Over the past few weeks, we have been busy researching the Command and Control infrastructure used by Duqu.

It is now a well-known fact that the original Duqu samples were using a C&C server in India, located at an ISP called Webwerks. Since then, another Duqu C&C server has been discovered which was hosted on a server at Combell Group Nv, in Belgium.

At Kaspersky Lab we have currently cataloged and identified over 12 different Duqu variants. These connect to the C&C server in India, to the one in Belgium, but also to other C&C servers, notably two servers in Vietnam and one in the Netherlands. Besides these, many other servers were used as part of the infrastructure, some of them used as main C&C proxies while others were used by the attackers to jump around the world and make tracing more difficult. Overall, we estimate there have been more than a dozen Duqu command and control servers active during the past three years.

Before going any further, let us say that we still do not know who is behind Duqu and Stuxnet. Although we have analyzed some of the servers, the attackers have covered their tracks quite effectively. On 20 October 2011 a major cleanup operation of the Duqu network was initiated. The attackers wiped every single server they had used as far back as 2009 – in India, Vietnam, Germany, the UK and so on. Nevertheless, despite the massive cleanup, we can shed some light on how the C&C network worked.

Server ‘A’ – Vietnam

Server ‘A’ was located in Vietnam and was used to control certain Duqu variants found in Iran. This was a Linux server running CentOS 5.5. Actually, all the Duqu C&C servers we have found so far run CentOS – version 5.4, 5.5 or 5.2. It is not known if this is just a coincidence or if the attackers have an affinity (exploit?) for CentOS 5.x.

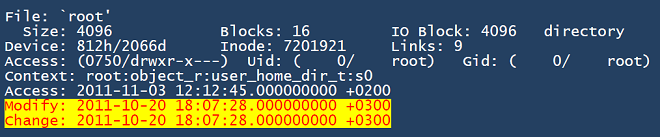

When we began analyzing the server image, we first noticed that at least the ‘root’ folder and the system log files folder ‘/var/log/’ had a ‘last modified’ timestamp of 2011-10-20 18:07:28 (UTC+3).

However, both folders were almost empty. Despite the modification date/time of the root folder, there were no files inside modified even close to this date. This indicates that certain operations (probably deletions / cleaning) took place on 20 October at around 18:07:28 GMT+3 (22:07:28 Hanoi time).

Interestingly, on Linux it is sometimes possible to recover deleted files; however, in this case we couldn’t find anything. No matter how hard we searched, the sectors where the files should have been located were empty and full of zeroes.

By bruteforce scanning the slack (unused) space in the ‘/’ partition, we were able to recover parts of the ‘sshd.log’ file. This was kind of unexpected and it is an excellent lesson about Linux and the ext3 file system internals; deleting a file doesn’t mean there are no traces or parts, sometimes from the past. The reason for this is that Linux constantly reallocates commonly used files to reduce fragmentation. Hence, it is possible to find parts of older versions of a certain file, even if they were thoroughly deleted.

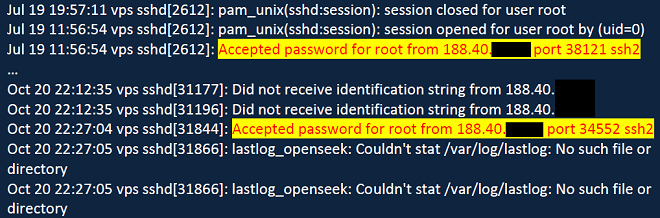

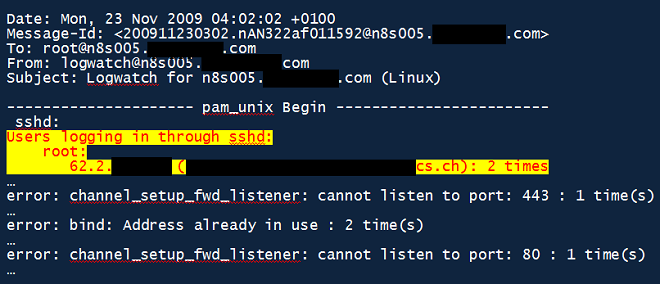

As can be seen from the log above, the root user logged in twice from the same IP address on 19 July and 20 October. The latter login is quite close to the last modified timestamps on the root folder, which indicates this was the person responsible for the system cleanup – bingo!

So, what exactly was this server doing? We were unable to answer this question until we analyzed server ‘B’ (see below). However, we did find something really interesting. On 15 February 2011 openssh-5.8p1 (the sourcecode) was copied to the machine and subsequently installed. The distribution is “openssh_5.8p1-4ubuntu1.debian.tar.gz” with an MD5 of ‘86f5e1c23b4c4845f23b9b7b493fb53d’ (stock distribution). We can assume the machine has been running openssh-4.3p1 as included in the original distribution of CentOS 5.2. On 19 July 2011 OpenSSH 5.8p2 was copied to the system. It was compiled and binaries were installed into folders (/usr/local/sbin). The OpenSSH distribution was again the stock one.

