Introduction

Of all the forms of attack against financial institutions around the world, the one that brings traditional crime and cybercrime together the most is the malicious ecosystem that exists around ATM malware. Criminals from different backgrounds work together with a single goal in mind: jackpotting. If there is one region in the world where these attacks have achieved highly professional levels it’s Latin America.

From “Ploutus”, “Greendispenser”, “Prilex”, traditional criminals and Latin American cybercriminals have been working closely and effectively to steal large sums of money directly from ATMs with quite an elevated rate of success. In order to do it, they have developed a number of tools and techniques that are unique to this region, eventually importing malware from Eastern European cybercriminals and then improving the code to create their own domestic solutions, which they later deploy on a larger scale.

The combination of factors such as the use of obsolete and unsupported operating systems and the availability of easy to use development platforms have allowed the creation of malicious code with technologies such as the .NET framework, without the need for too high technical skills.

We are facing a rising wave of threats against ATMs that have been technically and operationally improved, becoming an immense challenge for financial institutions and security professionals alike. Currently, the attacks on such devices have already generated considerable losses for financial institutions, begging the question: What and when will the next big hit be? “Motivation” is the key word. Why focus on stealing information to monetize it later when it is easier to steal funds directly from the bank?

In this article, we will show an overview on operational details about how these regional attacks against financial institutions have created a unique situation in Latin America. We’ll also highlight how banks and security companies are falling victims to them and how attacks are spreading in the region, aiming to surpass jackpot attacks coming from mariachis and chupacabras.

Dynamite, fake fronts, ATM (in)security

The easiest way to steal money from an ATM machine used to be to blow it up. Most Latin American cybercriminals used to do it on a regular basis. In fact, this type of attack still happens in several parts of the region. Security cameras, CCTV and any other physical security measures proved ineffective in deterring this rudimentary yet extremely effective attack. In many cases, the explosive devices used by the thieves caused damage, not only to the ATMs, but also to bank branches, public squares and the shopping malls in which they were located. A small number of incidents have even caused damage to buildings close to banks.

Explosive attacks on ATMs are a rising problem in Europe as well. In a report covering the first six months of 2016, EAST (European Association for Secure Transactions) reported a total of 492 explosive attacks in Europe; a rise of 80 percent compared to the same period in 2015. Such attacks do not just present a financial risk due to stolen cash, but are also the cause of significant collateral damage to equipment and buildings. Of most concern is the fact that lives can also be placed in danger, particularly by the use of solid explosives.

Actually, it is effortless to find videos on YouTube showing the explosions of ATM machines, mainly in Brazil.

Old school way of robbing an ATM: blowing it up. Some examples here and here.

Old school way of robbing an ATM: blowing it up. Some examples here and here.

In an attempt to stop these attacks, Brazilian banks have adopted ink cartridges to stain the bills when the ATM is blown up. Criminals responded quickly, finding a way to remove the ink from the bills using a special solvent. It’s the eternal cat-and-mouse (or should we say a mouse and cat) game among fraudsters and financial institutions.

Another bold maneuver used commonly by criminals in Latin America is to cover the front of an ATM with a whole fake piece that looks like the original. Such an approach seems to surprise visitors when traveling to our region. This technique was presented to the media by Brian Krebs as the “biggest skimmer of all“. Actually, criminals are able to install it without any complications in a day light in supermarkets and other retail businesses (see video).

ATM fake fascia: what you see is not what you get.

ATM fake fascia: what you see is not what you get.

For criminals, it’s not difficult to build a fake replica of an ATM machine, especially since they can buy the parts needed on the black-market and even on-line stores easily. Here’s an example of an ATM keyboard sold at a regional on-line store (the Latin American eBay). This device helps cybercriminals build whatever they want. Sometimes, criminals find and recruit insiders right from the ATM industry.

