For several months, we have been monitoring an ongoing cyber-espionage campaign against South Korean think-tanks. There are multiple reasons why this campaign is extraordinary in its execution and logistics. It all started one day when we encountered a somewhat unsophisticated spy program that communicated with its “master” via a public e-mail server. This approach is rather inherent to many amateur virus-writers and these malware attacks are mostly ignored.

However, there were a few things that attracted our attention:

- The public e-mail server in question was Bulgarian – mail.bg.

- The compilation path string contained Korean hieroglyphs.

These two facts compelled us take a closer look at this malware — Korean compilers alongside Bulgarian e-mail command-and-control communications.

The complete path found in the malware presents some Korean strings:

D:rsh공격UAC_dll(완성)Releasetest.pdb

The “rsh” word, by all appearances, means a shortening of “Remote Shell” and the Korean words can be translated in English as “attack” and “completion”, i.e.:

D:rshATTACKUAC_dll(COMPLETION)Releasetest.pdb

Although the full list of victims remains unknown, we managed to identify several targets of this campaign. According to our technical analysis, the attackers were interested in targeting following organizations”.

The Sejong Institute

The Sejong Institute is a non-profit private organization for public interest and a leading think tank in South Korea, conducting research on national security strategy, unification strategy, regional issues, and international political economy.

Korea Institute For Defense Analyses (KIDA)

KIDA is a comprehensive defense research institution that covers a wide range of defense-related issues. KIDA is organized into seven research centers: the Center for Security and Strategy; the Center for Military Planning; the Center for Human Resource Development; the Center for Resource Management; the Center for Weapon Systems Studies; the Center for Information System Studies; and the Center for Modeling and Simulation. KIDA also has an IT Consulting Group and various supporting departments. KIDA’s mission is to contribute to rational defense policy-making through intensive and systematic research and analysis of defense issues.

Ministry of Unification

The Ministry of Unification is an executive department of the South Korean government responsible for working towards the reunification of Korea. Its major duties are: establishing North Korea Policy, coordinating inter-Korean dialogue, pursuing inter-Korean cooperation and educating the public on unification.

Hyundai Merchant Marine

Hyundai Merchant Marine is a South Korean logistics company providing worldwide container shipping services.

Some clues also suggest that computers belonging to “The supporters of Korean Unification” (http://www.unihope.kr/) were also targeted. Among the organizations we counted, 11 are based in South Korea and two entities reside in China.

Partly because this campaign is very limited and highly targeted, we have not yet been able to identify how this malware is being distributed. The malicious samples we found are the early stage malware most often delivered by spear-phishing e-mails.

Infecting a system

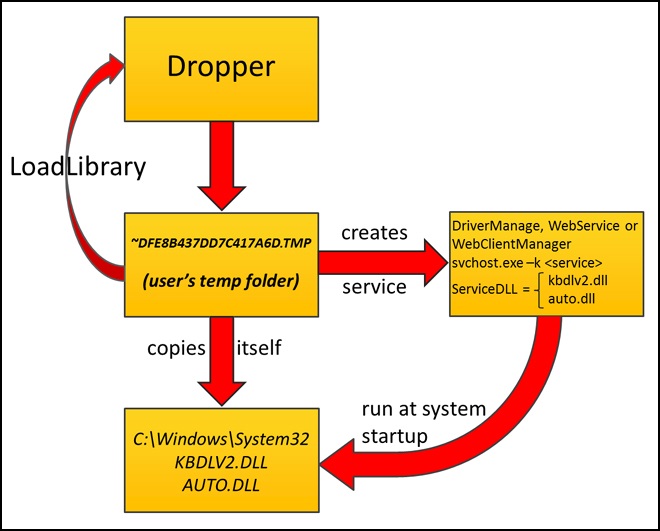

The initial Trojan dropper is a Dynamic Link Library functioning as a loader for further malware. It does not maintain exports and simply delivers another encrypted library maintained in its resource section. This second library performs all the espionage functionality.

When running on Windows 7, the malicious library uses the Metasploit Framework’s open-source code Win7Elevate to inject malicious code into explorer.exe. In any case, be it Windows 7 or not, this malicious code decrypts its spying library from resources, saves it to disk with an apparently random but hardcoded name, for example, ~DFE8B437DD7C417A6D.TMP, in the user’s temporary folder and loads this file as library.

This next stage library copies itself into the System32 directory of the Windows folder after the hardcoded file name — either KBDLV2.DLL or AUTO.DLL, depending on the malware sample. Then the service is created for the service dll. Service names also can differ from version to version; we discovered the following names — DriverManage, WebService and WebClientManager. These functions assure malware persistence in a compromised OS between system reboots.

