Here’s a link to the full paper (part 1) about our Red October research. During the next days, we’ll be publishing Part 2, which contains a detailed technical analysis of all the known modules. Please stay tuned.

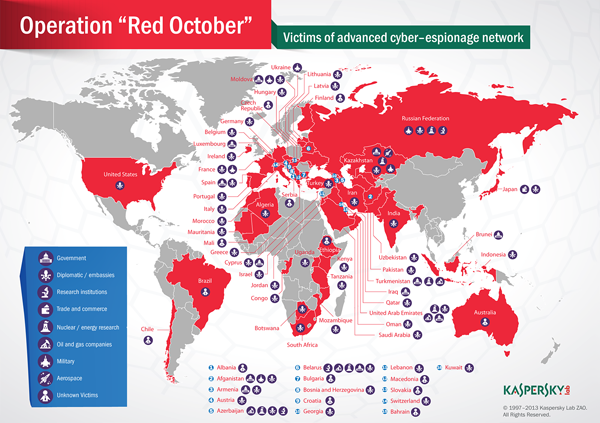

During the past five years, a high-level cyber-espionage campaign has successfully infiltrated computer networks at diplomatic, governmental and scientific research organizations, gathering data and intelligence from mobile devices, computer systems and network equipment.

Kaspersky Lab’s researchers have spent several months analyzing this malware, which targets specific organizations mostly in Eastern Europe, former USSR members and countries in Central Asia, but also in Western Europe and North America.

The campaign, identified as “Rocra”, short for “Red October”, is currently still active with data being sent to multiple command-and-control servers, through a configuration which rivals in complexity the infrastructure of the Flame malware. Registration data used for the purchase of C&C domain names and PE timestamps from collected executables suggest that these attacks date as far back as May 2007.

Some key findings from our investigation:

- The attackers have been active for at least five years, focusing on diplomatic and governmental agencies of various countries across the world. Information harvested from infected networks is reused in later attacks. For example, stolen credentials were compiled in a list and used when the attackers needed to guess passwords and network credentials in other locations. To control the network of infected machines, the attackers created more than 60 domain names and several server hosting locations in different countries (mainly Germany and Russia). The C&C infrastructure is actually a chain of servers working as proxies and hiding the location of the true -mothership- command and control server.

- The attackers created a multi-functional framework which is capable of applying quick extension of the features that gather intelligence. The system is resistant to C&C server takeover and allows the attacker to recover access to infected machines using alternative communication channels.

- Beside traditional attack targets (workstations), the system is capable of stealing data from mobile devices, such as smartphones (iPhone, Nokia, Windows Mobile); dumping enterprise network equipment configuration (Cisco); hijacking files from removable disk drives (including already deleted files via a custom file recovery procedure); stealing e-mail databases from local Outlook storage or remote POP/IMAP server; and siphoning files from local network FTP servers.

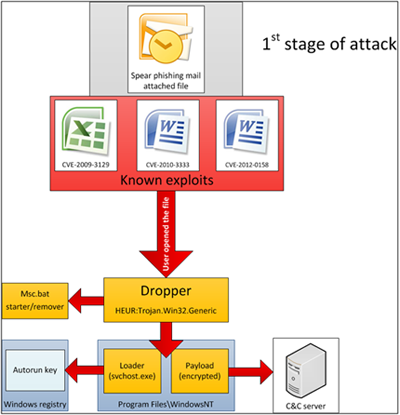

- We have observed the use of at least three different exploits for previously known vulnerabilities: CVE-2009-3129 (MS Excel), CVE-2010-3333 (MS Word) and CVE-2012-0158 (MS Word). The earliest known attacks used the exploit for MS Excel and took place in 2010 and 2011, while attacks targeting the MS Word vulnerabilities appeared in the summer of 2012.

- The exploits from the documents used in spear phishing were created by other attackers and employed during different cyber attacks against Tibetan activists as well as military and energy sector targets in Asia. The only thing that was changed is the executable which was embedded in the document; the attackers replaced it with their own code.

Sample fake image used in one of the Rocra spear phishing attacks.

- During lateral movement in a victim’s network, the attackers deploy a module to actively scan the local area network, find hosts vulnerable for MS08-067 (the vulnerability exploited by Conficker) or accessible with admin credentials from its own password database. Another module used collected information to infect remote hosts in the same network.

- Based on registration data of the C&C servers and numerous artifacts left in executables of the malware, we strongly believe that the attackers have Russian-speaking origins. Current attackers and executables developed by them have been unknown until recently, they have never related to any other targeted cyber attacks. Notably, one of the commands in the Trojan dropper switches the codepage of an infected machine to 1251 before installation. This is required to address files and directories that contain Cyrillic characters in their names.

Rocra FAQ:

What is Rocra? Where does the name come from? Was Operation Rocra targeting any specific industries, organizations or geographical regions?

