Spring Dragon is a long running APT actor that operates on a massive scale. The group has been running campaigns, mostly in countries and territories around the South China Sea, since as early as 2012. The main targets of Spring Dragon attacks are high profile governmental organizations and political parties, education institutions such as universities, as well as companies from the telecommunications sector.

In the beginning of 2017, Kaspersky Lab became aware of new activities by an APT actor we have been tracking for several years called Spring Dragon (also known as LotusBlossom).

Information about the new attacks arrived from a research partner in Taiwan and we decided to review the actor’s tools, techniques and activities.

Using Kaspersky Lab telemetry data we detected the malware in attacks against some high-profile organizations around the South China Sea.

Spring Dragon is known for spear phishing and watering hole techniques and some of its tools have previously been analyzed and reported on by security researchers, including Kaspersky Lab. We collected a large set (600+) of malware samples used in different attacks, with customized C2 addresses and campaign codes hardcoded in the malware samples.

Spring Dragon’s Toolset

The threat actor behind Spring Dragon APT has been developing and updating its range of tools throughout the years it has been operational. Its toolset consists of various backdoor modules with unique characteristics and functionalities.

The threat actor owns a large C2 infrastructure which comprises more than 200 unique IP addresses and C2 domains.

The large number of samples which we have managed to collect have customized configuration data, different sets of C2 addresses with new hardcoded campaign IDs, as well as customized configuration data for creating a service for malware on a victim’s system. This is designed to make detection more difficult.

All the backdoor modules in the APT’s toolset are capable of downloading more files onto the victim’s machine, uploading files to the attacker’s servers, and also executing any executable file or any command on the victim’s machine. These functionalities enable the attackers to undertake different malicious activities on the victim’s machine.

A detailed analysis of known malicious tools used by this threat actor is available for customers of Kaspersky Threat Intelligence Services.

Command and Control (C2) Infrastructure

The main modules in Spring Dragon attacks are backdoor files containing IP addresses and domain names of C2 servers. We collected and analyzed information from hundreds of C2 IP addresses and domain names used in different samples of Spring Dragon tools that have been compiled over the years.

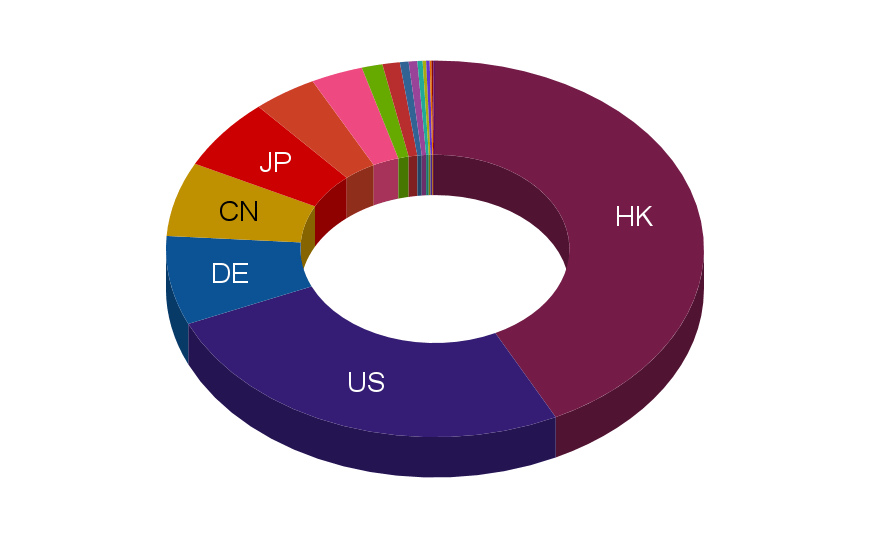

In order to hide their real location, attackers have registered domain names and used IP addresses from different geographical locations. The chart below shows the distribution of servers based on geographical location which the attackers used as their C2 servers.

Distribution chart of C2 servers by country

Distribution chart of C2 servers by country

More than 40% of all the C2 servers used for Spring Dragon’s operations are located in Hong Kong, which hints at the geographical region (Asia) of the attackers and/or their targets. The next most popular countries are the US, Germany, China and Japan.

