Experts at Kaspersky have been investigating various computer incidents on a daily basis for over a decade. Having been in the field for so long, we have witnessed some major changes in the cybercrime world’s modus operandi. This report shares our insights into the Russian-speaking cybercrime world and the changes in how it operates that have happened in the past five years.

We overview what kind of attacks are now carried out by cybercriminals and what influenced this change — including such factors as changes in vulnerability market and browser safety. We also review what pushed cybercriminals to transform their operations into the now well-known malware-as-a-service model — the use of cloud servers, the decreasing relevance of custom malware and the subsequent emergence of small, agile teams. Lastly, we analyze the targets that cybercriminals select these days as opposed to a few years back, the reasoning behind them and criminal-to-criminal services offered on the dark web.

While this report is primarily focused on cybercriminals that operate on Russian territory, cybercriminals rarely restrict themselves to national borders — with ransomware gangs being a prime example of such cross-border activity. Moreover, trends that are visible in one country, more often than not resurface in other places and among new cybercriminal gangs. This report attempts to shed light on the changes in cybercriminals’ operations that we deem important — and actionable.

Incident analysis

Kaspersky’s Computer Incident Investigations Department specializes in attacks by Russian-speaking and Russia-based cybercriminals. The services we offer include incident analysis, investigation and post-incident expert support, all directed at preventing and mitigating the consequences of cyberattacks.

Back in 2016, the primary focus of our expert was on major cybergangs that targeted financial institutions, banks in particular. Big names such as Lurk, Buhtrap, Metel, RTM, Fibbit and Carbanak boldly terrorized banks nationwide, yet eventually fell apart or ended up behind bars — with our help too. Others cybercriminal groups, such as Cerberus, left the game and shared their source code with the world.

These days, the industries under attack are not limited to financial institutions, while major attacks like those we investigated back in the day thankfully are no longer possible. On top of that, due to changes in legislation that limited financial institutions in hiring external services, the number of cases we investigated for financial industry clients in 2020 was zero.

We investigated 200 cases for clients in Russia in 2020, and already over 300 in the first nine months of 2021. The industries affected included everything from IT to retail, from oil and gas to healthcare. This is a surprising trend, as one would expect COVID-19 and the move to remote working to have prompted more computer incidents. But our visibility showed otherwise.

Key trends

The cybercriminal ecosystem has always consisted of various roles. The main constants in this system are the infrastructure needed for carrying out cybercriminal activity and the instruments used for this activity. The roles of people in the game directly depend on the infrastructure and the instruments — and these have changed. Let’s delve into some of the major shifts that have taken place in the cybersecurity sphere in the past five years and see how they have transformed the way Russian-speaking cybercriminals operate.

Client-side attacks on the wane

It may be hard to imagine these days, but just five years ago to get your computer infected with a Trojan was as easy as visiting a news website. In fact, a lot of malware in Russia was distributed “straight from the front page” — via news platforms and other legitimate websites. True, web attacks are not a thing of the past yet, but with increasing browser security, attacks via this vector have become much harder. Previously, many cybercriminals lived simply by distributing exploits via legitimate websites. A whole market was built around that process — with dedicated staff to make it roll.

At the time, browsers were full of vulnerabilities, offered bad user experience and were generally insecure. Many used browsers that they were accustomed to, not browsers of choice, or default browsers set by organizations, such as the Internet Explorer. Attacks via plugins, such as Adobe Flash, Silverlight and Java, were also among the easiest and most often used ways to infect user devices — and now they are a thing of the past.

In 2021, browsers are much safer, with some of them updating automatically, without any user participation, while browser developers continually invest in vulnerabilities assessment. Furthermore, with the development of numerous bug-bounty programs, it has become easier to sell discovered vulnerabilities to developers themselves, rather than look for a buyer on the dark web. That also led to higher prices for vulnerabilities.

With safer browsers, web infections have become more challenging and, ultimately, unattractive to cybercriminals. As a result, targeting regular rather than corporate users with such means has become too expensive and not commercially viable.

