I was recently in China for AVAR 2005, the annual meeting of antivirus researchers from Asia and the Pacific. While I was there I did some parallel research on wireless networks in two of China’s major cities, Tianjin and Peking.

The research was conducted between 17th and 19th November 2005, in the business districts of Tianjin and Peking, and also in Peking airport. Data was collected from approximately 300 access points.

I did not attempt to connect to any of the Wi-Fi networks which I detected during the course of the research, nor did I attempt to intercept or decrypt any data being transmitted via the networks. I don’t have any knowledge of Chinese legislation regarding Wi-Fi networks; however, I believe that according to international law, collecting and analysing data is not illegal. This report does not include concrete information (e.g. precise GPS co-ordinates or network names) about the networks detected.

Another area of investigation, in addition to wireless networks, was collecting statistics on the number of Bluetooth devices in ‘visible to all’ mode. I also attempted to collect data on mobile phones infected by mobile malware transmitted via Bluetooth.

This was my first experience of conducting such research; because of this, I admit that I may have interpreted some of the data incorrectly. However, when comparing my statistics to data in similar research, I haven’t found any significant discrepancies or factual errors.

It’s clear that wireless network and mobile device security is an issue which is becoming ever more important. This article is one indication that Kaspersky Lab is taking the issue seriously, and will be working more on it in the future.

Wi-Fi networks

Transmission speed

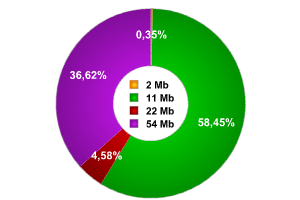

The research clearly shows that the majority of networks (more than 58% of those detected) transmitted data at 11Mbps. 36.2% of networks had a transmission speed of 54Mbps. Some access points functioned at 2Mbps, and were clearly using FHSS.

Transmission speed

Number of access points by transmission speed

Equipment manufacturers

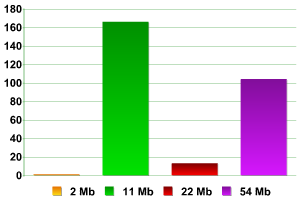

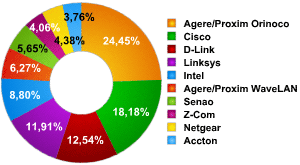

Overall, 21 different types of equipment were detected. Out of these, ten brand names (manufacturers) were most common, being used in 56% of wireless networks in Peking and Tianjin. In 4% of cases, equipment from other manufacturers was used.

The most common equipment brands are as follows:

- Proxim (Agere) Orinoco – 13.73%

- Cisco – 10.21%

- D-Link – 7.04%

- Linksys – 6.69%

- Intel – 4.94%

- Proxim (Agere/WaveLAN) – 3.52%

- Senao – 3.17%

- Z-Com – 2.28%

- Netgear – 2.46%

- Accton – 2.11%

As the data above shows, the overall leaders are Agere Systems (manufacturers of Proxim Orinoco/ WaveLan) at 17.25% and Cisco (manufacturers of Linksys) with 16.9%.

Equipment used as a percentage of the number of networks detected

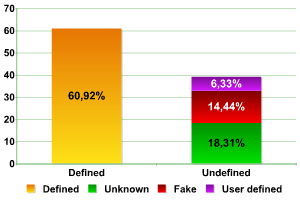

In a significant number of cases (39.08%) the manufacturer was not determined (Unknown, Fake, or User Defined).

Defined / undefined equipment

Traffic encryption

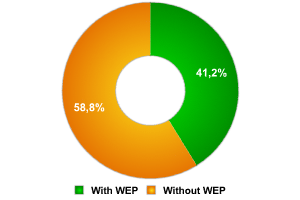

Data from war drivers in cities around the world shows that approximately 70% of wireless networks do not encrypt data in any way. Russian research carried out during 2005, by Informazaschita gave a figure of 69-69% for Moscow (in Russian, first part, second part).

In China, the ratio of protected to unprotected networks differs significantly from rates in the rest of the world.

Encrypted / unecrypted networks

Less than 60% of networks were not using any kind of encryption. However, no networks implementing the new improved encryption standards WPA or 802.11i were detected.

Data provided by war drivers in other countries shows that the router can be accessed via a web browser in a large number of unprotected networks. It’s reasonable to assume that this holds true for Peking and Tianjin, but this aspect was not investigated.

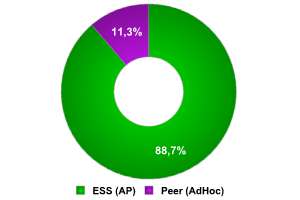

Types of networks

The vast majority of networks detected (89%) are constructed around access points. This figure is similar to that in other countries. The remaining 11% of networks are computer – computer (IBSS/ Peer). In one instance, it was impossible to determine the type of network.

Types of networks

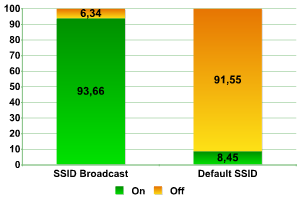

Default configuration

One of the most effective ways of protecting a network against wardriving is to disable SSID. Our research showed that this was implemented in only 6% of networks.

Default SSID is another factor to consider – as a rule, it indicates that the access point administrator has not changed the router name. This may indirectly that the administrator account still uses the default password.

Default configuration

Bluetooth devices

The main aim was to collect statistics on the number of Bluetooth devices in ‘visible to all’ mode, and the type of these devices.

Another goal was to catch viruses in the wild, using a mobile honeypot. The honeypot was in ‘visible to all’ mode, and configured to automatically accept and save all incoming files.

