The Process Doppelgänging technique was first presented in December 2017 at the BlackHat conference. Since the presentation several threat actors have started using this sophisticated technique in an attempt to bypass modern security solutions.

In April 2018, we spotted the first ransomware employing this bypass technique – SynAck ransomware. It should be noted that SynAck is not new – it has been known since at least September 2017 – but a recently discovered sample caught our attention after it was found to be using Process Doppelgänging. Here we present the results of our investigation of this new SynAck variant.

Anti-analysis and anti-detection techniques

Process Doppelgänging

SynAck ransomware uses this technique in an attempt to bypass modern security solutions. The main purpose of the technique is to use NTFS transactions to launch a malicious process from the transacted file so that the malicious process looks like a legitimate one.

Binary obfuscation

To complicate the malware analysts’ task, malware developers often use custom PE packers to protect the original code of the Trojan executable. Most packers of this type, however, are effortlessly unpacked to reveal the original unchanged Trojan PE file that’s suitable for analysis.

This, however, is not the case with SynAck. The Trojan executable is not packed; instead, it is thoroughly obfuscated prior to compilation. As a result, the task of reverse engineering is considerably more complicated with SynAck than it is with other recent ransomware strains.

The control flow of the Trojan executable is convoluted. Most of the CALLs are indirect, and the destination address is calculated by arithmetic operation from two DWORD constants.

All of the WinAPI function addresses are imported dynamically by parsing the exports of system DLLs and calculating a CRC32-based hash of the function name. This in itself is neither new nor particularly difficult to analyze. However, the developers of SynAck further complicated this approach by obscuring both the address of the procedure that retrieves the API function address, and the target hash value.

Let’s illustrate in detail how SynAck calls WinAPI functions. Consider the following piece of disassembly:

This code takes the DWORD located at 403b13, subtracts the constant 78f5ec4d, with the result 403ad0, and calls the procedure at this address.

This procedure pushes two constants (N1 = ffffffff877bbca1 and N2 = 2f399204) onto the stack and passes the execution to the procedure at 403680 which will calculate the result of N1 xor N2 = a8422ea5.

This value is the hash of the API function name that SynAck wants to call. The procedure 403680 will then find the address of this function by parsing the export tables of system DLLs, calculating the hash of each function name and comparing it to the value a8422ea5. When this API function address is found, SynAck will pass the execution to this address.

Notice that instead of a simple CALL in the image above it uses the instructions PUSH + RET which is another attempt to complicate analysis. The developers of SynAck use different instruction combinations instead of CALL when calling WinAPI functions:

push reg

retn- jmp reg

mov [rsp-var], reg

jmp qword ptr [rsp-var]

Deobfuscation

To counter these attempts by the malware developers, we created an IDAPython script that automatically parses the code, extracts the addresses of all intermediate procedures, extracts the constants and calculates the hashes of the WinAPI functions that the malware wants to import.

We then calculated the hash values of the functions exported from Windows system DLLs and matched them against the values required by SynAck. The result was a list showing which hash value corresponds to which API function.

Our script then uses this list to save comments in the IDA database to indicate which API is going to be called by the Trojan. Here is the code from the example above after deobfuscation.