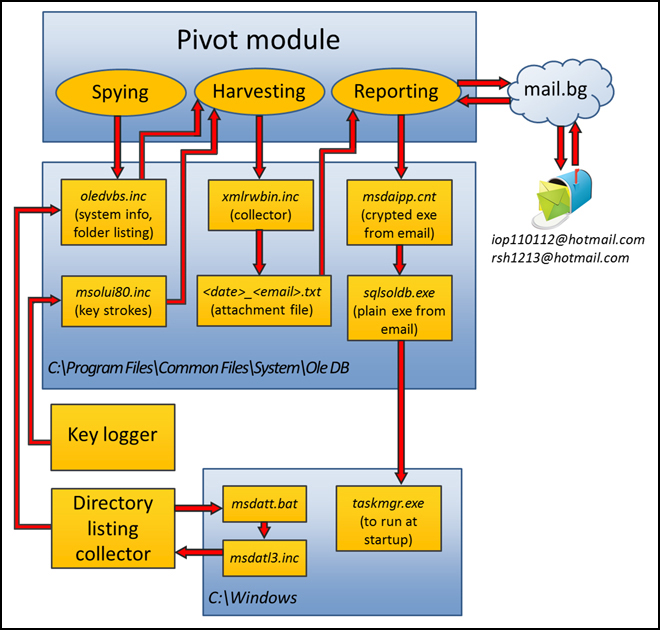

At this stage, the malware gathers information about the infected computer. This includes an output of the systeminfo command saved in the file oledvbs.inc by following the hardcoded path: C:Program FilesCommon FilesSystemOle DBoledvbs.inc. There is another function called – the malware creates a string containing computer and user names but this isn’t used anywhere. By all appearances, this is a mistake by the malware author. Later on, we will come to a function where such a string could be pertinent but the malware is not able to find this data in the place where it should be. These steps are taken only if it’s running on an infected system for the first time. At system startup, the malicious library performs spying activities when it confirms that it is loaded by the generic svchost.exe process.

Spying modules

There are a lot of malicious programs involved in this campaign but, strangely, they each implement a single spying function. Besides the basic library (KBDLV2.DLL / AUTO.DLL) that is responsible for common communication with its campaign master, we were able to find modules performing the following functions:

- Keystroke logging

- Directory listing collection

- HWP document theft

- Remote control download and execution

- Remote control access

Disabling firewall

At system startup, the basic library disables the system firewall and any AhnLab firewall (a South Korean security product vendor) by zeroing out related values in registry:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

SYSTEMCurrentControlSetServicesSharedAccessParameters FirewallPolicyStandardProfile EnableFirewall = 0 SYSTEMCurrentControlSetServicesSharedAccessParameters FirewallPolicyPublicProfile EnableFirewall = 0 HKLMSOFTWAREAhnLabV3IS2007InternetSec FWRunMode = 0 HKLMSOFTWAREAhnlabV3IS80is fwmode = 0 |

It also turns off the Windows Security Center service to prevent alerting the user about the disabled firewall.

It is not accidental that the malware author has singled out AhnLab’s security product. During our Winnti research, we learnt that one of the Korean victims was severely criticized by South Korean regulators for using foreign security products. We do not know for sure how this criticism affected other South Korean organizations, but we do know that many South Korean organizations install AhnLab security products. Accordingly, these attackers don’t even bother evading foreign vendors’ products, because their targets are solely South Korean.

Once the malware disables the AhnLab firewall, it checks whether the file taskmgr.exe is located in the hardcoded C:WINDOWS folder. If the file is present, it runs this executable. Next, the malware loops every 30 minutes to report itself and wait for response from its operator.

Communications

Communication between bot and operator flows through the Bulgarian web-based free email server (mail.bg). The bot maintains hardcoded credentials for its e-mail account. After authenticating, the malware sends e-mails to another specified e-mail address, and reads e-mails from the inbox. All these activities are performed via the “mail.bg” web-interface with the use of the system Wininet API functions. From all the samples that we managed to obtain, we extracted the following email accounts used in this campaign:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

beautifl@mail.bg ennemyman@mail.bg fasionman@mail.bg happylove@mail.bg lovest000@mail.bg monneyman@mail.bg sportsman@mail.bg veryhappy@mail.bg |

Here are the two “master” email addresses to which the bots send e-mails on behalf of the above-mentioned accounts. They report on status and transmit infected system information via attachments:

|

1 2 |

iop110112@hotmail.com rsh1213@hotmail.com |

Regular reporting

To report infection status, the malware reads from C:Program FilesCommon FilesSystemOle DBoledvbs.inc which contains the systeminfo command output. If the file exists, it is deleted after reading.