You can build your own fake home assemblied ATM, buying it in pieces…

You can build your own fake home assemblied ATM, buying it in pieces…

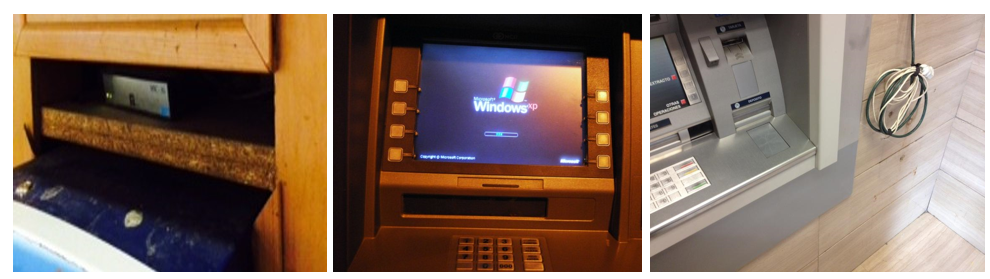

Another worldwide problem affecting ATMs in Latin America is the reliance on obsolete software with several unpatched vulnerabilities, that’s installed and in-use every day in production environments. Most ATMs are still running on Windows XP or Windows 2000, systems that have already reached their end-of-life, and Microsoft has officially ceased to support for them. In addition to the obsolete software, one may frequently find ATMs with completely exposed cables and network devices that are easy to access and manipulate. Such situations are due to insufficient physical security policies, opening a variety of possibilities to the region’s criminals.

Cables and routers exposed in ATMs running Windows XP: a gold mine for scammers.

Cables and routers exposed in ATMs running Windows XP: a gold mine for scammers.

However, such attacks represent a risk for those criminal daredevils as they can be recorded by surveillance cameras while trying to tamper with the machines, inserting a dynamite stick, or installing a fake ATM cover right in front of big brother’s eyes. As banks have enhanced the physical security of ATMs, it is no longer so profitable for criminals to rely on the physical assaults of these, thus giving way to the gradual rise of ATM malware in the region.

The process of stealing money from ATMs using malware typically consists of four stages:

- The attacker gains local/remote access to the machine.

- Malicious code is installed in the ATM system.

- In some cases, to complete the infection process, a reboot of the ATM is needed. Sometimes cybercriminals use umbrella or blackbox schemes to reboot and for their operations support.

- The final stage (and the ultimate goal of the entire process) is withdrawing the money – jackpotting!

Getting access to the inside of an ATM is not a particularly difficult task. The process of infecting is also fairly clear – arbitrary code can be executed on an obsolete (or insufficiently secured) system. There seems to be no problem with withdrawing money either – the malware interface is usually opened by using a specific key combination on the PIN pad or by inserting a “special card”. Sometimes all that is needed is a remote command sent from an already compromised machine in the bank’s network, leaving the “mule” ready for the final step of the game and cashing out without raising any eyebrows.

From Eastern Europe to Latin America

A report from the European ATM Security Team (EAST), shows that global ATM fraud losses increased 18 percent to €156 million (US $177.5 million) in the first half of 2015, compared to the same period in 2014. EAST attributes much of that increase to an 18 percent rise in global card-skimming losses, which includes €131 million (U.S. $149 million) of that total. Unfortunately, it seems there are no official statistics of such attacks and loses in Latin America. ATEFI (the Latin American Association of Service, Operators and Electronic Funds Transfer) does not publish public reports on such attacks.

There is a strong “B2B” cooperation between Eastern European and Latin American cybercriminals. On December 7, 2015, a 26 years old Romanian citizen was arrested in Morelia, Mexico, as he was suspected to be involved in the credit card cloning business. He was caught with $180,000.00 mxn in cash (around $ 9,700.00 USD) after someone from the community reported his suspicious behavior. He had a criminal record in Romania for being a part of an illegal organization connected to counterfeiting and using stolen credit cards. At around the same time, 31 people were arrested in a coordinated police operation and were charged with belonging to a gang dedicated to the credit card cloning business, among them a Cuban citizen, an Ecuadorian citizen, nine Venezuelans, three Romanians, two Bulgarians and 15 Mexicans. This served as further evidence that carders from Europe and Latin America are connected and occasionally work together.