Rocra (short for “Red October”) is a targeted attack campaign that has been going on for at least five years. It has infected hundreds of victims around the world in eight main categories:

- Government

- Diplomatic / embassies

- Research institutions

- Trade and commerce

- Nuclear / energy research

- Oil and gas companies

- Aerospace

- Military

It is quite possible there are other targeted sectors which haven’t been discovered yet or have been attacked in the past.

How and when was it discovered?

We have come by the Rocra attacks in October 2012, at the request of one of our partners. By analysing the attack, the spear phishing and malware modules, we understood the scale of this campaign and started dissecting it in depth.

Who provided you with the samples?

Our partner who originally pointed us to this malware prefers to remain anonymous.

How many infected computers have been identified by Kaspersky Lab? How many victims are there? What is the estimated size of Operation Red October on a global scale?

During the past months, we’ve counted several hundreds of infections worldwide – all of them in top locations such as government networks and diplomatic institutions. The infections we’ve identified are distributed mostly in Eastern Europe, but there are also reports coming from North America and Western European countries such as Switzerland or Luxembourg.

Based on our Kaspersky Security Network (KSN) here’s a list of countries with most infections (only for those with more than 5 victims):

Country |

Infections |

|---|---|

| RUSSIAN FEDERATION | 35 |

| KAZAKHSTAN | 21 |

| AZERBAIJAN | 15 |

| BELGIUM | 15 |

| INDIA | 14 |

| AFGHANISTAN | 10 |

| ARMENIA | 10 |

| IRAN; ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF | 7 |

| TURKMENISTAN | 7 |

| UKRAINE | 6 |

| UNITED STATES | 6 |

| VIET NAM | 6 |

| BELARUS | 5 |

| GREECE | 5 |

| ITALY | 5 |

| MOROCCO | 5 |

| PAKISTAN | 5 |

| SWITZERLAND | 5 |

| UGANDA | 5 |

| UNITED ARAB EMIRATES | 5 |

For the sinkhole statistics see below.

Who is behind/responsible for this operation? Is this a nation-state sponsored attack?

The information we have collected so far does not appear to point towards any specific location, however, two important factors stand out:

- The exploits appear to have been created by Chinese hackers.

- The Rocra malware modules have been created by Russian-speaking operatives.

Currently, there is no evidence linking this with a nation-state sponsored attack. The information stolen by the attackers is obviously of the highest level and includes geopolitical data which can be used by nation states. Such information could be traded in the underground and sold to the highest bidder, which can be of course, anywhere.

Are there any interesting texts in the malware that can suggest who the attackers are?

Several Rocra modules contain interesting typos and mis-spellings:

- network_scanner: “SUCCESSED”, “Error_massage”, “natrive_os”, “natrive_lan”

- imapispool: “UNLNOWN_PC_NAME”, “WinMain: error CreateThred stop”

- mapi_client: “Default Messanger”, “BUFEER IS FULL”

- msoffice_plugin: “my_encode my_dencode”

- winmobile: “Zakladka injected”, “Cannot inject zakladka, Error: %u”

- PswSuperMailRu: “——-PROGA START—–“, “——-PROGA END—–“

The word “PROGA” used in here might refer to transliteration of Russian slang “ПРОГА”, which literally means an application or a program among Russian-speaking software engineers.

In particular, the word “Zakladka” in Russian can mean:

- “bookmark”

- (more likely) a slang term meaning “undeclared functionality”, i.e. in software or hardware. However, it may also mean a microphone embedded in a brick of the embassy building.

The C++ class that holds the C&C configuration parameters is called “MPTraitor” and the corresponding configuration section in the resources is called “conn_a”. Some examples include:

- conn_a.D_CONN

- conn_a.J_CONN

- conn_a.D_CONN

- conn_a.J_CONN

What kind of information is being hijacked from infected machines?

Information stolen from infected systems includes documents with extensions:

cif, key, crt, cer, hse, pgp, gpg, xia, xiu, xis, xio, xig, acidcsa, acidsca,

aciddsk, acidpvr, acidppr, acidssa.

In particular, the “acid*” extensions appear to refer to the classified software “Acid Cryptofiler”, which is used by several entities such as the European Union and/or NATO.

What is the purpose/objective of this operation? What were the attackers looking for by conducting this sustained cyber-espionage campaign for so many years?

The main purpose of the operation appears to be the gathering of classified information and geopolitical intelligence, although it seems that the information gathering scope is quite wide. During the past five years, the attackers collected information from hundreds of high profile victims although it’s unknown how the information was used.

It is possible that the information was sold on the black market, or used directly.

What are the infection mechanisms for the malware? Does it have self-propagating (worm) capabilities? How does it work? Do the attackers have a customized attack platform?