Language check

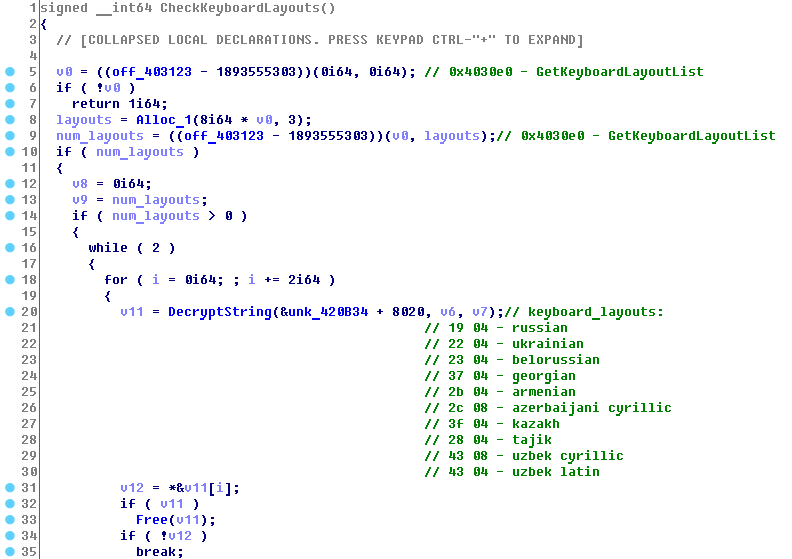

At an early stage of execution the Trojan performs a check to find out whether it has been launched on a PC from a certain list of countries. To do this, it lists all the keyboard layouts installed on the victim’s PC and checks against a list hardcoded into the malware body. If it finds a match, SynAck sleeps for 300 seconds and then just calls ExitProcess to prevent encryption of files belonging to a victim from these countries.

Directory name validation

Shortly after the language check, which can be considered fairly common among modern ransomware, SynAck performs a check on the directory where its executable is started from. If there’s an attempt to launch it from an ‘incorrect’ directory, the Trojan won’t proceed and will just exit instead. This measure has been added by the malware developers to counter automatic sandbox analysis.

As with API imports, the Trojan doesn’t store the strings it wants to check; instead it stores their hashes – a tactic that hinders efforts to find the original strings.

SynAck contains nine hashes; we have been able to brute-force two of them:

0x05f9053d == hash("output")

0x2cd2f8e2 == hash("plugins")In the process we found a lot of collisions (gibberish strings that give the same hash value as the meaningful ones).

Cryptographic scheme

Like other ransomware, SynAck uses a combination of symmetric and asymmetric encryption algorithms. At the core of the SynAck algorithm lies the hybrid ECIES scheme. It is composed of ‘building blocks’ which interact with each other: ENC (symmetric encryption algorithm), KDF (key derivation function), and MAC (message authentication code). The ECIES scheme can be implemented using different building blocks. To calculate a key for the symmetric algorithm ENC, this scheme employs the ECDH protocol (Diffie-Hellman over a chosen elliptic curve).

The developers of this Trojan chose the following implementation:

ENC: XOR

KDF: PBKDF2-SHA1 with one iteration

MAC: HMAC-SHA1

ECDH curve: standard NIST elliptic curve secp192r1

ECIES-XOR-HMAC-SHA1

This is the function that implements the ECIES scheme in the SynAck sample.

Input: plaintext, input_public_key

Output: ciphertext, ecies_public_key, MAC

- The Trojan generates a pair of asymmetric keys: ecies_private_key and ecies_public_key;

- Using the generated ecies_private_key and input_public_key the Trojan calculates the shared secret according to the Diffie-Hellman protocol on an elliptic curve:

ecies_shared_secret = ECDH(ecies_private_key, input_public_key) - Using the PBKDF2-SHA1 function with one iteration, the Trojan derives two byte arrays, key_enc and key_mac, from ecies_shared_secret. The size of key_enc is equal to the size of the plaintext;

- The plaintext is XORed byte to byte with the key_enc;

- The Trojan calculates the MAC (message authentication code) of the obtained ciphertext using the algorithm HMAC-SHA1 with key_mac as the key.

Initialization

At the first step the Trojan generates a pair of private and public keys: the private key (session_private_key) is a 192-bit random number and the public key (session_public_key) is a point on the standard NIST elliptic curve secp192r1.

Then the Trojan gathers some unique information such as computer and user names, OS version info, unique infection ID, session private key and some random data and encrypts it using a randomly generated 256-bit AES key. The encrypted data is saved as the encrypted_unique_data buffer.