Targets of the Attacks

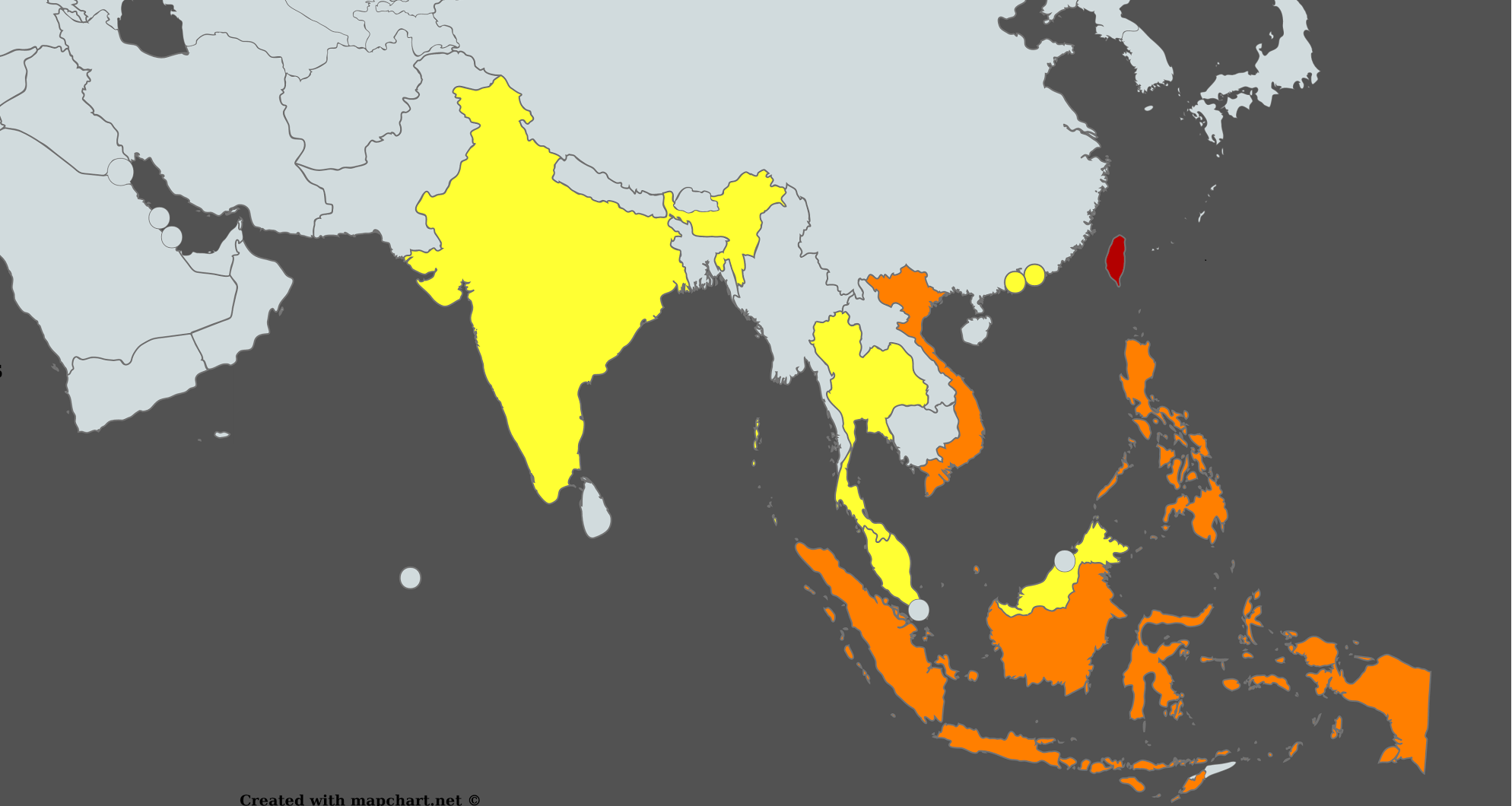

As was mentioned, the Spring Dragon threat actor has been mainly targeting countries and territories around the South China Sea with a particular focus on Taiwan, Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines, Hong Kong, Malaysia and Thailand.

Our research shows that the main targets of the attacks are in the following sectors and industries:

- High-profile governmental organizations

- Political parties

- Education institutions, including universities

- Companies from the telecommunications sector

The following map shows the geographic distribution of attacks according to our telemetry, with the frequency of the attacks increasing from yellow to red.

