And simple ways to get them without investments or SMS

When, back in 2015, push notifications were just appearing in browsers, very few people wondered how this tool would be used in the future: once a useful technology made to keep regular readers informed about updates, today it is often used to shell website visitors with unsolicited ads. To achieve that, users are hoaxed into subscribing to notifications, for example, by passing subscription consent off as some other action. The victim ends up subscribed to ad deliveries, while at the same time quite unable to get rid of the annoying messages, being unaware of their source or origin.

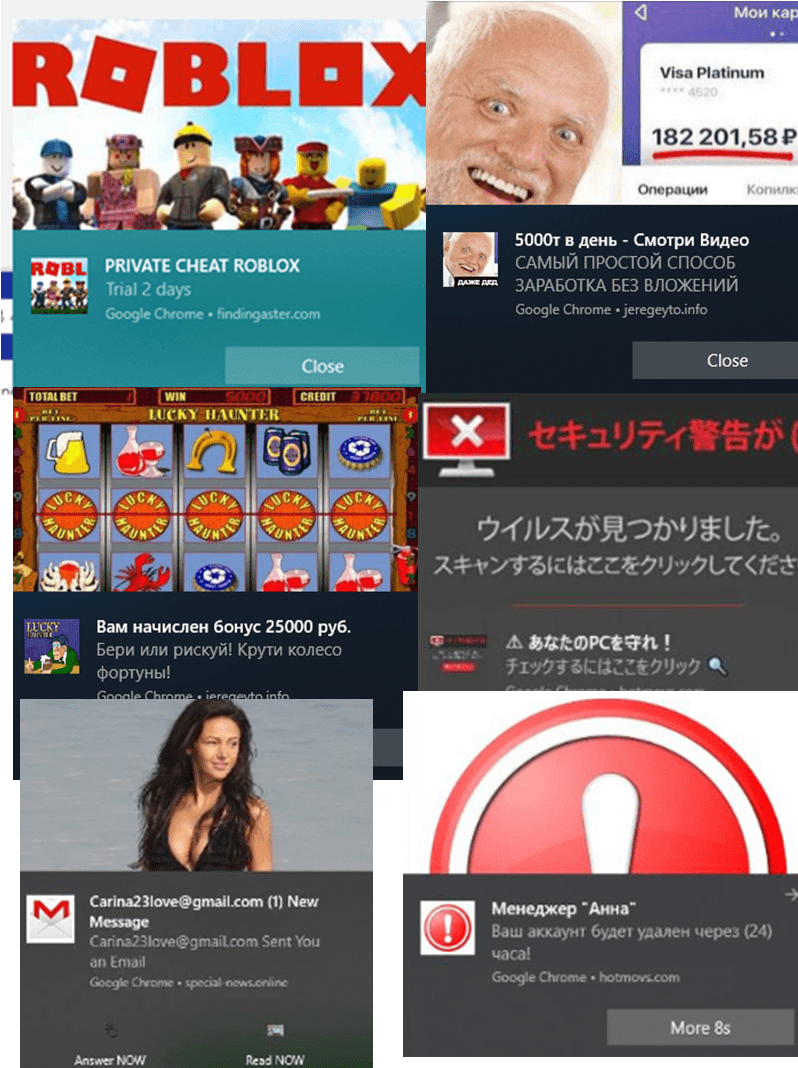

Other than ads, downright scam notifications may also be delivered, such as about lottery wins, or offers of money in exchange for completing a survey. All such proposals are usually phishing attacks seeking to coax users to part with their money. We have repeatedly anatomized such cases in our quarterly spam and phishing reports.

From January 1 through September 30, 2019, Kaspersky Lab products have blocked ad and scam notifications sign up and demonstration attempts on the devices of more than 14 million unique users all over the world. We have observed the highest share of users (of the total number of our product users) hit by unsolicited subscriptions in Algeria (27.2%), Belarus (24.1%), Nepal (23.7%), Kazakhstan (23.6%) and the Philippines (22.2%).