Backdoor.Win32.Skimer was the first malicious program infecting ATM machines that came up back in 2008. Once the ATM was infected using a special access card, criminals were able to perform a number of illegal operations: withdrawing cash from the ATM, or obtaining data from cards used in the ATM. The coder behind it clearly new how ATM hardware and software work. Our analysis of this Trojan concluded that it was designed to target ATM machines in Russia and Ukraine. It works with US dollar, Russian ruble, and Ukrainian hryvnia transactions. More recently, in 2014, we published a detailed post about Tyupkin, an ATM malware found active on more than 50 ATMs in financial institutions in Eastern Europe. We have enough evidence that Latin American cybercriminals are cooperating with the Eastern European gangs involved with ZeuS, SpyEye and other banking Trojans created in that part of the world. This collaboration directly results in the code quality and sophistication of local Latin American malware. Regional cyber criminals also lease the infrastructure of their Eastern European counterparts. The same applies for ATM malware, which is evolving together with other Latin American malware families.

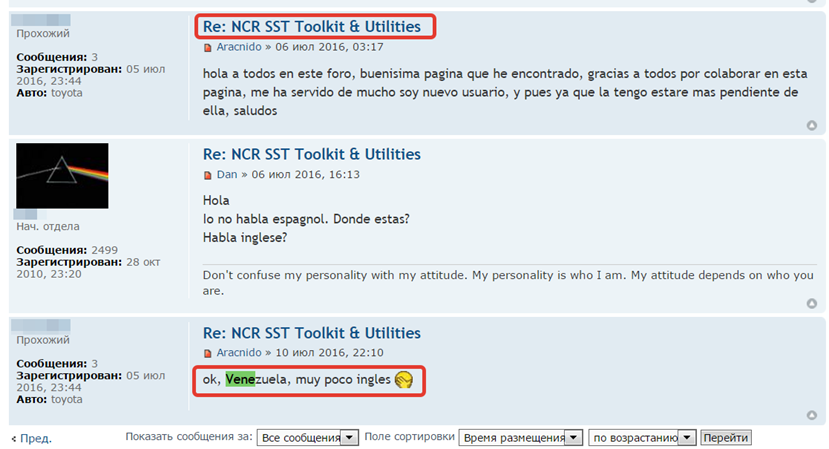

It’s also common to find Latin American criminals on Russian underground forums looking for samples, buying new crimeware packages and exchanging data about ATM/PoS malware, or negotiating and offering their “professional” services. Since most of them are not proficient in Russian, their writing often includes misspelled Russian words as they rely on automated translation services. Sometimes, they just write in Spanish, so Eastern European cybercriminals have to use automated translation. In any case, despite the language barrier, they negotiate use the acquired knowledge to boost the spread of their malware operations in Latin America.

Latin American criminals in the Russian underground: looking for ATM software

Latin American criminals in the Russian underground: looking for ATM software

We believe that the first contacts between both cybercriminal worlds happened back in 2008 or even a little earlier. This is only the tip of the iceberg, as this kind of exchange tends to increase over the years as crime develops and looks for new techniques to attack businesses and end users in general.

Mexico: Ploutus – “god of wealth”

According to Greek mythology, Ploutus represented abundance and wealth; a divine child capable of dispensing his gifts without prejudice. However, in the real world, the economic impact of this rampant malware has been estimated at $ 1,200.000.000 MXN ($ 64,864,864.00 USD), considering that only in Mexico, approximately 73,258 ATMs have been found to be compromised.

The first variant of Ploutus became public in October 24, 2013, uploaded to VirusTotal by someone in Mexico, with the filename ‘ploutus.exe’. At that time, the sample had a low detection rate and some AV companies detected it as a Backdoor.Ploutus – Symantec or Trojan-Banker.MSIL.Atmer – Kaspersky.

During 2014 and 2015, a nation state level investigation in relation to ATM robberies using malware resulted in an increased number of uncovered incidents all over Mexico. In August 2013, investigators finally busted a operation connected to about 450 ATMs from 4 major Mexican banks.