Vulnerabilities market got a remake

Applications have become more complex, their architecture better. This has radically changed the way Russian-speaking cybercriminals operate.

With vulnerabilities rising in price, client-side operations have become extremely difficult and expensive. Client-side infections used to rely heavily on vulnerabilities; entire teams would look for them and write exploits for particular vulnerabilities — adjusted for different operating systems. Most often, cybercriminals exploited 1-day vulnerabilities — they examined developers’ patches recently rolled out and wrote exploits for vulnerabilities that were closed. However, since the software update period was (and still is) quite long, users often updated their devices with a delay, therefore leaving a window during which cybercriminals could infect quite a few victims.

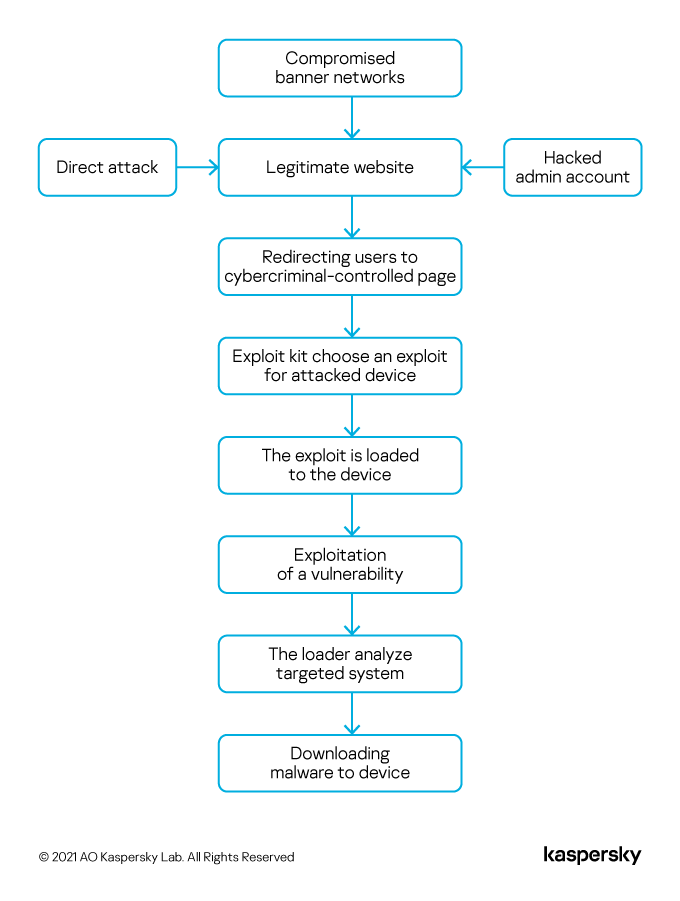

A typical infection chain looked like this: a legitimate website was compromised — just five years ago securing websites wasn’t really the done thing. It could be compromised directly or by hacking the account of someone with access to the website management. The attacker would integrate some piece of code — it could be a window on the page, invisible to the user. Then, since the target would continue to use the website, it would also load the page controlled by the attackers. Another option was to compromise a banner network — with banners being available across myriad sites and the website management not having a vote on what ad was displayed. It was also possible to simply buy and direct traffic to a specific malicious page. Ultimately, the goal was to covertly lead the user to a page controlled by the attackers, with this page containing code that would exploit one of the vulnerabilities in the user’s browser.

This browser attack chain, popular in 2016, is no longer possible

To ensure more users were infected, cybercriminal groups developed exploit kits for specific user groups and tailored exploits downloaded to victims’ devices. After running the exploit, the attackers would choose a specific payload to be downloaded to the infected device. The payload usually resulted in remote access to the computer. Once infected, the device would be assessed based on how attractive it was to the cybercriminals. After that, the attackers would load a specific exploit that would assess the interest of the infected device, and then a specific malware was uploaded to it (if the victim was interesting at all).