We have also registered an upward trend in the spread of ad and scam subscriptions. Since the turn of the year, the number of users hit by this problem has continued to grow:

Number of users hit by unwanted subscriptions, January – September 2019 (download)

Getting the user subscribed

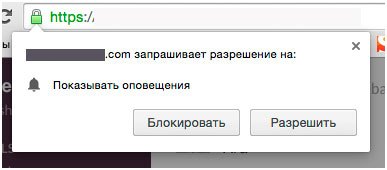

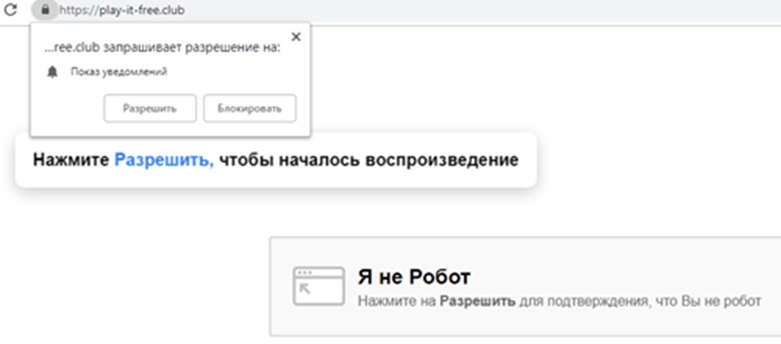

To make users sign up for notifications they don’t need, scammers try to pass the confirmation window off as something else. For example, as CAPTCHA:

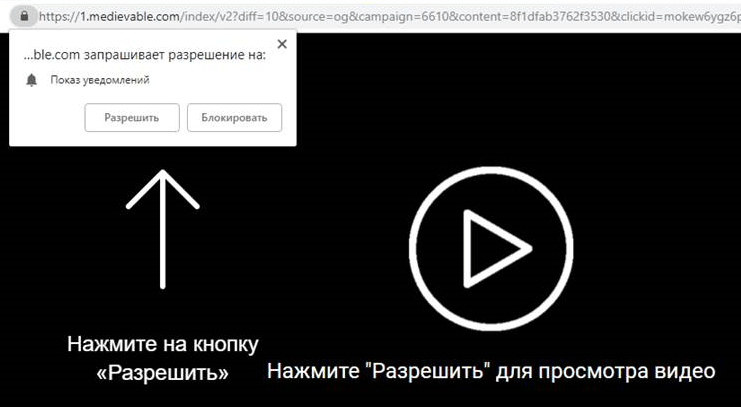

In other instances, clicking “Allow” button is ostensibly needed to play back a video or begin downloading a file:

