline decryption instructions:

The similarities do not stop there. Even the encryption algorithms used by the cybercriminals have clearly been chosen to imitate those used in CTB-Locker.

| Polyglot | CTB-Locker | |

| Algorithms used for file encryption | File content is packed into a ZIP archive and then encrypted with AES-256. | File content is compressed with Zlib and then encrypted with AES-256. |

| Algorithms used while working with the keys | ECDH (elliptic curve Diffie-Hellman), curve25519, SHA256. | ECDH (elliptic curve Diffie-Hellman), curve25519, SHA256. |

| Extensions of encrypted files | File extensions are not changed. | File extensions are changed, depending on version: – .ctbl – .ctb2 – 7 random lower-case Latin symbols |

| Demo decryption | 5 files are decrypted for free as a demo. Their decryption keys and file names are saved in the registry. | 5 files are decrypted for free as a demo. Their decryption keys are only stored in the RAM memory while the process is running. |

| C&C location | C&C is in the Tor network, communication is via a public tor2web service. | C&C is in the Tor network, communication is via a Tor client integrated into the Trojan, or (in some versions of CTB-Locker) via a public tor2web service. |

| Traffic protection / obfuscation | Bitwise NOT operation. | AES encryption. |

That said, we should note the following: a detailed analysis has revealed that Polyglot was developed independently from CTB-Locker; in other words, no shared code has been detected in the two Trojans (except the publicly available DLL code). Perhaps the creators of Polyglot wanted to disorient the victims and researchers, and created a near carbon copy of CTB-Locker from scratch to make it look like a CTB-Locker attack and that there was no hope of getting files decrypted for free.

C&C communication

The Trojan contacts the C&C server located on Tor via a public tor2web service, using the HTTP protocol.

Prior to each of the below data requests, a POST request is sent with the just one parameter: “live=1”.

Request 1.

At the start of operation, the Trojan reports the successful infection to the C&C. The following data is sent to the C&C:

{

“ip”:”xxx.xxx.xxx.xxx”, //ip address of the infected computer

“method”:”register”, //action type. “register” = Trojan informs C&C of new infection

“uid”:”xxxxxxxx-xxxx-xxxx-xxxx-xxxxxxxxxxxx”, //Infected computer’s ID

“version”:”10f”, //Trojan version contained in its body

“info”:”Microsoft (build xxxx), 64-bit”, //OS version on the infected computer

“description”:” “, //Always a whitespace (” “)

“start_time”:”14740xxxxx”, //Trojan’s start time

“end_time”:”0″, //Encryption finish time. 0 = no encryption has run yet

“user_id”:”5″ //Number hardwired in the sample

}

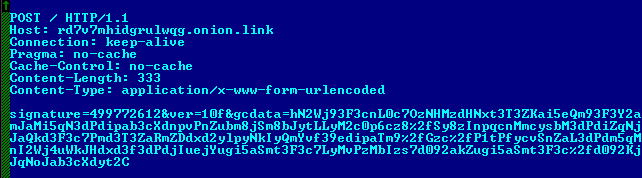

This data block is passed through a bitwise NOT operation, encoded into Base64 and sent to the C&C in a POST request.

Contents of the sent request

Parameters of the POST request:

signature – CRC32 from the sent data

ver – Trojan version

gcdata – data, with contents as described above.

Request 1 and the reply received from the C&C

Request 2.

When the Trojan has finished encrypting the user’s data, it sends another request to the C&C. The content of the request is identical to that of request 1 except the field “end_time”, which now shows the time encryption was completed.

Request 3.

This is sent to the C&C to request the bitcoin address for payment and the ransom sum to be paid.

{

“method”:”getbtcpay”

“uid”:”xxxxxxxx-xxxx-xxxx-xxxx-xxxxxxxxxxxx”

}

The C&C replies to this request with the following data:

{

“code”:”0″,

“text”:”OK”,

“address”:”xxxxxxxx”, //bitcoin address (may vary)

“btc”:0.7, //amount to be paid in BTC (may vary)

“usd”:319.98 //amount to be paid in USD (may vary)

}

Request 4.

This is sent to request a file decryption key from the C&C.

{

“method”:”getkeys”,

“key”:””,

“uid”:”xxxxxxxx-xxxx-xxxx-xxxx-xxxxxxxxxxxx”,

“info”:[“DYqbX3m9u0Pk9bE9Rg2Co3empC2M/yrnqgNS3r0AT2vwCw8Zas08bd4BNiO3XuAqi6/5WQ0VBiUkRUToo+YFL/QtPkiRIQ/D9RyKhzpBHlNpf2hPb9eloDzpkonQl7L6cQyJ2FipEG2ggZOdTDBcNAEAAAA=”]

}

Request 5.

The Trojan reports that data decryption has been completed and states the number of decrypted files to the C&C.

{

“method”:”setend”,

“uid”:”xxxxxxxx-xxxx-xxxx-xxxx-xxxxxxxxxxxx”,

“decrypted”:”1″

}

Description of the encryption algorithm

During our analysis of the malicious code, it became evident that the Trojan encrypts files in three stages, creating intermediate files:

- First, the original file is placed in a password-protected ZIP archive. The archive has the same name as the original file plus the extension “a19”;

- Polyglot encrypts the password-protected archive with the AES-256-ECB algorithm. The resulting file again uses the name of the original file, but the extension is now changed to “ap19”;

- The Trojan deletes the original file and the file with the extension “a19”. The extension of the resulting file is changed from “ap19” to that of the original file.