Compromised machines were mostly located in places lacking or with very limited physical surveillance. Malware was deployed either via the CD-ROM drive (in the first versions) or a USB port in latter versions. These attacks caught the attention of the banks’ security departments in an odd manner. The armored transportation company began to receive a rare number of phone calls and alerts in respect to unusually high amounts of money being withdrawn from ATMs. The machines were reporting low cash flow levels just hours after being filled by the company in charge of this service.

The second attack was perpetrated during the Mexican Black Friday, locally known as “El Buen Fin”. During these dates, ATMs are stocked with more money in order to fulfill customer demand (approximately 20% more funds than usual are added). Lastly, the third attack was carried out during Valentine’s Day, which is celebrated on February 14th in Mexico. Dates in which ATMs are heavily used and have more funds than usual certainly attracted the attention of this group, which seemed to plan its attacks in advance while hiding in plain sight.

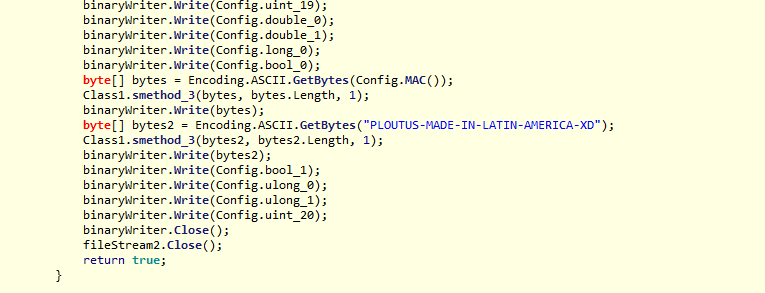

Ploutus developers are not trying to hide the origins of their code.

Ploutus developers are not trying to hide the origins of their code.

To install this malware, physical access to the ATM is needed. Usually, this is achieved via USB or CD drive, facilitating directly from the infected ATM machine and not merely cloning credit or debit cards. So, the damage is for financial Institutions and not their customers, at least not directly.

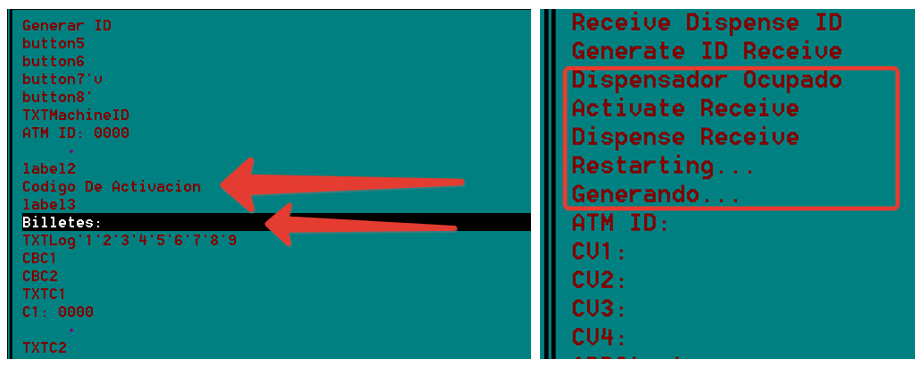

Strings in Spanish language display the goal of Ploutus

Strings in Spanish language display the goal of Ploutus

In this case, the business model is to sell licenses which are valid only for a day, allowing the “customer” (cybercriminal) to withdraw money from any number of machines during that particular day. It may take between two and half to three hours to empty the cash dispensing cassettes of an ATM.