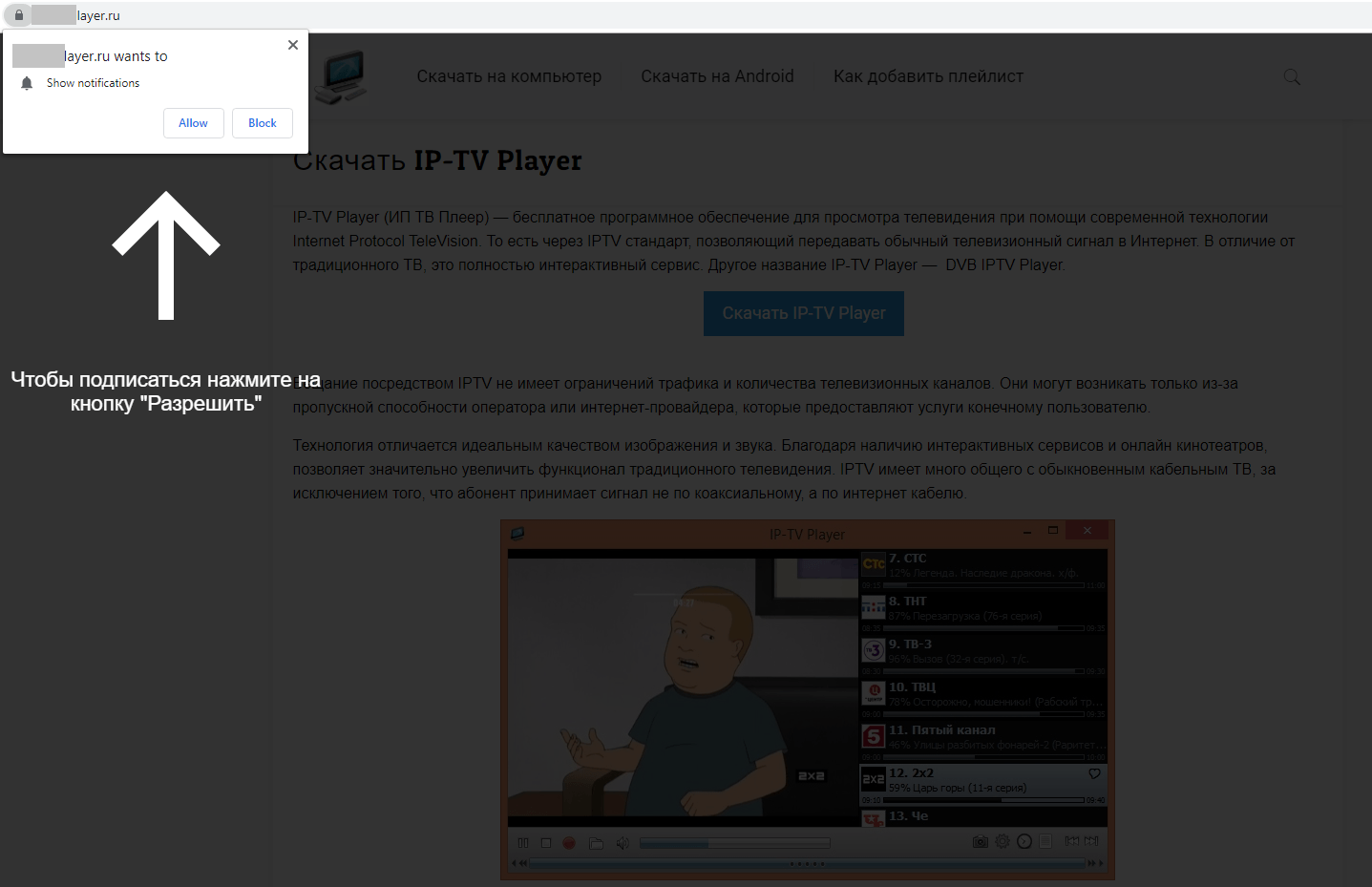

Sometimes the webpage content remains blocked until the user has agreed to sign up for notifications:

Often the victim agrees to receive promotional notifications having been misled to believe that he or she is subscribing to updates on a website of interest. In the case below, a subscription like that is offered by a website ostensibly dedicated to Android devices:

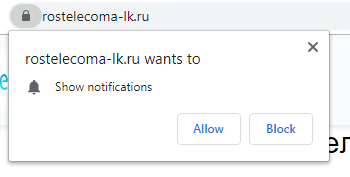

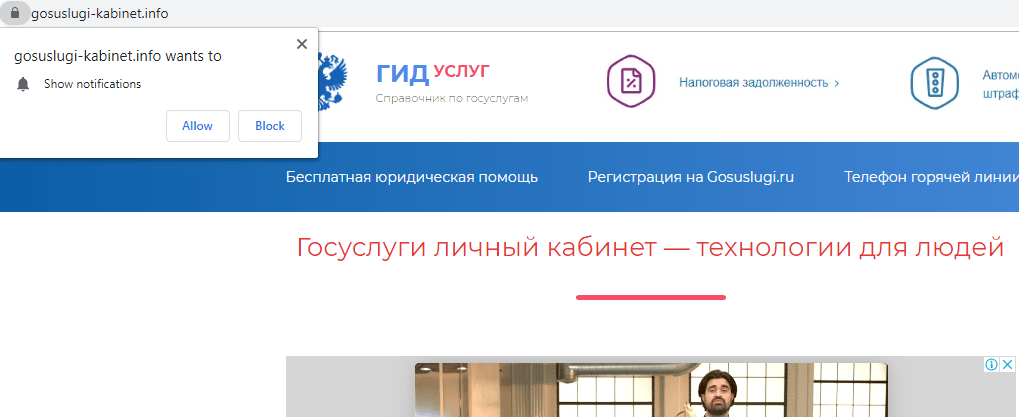

Of particular note are websites touting subscriptions on behalf of popular resources: these are in fact phishing copies of popular websites – of only slightly different appearance and with domain names that look like the real ones.

Sometimes scammers simply modify the script in such a way as to make the buttons swap their places in the subscription request dialog box; if used to clicking on “Block” in the right hand side of the box, chances are this time the user will hit “Allow”.

If you look up the earlier screenshots, you may notice that in this dialog box the buttons are placed the other way around

How do subscriptions work?

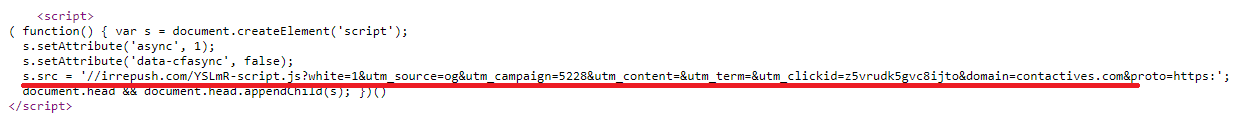

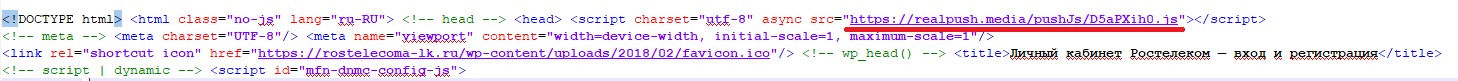

For the user to begin receiving notifications, his or her consent is required. Some requests for consent are illustrated above. These are activated using scripts that come with the webpage.