The main malware body acts as a point of entry into the system which can later download modules used for lateral movement. After initial infection, the malware won’t propagate by itself – typically, the attackers would gather information about the network for a few days, identify key systems and then deploy modules which can compromise other computers in the network, for instance by using the MS08-067 exploit.

In general, the Rocra framework is designed for executing “tasks” that are provided by its C&C servers. Most of the tasks are provided as one-time PE DLL libraries that are received from the server, executed in memory and then immediately discarded.

Several tasks however need to be constantly present in the system, i.e. waiting for the iPhone or Nokia mobile to connect. These tasks are provided as PE EXE files and are installed in the infected machine.

Examples of “persistent” tasks

- Once a USB drive is connected, search and extract files by mask/format, including deleted files. Deleted files are restored using a built in file system parser

- Wait for an iPhone or a Nokia phone to be connected. Once connected, retrieve information about the phone, its phone book, contact list, call history, calendar, SMS messages, browsing history

- Wait for a Windows Mobile phone to be connected. Once connected, infect the phone with a mobile version of the Rocra main component

- Wait for a specially crafted Microsoft Office or PDF document and execute a malicious payload embedded in that document, implementing a one-way covert channel of communication that can be used to restore control of the infected machine

- Record all the keystrokes, make screenshots

- Execute additional encrypted modules according to a pre-defined schedule

- Retrieve e-mail messages and attachments from Microsoft Outlook and from reachable mail servers using previously obtained credentials

Examples of “one-time” tasks

- Collect general software and hardware environment information

- Collect filesystem and network share information, build directory listings, search and retrieve files by mask provided by the C&C server

- Collect information about installed software, most notably Oracle DB, RAdmin, IM software including Mail.Ru agent, drivers and software for Windows Mobile, Nokia, SonyEricsson, HTC, Android phones, USB drives

- Extract browsing history from Chrome, Firefox, Internet Explorer, Opera

- Extract saved passwords for Web sites, FTP servers, mail and IM accounts

- Extract Windows account hashes, most likely for offline cracking

- Extract Outlook account information

- Determine the external IP address of the infected machine

- Download files from FTP servers that are reachable from the infected machine (including those that are connected to its local network) using previously obtained credentials

- Write and/or execute arbitrary code provided within the task

- Perform a network scan, dump configuration data from Cisco devices if available

- Perform a network scan within a predefined range and replicate to vulnerable machines using the MS08-067 vulnerability

- Replicate via network using previously obtained administrative credentials

The Rocra framework was designed by the attackers from scratch and hasn’t been used in any other operations.

Was the malware limited to only workstations or did it have additional capabilities, such as a mobile malware component?

Several mobile modules exist, which are designed to steal data from several types of devices:

- Windows Mobile

- iPhone

- Nokia

These modules are installed in the system and wait for mobile devices to be connected to the victim’s machine. When a connection is detected, the modules start collecting data from the mobile phones.

How many variants, modules or malicious files were identified during the overall duration of Operation Red October?

During our investigation, we’ve uncovered over 1000 modules belonging to 30 different module categories. These have been created between 2007 with the most recent being compiled on 8th Jan 2013.

Here’s a list of known modules and categories:

Were initial attacks launched at select “high-profile” victims or were they launched in series of larger (wave) attacks at organizations/victims?

All the attacks are carefully tuned to the specifics of the victims. For instance, the initial documents are customized to make them more appealing and every single module is specifically compiled for the victim with a unique victim ID inside.

Later, there is a high degree of interaction between the attackers and the victim – the operation is driven by the kind of configuration the victim has, which type of documents the use, installed software, native language and so on.

Compared to Flame and Gauss, which are highly automated cyberespionage campaigns, Rocra is a lot more “personal” and finely tuned for the victims.

Is Rocra related in any way to the Duqu, Flame and Gauss malware?

Simply put, we could not find any connections between Rocra and the Flame / Tilded platforms.

How does Operation Rocra compare to similar campaigns such as Aurora and Night Dragon? Any notable similarities or differences?

Compared to Aurora and Night Dragon, Rocra is a lot more sophisticated. During our investigation we’ve uncovered over 1000 unique files, belonging to about 30 different module categories. Generally speaking, the Aurora and Night Dragon campaigns used relatively simple malware to steal confidential information.

With Rocra, the attackers managed to stay in the game for over 5 years and evade detection of most antivirus products while continuing to exfiltrate what must be hundreds of Terabytes by now.

How many Command & Control servers are there? Did Kaspersky Lab conduct any forensic analysis on them?

During our investigation, we uncovered more than 60 domain names used by the attackers to control and retrieve data from the victims. The domain names map to several dozen IPs located mostly in Russia and Germany.

Here’s an overview of the Rocra’s command and control infrastructure, as we believe it looks from our investigations:

More detailed information about the Command and Control servers will be revealed at a later date.

Did you sinkhole any of the Command & Control servers?