With such browser attacks being no longer viable, nor easy to execute, a whole array of different players were no longer in demand. This included groups that specialized in purchasing and directing traffic to specific pages with exploits, groups that developed and sold exploit packs, groups that purchased access to specific devices (the latter still exist, albeit they sell it to different players now).

Of course, vulnerabilities in client-side software remained — just now they are not in browsers, but in various types of documents such as PDF or Word with Macros options typically distributed via email. Still, this change makes attacks and the infection process much harder. Unlike with browser infections, when distributing a malicious file hidden in a PDF or Word, the attacker is not able to receive feedback from the victim or additional information about the device the target uses. Browsers, on the other hand, reported what versions of software and plugins they have automatically. This way, with attackers switching to distributing malicious files via phishing emails, it has become more difficult to track the version of the user’s software, or how far the attack went. On top of that, safety mechanisms in email servers and in applications such as Word also made it harder to carry out an infection — many emails containing malicious files are not intercepted before they get to the target, while users receive regular warnings inside applications about potentially dangerous attachments.

Cloud servers for all

Infrastructure is needed for communication and data storage.

As organizations progress in the adoption of new IT-services, so do cybercriminals who follow the same trends and changes. Moving to cloud services instead of regular servers has freed their hands. Before, cybercriminals would rent the servers — quite legitimately, albeit often not under their own names. In 2016, complaints against servers that were connected to suspicious activities were easier to ignore — at the time, some organizations offered bullet-proof servers that would ignore user complaints. However, as time went by, managing such servers has become harder and less profitable — a result of greater interest in cybercrime on the part of local authorities.

Cybercriminals also used to hack into servers of organizations to use them as relay servers to throw investigators off the scent and make it harder to trace the main C&C center. Sometimes cybergangs would store some information — for instance, data extracted from victims— on servers they had compromised. This sort of structure with data being spread over various platforms required dedicated staff to manage it.

The adoption of cloud servers made life easier for cybercriminals — now, if multiple complaints resulted in the suspension of an account, moving the data to a new server was a two-minute job. It also meant that the teams no longer needed a dedicated admin to manage the server — this task was outsourced to the cloud server provider.

Malware developers — no longer hiring

Perhaps the scariest trend of all is how easy it has become for cybercriminals to gain access to new effective malware. While APT actors continue to invest large funds and resources into tailor-made malicious tools, cybercriminals choose the easier, less costly way, which no longer includes developing their own malware or exploits.

Open-source malware is appearing on the dark web more and more often — it has become a trend for established cybergangs to release their source code to the public for free, making it fairly easy for new players to start their cybercriminal activity. The developers of Cerberus, a banking Trojan, released the source code of their malware in October 2020, while Babuk, the developer of the infamous ransomware of the same name, had their ransomware code released early in September 2021.

To make matters worse, with the development of penetration-testing tools and services, the dark market saw the rise of new malicious tools. These tools are developed and used for legitimate services, such as assessing clients’ security infrastructure and potential for successful network penetration. They are meant to be sold to a carefully selected client base that would only use them for legitimate purposes. Yet, inevitably, these tools eventually end up in the hands of cybercriminals. One of the most notable examples is cybercriminals’ favorite CobaltStrike, a decompiled version of which was leaked in November 2020 — and is now seen in active use by both cybercriminals and APT groups. Others include Bloodhound, another favorite cybercriminal tool for network mapping, Kali and Commando VM for specialized distribution, Core Impact and Metaspoit Framework for exploiting vulnerabilities, use of netscan.exe (softPerfect Network Scanner) on compromised computers, and legitimate services for remote access, such as TeamViewer, AnyDesk and RMS/LMS. To top it off, cybercriminals make use of legitimate services that are meant to help system administrators, such as PSexec, which allows remote execution of programs. Understandably, such tools have risen in popularity since the pandemic and the consequent rise in remote working.

These days, to understand what kind of tools cybercriminals use, it is enough to see what pen-testers deploy and offer on the market.

Essentially, the malware development market has reached its maturity stage. Given the abundance of information, starting a cybercriminal operation is easier than ever before. At the same time, it has become more difficult to attack companies. Protection systems do not stand still; awareness is growing. The pen-testing market, too, exists due to the demand for it, with large organizations investing in making their networks safer.