Examples of webpages featuring links to scripts activating subscription request dialog boxes (marked red)

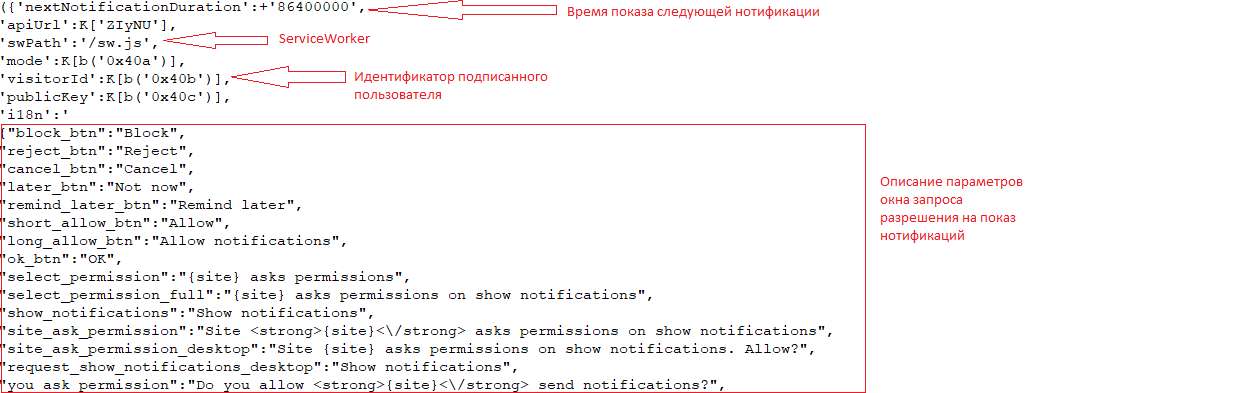

The main purpose of these scripts is to identify the presence of the functions necessary to display notifications. Such as the ServiceWorker script, which operates as a service and allows to push notifications even when the browser is off. The sign-up scripts working with advertisement and scam subscriptions are usually strongly obfuscated. But their key elements are discernable, nevertheless.

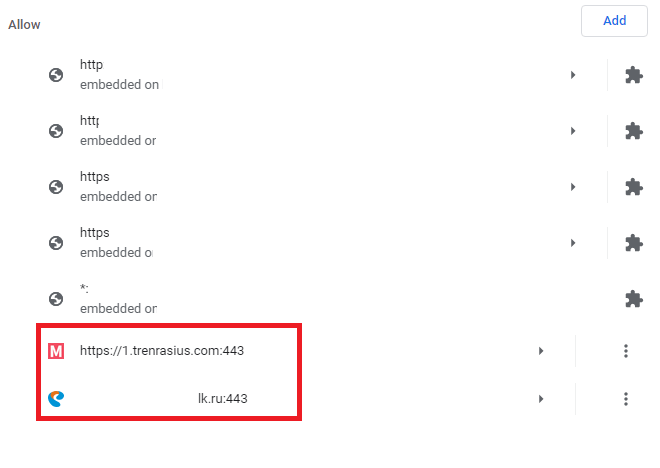

If the user has consented to notifications, the script sends to the notification host server a unique user ID, which will later help to determine who exactly is to receive the news. After consent is secured, the server stores the user’s ID, while a link to the website which has signed the user up for notifications (the page on which the “Allow” button has been clicked) is saved in browser settings.

Websites authorized to deliver push notifications in browser settings. The box highlights ad subscriptions in which the content of notifications is unrelated to the original content of the website

So, the user has consented to notifications, the subscription server has stored the user’s ID, and the browser has memorized the webpage which had provided consent for subscription. Now the server can deliver a push message to the user by sending it via the subscription service in JSON format.

The message contains text, an image (if needed), a link to the destination website, and the user ID. The notification itself will feature a link to the website which had signed the user up, but not the webpage to which the user will be redirected. Very often this misleads the user, especially if the sign-up website uses a domain name made to look like the legitimate one.

