In our previous blogpost, we discussed the Madi campaign, uncovered through joint research with our partner Seculert (http://blog.seculert.com/2012/07/mahdi-cyberwar-savior.html).

In this blogpost, we will continue our analysis with information on the Madi infrastructure, communications, data collection, and victims.

The Madi infrastructure performs its surveillance operations and communications with a simple implementation as well. Five command and control (C2) web servers are currently up and running Microsoft IIS v7.0 web server along with exposed Microsoft Terminal service for RDP access, all maintaining identical copies of the custom, C# server manager software. These servers also act as the stolen data drops. The stolen data seems to be poorly organized on the server side, requiring multiple operators to log in and investigate the data per each of the compromised systems that they are managing over time.

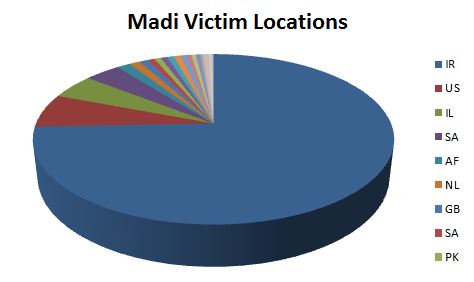

The services at these IP addresses have been cycled through by the operators for unknown reasons. There does not appear to be a pattern to which malware reports to which server just yet. According to sinkhole data and other reliable sources, the approximate locations of Madi victims are distributed mainly within the Middle East, but some are scattered lightly throughout the US and EU. It seems that some of the victims are professionals and academia (both students and staff) running laptops infected with the Madi spyware, travelling throughout the world:

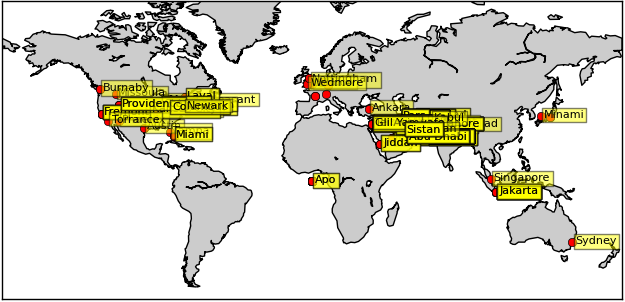

Here is an approximate global map representing the approximate location of Madi victims, dependent on GeoIP data. While the overwhelming percentage of Madi victims in the middle east is not best visualized in this graphic, it helps to understand the Madi reach:

Some related domains not under our sinkhole were quickly sinkholed by other security groups the day after our post. But the problem with the timing and approach by these newcomers is that the spyware and downloaders currently active do not “speak” with those domains, for the most part. Instead, they speak directly with the web servers running according to their hard-coded IP addresses, avoiding any DNS name resolution. To help with this process, the malware authors built update functionality into the downloaders. If they were switching their pool of infected systems to another domain or IP address, a Madi downloader or infostealer would communicate with its assigned C2 server and then retrieve the IP or domain of its new C2, store the new locator in a plain text file on the drive, and then switch over and begin communicating with the new C2. This approach also seems crude in comparison to other resilient cybercrime infrastructure.

When source IP addresses are examined from systems checking in to the C2 by hand and matched up with their ASN, the most activity is clearly coming from within Iran:

Iran 84%

Pakistan 6%

US 3%

IL 1%

UAE <1%

Saudi Arabia <1%

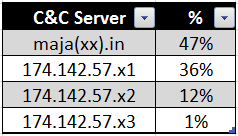

We distributed the largest collection of related samples so far to multiple vendors and incident response handlers. Only a couple of vendors have responded in kind with only a few binaries that are new to our collection. Accordingly, these numbers are the most accurate that research has to offer at this point, even as new Madi samples are uploaded to our backend services:

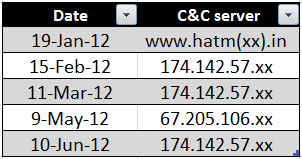

C2 locators hard-coded into Madi downloaders

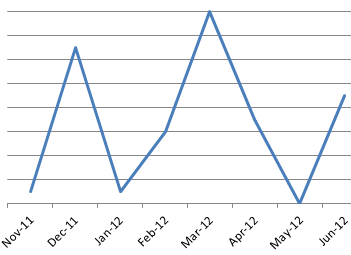

A timeline of new activity can be scoped out for the group, with the greatest number of related downloaders created by the developers in December 2011, Feb and March of 2012, followed by June of 2012. Also, the oldest Madi trojan currently in the collection was created in Sept. 2011, most likely during the testing phase of the project. The domain that it reports to was created on August 10, 2011.

This information tends to make sense, as other researchers discussed privately that spear-phishing campaign volumes appeared to be heaviest in February 2012, but this information was collected from the targets outside of Iran. We don-t know about any sort of activity intensity timeline within Iran, although the trends above may help inform those questions.

We also know that the infostealers are a much smaller pool of code, and were released on a separate timeline. We have discovered five months in which the Madi infostealers were created, and the matching URL that they communicated with for instructions and to upload victim screenshots, keylogged data, stolen documents and contracts:

In addition to the information we presented here, our partner Seculert posted their own analysis of the Madi C2 infrastructure here: http://blog.seculert.com/2012/07/mahdi-numbers-and-flame-connection.html.

Note: On July 25, we received a new variant of Madi which connects to a new C2 server in Canada. We are still investigating it and the data from this post does not include this new C2 server.

The Madi Campaign – Part II