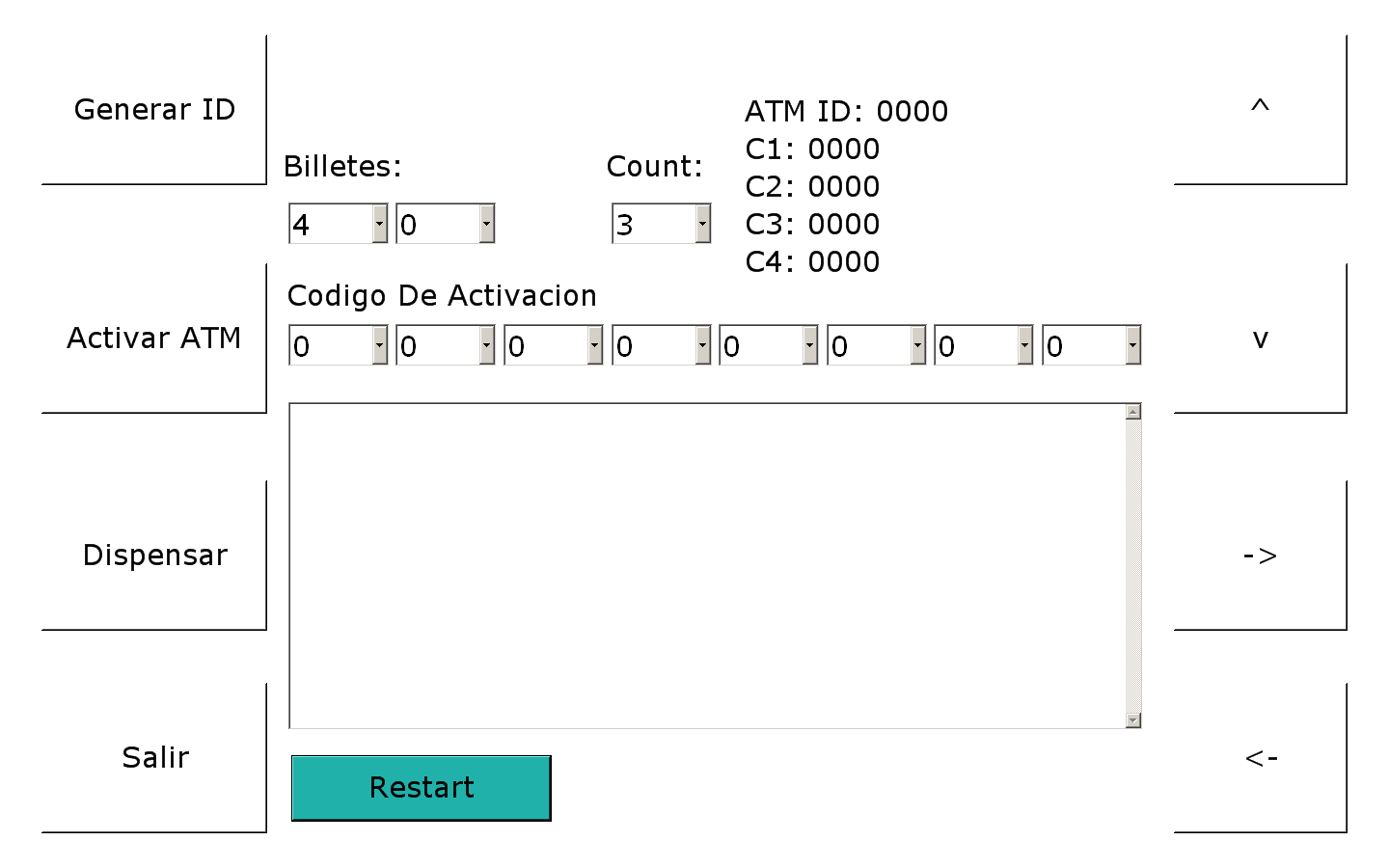

According to a private investigation, a default arrangement for cybercriminals gangs is an average of 3 individuals per cell, with up to 300 people involved in the campaigns. Each group is responsible for compromising a chosen ATM with malware, obtaining an ID that is used afterwards to request an activation code via SMS, allowing full access to all of the ATM’s services.

Graphical user interface of an early version of Ploutus; shown when the correct activation sequence matches.

Graphical user interface of an early version of Ploutus; shown when the correct activation sequence matches.

So far, we have seen four different versions or generations of the Ploutus malware family, the last one, which pertains to 2017, includes bug fixes and code improvements. For the first versions found in-the-wild there was no way of “calling home” or reporting the activities done on the ATM back to a C2 server. However, there is a SMS module used to obtain a unique identifier for the machine that allows the activation of the malicious code remotely. Once activated, money mules (operators standing at the ATM) can start withdrawing money until the licensed time expires. The procedure is as follows:

- Compromise the ATM, via physical access through the CD-ROM drive or USB ports of the machine.