To encrypt the AES key, the Trojan uses the ECIES-XOR-HMAC-SHA1 function (see description above; hereafter referred to as the ECIES function). SynAck passes the AES key as the plaintext parameter and the hardcoded cybercriminal’s master_public_key as input_public_key. The field encrypted_aes_key contains the ciphertext returned by the function, public_key_n is the ECIES public key and message_authentication_code is the MAC.

At the next step the Trojan forms the structure cipher_info.

struct cipher_info

{

uint8_t encrypted_unique_data[240];

uint8_t public_key_n[49];

uint8_t encrypted_aes_key[44];

uint8_t message_authentication_code[20];

};It is shown in the image below.

This data is then encoded in base64 and written into the ransom note.

As we can see, the criminals ask the victim to include this encoded text in their message.

File encryption

The content of each file is encrypted by the AES-256-ECB algorithm with a randomly generated key. After encryption, the Trojan forms a structure containing information such as the encryption label 0xA4EF5C91, the used AES key, encrypted chunk size and the original file name. This information can be represented as a structure:

struct encryption_info

{

uint32_t label = 0xA4EF5C91;

uint8_t aes_key[32];

uint32_t encrypted_chunk_size;

uint32_t reserved;

uint8_t original_name_buffer[522];

};The Trojan then calls the ECIES function and passes the encryption_info structure as the plaintext and the previously generated session_public_key as the input_public_key. The result returned by this function is saved into a structure which we dubbed file_service_structure. The field encrypted_file_info contains the ciphertext returned by the function, ecc_file_key_public is the ECIES public key and message_authentication_code is the MAC.

struct file_service_structure

{

uint8_t ecc_file_key_public[49];

encryption_info encrypted_file_info;

uint8_t message_authentication_code[20];

};This structure is written to the end of the encrypted file. This results in an encrypted file having the following structure:

struct encrypted_file

{

uint8_t encrypted_data[file_size - file_size % AES_BLOCK_SIZE];

uint8_t original_trailer[file_size % AES_BLOCK_SIZE];

uint64_t encryption_label = 0x65CE3D204A93A12F;

uint32_t infection_id;

uint32_t service_structure_size;

file_service_structure service_info;

};The encrypted file structure is shown in the image below.

After encryption the files will have randomly generated extensions.

Other features

Termination of processes and services

Prior to file encryption, SynAck enumerates all running processes and all services and checks the hashes of their names against two lists of hardcoded hash values (several hundred combined). If it finds a match, the Trojan will attempt to kill the process (using the TerminateProcess API function) or to stop the service (using ControlService with the parameter SERVICE_CONTROL_STOP).

To find out which processes it wants to terminate and which services to stop, we brute-forced the hashes from the Trojan body. Below are some of the results.

