In early February this year, Belgian police seized the C&C servers of the infamous Cryakl cryptor. Soon afterwards, they handed over the private keys to our experts, who used them to update the free RakhniDecryptor tool for recovering files encrypted by the malware. The ransomware, which for years had raged across Russia (and elsewhere through partners), was finally stopped.

For Kaspersky Lab, this victory was the culmination of more than three years of monitoring Cryakl and studying its various modifications — a major effort that eventually defeated the cybercriminals. This story clearly illustrates how cooperation can, in the end, get the better of any crooked scheme.

This spring marked the fourth anniversary of the malware’s first attacks. Against the backdrop of a general decline in ransomware activity (see our report), we decided to return to the topic of Cryakl and tell in detail about how one of the most eye-catching members of this endangered species evolved.

Propagation methods

We first encountered Cryakl (without knowing what it was exactly) in the spring of 2014. The malware had just begun to spread actively, mainly through spam mailings. Initially, attachments with the malware were found in emails allegedly from the Supreme Arbitration Court of the Russian Federation in connection with various offenses. But it wasn’t long before messages started arriving from other organizations too, in particular homeowner associations.

A typical malicious email contained an attachment of one of the following types:

- Office document with a malicious macro

- JS script loading a Trojan

- PDF document with a link to an executable

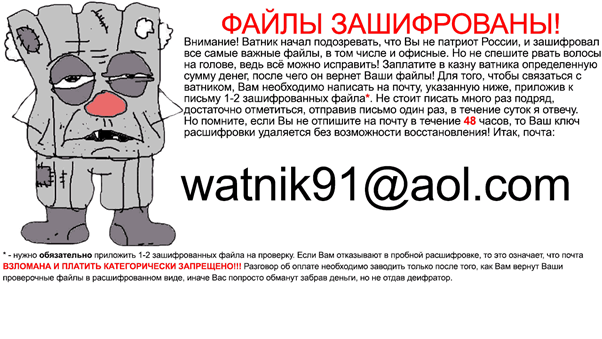

It was around this time that the malware acquired its nickname: after encrypting files on the user’s hard drive, one of the Cryakl variants (Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Cryakl.bo) changed the desktop wallpaper to a picture of Fantomas, the villain from the 1964 French film of the same name.

Later, in 2016, we discovered an interesting modification of the ransomware with a rather cunning mode of distribution. Today, an attack using specialized third-party software would raise few eyebrows, but it was not par for the course in 2016, when Fantomas was distributed as a script for a popular Russian accounting program and a business process management tool. The approach was indeed sneaky: employees were sent a message with a request to “update the bank classifier,” whereupon they opened the attached executable file.

Neither was the attack vector surprising, since Cryakl mainly targeted users in Russia and most of the ransom demands were written in Russian. However, further research showed that the cybercriminals who distributed Fantomas did not limit themselves to the Russian market.

In 2016, we observed the growing complexity and variety of ransomware cryptors, including the emergence of ready-made solutions such as Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) for those lacking skills, resources, or time to create their own. Such services were circulated through an expanding and increasingly influential underground ecosystem.

This was the business model chosen by Cryakl’s creators: “partners” were invited to purchase the build of the malware to attack users in other regions, allowing its authors to monetize the product for a second time.

Statistics

In expanding its infrastructure, Cryakl also widened its attack geography. From the first infection until today, more than 50,000 people in Russia—plus thousands more in Japan, Italy, and Germany — suffered at the evil hands of Fantomas.

Data on Cryakl activity over the years shows that the first signs of life appeared in 2014.

At around the time when the RaaS distribution model was deployed, Fantomas was on the rampage, increasing its attacks more than sixfold.

Distinguishing features

Despite the number and variety of modifications, the use of “partners,” and its long history, the malware cannot be said to have undergone any significant changes — the differences between the various versions was slight. This makes it possible to identify the main features of Fantomas.

Cryakl is written in Delphi, but very amateurishly. This immediately jumped out when we took a look at one of the first versions. The file operations were extremely ineffective, and the encryption algorithm was elementary and not secure. We even thought we were dealing with a test build (especially since the internal version was designated 0.0.0.0). The overall impression was that Cryakl’s authors were not the most experienced virus writers. Recall that it all started with mailings about military conscription.