The results

Optimizing the chain — smaller teams

These structural shifts (rising vulnerabilities costs, moving to cloud servers, accessibility of already developed advanced offensive tools) has led to cybergangs shrinking. Essentially, the attack chain has been optimized with many roles having been outsourced, and teams becoming more agile.

System administrators that take care of physical networks are no longer needed — with cloud services management being an easy task. Cybercriminal gangs have also essentially put a stop to developing their own malicious software. If before, large cybercriminal groups would invest in their own malware and therefore staff at the very least two developers to work on different parts of the malware (for instance client and server side), now they only need an operator. If developers are not needed, neither are testers. The long attack chain that included exploits for different vulnerabilities has also shrunk — and so exploit writers that focused on client side have been put out of business.

Buying traffic for malicious sites has transformed into buying data — access to different organizations, account information, etc. These services, too, have been outsourced.

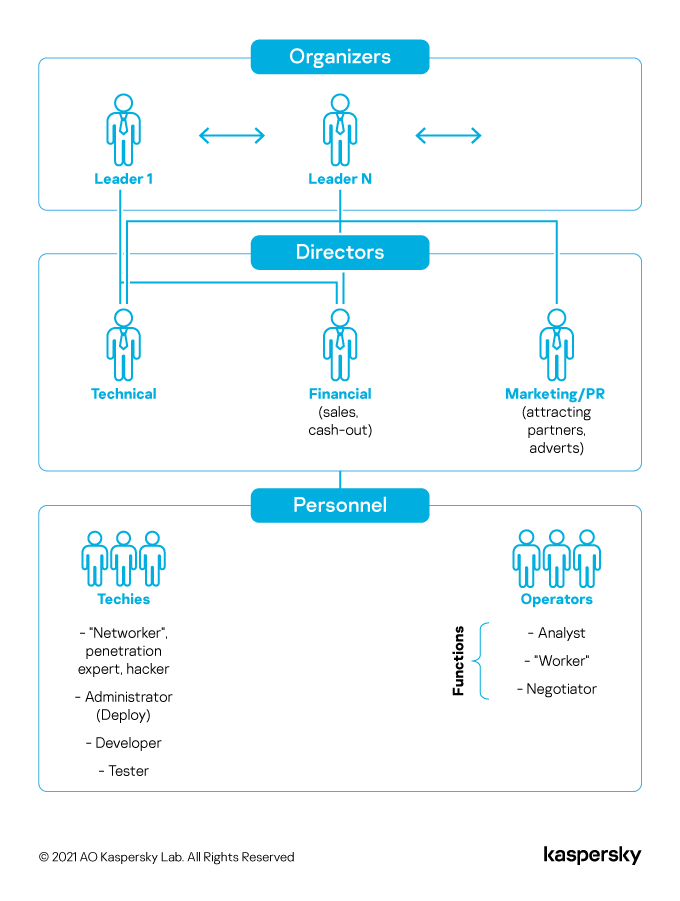

As a result, for a successfully running operation in 2021, a cybergang needs management, malware operators, specialists in gaining network access and financial specialists that take care of extracting and cashing out the stolen funds.

|

|

Then and now: a comparison of how cybercrime groups looked in 2016 vs 2021

We are yet to see what will happen to those cybercriminals who were jailed in 2016-2017 and will be released into a world where their skillsets are no longer in demand. It is hard to tell whether they will settle for an honest path, but if not, there are no vacancies for them in the current dark cybermarket.

Change of targets

The year 2016 saw banks in Russia hacked one after another. It was also a time when regular users had their devices infected and goods stolen. As time went by, and big gangs that targeted financial institutions were ambushed, Russian-speaking cybercriminals switched to other industries, attacking both large and small businesses. By 2018, however, they had realized that it is far more profitable to target organizations — with ransomware, stealers or remote access tools for conducting financial operations from within the networks.