Flowchart of the search and file encryption actions performed by Polyglot

A separate AES key is generated for each file, and is nothing more than a ‘shared secret’ generated according to the Diffie-Hellman protocol on an elliptic curve. However, first things first.

Before encrypting any files, the Trojan generates two random sequences, each 32 bytes long. The SHA256 digests of each sequence become the private keys s_ec_priv_1 and s_ec_priv_2. Then, the Bernstein elliptic curve (Curve25519) is used to obtain public keys s_ec_pub_1 and s_ec_pub_2 (respectively) from each private key.

The Trojan creates the structure decryption_info and writes the following to it: a random sequence used as the basis for creating the key s_ec_priv_1, the string machine_guid taken from the registry, and a few zero bytes.

| struct decryption_info

{ |

Using the private key s_ec_priv_2 and the cybercriminal’s public key mal_pub_key produces the shared secret mal_shared_secret = ECDH(s_ec_priv_2, mal_pub_key). The structure decryption_info is encrypted with algorithm AES-256-ECB using a key that is the SHA256 digest of this secret. For convenience, we shall call the obtained 80 bytes of the encrypted structure encrypted_info.

Only when Polyglot obtains the encrypted_info value does it proceed to generate the session key AES for the file. Using the above method, a new pair of keys is generated, f_priv_key and f_pub_key. Using f_priv_key and s_ec_pub_1 produces the shared secret f_shared_secret = ECDH(f_priv_key, s_ec_pub_1).

The SHA256 digest of this secret will be the AES key with which the file is encrypted.

To specify that the file has already been encrypted and that it’s possible to decrypt the file, the cybercriminals write the structure file_info to the start of each encrypted file:

| struct file_info

{ |

The elliptic curve, the Diffie-Hellman protocol, AES-256, a password-protected archive – it was almost flawless. But not quite, because the creator of Polyglot made a few mistakes during implementation. This gave us the opportunity to help the victims and restore files that had been encrypted by Polyglot.

Mistakes made by the creators

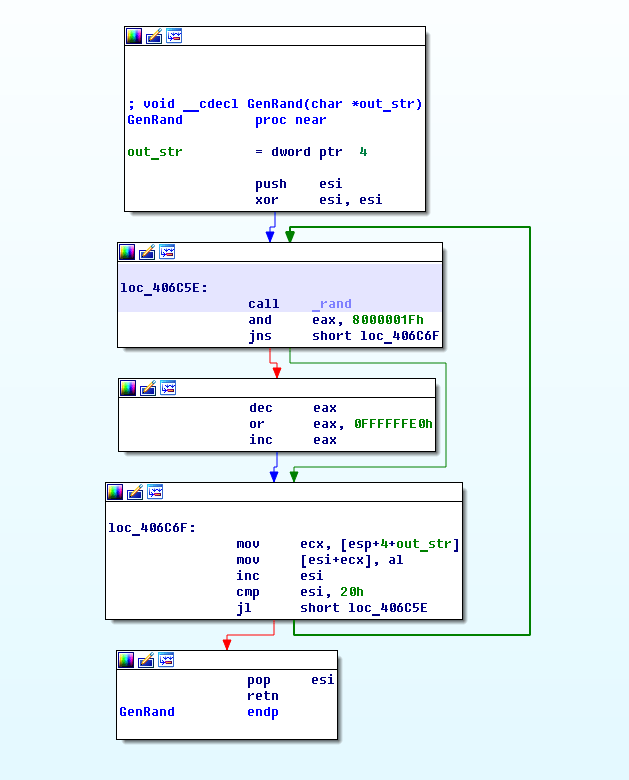

As was mentioned earlier, all the created keys are based on a randomly generated array of characters. Therefore, the strength of the keys is determined by the generator’s strength. And we were surprised to see the implementation of this generator:

A graphical representation of the random sequence generation procedure

Let’s convert this function into pseudocode so it’s easier to follow:

Please note that when another random byte is selected, the entire result of the function rand() is not used, just the remainder of dividing the result by 32. Only the cybercriminal knows why they decided to make the random string this much weaker – an exhaustive search of the entire set of the possible keys produced by such a pseudo-random number generator will only take a few minutes on a standard PC.

Taking advantage of this mistake, we were able to calculate the AES key for an encrypted file. Although there was a password-protected archive below the layer of symmetric encryption, we already knew that the cybercriminal had made another mistake.

Let’s look at how the archive key is generated:

We can see that the key length is only 4 bytes; moreover, these are specific bytes from the string MachineGuid, the unique ID assigned to the computer by the operating system. Furthermore, a slightly modified MachineGuid string is displayed in the requirements text displayed to the victim; this means that if we know the positions in which the 4 characters of the ZIP archive password are located, we can easily unpack the archive.

The MachineGuid string displayed in the requirements screen

Conclusion

Files that are encrypted by this cryptor can be decrypted using Kaspersky Lab’s free anti-cryptor utility RannohDecryptor Version 1.9.3.0.

All Kaspersky Lab solutions detect this cryptor malware as:

Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Polyglot

PDM:Trojan.Win32.Generic

MD5

c8799816d792e0c35f2649fa565e4ecb – Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Polyglot.a

Polyglot – the fake CTB-locker

WhoCares

And next version will get all those fixed.. nice article, but the end user does not understand or care about IDA snippets or TCP dumps.. the author will care and will use it to fix the weak points. Anyway the whole crypto virii thing WAS and IS state sponsored so crypto can get a bad name and all the results coming out of that.. but hey ;D