Origin of the Attacks

The victims of this threat actor have always been mainly governmental organizations and political parties. These are known to be of most interest to state-supported groups.

The type of malicious tools the actor has implemented over time are mostly backdoor files capable of stealing files from victims’ systems, downloading and executing additional malware components as well as running system commands on victims’ machines. This suggests an intention to search and manually collect information (cyberespionage). This activity is most commonly associated with the interests of state-sponsored attackers.

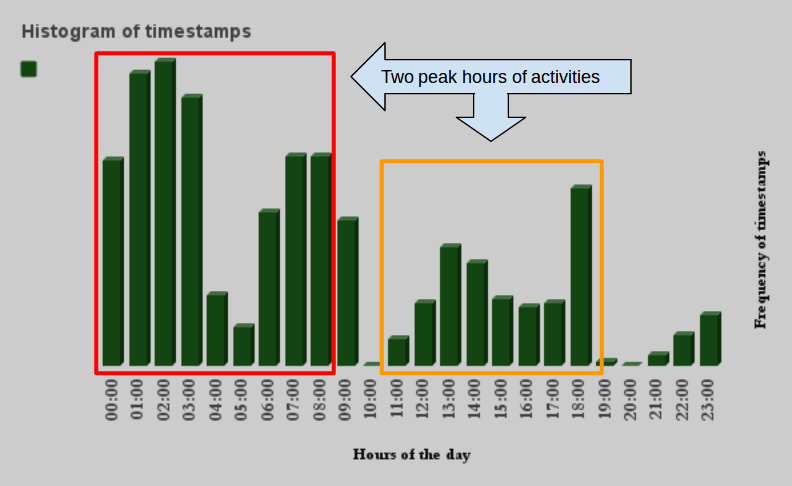

As a routine analysis procedure, we decided to figure out the attacker’s possible time zone using the malware compilation timestamps from a large number of Spring Dragon samples. The following diagram shows the frequency of the timestamps during daytime hours. The timestamps range from early 2012 until now and are aligned to the GMT time zone.

Assuming the peak working hours of malware developers are the standard working day of 09:00-17:00, the chart shows that compilation took place in the GMT+8 time zone. It also suggests that either there is a second group working another shift in the same time zone or the attackers are cross-continental and there is another group, possibly in Europe. The uneven distribution of timestamps (low activity around 10am, 7-8pm UTC) suggests that the attackers didn’t change the timestamps to random or constant values and they might be real.

Histogram of malware files’ timestamps

Histogram of malware files’ timestamps

Conclusions

Spring Dragon is one of many long-running APT campaigns by unknown Chinese-speaking actors. The number of malware samples which we managed to collect (over 600) for the group surpassed many others, and suggests an operation on a massive scale. It’s possible that this malware toolkit is offered in specialist public or private forums to any buyers, although, to date, we haven’t seen this.

We believe that Spring Dragon is going to continue resurfacing regularly in the Asian region and it is therefore worthwhile having good detection mechanisms (such as Yara rules and network IDS signatures) in place. We will continue to track this group going forward and, should the actor resurface, we will provide updates on its new modus operandi.

More information is available to Kaspersky Lab private report subscribers. Please contact intelreports@kaspersky.com.

References

Below is the list of public references and reports related to the Spring Dragon attackers:

- Securelist – https://securelist.com/blog/research/70726/the-spring-dragon-apt/

- Palo Alto Networks – http://researchcenter.paloaltonetworks.com/2015/06/operation-lotus-blossom/

- Palo Alto Networks IoC2 – https://github.com/pan-unit42/iocs/tree/master/lotusblossom

- Palo Alto Networks 2 – http://researchcenter.paloaltonetworks.com/2015/12/attack-on-french-diplomat-linked-to-operation-lotus-blossom/

- Palo Alto Networks Unit 42, full report – https://app.box.com/s/xhn6ru62qqom1kuxoe3mxnqrtb1sqw2q

- TrendMicro – http://www.trendmicro.com.my/vinfo/my/security/news/cyber-attacks/esile-targeted-attack-campaign-hits-apac-governments

- TrendMicro – http://s.itho.me/infosec/2016/AT8.pdf

- PwC – http://pwc.blogs.com/cyber_security_updates/2015/12/elise-security-through-obesity.html

Spring Dragon – Updated Activity