Then, it reads user-related info from the file sqlxmlx.inc in the same folder (we can see strings referencing to “UserID” commentary in this part of the code). But this file was never created. As you recall, there is a function that should have collected this data and should have saved it into this sqlxmlx.inc file. However, on the first launch, the collected user information is saved into “xmlrwbin.inc”. This effectively means that the malware writer mistakenly coded the bot to save user information into the wrong file. There is a chance for the mistaken code to still work — user information could be copied into the send information heap. But not in this case – at the time of writing, the gathered user information variable which should point to the xmlrwbin.inc filename has not yet been initialized, causing the file write to fail. We see that sqlxmlx.inc is not created to store user information.

Next, the intercepted keystrokes are read from the file and sent to the master. Keystrokes are logged and kept in an ordinary and consistent format in this file – both the names of windows in which keys were typed and the actual sequence of keyboard entry. This data is found in the file C:Program FilesCommon FilesSystemOle DBmsolui80.inc created by the external key logger module.

All this data is merged in one file xmlrwbin.inc, which is then encrypted with RC4. The RC4 key is generated as an MD5 hash of a randomly generated 117-bytes buffer. To be able to decipher the data, the attacker should certainly know either the MD5 hash or the whole buffer content. This data is also sent, but RSA encrypted. The malware constructs a 1120 bit public key, uses it to encrypt the 117-bytes buffer. The malware then concatenates all the data to be sent as a 128-bytes block. The resulting data is saved in C:Program FilesCommon FilesSystemOle DB to a file named according to the following format:

“<system time>_<account at Bulgarian email server>.txt”, for example, “08191757_beautifl@mail.bg.txt”.

The file is then attached to an e-mail and sent to the master’s e-mail account. Following transmission, it is immediately deleted from the victim system.

Getting the master’s data

The malware also retrieves instructions from the mail server. It checks for mails in its Bulgarian e-mail account with a particular subject tag. We have identified several “subject tags” in the network communication: Down_0, Down_1, Happy_0, Happy_2 and ddd_3. When found and the e-mail maintains an attachment, the malware downloads this attachment and saves it with filename “msdaipp.cnt” in C:Program FilesCommon FilesSystemOle DB. The attacker can send additional executables in this way. The executables are RC4 encrypted and then attached. The key for decryption is hardcoded in the malicious samples. It’s interesting that the same “rsh!@!#” string is maintained across all known samples and is used to generate RC4 keys. As described earlier, the malware computes the MD5 of this string and uses the hash as its RC4 key to decrypt the executable. Then, the plain executable is dropped onto disk as “sqlsoldb.exe” and run, and then moved to the C:Windows folder with the file name “taskmgr.exe”. The original e-mail and its attachment are then deleted from the Bulgarian e-mail inbox.

Key logger

The additional key logger module is not very complex — it simply intercepts keystrokes and writes typed keys into C:Program FilesCommon FilesSystemOle DBmsolui80.inc, and also records the active window name where the user pressed keys. We saw this same format in the Madi malware. There is also one key logger variant that logs keystrokes into C:WINDOWSsetup.log.

Directory listing collector

The next program sent to victims enumerates all the drives on the infected system and executes the following command on them:

dir <drive letter>: /a /s /t /-c

In practice, this command is written to C:WINDOWSmsdatt.bat and executed with output redirected to C:WINDOWSmsdatl3.inc. As a result, the latter maintains a listing of all files in all the folders on the drive. The malware later reads that data and appends it to content of the file C:Program FilesCommon FilesSystemOle DBoledvbs.inc. At this point, “oledvbs.inc “already stores systeminfo output.

It’s interesting that one sample of the directory listing collector was infected with the infamous “Viking” virus of Chinese origin. Some of this virus’ modifications were wandering in the wild for years and its authors or operators would never expect to see it end up in a clandestine APT-related spying tool. For the attackers, this is certainly a big failure. Not only does the original spying program have marks of well-known malware that can be detected by anti-malware products; moreover the attackers are revealing their secret activities to cyber-criminal gangs. However, by all appearances, the attackers noticed the unwanted addition to their malware and got rid of the infection. This was the only sample bearing the Viking virus.

