Contents

- Executive Summary

- Anatomy of the attack

- Timeline

- Targets

- Sinkhole statistics

- KSN + sinkhole data

- С&C information

Executive Summary

In October 2012, Kaspersky Lab’s Global Research & Analysis Team initiated a new threat research after a series of attacks against computer networks of various international diplomatic service agencies. A large scale cyber-espionage network was revealed and analyzed during the investigation, which we called “Red October” (after famous novel “The Hunt For The Red October”).

This report is based on detailed technical analysis of a series of targeted attacks against diplomatic, governmental and scientific research organizations in different countries, mostly related to the region of Eastern Europe, former USSR members and countries in Central Asia.

The main objective of the attackers was to gather intelligence from the compromised organizations, which included computer systems, personal mobile devices and network equipment.

The earliest evidence indicates that the cyber-espionage campaign was active since 2007 and is still active at the time of writing (January 2013).

Besides that, registration data used for the purchase of several Command & Control (C&C) servers and unique malware filenames related to the current attackers hints at even earlier time of activity dating back to May 2007.

Main Findings

Advanced Cyber-espionage Network: The attackers have been active for at least several years, focusing on diplomatic and governmental agencies of various countries across the world.

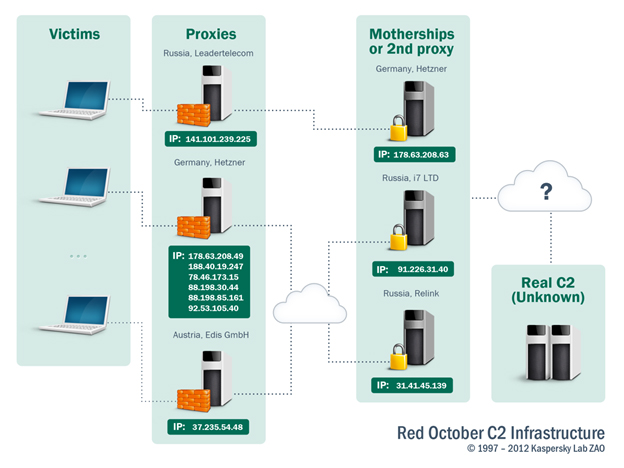

Information harvested from infected networks was reused in later attacks. For example, stolen credentials were compiled in a list and used when the attackers needed to guess secret phrase in other locations. To control the network of infected machines, the attackers created more than 60 domain names and several server hosting locations in different countries (mainly Germany and Russia). The C&C infrastructure is actually a chain of servers working as proxies and hiding the location of the ‘mothership’ control server.

Unique architecture: The attackers created a multi-functional kit which has a capability of quick extension of the features that gather intelligence. The system is resistant to C&C server takeover and allows the attack to recover access to infected machines using alternative communication channels.

Broad variety of targets: Beside traditional attack targets (workstations), the system is capable of stealing data from mobile devices, such as smartphones (iPhone, Nokia, Windows Mobile), enterprise network equipment (Cisco), removable disk drives (including already deleted files via a custom file recovery procedure).

Importation of exploits: The samples we managed to find were using exploit code for vulnerabilities in Microsoft Word and Microsoft Excel that were created by other attackers and employed during different cyber attacks. The attackers left the imported exploit code untouched, perhaps to harden the identification process.

Attacker identification: Basing on registration data of C&C servers and numerous artifacts left in executables of the malware, we strongly believe that the attackers have Russian-speaking origins. Current attackers and executables developed by them have been unknown until recently, they have never related to any other targeted cyberattacks.

Anatomy of the attack

General description

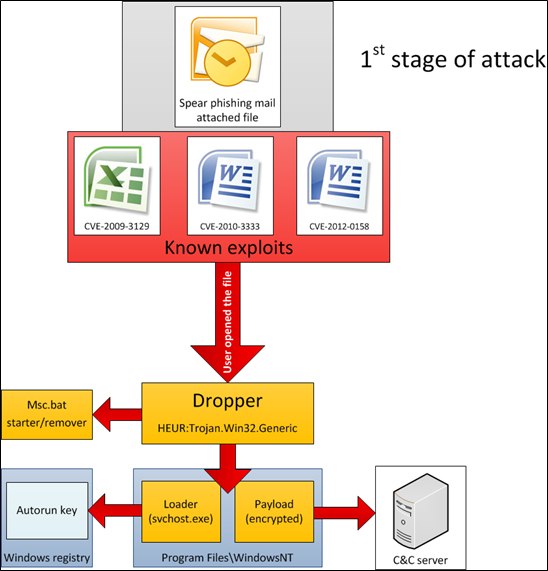

These attacks comprised of the classical scenario of specific targeted attacks, consisting of two major stages:

- Initial infection

- Additional modules deployed for intelligence gathering

The malicious code was delivered via e-mail as attachments (Microsoft Excel, Word and, probably PDF documents) which were rigged with exploit code for known security vulnerabilities in the mentioned applications. In addition to Office documents (CVE-2009-3129, CVE-2010-3333, CVE-2012-0158), it appears that the attackers also infiltrated victim network(s) via Java exploitation (known as the ‘Rhino’ exploit (CVE-2011-3544).