The date of 19 July is important because it indicates when the new OpenSSH 5.8p2 was compiled in the system. Just after that, the attackers logged in, probably to check if everything was OK.

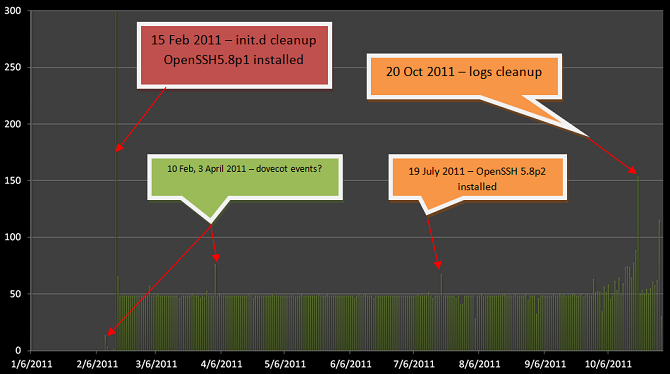

One good way of looking at the server is to check the file deletions and to put them into an activity graph. On days when there was notable operations going on, you see a spike:

For our particular server, several spikes immediately raise suspicions: 15 February and 19 July, when new versions of OpenSSH were installed; 20 October, when the server cleanup took place. Additionally, we found spikes on 10 February and 3 April, when certain events took place. We were able to identify “dovecot” crashes on these dates, although we can’t be sure they were caused by the attackers (“dovecot” remote exploit?) or simply instabilities.

Of course, for server ‘A’, three big questions remain:

- How did the attackers get access to this computer in the first place?

- What exactly was its purpose and how was it (ab-)used?

- Why did the attackers replace the stock OpenSSH 4.3 with version 5.8?

We will answer some of these at the end.

Server ‘B’ – Germany

This server was located at a data center in Germany that belongs to a Bulgarian hosting company. It was used by the attackers to log in to the Vietnamese C&C. Evidence also seems to indicate it was used as a Duqu C&C in the distant past, although we couldn’t determine the exact Duqu variant which did so.

Just like the server in Vietnam, this one was thoroughly cleaned on 20 October 2011. The “root” folder and the “etc” folder have timestamps from this date, once again pointing to file deletions / modifications on this date. Immediately after cleaning up the server, the attackers rebooted it and logged in again to make sure all evidence and traces were erased.

Once again, by scanning the slack (unused) space in the ‘/’ partition, we were able to recover parts of the ‘sshd.log’ file. Here are the relevant entries:

First of all, about the date – 18 November. Unfortunately, “sshd.log” doesn’t contain the year. So, we can’t know for sure if this was 2010 or 2009 (we do know it was NOT 2011) from this information alone. We were, however, able to find another log file which indicates that the date was 2009:

What you can see above is a fragment of a “logwatch” entry which indicates the date of breach to be 23 November 2009, when the root user logged in from the IP address from 19 November, in the “sshd.log”. The other two messages are also important – they are errors from “sshd” indicating a port 80 and port 443 redirection was attempted; however, they were already busy. So now we know how these servers were used as C&C – port 80 and port 443 were redirected over sshd to the attackers’ server. These Duqu C&C were never used as true C&C – instead they were used as proxies to redirect traffic to the real C&C, whose location remains unknown. Here’s what the full picture looks like:

Answering the questions

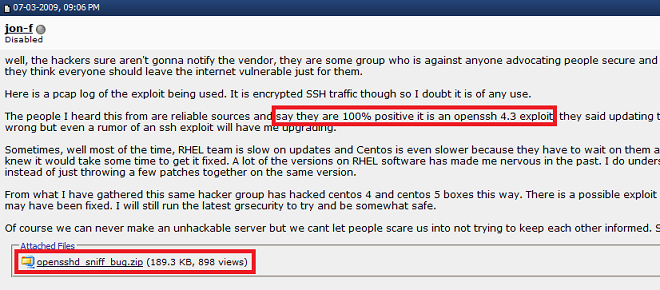

So, how did these servers get hacked in the first place? One crazy theory points to a 0-day vulnerability in OpenSSH 4.3. Searching for “openssh 4.3 0-day” on Google finds some very interesting posts. One of them is (https://www.webhostingtalk.com/showthread.php?t=873301):

This post from user “jon-f”, which dates back to 2009, indicates a possible 0-day in OpenSSH 4.3 on CentOS; he even posted sniffed logs of the exploit in action, although they are encrypted and not easy to analyze.