Due to expensive work of malware with variety of additional files, it’s not out of place to show these “relationships” in a diagram:

HWP document stealer

This module intercepts HWP documents on an infected computer. The HWP file format is similar to Microsoft Word documents, but supported by Hangul, a South Korean word processing application from the Hancom Office bundle. Hancom Office is widely used in South Korea. This malware module works independently of the others and maintains its own Bulgarian e-mail account. The account is hardcoded in the module along with the master’s e-mail to which it sends intercepted documents. It is interesting that the module does not search for all the HWP files on infected computer, but reacts only to those that are opened by the user and steals them. This behavior is very unusual for a document-stealing component and we do not see it in other malicious toolkits.

The program copies itself as <Hangul full path>HncReporter.exe and changes the default program association in the registry to open HWP documents. To do so, it alters following registry values:

|

1 2 3 |

HKEY_CLASSES_ROOTHwp.Document.7shellopencommand or HKEY_CLASSES_ROOTHwp.Document.8shellopencommand |

By default, there is the registry setting “<Hangul full path>Hwp.exe” “%1” associating Hangul application “Hwp.exe” with .HWP documents. But the malicious program replaces this string with the following: “<Hangul full path>HncReporter.exe ” “%1”. So, when the user is opening any .HWP document, the malware program itself is executed to open the .HWP document. Following this registry edit, any opened .HWP document is read and sent as an e-mail attachment with the subject “Hwp” to the attackers. After sending, the malware executes the real Hangul word processing application “Hwp.exe” to open the .HWP document as the user intended. The means the victim most likely will not notice the theft of the .HWP file. The module’s sending routine depends on the following files in C:Program FilesCommon FilesSystemOle DB folder: xmlrwbin.inc, msdaipp.cnt, msdapml.cnt, msdaerr.cnt, msdmeng.cnt and oledjvs.inc.

Remote control module downloader

An extra program is dedicated exclusively to download attachments out of incoming e-mails with a particular subject tag. This program is similar to the pivot module but with reduced functionality: it maintains the hardcoded Bulgarian e-mail account, logs in, reads incoming e-mails and searches for the special subject tag “Team“. When found, it loads the related attachment, drops it onto the hard drive as C:Program FilesCommon FilesSystemOle DBtaskmgr.exe and executes. This particular executable arrives without any encryption.

Remote control module

It is also interesting that the malware author did not custom develop a backdoor program. Instead, the author modified TeamViewer client version 5.0.9104. The initial executable pushed by attackers in e-mails related to the remote control module consists of three more executables. Two of them are Team Viewer components themselves, and another is some sort of backdoor loader. So, the dropper creates three files in the C:WindowsSystem32 directory:

|

1 2 3 |

netsvcs.exe - the modified Team Viewer client; netsvcs_ko.dll - resources library of Team Viewer client; vcmon.exe - installer/starter; |

and creates the service “Remote Access Service“, adjusted to execute C:WindowsSystem32vcmon.exe at system startup. Every time the vcmon.exe is executed, it disables AhnLab’s firewall by zeroing out following registry values:

|

1 2 3 |

HKLMSOFTWAREAhnLabV3 365 ClinicInternetSec UseFw = 0 UseIps = 0 |

Then, it modifies the Team Viewer registry settings. As we said, the Team Viewer components used in this campaign are not the original ones. They are slightly modified. In total, we found two different variants of changed versions. The malware author replaced all the entries of “Teamviewer” strings in Team Viewer components. In the first case with the “Goldstager” string and with the string “Coinstager” in the second. TeamViewer client registry settings are then HKLMSoftwareGoldstagerVersion5 and HKLMSoftwareCoinstagerVersion5 correspondingly. The launcher sets up several registry values that control how the remote access tool will work. Among them is SecurityPasswordAES. This parameter represents a hash of the password with which a remote user has to connect to Team Viewer client. This way, the attackers set a pre-shared authentication value. After that, the starter executes the very Team Viewer client netsvcs.exe.

Who’s Kim?

It’s interesting that the drop box mail accounts iop110112@hotmail.com and rsh1213@hotmail.com are registered with the following “kim” names: kimsukyang and “Kim asdfa”.

Of course, we can’t be certain that these are the real names of the attackers. However, the selection isn’t frequently seen. Perhaps it also points to the suspected North Korean origin of attack. Taking into account the profiles of the targeted organizations — South Korean universities that conduct researches on international affairs, produce defense policies for government, national shipping company, supporting groups for Korean unification — one might easily suspect that the attackers might be from North Korea.