The first detected version of the malware did not change the names of the encrypted files, but placed a text structure at the end of each file with the MD5 of the header, the MD5 of the file itself, its original size, offsets, and the sizes of a few encrypted snippets. It ended with the tag {CRYPTENDBLACKDC}, required to distinguish encrypted files from unencrypted ones.

Through continued observations over the following months, we regularly discovered ever newer versions of Cryakl: 1.0.0.0, 2.x.0.0, 3.x.0.0, …, 8.0.0.0. Different versions increasingly modified the encryption algorithm as well as the file naming scheme (extensions started to appear of the type: id-{….08.2014 16@02@275587800}-email-mserbinov@aol.com-ver-4.0.0.0.cbf). The text structure at the end of the file changed multiple times, and new encryption and decryption data as well as various service information were added to it.

After that, we found the Cryakl version CL 0.0.0.0 (not to be confused with 0.0.0.0), which had notable changes from previous modifications: besides encrypting parts of the file with a “homebrew” symmetric algorithm, for unknown reasons the Trojan now encrypted other parts with the RSA algorithm. Another marked change was the sending of key data used in the encryption to the attackers’ C&C servers. The structure at the end of the encrypted file was framed with new tags ({ENCRYPTSTART}, {ENCRYPTENDED}), required to determine the encrypted files.

In version CL 1.0.0.0, the Trojan stopped sending keys via the Internet. Instead, data required for decryption was now encrypted with RSA and placed in the structure at the end of the file.

Nothing changed fundamentally in the subsequent versions CL 1.1.0.0 – CL 1.2.0.0, only the size of the RSA keys increased. This enhanced the overall level of encryption, but did not change the situation radically.

Starting with version CL 1.3.0.0, the Trojan (again for unknown reasons) stopped encrypting file regions with RSA. The algorithm was used only to encrypt keys, while file contents were processed by the slightly modified “homebrew” symmetric algorithm.

In all versions of the malware, the cybercriminals left various email addresses for communication purposes. These addresses are contained in the names of encrypted files (for example, email-eugene_danilov@yahoo.com.ver-CL 1.3.1.0.id-….randomname-FFIMEFJCNGATTMVPFKEXCVPICLUDXG.JGZ.lfl) and in the image set by the Trojan as the desktop wallpaper. Victims received reply emails containing a ransom sum in Bitcoin and a cryptocurrency wallet address to make the payment.

On receiving the funds, the cybercriminals sent the victim a decryptor tool and a key file.

The terms of payment varied: for example, the above-mentioned Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Cryakl.bo set a deadline of 48 hours. Moreover, the cybercriminals did not immediately say how much they wanted in return for their “help,” specifying the cost of the decryptor only in their reply emails. It’s not ruled out that the sum depended on the number and quality of encrypted files. For example, in one case of infection, the cybercriminals demanded $1000. Before doing so, according to victims, they connected to the infected computer and deleted all backup copies on it.

Fantomas is slain

The problem with Cryakl was that its newest versions employed asymmetric RSA encryption. The malware body contained public keys used to encrypt user data. Without knowledge of the corresponding private keys, we could not develop a decryption tool. The keys seized and handed over by the Belgian police enabled us to decipher several versions of the ransomware.

The keys made it possible to reengineer the RakhniDecryptor tool to decrypt files encrypted with the following versions of Cryakl:

| Trojan version | Cybercriminals’ email |

| CL 1.0.0.0 | cryptolocker@aol.com iizomer@aol.com seven_Legion2@aol.com oduvansh@aol.com ivanivanov34@aol.com trojanencoder@aol.com load180@aol.com moshiax@aol.com vpupkin3@aol.com watnik91@aol.com |

| CL 1.0.0.0.u | cryptolocker@aol.com_graf1 cryptolocker@aol.com_mod byaki_buki@aol.com_mod2 |

| CL 1.2.0.0 | oduvansh@aol.com cryptolocker@aol.com |

| CL 1.3.0.0 | cryptolocker@aol.com |

| CL 1.3.1.0 | byaki_buki@aol.com byaki_buki@aol.com_grafdrkula@gmail.com vpupkin3@aol.com |

The return of Fantomas, or how we deciphered Cryakl