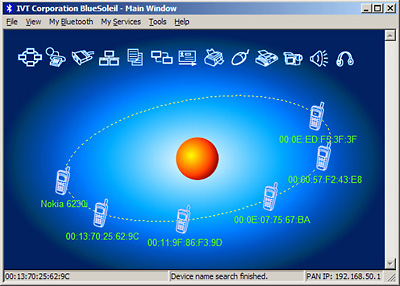

The method used was relatively simple. A laptop with Bluetake (an external BT adaptor) was used, and this had a radius of approximately 100 metres. The software used was BlueSoleil.

In order to gain the maximum number of samples, busy areas were deliberately chosen: the Capital international airport in Peking and Wangfujing, the main shopping street in Peking. Tests were also conducted during the AVAR 2005 conference in Tianjin.

In Peking and Tianjin the main aim was to collect statistics on active Bluetooth devices. The majority of work using the honeypot was undertaken at the airport.

Blue Soleil in scanning mode

I found the research results in both areas surprising.

Altogether, approximately 50 different Bluetooth devices were detected.

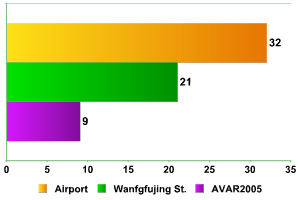

Number of Bluetooth devices

One factor which caught my attention was the relatively small number of Bluetooth devices. The research was conducted over a total of about 12 hours; given the current increase in use of mobile devices throughout the world, and the large numbers of people in the areas where testing was conducted, I expected devices to number in the hundreds, if not higher. At AVAR 2005, I only detected 9 Bluetooth devices, a number which seems to me to be too high; after all, the conference delegates are security experts, and should be aware of the danger of enabling Bluetooth connections, not to mention remaining in ‘visible to all’ mode. However, at the remaining points – Wangfujing and the airport there were far fewer devices detected than I expected.

This is surprising given the large number of people, and the high proportion of foreign tourists, in the areas where research was conducted.

At the moment I can’t explain why there was such a discrepancy between the numbers expected and the real numbers; this issue should be addressed by conducting additional research in other cities.

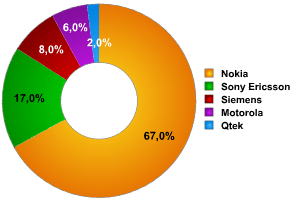

As for the devices detected, the research confirmed the hypothesis (based on data) that Nokia is the overall leader on the smartphone market. I expected to find a wider variety of smartphones, and some PDAs, but was proved wrong.

Equipment manufacturers (%)

The results enable us to answer an important question: which operating system for smartphones is most widely used?

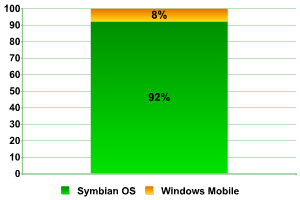

If we put Nokia, Sony Ericsson and Siemens (all running Symbian OS) in one group (and Motorola and Qtek (Windows Mobile) in another, it’s clear which operating system is the market leader.

Operating systems

This shows why we detect so many malicious programs created for Symbian; virus writers are, just as in the case with Windows, choosing to attack the most popular platform.

However, the most surprising results came when we were looking for viruses in the wild. In spite of the fact that our company has had a local office in China for a number of years, and that Kaspersky Anti-Virus is one of the best selling solutions on the Chinese antivirus market, we have never received any reports from Chinese users about infection by mobile malware transmitted via Bluetooth. We know that a number of Cabir variants and a large number of Trojans for Symbian were created in China, but we haven’t had any confirmed cases of infection.

We are keeping track of data on mobile malware epidemics which are regularly published by our Finnish counterparts at F-Secure. According to F-Secure’s data, Cabir was detected in China a year ago, bringing the number of countries with Cabir to over thirty now. As for Cabir in Russia – three months ago I detected Cabir in the wild. The worm was attempting to penetrate my phone while I was peacefully sitting at home – certain confirmation that there is, if not an epidemic, at least an outbreak of Cabir in Moscow.

Given all of the above, I had hoped to get evidence of Cabir in China, and also possibly to detect new, as yet unknown, mobile malware.

As I’ve already stated, I spent 12 hours on this research, five of which were passed at the Peking International Airport. This airport is currently one of the biggest in the world, and once the fifth terminal is completed, it will double in size and be the biggest in the world. The points where I conducted the research were carefully chosen in accordance with the amount of traffic – passport control, check in, the terminal exits e.g. all the points which each passenger leaving Peking passes through. Given the fact that the Bluetooth function in the majority of smartphones has a relatively small radius, I selected the control points so that the distance between the honeypot and the passengers would be no more than 10 meters.

I’ve already mentioned the fact that I detected a relatively small number of Bluetooth devices. Consequently, I wasn’t that surprised when I didn’t detect one single attempt to transmit files to the honeypot. I checked all the hardware and software, and checked the results using my mobile phone. And the result was still zero.

This strange result seems to be related to the fact that only a small number of mobile devices were detected. And as yet, we don’t have any explanation for this. As a comparison, a couple of hours in the Moscow metro will be long enough to detect 50 Bluetooth devices, and these devices will often attempt to transmit files.

I’m now planning to conduct research in Moscow which mirrors that undertaken in China – similar control points located in shopping centers, airports, central and business districts will be used. We’re also planning to create a honeypot network to detect mobile devices, initially in Moscow, and perhaps later extending it to other towns and cities around the world.

If you are interested in the data presented here, and would like to share your ideas, conclusions, and suggestions, please feel free to contact me.

Wardriving in China