#TheSAS2017 presentation: Smart Medicine Breaches Its “First Do No Harm” Principle

At last year’s Security Analyst Summit 2017 we predicted that medical networks would be a titbit for cybercriminals. Unfortunately, we were right. The numbers of medical data breaches and leaks are increasing. According to public data, this year is no exception.

For a year we have been observing how cybercriminals encrypt medical data and demand a ransom for it. How they penetrate medical networks and exfiltrate medical information, and how they find medical data on publicly available medical resources.

Opened doors in medical networks

To find a potential entry point into medical infrastructure, we extract the IP ranges of all organizations that have the keywords “medic”, “clinic”, “hospit”, “surgery” and “healthcare” in the organization’s name, then we start the masscan (port scanner) and parse the specialized search engines (like Shodan and Censys) for publicly available resources of these organizations.

Of course, medical perimeters contain a lot of trivial opened ports and services: like web-server, DNS-server, mail-server etc. And you know that’s just the tip of the iceberg. The most interesting part is the non-trivial ports. We left out trivial services, because as we mentioned in our previous article those services are out of date and need to be patched. For example, the web applications of electronic medical records that we found on the perimeters in most cases were out of date.

The most popular ports are the tip of the iceberg. The most interesting part is the non-trivial ports.

Using ZTag tool and Censys, we identify what kinds of services are hidden behind these ports. If you try to look deeper in the embedded tag you will see different stuff: for example printers, SCADA-type systems, NAS etc.

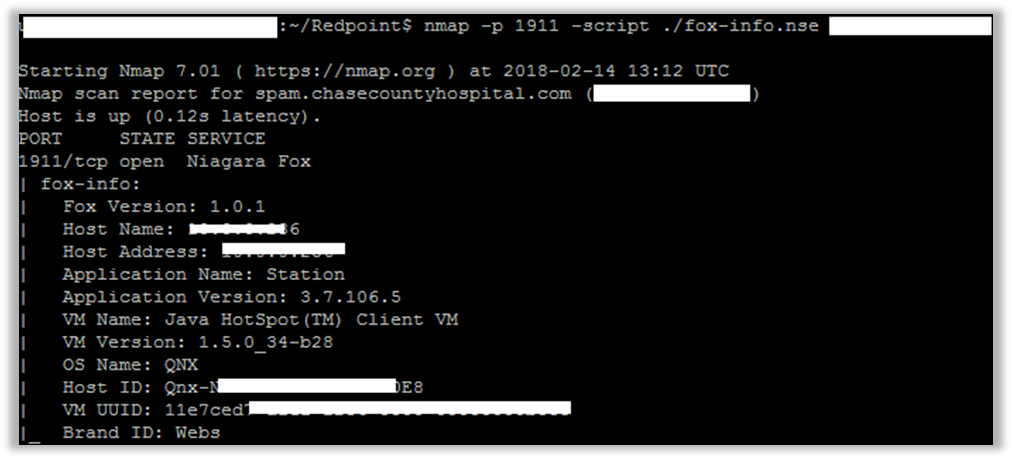

Excluding these trivial things, we found Building Management systems that out of date. Devices using the Niagara Fox protocol usually operate on TCP ports 1911 and 4911. They allow us to gather information remotely from them, such as application name, Java version, host OS, time zone, local IP address, and software versions involved in the stack.

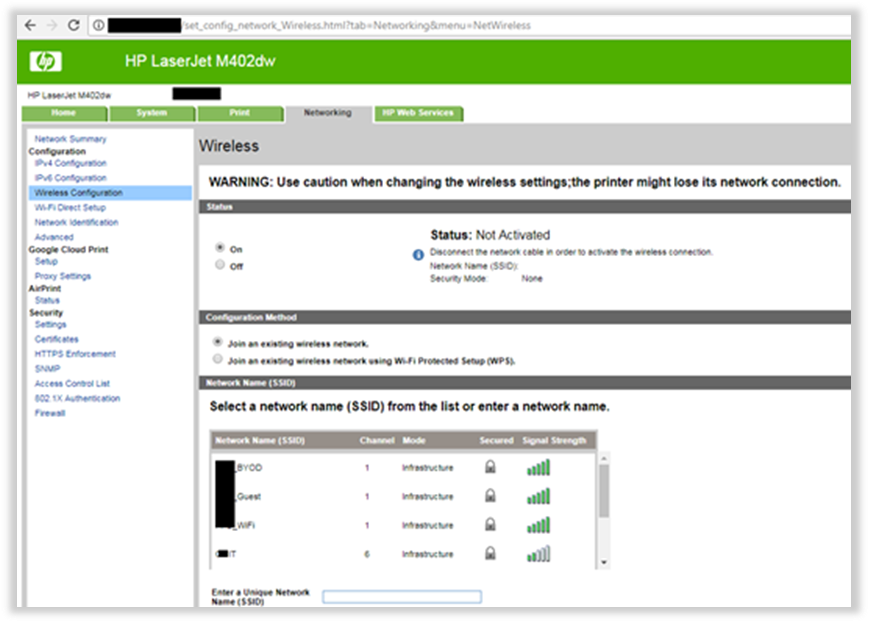

Or printers that have a web interface without an authentication request. The dashboard available online and allows you to get information about internal Wi-Fi networks or, probably, it allows you to get info about documents that appeared in “Job Storage” logs.