| Processes | Services | ||

| Hash | Name | Hash | Name |

| 0x9a130164 | dns.exe | 0x11216a38 | vss |

| 0xf79b0775 | lua.exe | 0xe3f1f130 | mysql |

| 0x6475ad3c | mmc.exe | 0xc82cea8d | qbvss |

| 0xe107acf0 | php.exe | 0xebcd4079 | sesvc |

| 0xf7f811c4 | vds.exe | 0xf3d0e358 | vmvss |

| 0xcf96a066 | lync.exe | 0x31c3fbb6 | wmsvc |

| 0x167f833f | nssm.exe | 0x716f1a42 | w3svc |

| 0x255c7041 | ssms.exe | 0xa6332453 | memtas |

| 0xbdcc75a9 | w3wp.exe | 0x82953a7a | mepocs |

| 0x410de6a4 | excel.exe | ||

| 0x9197b633 | httpd.exe | ||

| 0x83ddb55a | ilsvc.exe | ||

| 0xb27761ed | javaw.exe | ||

| 0xfd8b9308 | melsc.exe | ||

| 0xa105f60b | memis.exe | ||

| 0x10e94bcc | memta.exe | ||

| 0xb8de9e34 | mepoc.exe | ||

| 0xeaa98593 | monad.exe | ||

| 0x67181e9b | mqsvc.exe | ||

| 0xd6863409 | msoia.exe | ||

| 0x5fcab0fe | named.exe | ||

| 0x7d171368 | qbw32.exe | ||

| 0x7216db84 | skype.exe | ||

| 0xd2f6ce06 | steam.exe | ||

| 0x68906b65 | store.exe | ||

| 0x6d6daa28 | vksts.exe | ||

| 0x33cc148e | vssvc.exe | ||

| 0x26731ae9 | conime.exe | ||

| 0x76384ffe | fdhost.exe | ||

| 0x8cc08bd7 | mepopc.exe | ||

| 0x2e883bd5 | metray.exe | ||

| 0xd1b5c8df | mysqld.exe | ||

| 0xd2831c37 | python.exe | ||

| 0xf7dc2e4e | srvany.exe | ||

| 0x8a37ebfa | tabtip.exe | ||

As we can see, SynAck seeks to stop programs related to virtual machines, office applications, script interpreters, database applications, backup systems, gaming applications and so on. It might be doing this to grant itself access to valuable files that could have been otherwise used by the running processes.

Clearing the event logs

To impede possible forensic analysis of an infected machine, SynAck clears the event logs stored by the system. To do so, it uses two approaches. For Windows versions prior to Vista, it enumerates the registry key SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\EventLog and uses OpenEventLog/ClearEventLog API functions. For more modern Windows versions, it uses the functions from EvtOpenChannelEnum/EvtNextChannelPath/EvtClearLog and from Wevtapi.dll.

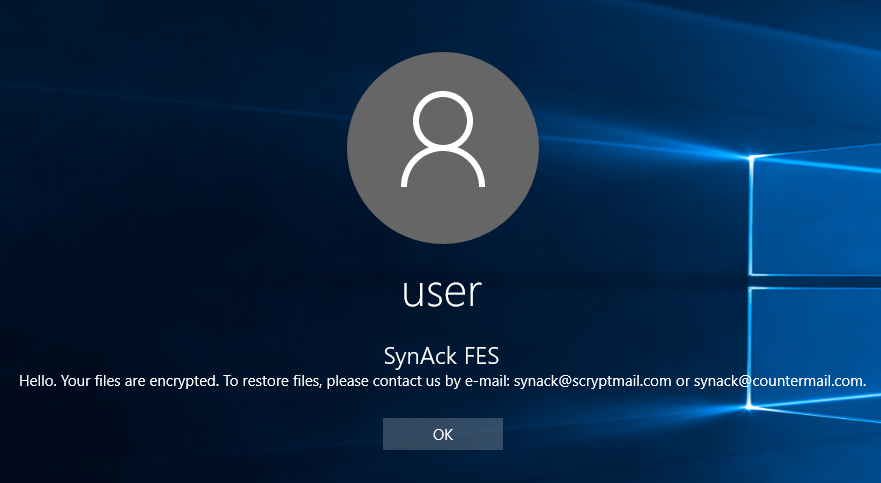

Ransom note on logon screen

SynAck is also capable of adding a custom text to the Windows logon screen. It does this by modifying the LegalNoticeCaption and LegalNoticeText keys in the registry. As a result, before the user signs in to their account, Windows shows a message from the cybercriminals.

Attack statistics

We have currently only observed several attacks in the USA, Kuwait, Germany, and Iran. This leads us to believe that this is targeted ransomware.

Detection verdicts

Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Agent.abwa

Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Agent.abwb

PDM:Trojan.Win32.Generic

IoCs

0x6F772EB660BC05FC26DF86C98CA49ABC

0x911D5905CBE1DD462F171B7167CD15B9

SynAck targeted ransomware uses the Doppelgänging technique

Jimmy JOhnson

Sample is not availale any where. Can you please share samples or sha2?

zh4ck

Hey guys, in “directory validation” try “syswow64”, “system32” and “kernel33” .. anyway is there any possibility that this trojan was developed as testing tool by synack.com pentesters? And it could leak during some pentest?

Ariel2211

You have any tool to remove it and to decrypt the files? or any samples?