- The install malware will run in the system as a regular Microsoft Windows service.

- Acquire an ATM ID used for the identification and activation of the machine.

- Some versions send a SMS to activate the “customer” (infected ATM), while others require physical access and connecting a keyboard in order to interact with the malware.

- Cash out while the malware is active for 24 hours.

The newest version, found in-the-wild later in 2017, granted criminals full remote administration of infected ATMs and the capability to run diagnostic tools along with other crafted commands. In that latest version we found that cybercriminals switched from a physical keyboard to access ATMs to WiFi access with a special modified TeamViewer Remote management tool module. This made it possible to conduct malicious operations more scalable and less risky for the cybercriminals.

Kaspersky Lab detects the samples described above as Backdoor.MSIL.Ploutus, Trojan-Spy.Win32.Plotus and HEUR:Trojan.Win32.Generic

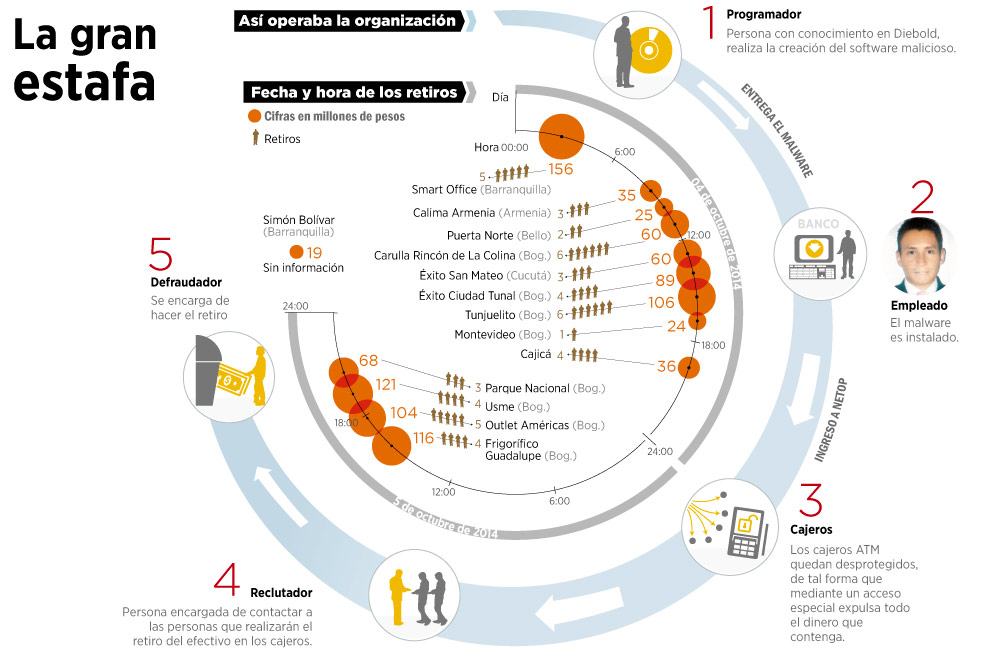

Colombia: corruption, insiders and legit software

In October 2014, 14 ATMs were compromised in different cities of Colombia. The economic impact was around $ 1,024.00 million (Colombian Pesos) without any trackable transaction. Later, an employee at one of the banks was arrested as he was suspected of installing the malware remotely in all of the ATMs using his personal security code and passwords, just one day before resigning his job.

The suspect had previously worked for the Colombian police for 8 years as an electronic engineer specializing in computer security and also as a police investigator. At the time, he was in charge of large-scale investigations, but over the years he ended up leading a judicial file that surprised the investigators. On October 25th, he was arrested and charged by the authorities as the author of a multi-million fraud scheme aimed at a Colombian bank. At the time of his arrest, the criminal had remote access to 1,159 ATMs throughout Colombia. In the development of the illegal operation, the criminal used a modified legitimate ATM software, which left everything set for other members of the illegal organization to commit fraud in less than 48 hours in six different cities. This was the way Colombian media talked about the multi-million fraud against a local bank.

