Dreams of a Threat Actor

There are two crucial features of the Android OS protection system:

- it is impossible to download a file without user’s knowledge on a clean device;

- it is impossible to initialize installation of a third-party app without user’s knowledge on a clean device.

These approaches greatly complicate malware writers’ lives: to infect a mobile device, they have to resort to ruses of social engineering. The victim is literally tricked into force-installing a Trojan. This is definitely not always possible, as users become more aware, and it is not that easy to trick them.

Invisible installation of a malware app onto a mobile device without a user’s knowledge is definitely a daydream of many a malware writer. To do that, it is necessary to find and exploit an Android system vulnerability. These vulnerabilities have been found: we are talking about CVE-2012-6636, CVE-2013-4710, and CVE-2014-1939.

These vulnerabilities allow to execute any code on a device by means of a custom-made HTML page with a JavaScript code. The vulnerabilities have been closed, starting with Android 4.1.2.

It would be great to say that everything is fine now, but, alas, that is not so. We should not forget about the third feature of the Android OS: a device manufacturer is responsible for creating and deploying updates for its specific device model.

Updating the Android operating system is decentralized: each company uses its own custom version of Android, compiled with its own compilers and supplied with its own optimization and drivers. Regardless of who has found a vulnerability and whether that person has informed the OS developer about it, releasing updates is a prerogative of each manufacturer. Only manufacturers are capable of helping the users.

Nevertheless, updates are released somewhat periodically but mostly for the leading models: not all of the manufacturers actively support all of their models.

A publically available detailed description of vulnerabilities for the Android OS provides malware writers with all of the required knowledge. Incidentally, a potential victim of the vulnerability exploits can remain such for a long period of time: let us call it “an endless 0-day”. The problem can be solved only by buying a new device.

This, in particular, coupled with publically available descriptions of the vulnerabilities and examples of the vulnerabilities being exploited, incited malware writers into developing an exploit and performing drive-by attacks onto mobile devices.

Web Site Infection

Drive-by attacks on computers of unsuspecting users give a large audience to threat actors (if they manage to post a malicious code on popular web sites) as well as invisibility (inasmuch as users do not suspect being infected). Owners of compromised web sites may not suspect being infected for a long time as well.

The method of code placement and other attack features allow one to distinguish web sites infected with the same “infection”. For quite long, we observed a typical infection within a group of minimum several dozens of Russian web sites of different types and attendances, including quite well-known and popular resources (for example, web sites with a daily turn-out of 25,000 and 115,000 users). Web-site infection from this group is characterized by the usage of the same intermediate domains, the similarity of the malicious code placed onto them, the method of code placement (in most cases, it is placed on the same domain as an individual JavaScript file), as well as speed and synchronicity of changes in the code on all of the infected web sites after the malicious code has been detected.

The attack method has been standard (even though it has gone through some changes), and it has been used at least since 2014. It has been standard also owing to its targeting Windows OS users. However, some time ago, after threat actors performed a regular modification of the code on infected web sites, we discovered a new script instead of a “common” one that uploads flash exploits. It checked for the “Android 4” setting in User-Agent and operated with tools uncommon for Windows. This anomaly urged us to study the functionality of the script meticulously and watch the infection more closely.

Thus, on the 22nd of January 2016, we discovered a JavaScript code that exploited an Android vulnerability. Only within 3 days, on the 25th of January 2016, we found a new modification of this script with more threatening features.

Scripts

We managed to detect two main script modifications.

Script 1: Sending SMS

The only goal of the first script is to send an SMS message to a phone number of threat actors with the word “test”. For that, the malware writers took advantage of the Android Debug Bridge (ADB) client that exists on all of the devices. The script executes a command to check for the ADB version on a device using the Android Debug Bridge Daemon (ADBD). The result of the command execution is sent to the server of the threat actors.

The code for sending an SMS is commented. In fact, it cannot be executed. However, if it is uncommented, then devices with the Android version below 4.2.2 could execute the commands given by malware writers. For newer versions of Android, the ADBD local connection (in the Loopback mode) is forbidden on the device.

Sending an SMS to a regular number does not promise big losses for the victim, but nothing prevents the malware writers from replacing the test number with a premium-rate number.

The first malicious script modification should not cause any big problems for users, even if the threat actors would be able to send an SMS to a short code. Most mobile carriers have the Advice-of-Charge feature, which does not apply any charges for the first SMS to a premium-rate number: one more message with a specific text must be sent. This is impossible to do from within a JavaScript code for the specific case. This is why, most likely, a second modification of the script has appeared.

Script 2: SD-Card File

The second script, in effect, is a dropper. It drops a malicious file from itself onto an SD card.

By resorting to unsophisticated instructions, part of the script body is decrypted. First of all, separators are removed from the string:

Then, the string is recorded onto an SD card into the MNAS.APK file:

The string must be executed. As a result, the created app should be installed onto the system:

However, this code is yet still commented.