The targets almost perfectly fall into their sphere of interest. On the other hand, it is not that hard to enter arbitrary registration information and misdirect investigators to an obvious North Korean origin. It does not cost anything to concoct fake registration data and enter kimsukyang during a Hotmail registration. We concede that this registration data does not provide concrete, indisputable information about the attackers.

However, the attackers’ IP-addresses do provide some additional clues. During our analysis, we observed ten IP-addresses used by the Kimsuky operators. All of them lie in ranges of the Jilin Province Network and Liaoning Province Network, in China.

No other IP-addresses have been uncovered that would point to the attackers’ activity and belong to other IP-ranges. Interestingly, the ISPs providing internet access in these provinces are also believed to maintain lines into North Korea. Finally, this geo-location supports the likely theory that the attackers behind Kimsuky are based in North Korea.

Appendix

Files used by malware:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 |

%windir%system32kbdlv2.dll %windir%system32auto.dll %windir%system32netsvcs.exe %windir%system32netsvcs_ko.dll %windir%system32vcmon.exe %windir%system32svcsmon.exe %windir%system32svcsmon_ko.dll %windir%system32wsmss.exe %temp%~DFE8B437DD7C417A6D.TMP %temp%~DFE8B43.TMP %temp%~tmp.dll C:Windowstaskmgr.exe C:Windowssetup.log C:Windowswinlog.txt C:Windowsupdate.log C:Windowswmdns.log C:Windowsoledvbs.inc C:Windowsweoig.log C:Windowsdata.dat C:Windowssys.log C:WindowsPcMon.exe C:WindowsGoogle Update.exe C:WindowsReadMe.log C:Windowsmsdatt.bat C:Windowsmsdatl3.inc C:Program FilesCommon FilesSystemOle DBmsdmeng.cnt C:Program FilesCommon FilesSystemOle DBxmlrwbin.inc C:Program FilesCommon FilesSystemOle DBmsdapml.cnt C:Program FilesCommon FilesSystemOle DBsqlsoldb.exe C:Program FilesCommon FilesSystemOle DBoledjvs.inc C:Program FilesCommon FilesSystemOle DBoledvbs.inc C:Program FilesCommon FilesSystemOle DBmsolui80.inc C:Program FilesCommon FilesSystemOle DBmsdaipp.cnt C:Program FilesCommon FilesSystemOle DBmsdaerr.cnt C:Program FilesCommon FilesSystemOle DBsqlxmlx.inc <Hangul full path>HncReporter.exe |

Related MD5:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 |

3baaf1a873304d2d607dbedf47d3e2b4 3195202066f026de3abfe2f966c9b304 4839370628678f0afe3e6875af010839 173c1528dc6364c44e887a6c9bd3e07c 191d2da5da0e37a3bb3cbca830a405ff 5eef25dc875cfcb441b993f7de8c9805 b20c5db37bda0db8eb1af8fc6e51e703 face9e96058d8fe9750d26dd1dd35876 9f7faf77b1a2918ddf6b1ef344ae199d d0af6b8bdc4766d1393722d2e67a657b 45448a53ec3db51818f57396be41f34f 80cba157c1cd8ea205007ce7b64e0c2a f68fa3d8886ef77e623e5d94e7db7e6c 4a1ac739cd2ca21ad656eaade01a3182 4ea3958f941de606a1ffc527eec6963f 637e0c6d18b4238ca3f85bcaec191291 b3caca978b75badffd965a88e08246b0 dbedadc1663abff34ea4bdc3a4e03f70 3ae894917b1d8e4833688571a0573de4 8a85bd84c4d779bf62ff257d1d5ab88b d94f7a8e6b5d7fc239690a7e65ec1778 f1389f2151dc35f05901aba4e5e473c7 96280f3f9fd8bdbe60a23fa621b85ab6 f25c6f40340fcde742018012ea9451e0 122c523a383034a5baef2362cad53d57 2173bbaea113e0c01722ff8bc2950b28 2a0b18fa0887bb014a344dc336ccdc8c ffad0446f46d985660ce1337c9d5eaa2 81b484d3c5c347dc94e611bae3a636a3 ab73b1395938c48d62b7eeb5c9f3409d 69930320259ea525844d910a58285e15 |

Names of services created by malware:

|

1 2 3 4 |

DriverManage WebService WebClientManager Remote Access Service |

We detect these threats as Trojan.Win32.Kimsuky except modified Team Viewer client components which are detected as Trojan.Win32.Patched.ps.

The “Kimsuky” Operation: A North Korean APT?