Insider with admin and remote access: 14 ATMs controlled and jackpotted in Colombia

Insider with admin and remote access: 14 ATMs controlled and jackpotted in Colombia

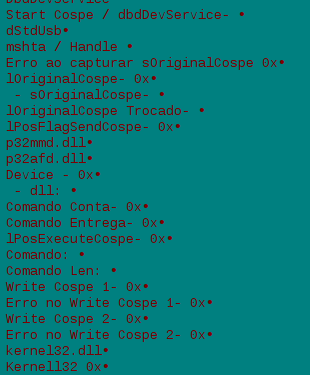

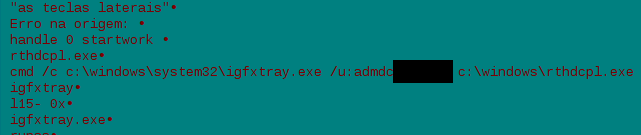

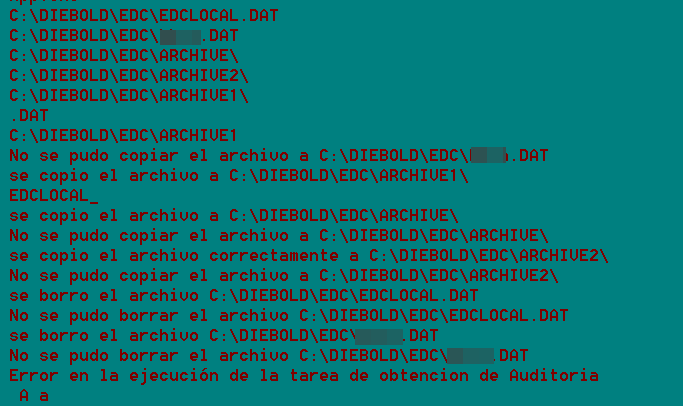

To perform this attack the corrupted ex-police officer used a modified version of the ATM management software distributed by the manufacturer and their technical support staff. As an officer, he had access to this kind of software, which after installation, would interact with the XFS standard, sending commands to the ATM:

Legitimate software, misused: privileged access to steal money.

Legitimate software, misused: privileged access to steal money.

The target in this attack was Diebold ATM machines:

Once the cybercriminal infected the ATMs with the mentioned legitimate but modified management software, a special access was granted. From that moment on, any kind of ATM malware could be installed, including Ploutus, which we saw was aggressively used in Peru and other South American countries.

Kaspersky Lab detects samples of the attack as: Trojan.MSIL.Agent and Backdoor.MSIL.Ploutus

Brazil: Prilex on top of the hill

Brazil is also notorious for developing and spreading locally built malware. The same can be said for their ATM and PoS malware. In 2017, we found an interesting new ATM malware family spread in-the-wild in Brazil. It’s developed from scratch in the country so the code doesn’t have similarities with any other known ATM malware family.

Prilex is an interesting ATM malware fully developed by Brazilian cybercriminals is Prilex. The criminals behind Prilex are also responsible for the development of several PoS malware, allowing them to target both ATM and PoS markets. The key difference of this attack is that instead of using the common XFS library to interact with the ATM sockets, it used some specified vendor’s libraries. Someone generously shared that information with the criminals.

Prilex’s piece of code with a lot of strings in Portuguese.

Prilex’s piece of code with a lot of strings in Portuguese.

According to the code we analyzed, the cybercriminals behind it knew all about victim’s network diagram as well as the internal structure of the ATMs used by the bank. In one of the samples, we found a specific user account of someone working in the Bank. That may mean two things: an insider in the bank was leaking information to cybercriminals or the bank had suffered a targeted attack, which allowed the criminals to exfiltrate key information.

Command used to execute the process under specific credential.

Command used to execute the process under specific credential.