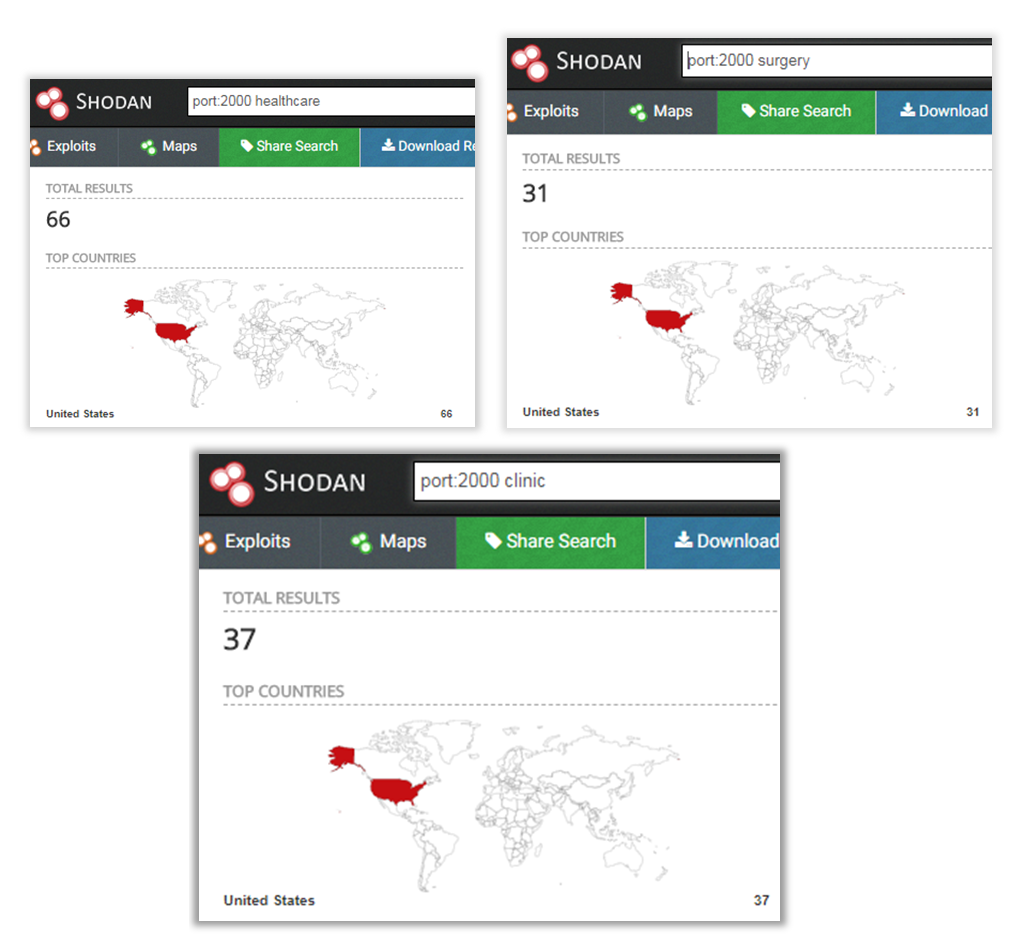

Shodan told us that some medical organizations have an opened port 2000. It’s a smart kettle. We don’t know why, but this model of kettle is very popular in medical organizations. And they have publicly available information about a vulnerability that allows a connection to the kettle to be established using a simple pass and to extract info about the current Wi-Fi connection.

Medical infrastructure has a lot of medical devices, some of them portable. And devices like spirometers or blood pressure monitors support the MQTT protocol to communicate with other devices directly. One of the main components of the MQTT communication – brokers (see here for detailed information about components) are available through the Internet and, as a result, we can find some medical devices online.

Threats that affect medical networks

OK, now we know how they get in. But what’s next? Do they search for personal data, or want to get some money with a ransom or maybe something else? Money? It’s possible… anything is possible. Let’s take a look at some numbers that we collected during 2017.

The statistics are a bit worrying. More than 60% of medical organizations had some kind of malware on their servers or computers. The good news is that if we count something here, it means we’ve deleted malware in the system.

And there’s something even more interesting – organizations closely connected to hospitals, clinics and doctors, i.e. the pharmaceutical industry. Here we see even more attacks. The pharmaceutical industry means “money”, so it’s another titbit for attackers.

Let’s return to our patients. Where are all these attacked hospitals and clinics? Ok, here we the numbers are relative: we divided the number of devices in medical organizations in the country with our AV by the number of devices where we detected malicious code. The TOP 3 were the Philippines, Venezuela and Thailand. Japan, Saudi Arabia and Mexico took the last three spots in the TOP 15.

So the chances of being attacked really depend on how much money the government spends on cybersecurity in the public sector and the level of cybersecurity awareness.