Let us review the script in more detail. The script has a check for a specific Android version (it has to be 4).

Obviously, the malware writers know which versions are vulnerable, and they are not trying to run the script on Android 5 or 6.

Just like with the first script, the second has an ADB check at the control center side:

In this case, the check will not affect anything; however, the ADB version is really essential, since not all of the versions support a local connection with ADBD.

We analyzed several modifications of the second script, which allowed us to track the flow of thought of the malware writers. Apparently, their main goal was to deliver the APK file to the victim.

Thus, some earlier script modifications send data about each executed command to the control center:

In this case, the SD card is checked for the MNAS.lock file. If it is not there, then the script tries to create the MNAS.APK file with a zero size by using a touch utility.

In later script modifications, the task of the APK file delivery to the victim was solved by using the ECHO command, which allows to create any file with any content on a device:

As a result of the ECHO command execution, a malicious APK file is created on the SD card.

Trojan

The second script, in the state as we have discovered it, created and wrote a malicious file, which also needed to be executed, onto an SD card. Inasmuch as the dropper script does not contain a Trojan execution mechanism, the task has to be fulfilled by the user.

The APK file dropped from the script can be detected by Kaspersky Lab as Trojan-Spy.AndroidOS.SmsThief.ay. Since the beginning of 2016, we have managed to find four modifications of the Trojan.

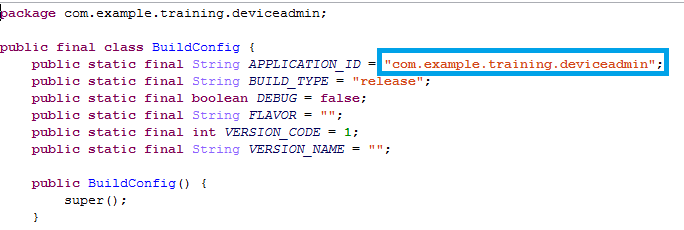

Malware writers use the “example.training” name inside the Trojan code:

At the same time, the malicious file has enough privileges to carry out fully fledged attacks onto the wallet of the victim by sending SMS messages:

The first action that the malicious code does after its execution is requesting administrator rights for the device. After obtaining the rights, it will conceal itself on the application list, thus making it difficult to detect and remove it:

The Trojan will wait for incoming SMS messages. If they fall under given rules, for example, if the come from a number of one of the biggest Russian banks, then these messages will be forwarded at once to the malware writers as an SMS:

Also, the intercepted messages will be forwarded to the server of the threat actors:

Aside from the controlling server, the threat actors use a control number to communicate with the Trojan: the data exchange occurs within SMS messages.

The control number initially exists in the malicious code:

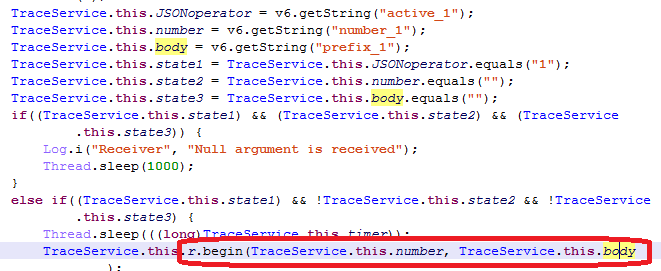

The Trojan awaits specific commands from the control center and in SMS messages from the control number.

A command to change the control number can come from the server of threat actors:

The following commands can come from a control number:

- SEND: send an SMS to an indicated number with indicated text;

- STOP: stop forwarding SMS messages;

- START: start forwarding SMS messages.

For the moment, the functionality of the Trojan is limited to intercepting and sending SMS messages.

Conclusion

The task of carrying out a mass attack on mobile users is solved by infecting a popular resource that harbors a malicious code that is capable of executing any threat actors’ command on an infected mobile device. In case of the attacks described in the article, the emphasis has been placed on devices of Russian users: these devices are old and not up-to-date (notably, Russian domains have been infected).

It is unlikely that the interest of the malware writers towards drive-by attacks on mobile devices will decrease, and they will keep finding methods of carrying out these attacks.

It can be inferred that it is obvious that the attention of malware writers towards publications of research laboratories regarding the topic of Remote Code Execution vulnerabilities will increase, and the attempts to implement attacks by using mobile exploits will persist.

It is also obvious that no matter how enticing publishing is for a 0-day vulnerability, it is worth to refrain from showing detailed exploit examples (Proof of concept). Publishing the mentioned examples most likely will lead to someone creating a fully functional version of a malicious code.

There is a good news for the owners of old devices: our Kaspersky Internet Security solution is capable of protecting your device by tracking changes on the SD card in real time and removing a malicious code as soon as it is written to the SD card. Therefore, our users are protected from the threats known to Kaspersky Lab, which are delivered by the drive-by download method.

Results of PoC Publishing