Could this be the case here? Knowing the Duqu guys and their never-ending bag of 0-day exploits, does it mean they also have a Linux 0-day against OpenSSH 4.3? Unfortunately, we do not know.

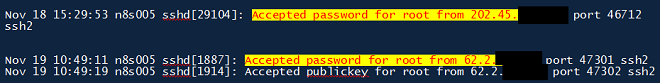

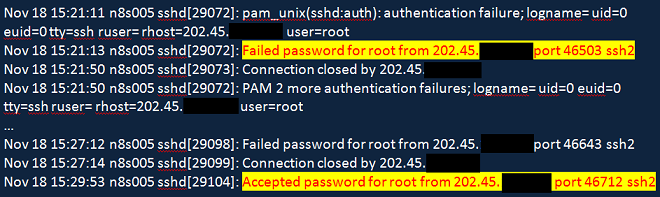

If we look at the “sshd.log” from 18 November 2009, we can, however, get some interesting clues. The “root” user attempts to log in using a password multiple times from an IP in Singapore, until they finally succeed:

Note how the “root” user tries to login at 15:21:11, fails a couple of times and then 8 minutes and 42 seconds later the login succeeds. This is more of an indication of a password bruteforcing rather a 0-day. So the most likely answer is that the root password was bruteforced.

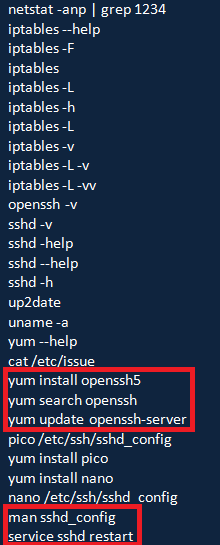

Nevertheless, the third question remains: Why did the attackers replace the stock OpenSSH 4.3 with version 5.8? On the server in Germany we were able to recover parts of the “.bash_history” file just after the server was hacked:

The relevant commands are “yum install openssh5”, then “yum update openssh-server”. There must be a good reason why the attackers are so concerned about updating OpenSSH 4.3 to version 5. Unfortunately, we do not know the answer to this question. On an interesting note, we observed that the attackers are not exactly familiar with the “iptables” command line syntax. Additionally, they are not very sure about the “sshd_config” file format either, so they needed to bring up the manual for it (“man sshd_config”) as well as for the standard Linux ftp client. What about the “sshd_config” file, the sshd configuration”? Once again, by searching the slack space we were able to identify what they were after. In particular, they changed the following two lines:

GSSAPIAuthentication yes

UseDNS no

While the second one is relevant for speed, especially when performing port direction over tunnels, the first one enables Kerberos authentication. We were able to determine that in other cases exactly the same modifications were applied.

Conclusion:

We have currently analyzed only a fraction of the available Duqu C&C servers. However, we were able to determine certain facts about how the infrastructure operated:

- The Duqu C&C servers operated as early as November 2009.

- Many different servers were hacked all around the world, in Vietnam, India, Germany, Singapore, Switzerland, the UK, the Netherlands, Belgium, South Korea to name but a few locations. Most of the hacked machines were running CentOS Linux. Both 32-bit and 64-bit machines were hacked.

- The servers appear to have been hacked by bruteforcing the root password. (We do not believe in the OpenSSH 4.3 0-day theory – that would be too scary!)

- The attackers have a burning desire to update OpenSSH 4.3 to version 5 as soon as they get control of a hacked server.

- A global cleanup operation took place on 20 October 2011. The attackers wiped every single server which was used even in the distant past, e.g. 2009. Unfortunately, the most interesting server, the C&C proxy in India, was cleaned only hours before the hosting company agreed to make an image. If the image had been made earlier, it’s possible that now we’d know a lot more about the inner workings of the network.

- The “real” Duqu mothership C&C server remains a mystery just like the attackers’ identities.

We would also like to send a question to Linux admins and OpenSSH experts worldwide – why would you update OpenSSH 4.3 to version 5.8 as soon as you hack a machine running version 4.3? What makes version 5.8 so special compared to 4.3? Is it related to the option “GSSAPIAuthentication yes” in the config file?

We hope that through cooperation and working together we can cast more light on this huge mystery of the Duqu Trojan.

Kaspersky Lab would like to thank the companies PA Vietnam, Nara Syst and the Bulgarian CyberCrime unit for their kind support in this investigation. This wouldn’t have been possible without their cooperation.

You can contact the Kaspersky Duqu research team at “stopduqu AT Kaspersky DOT com”.

The Mystery of Duqu: Part Six (The Command and Control servers)