We were able to sinkhole six of the over 60 domains used by the various versions of the malware. During the monitoring period (2 Nov 2012 – 10 Jan 2013), we registered over 55,000 connections to the sinkhole. The number of different IPs connecting to the sinkhole was 250.

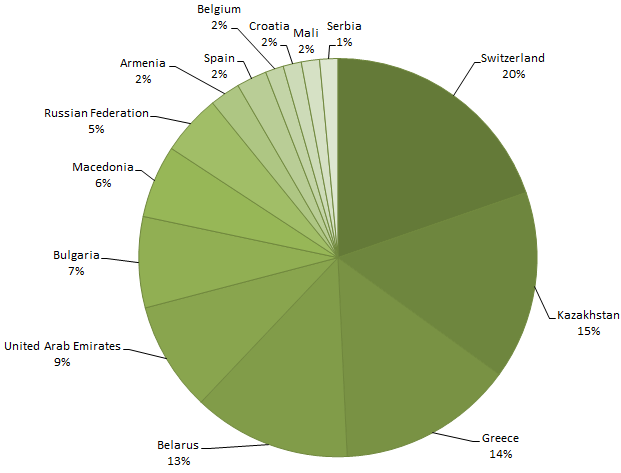

From the point of view of country distribution of connections to the sinkhole, we have observed victims in 39 countries, with most of IPs being from Switzerland. Kazakhstan and Greece follow next.

Sinkhole statistics – 2 Nov 2012 – 10 Jan 2013

Is Kaspersky Lab working with any governmental organizations, Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERTs), law enforcement agencies or security companies as part of the investigation and disinfection efforts?

Kaspersky Lab, in collaboration with international organizations, Law Enforcement, Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERTs) and other IT security companies is continuing its investigation of Operation Red October by providing technical expertise and resources for remediation and mitigation procedures.

Kaspersky Lab would like to express their thanks to: US-CERT, the Romanian CERT and the Belarusian CERT for their assistance with the investigation.

If you are a CERT and would like more information about infections in your country, please contact us at theflame@kaspersky.com.

Here’s a link to the full paper (part 1) about our Red October research. During the next days, we’ll be publishing Part 2, which contains a detailed technical analysis of all the known modules. Please stay tuned.

A list of MD5s of known documents used in the Red October attacks:

1f86299628bed519718478739b0e4b0c

2672fbba23bf4f5e139b10cacc837e9f

350c170870e42dce1715a188ca20d73b

396d9e339c1fd2e787d885a688d5c646

3ded9a0dd566215f04e05340ccf20e0c

44e70bce66cdac5dc06d5c0d6780ba45

4bfa449f1a351210d3c5b03ac2bd18b1

4ce5fd18b1d3f551a098bb26d8347ffb

4daa2e7d3ac1a5c6b81a92f4a9ac21f1

50bd553568422cf547539dd1f49dd80d

51edea56c1e83bcbc9f873168e2370af

5d1121eac9021b5b01570fb58e7d4622

5ecec03853616e13475ac20a0ef987b6

5f9b7a70ca665a54f8879a6a16f6adde

639760784b3e26c1fe619e5df7d0f674

65d277af039004146061ff01bb757a8f

6b23732895daaad4bd6eae1d0b0fef08

731c68d2335e60107df2f5af18b9f4c9

7e5d9b496306b558ba04e5a4c5638f9f

82e518fb3a6749903c8dc17287cebbf8

85baebed3d22fa63ce91ffafcd7cc991

91ebc2b587a14ec914dd74f4cfb8dd0f

93d0222c8c7b57d38931cfd712523c67

9950a027191c4930909ca23608d464cc

9b55887b3e0c7f1e41d1abdc32667a93

9f470a4b0f9827d0d3ae463f44b227db

a7330ce1b0f89ac157e335da825b22c7

b9238737d22a059ff8da903fbc69c352

c78253aefcb35f94acc63585d7bfb176

fc3c874bdaedf731439bbe28fc2e6bbe

bb2f6240402f765a9d0d650b79cd2560

bd05475a538c996cd6cafe72f3a98fae

c42627a677e0a6244b84aa977fbea15d

cb51ef3e541e060f0c56ac10adef37c3

ceac9d75b8920323477e8a4acdae2803

cee7bd726bc57e601c85203c5767293c

d71a9d26d4bb3b0ed189c79cd24d179a

d98378db4016404ac558f9733e906b2b

dc4a977eaa2b62ad7785b46b40c61281

dc8f0d4ecda437c3f870cd17d010a3f6

de56229f497bf51274280ef84277ea54

ec98640c401e296a76ab7f213164ef8c

f0357f969fbaf798095b43c9e7a0cfa7

f16785fc3650490604ab635303e61de2

The “Red October” Campaign – An Advanced Cyber Espionage Network Targeting Diplomatic and Government Agencies