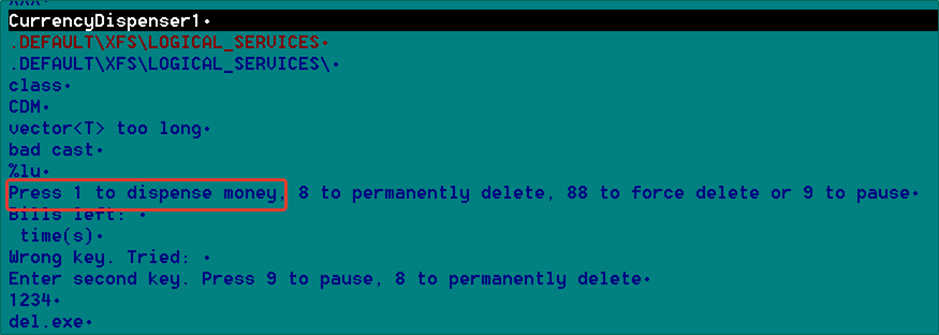

Once the malware is running it has the capability of dispensing money from the sockets by using a special window which is activated by using a specific key combination, provided to the money mules by the criminals. There is also a component which reads and collects data from the magnetic stripe of the cards used it ATMs infected with Prilex. All information is stored in a locally saved file.

We believe that the group behind this malware family is not new. We had seen them running another campaign since at least 2015, not only for ATM but also PoS attacks.

Kaspersky Lab detects this malware family as Trojan.Win32.Prilex.

Conclusion

ATMs have been under constant attack since at least 2008-2009, when the first malicious program targeting ATMs, known as Backdoor.Win32.Skimer, was discovered. This is probably the fastest way for cybercriminals to get money – just right from the ATM. When it happens, we see two losses categories for the banks:

- Direct bank losses, when an attacker obtains money from an ATM cash dispenser.

- Indirect banks losses but losses to its customers. In this second scenario, cybercriminals steal from the customers’ bank accounts cloning unique cardholder data from the users’ ATM (including Track2 – the magnetic stripe data, the PIN – personal identification number used as a password, or new authentication methods, such biometric data).

To achieve their goals, attackers must solve one of these key challenges – they must either bypass customer authentication mechanisms or bypass the ATM’s security mechanisms. Criminals already use various methods to profit from ATMs, such as ram-raiding and dynamite explosive attacks, or traditional skimmers and shimmers to obtain customers’ information. It’s obvious criminal methods are shifting from physical attacks to so-called logical attacks. These can be described as non-destructive attacks. This helps cybercriminals stay undetected for longer periods of time, stealing not just once but several times from the same infected ATM.

ATM security is a complex problem that should be addressed on different levels. Many problems can only be fixed by the ATM manufacturers or vendors, especially with direct cooperation of security vendors.

The vast majority of ATM malware attention is placed on Eastern Europe, as the most developed cybercrime scene is in that part of the world. However, Latin America is one of the most dynamic and challenging markets in the world due to its particular characteristics. Regional cybercriminals are constantly seeking help and trading knowledge with their “colleagues” from Eastern European countries.

The constant monitoring of malicious activities by Latin American cybercriminals provides IT security companies with an advantageous opportunity to discover new attacks related to the financial sector. To have a complete understanding of the Latin American cybercrime scene, antimalware companies need to pay close attention to the reality of the country, collect files locally, build local relationships, and keep local analysts to monitor these attacks, mostly because it’s common for criminals to be extremely vigilant about their creations and how far these propagate. As it happens in Russia and China, Latin American criminals have created their own unique reality that’s sometimes quite difficult to grasp from the outside.

It’s very important for Financial Institutions, being such big and important targets for cybercriminals all over the world, to work on Threat Intelligence, including, not just global feeds, but also IOCs and Yara rules from hard to spot local attacks from regional experts. Our complete IOCs list, as well as Yara rules and full reports are available for Financial Intelligence Reports service customers. Need more information about the service? financialintel@kaspersky.com

Reference hashes

ae3adcc482edc3e0579e152038c3844e

e77be161723ab80ed386da3bf61abddc

acaf7bafb7304e38e6a478c8738d9db3

e5957ccf597223d69d56ff50d810246b

6a103754F6a98dbd7764380FF5dbf36c

c19913e42d5ce13afd1df05593d72634

Bingo, Amigo! Jackpotting: ATM malware from Latin America to the World