In 2020, we witnessed a drop in cases against financial institutions in Russia. Incidents that included banking software pretty much left the stage. There were a few reasons for this: new local financial security regulations and enhanced banking security. But, most importantly, cybercriminals switched to targets in the West. We cannot confirm that the operators of attacks against financial institutions are the same people that now operate in ransomware gangs, yet it is safe to assume that cybercriminals who had been put out of a job switched to new, juicier targets. We did a separate review of the Russian-language ransomware ecosystem earlier this year, so we will not go in length about them here.

Western organizations are chosen by cybercriminals not for ideological reasons. First, organizations located in Europe and the US have more funds, and the potential for profit is higher than in the case of infecting a Russian company. For instance, for international companies, ransom demands start from 700 thousand USD and can go up to 7 million USD. When attacking Russian organizations, the ransomware gangs start their demands from 100 thousand. On average, ransomware operators end up getting a ransom ranging from 50 to 100 thousand USD. Widespread use of English also makes companies more susceptible to attacks.

At the same time, the shift to the West does not mean that Russian companies are no longer being attacked from within the country. Criminals are still mostly limited by linguistic constraints — it is much easier to prepare phishing emails and documents in their native language. This is the only advantage of Russian-speaking hackers when attacking Russian companies. Such choice of targets, however, entails higher risks for the cybercriminals — the likelihood of them being discovered and arrested is greater.

Industry-wise, cybercriminals are no longer limited to financial institutions. The advent of botnets created a market of network access — companies from all types of industries are broken into without particular targeting, and access to them is later sold off on the dark web. The pandemic also played a role in boosting it, with companies moving much of their infrastructure online and opening it up to remote workers, leading to a wider attack surface and more ways to hack into otherwise better-protected networks. Quite often, ransomware operators go for the low-hanging fruit — companies that are easiest to break into and get some profit off. Another big focus is organizations and users that possess or operate cryptocurrency — cryptoexchanges, cryptowallets and others are among the juicy targets.

Some trends and attacks are purely local and tied to the Russian language. For instance, somewhat surprisingly, since 2019 vishing (voice phishing, i.e. phone scams) has enjoyed a renaissance. Russia’s mature mobile banking industry coupled with IP-telephone technologies made it very easy and profitable to set up hard-to-trace call centers that scam regular users out of their money. As a result, the damage for regular Russian users amounts to about 1 billion rubles (13.8 million USD) monthly.

Services in demand

The world of dark-web marketplaces has also transformed. While, indeed, there still are a few popular platforms where cybercriminals can meet and offer their services, serious players are moving more and more to the shadows. A prime example of that is ransomware operators, who have been expelled from popular dark-web platforms due to the heightened interest in their activities. Now, they tend to communicate privately. The availability of secure messengers also played a role, as cybercriminals connect directly, not via forums.

We no longer see vulnerabilities or exploits for sale on the dark web, as truly valuable vulnerabilities, such as 0-day ones, are rare and sold directly to select customers, while 1-day vulnerabilities are sold to agencies that specialize in them.

Still, many services remain in demand on the dark web and offers for them can still be found without much effort. Let’s go over the key services cybercriminals use:

- Ready-made accounts — using online services such as clouds requires cybercriminals to have emails and phone numbers, and for obvious reasons making their own is not safe enough. Prepaid SIM cards are illegal in Russia — all users must register SIM cards to their ID. Therefore, emails bundled with phone numbers are always in demand.

- Access to logins — besides the regular phone+email combination, cybercriminals offer stolen credentials for all types of accounts — from gaming and streaming accounts to banking and other services. These credentials can be used for a whole variety of activities — from scams to extraction of funds.

- Access to organizations — perhaps the most attractive type of offer. Many operators specialize solely in infecting networks en masse via botnets or through exploiting 1-day vulnerabilities. Having gained access to a company network, they assess the attractiveness of the company and sell access to other cybercriminals, who then work on harvesting or encrypting the company’s data.

- DDoS attacks — still in demand, albeit protection against DDoS attacks has become stronger.