In the pharmaceutical industry we have a completely different picture. First place belongs to Bangladesh. I googled this topic and now the stats look absolutely ok to me. Bangladesh exports meds to Europe. In Morocco big pharma accounts for 14% of GDP. India, too, is in the list, and even some European countries are featured.

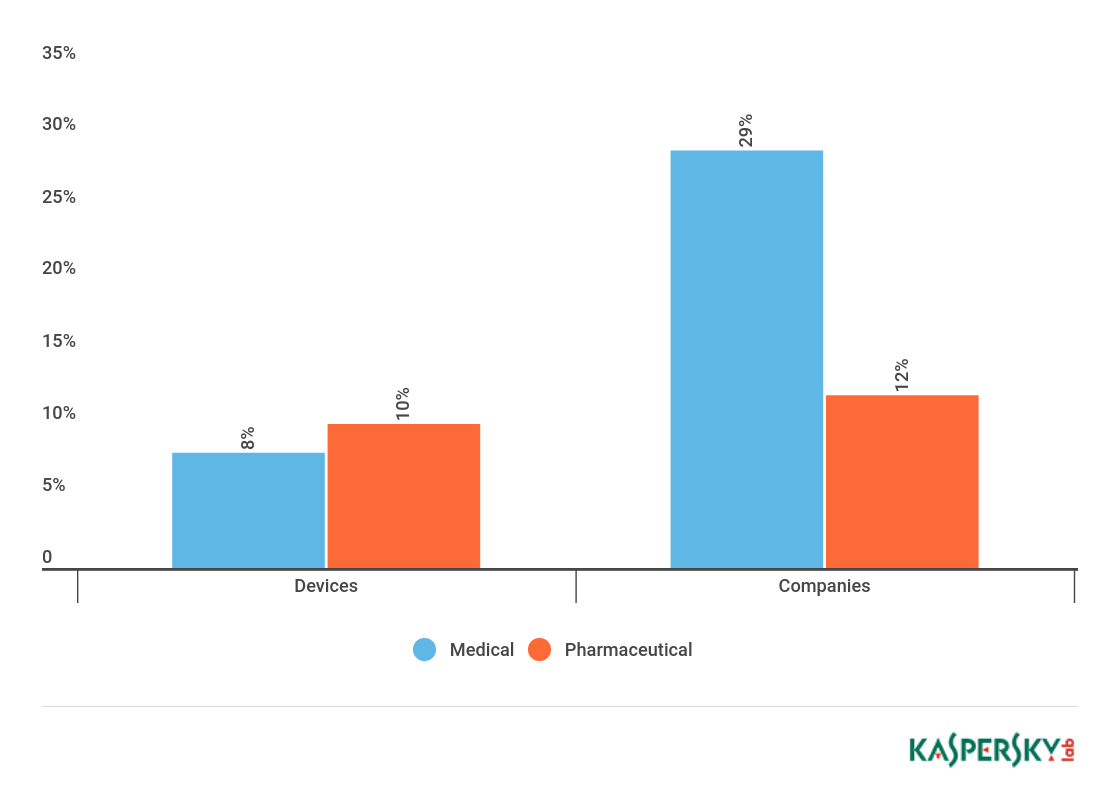

On one in ten devices and in more than 25% of medical and 10% of pharmaceutical companies we detected hacktools: pentesting tools like Mimikatz, Meterpreter, tweaked remote administration kits, and so on.

Which means that either medical organizations are very mature in terms of cybersecurity and perform constant audits of their own infrastructure using red teams and professional pentesters, or, more likely, their networks are infested with hackers.

APT

Our research showed that APT actors are interested in information from pharmaceutical organizations. We were able to identify victims in South East Asia, or more precisely, in Vietnam and Bangladesh. The criminals had targeted servers and used the infamous PlugX malware or Cobalt Strike to exfiltrate data.

PlugX RAT, used by Chinese-speaking APT actors, allows criminals to perform various malicious operations on a system without the user’s knowledge or authorization, including but not limited to copying and modifying files, logging keystrokes, stealing passwords and capturing screenshots of user activity. PlugX, as well as Cobalt Strike, is used by cybercriminals to discreetly steal and collect sensitive or profitable information. During our research we were unable to track the initial attack vectors, but there are signs that they could be attacks exploiting vulnerable software on servers.

Taking into account the fact that hackers placed their implants on the servers of pharmaceutical companies, we can assume they are after intellectual property or business plans.

How to live with it

- Remove all nodes that process medical data from public

- Periodically update your installed software and remove unwanted applications

- Refrain from connecting expensive equipment to the main LAN of your organization

More tips at “Connected Medicine and Its Diagnosis“.

Time of death? A therapeutic postmortem of connected medicine

Michael McCarty

The talk about medical networks, what about remote home monitoring systems for pacemaker implants.Yes fairly new technology, a diagnostic tool for the doctors, as well as data information for manufacturers. And hopefully it would save patient’s lives as well. The vulnerability of ones medical records, would be no different than a pacemaker being hacked.But then again there’s alway a third party embedded somewhere has we move forward in advancements in medical technology.