What’s the upshot

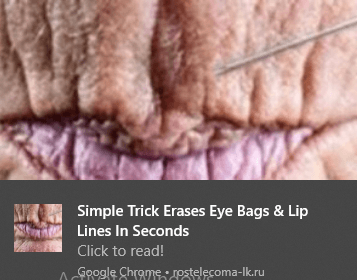

In the most harmless case, the victim will simply receive push ads. Interestingly, their content may vary depending on the user’s location. For example, if in Singapore, country-relevant content will be displayed:

By the way, the example above shows the “success story” advertisement, quite popular ad category in the last couple of years. Push notifications often deliver links to stories about how to get rich or soar to success in the context of sensitive social topics. For example, “how to get rich in a particular country” or “how to become a successful manager if you are a woman”. Most such “tips” advertise success trainings and workshops or various mascots.

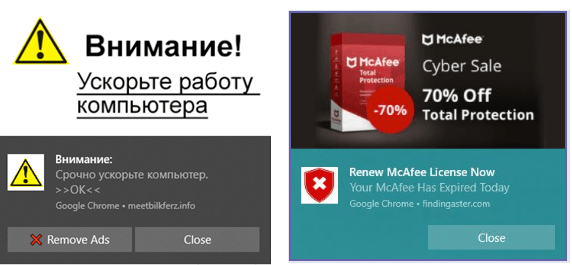

Worthy of separate mention are the push messages disguised as system notifications coming from the OS or applications: the victim may be suggested to click a button to deactivate push ads or to extend the anti-virus license.

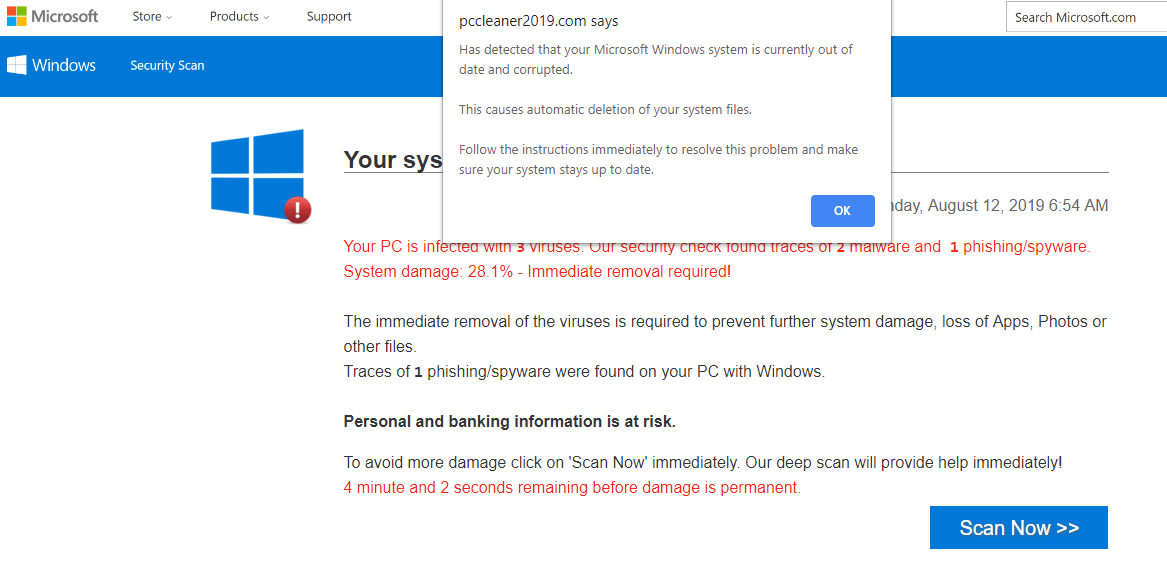

Computer virus infection alert notifications are among the most unpleasant ones. These usually redirect users to pre-designed pages made to appear like the official Microsoft website or resembling some OS Windows components, e.g., Windows Defender:

This trick is often used to distribute various “PC cleaning” utilities. And while some of them do perform the stated functions to a greater or lesser extent, others simply try to milk the user out of as much money as they can – either for the “work” done or for upgrade to a better equipped version.

Avoiding unsolicited subscriptions

To avoid receiving annoying notifications or scam ads, follow a few simple recommendations:

- Where possible, block all subscription offers, unless they come from popular and trusted websites. Even then keep your eyes open not to be taken in by a fake website.

- If unable to avoid an unwanted subscription, you can still block it in the browser settings.

- Use protective solutions made to warn about scam notifications and delete the existing ones, if needed.

Kaspersky Lab’s products detect push notification attempts and existing subscriptions with the verdicts not-a-virus:AdWare.Script.Pusher and Trojan.Multi.BroSubsc.gen.

Unwanted notifications in browser