- Personal data — the amount of personal data available on the dark web continues to grow and diversify. The types of data have moved from card or ID data to rarer types, such as medical information or full access to banking accounts. The price of this data starts as low as 0.5 USD per item. We covered the type of data available on the dark web in our previous report.

Conclusion: cybersecurity and cybercrime have matured

A few years back, the digital market was being tested by cybercriminals; radically new ways of attacking users and organizations were being developed on a regular basis. Now, in 2021, we have reached the point when the cybercriminal world has matured. So has cybersecurity — just a few years ago organizations had little understanding of what dangers they face online. Now, after waves of notorious and devastating attacks, people have become more cautious, and organizations recognize the potential cyberrisks and invest in mitigating them. Here are the main takeaways from this overview of the state of Russian-speaking cybercrime:

- Information has become more accessible and that includes malware. Malicious tools are available online in abundance — be it leaked or released source code of infamous malware developed by now-gone cybergangs, or legal instruments used for pen-testing by organizations. This accessibility benefits cybercriminals, as they no longer need to invest time and resources in writing malware from scratch.

- Cybergangs as we knew them are gone. People in cybercrime are less and less tied to each other, and no longer exist in stable groups that last many years.

- Cybergangs operate like small businesses that deliver various services. People in cybercrime have become very effective at outsourcing — focusing on purchasing access to hacked organizations and the right tools to exploit that access. They no longer need to write malware, nor take care of physical servers.

- Russian-speaking cybercrime has also moved across the borders. As the digital world lacks traditional borders, the limitations of potential targets are dictated by the language cybercriminals speak; thus, the English-speaking part of the world will always remain appealing. It would be presumptuous to say that back in 2016 Russian-speaking cybercriminals did not attack users abroad, or that they completely ceased to attack their fellow nationals. Nevertheless, the clampdown by law enforcement of those who attack organizations within Russia and much higher potential profit from attacks on international organizations has solidified the “do not work in RU” rule and brought Russian-speaking cybercriminals under the spotlight of the international arena.

- Everyone is a target now. With so many organizations facing the Internet, the attack surface has grown immensely, and gaining access to organizations has become easier. Cybercriminals are ready to lay their hands on pretty much any organization, as opposed to their past focus on financial organizations. With ransomware, every victim can bring profit to a cybergang.

- Data remains a valuable asset. The current state of personal data security paints a gloomy picture. Regardless of the current, though significant, efforts made by various governments, personal data continues to end up online, and used for attacks — be it a tool to register a server for a cybergang or a point of access to an organization. This is unlikely to change in the near future.

All in all, the current state of Russian-speaking cybercrime reveals problems in cybersecurity of global relevance. In the “shared” cybercriminal economy, tracking specific gangs has become harder, while the gangs themselves have ceased to be well-defined entities, turning into rather scattered groups of individuals with the right tools, which are easy to access. What we as cybersecurity experts can do is strive to be a step ahead — and continue to build defenses, educate people and make cybersecurity front-of-mind for everyone.

Russian-speaking cybercrime evolution: What changed from 2016 to 2021

Clausewitz 4.0

QUOTE: “Of course, vulnerabilities in client-side software remained — just now they are not in browsers”

Totally wrong. Vulnerabilities are still in the browser, mobile or desktop, they are a lot, just there is a sandbox to escape now, the stack got fancy, on top of that there are DEP, ASLR, etc..

QUOTE: “Unlike with browser infections, when distributing a malicious file hidden in a PDF or Word, the attacker is not able to receive feedback”

Totally wrong. A macro can report all that back to c2.

J

Yeah macros are popular malware vectors but thanks to technologies like AMSI and HIPS, delivering malware payload via macros became much harder. AMSI allows the antivirus program to read a macro script, and HIPS prevent commonly used applications such as Word from performing tasks that are classified as malicious such as a macro spawning child processes or making system calls.

Leo

Very good

Adres

I adore examining and I believe this website got some really useful stuff on it! .

AI

Could you please to help me for Crypto scam recovery , how I can deal with Cryptocurrency scam in Russia ?