Right after the victim opened the malicious document or visit malicious URL on a vulnerable system, the embedded malicious code initiated the setup of the main component which in turn handled further communication with the C&C servers.

Next, the system receives a number of additional spy modules from the C&C server, including modules to handle infection of smartphones.

The main purpose of the spying modules is to steal information. This includes files from different cryptographic systems, such as “Acid Cryptofiler”, (see https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acid_Cryptofiler) which is known to be used in organizations of European Union/European Parliament/European Commission since the summer of 2011. All gathered information is packed, encrypted and only then transferred to the C&C server.

Step-by-step description (1st stage)

During our investigation we couldn’t find any e-mails used in the attacks, only top level dropper documents. Nevertheless, based on indirect evidence, we know that the e-mails can be sent using one of the following methods:

- Using an anonymous mailbox from a free public email service provider

- Using mailboxes from already infected organizations

E-mail subject lines as well as the text in e-mail bodies varied depending on the target (recipient). The attached file contained the exploit code which activated a Trojan dropper in the system.

We have observed the use of at least three different exploits for previously known vulnerabilities: CVE-2009-3129 (MS Excel), CVE-2010-3333 (MS Word) and CVE-2012-0158 (MS Word). The first attacks that used the exploit for MS Excel started in 2010, while attacks targeting the MS Word vulnerabilities appeared in the summer of 2012.

As a notable fact, the attackers used exploit code that was made public and originally came from a previously known targeted attack campaign with Chinese origins. The only thing that was changed is the executable which was embedded in the document; the attackers replaced it with their own code.

The embedded executable is a file-dropper, which extracts and runs three additional files.

%TEMP%MSC.BAT

%ProgramFiles%WINDOWS NTLHAFD.GCP (<- This file name varies)

%ProgramFiles%WINDOWS NTSVCHOST.EXE

MSC.BAT file has the following contents:

chcp 1251

:Repeat

attrib -a -s -h -r “%DROPPER_FILE%”

del “%DROPPER_FILE%”

if exist “%DROPPER_FILE%” goto Repeat

del “%TEMP%msc.bat”

Another noteworthy fact is in the first line of this file, which is a command to switch the codepage of an infected system to 1251. This is required to address files and directories that contain Cyrillic characters in their names.

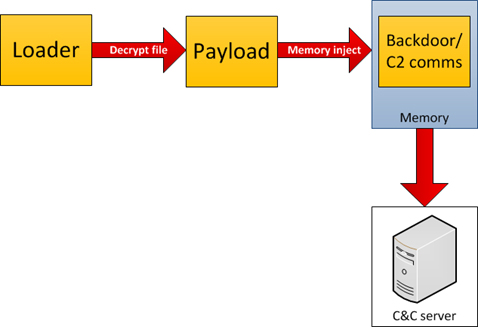

The “LHAFD.GCP” file is encrypted with RC4 and compressed with the “Zlib” library. This file is essentially a backdoor, which is decoded by the loader module (svchost.exe). The decrypted file is injected into system memory and is responsible for communication with the C&C server.

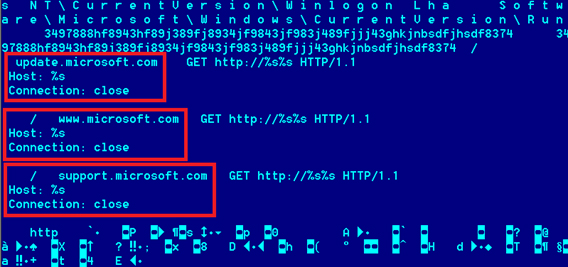

On any infected system, every major task is performed by the main backdoor component. The main component is started only after its loader (“svchost.exe”) checks if the internet connection is available. It does so by connecting to three Microsoft hosts:

- update.microsoft.com

- www.microsoft.com

- support.microsoft.com

Figure – Hosts used to validate internet connection

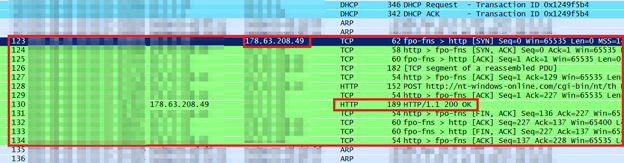

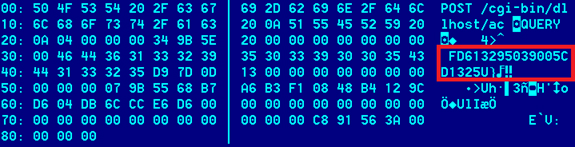

After the Internet connection is validated, the loader executes the main backdoor component that connects to its C&C servers:

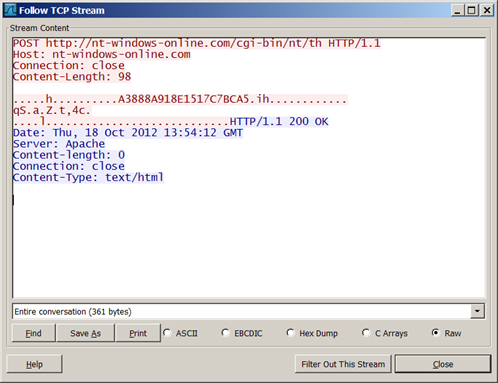

Capture of malware’s communication with the C2

The connections with the C&C are encrypted – different encryption algorithms are used to send and receive data.

Encrypted communication with the C2

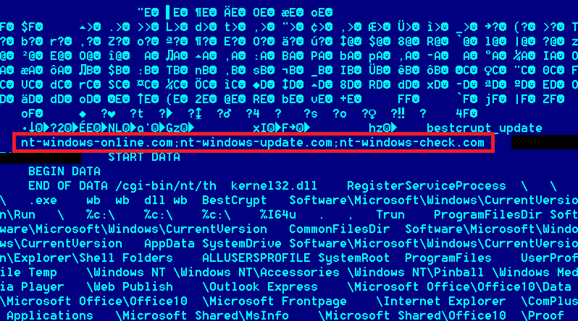

During our investigation, we found more than 60 different command-and-control domains. Each malware sample contains three such domains, which are hardcoded inside the main backdoor component:

Hardcoded C2 domains inside backdoor

Step-by-step description (2nd stage)

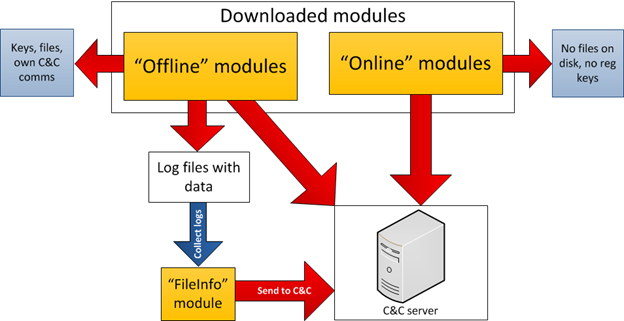

After a connection with the C&C server is established, the backdoor starts the communication process, which leads to the loading of additional modules. These modules can be split into two categories: “offline” and “online”.

The main difference between these categories is their behavior on the infected system:

- “Offline”: exists as files on local disk, capable of creating its own system registry keys, local disk log files, and may communicate with C&C servers on their own.

- “Online”: exists only in system memory and is never saved to local disk, do not create registry keys, all logs are also kept in memory instead of local disk and sends the result of work to the C&C server using own code.

There is a notable module among all others, which is essentially created to be embedded into Adobe Reader and Microsoft Office applications. The main purpose of its code is to create a foolproof way to regain access to the target system. The module expects a specially crafted document with attached executable code and special tags. The document may be sent to the victim via e-mail. It will not have an exploit code and will safely pass all security checks. However, like with exploit case, the document will be instantly processed by the module and the module will start a malicious application attached to the document.

This trick can be used to regain access to the infected machines in case of unexpected C&C servers shutdown/takeover.

Timeline

We have identified over 1000 different malicious files related to over 30 modules of this Trojan kit. Most of them were created between May 2010 and October 2012.

There were 115 file-creation dates identified which are related to these campaigns via emails during the last two and a half years. Concentration of file creation dates around a particular day may indicate date of the massive attacks (which was also confirmed by some of our side observations):

Year 2010

- 19.05.2010

- 21.07.2010

- 04.09.2010

Year 2011

- 05.01.2011

- 14.03.2011

- 05.04.2011

- 23.06.2011

- 06.09.2011

- 21.09.2011

Year 2012

- 12.01.2012

Below is a list of sample attachment filenames that were sent to some of the victims:

| File name: |

| Katyn_-_opinia_Rosjan.xls |

| FIEO contacts update.xls |

| spisok sotrudnikov.xls |

| List of shahids.xls |

| Spravochnik.xls |

| Telephone.xls |

| BMAC Attache List – At 11 Oct_v1[1].XLS |

| MERCOSUR_Imports.xls |

| Cópia de guia de telefonos (2).xls |

| Programme de fetes 2011.xls |

| 12 05 2011 updated.xls |

| telefonebi.xls |

Targets

We used two approaches to identify targets for these attacks. First, we used the Kaspersky Security Network (KSN) and then we set up our own sinkhole server. The data received using two independent ways was correlating and this confirmed objective findings.

KSN statistics

The attackers used already detected exploit codes and because of this, in the beginning of the research we already had some statistics of detections with our anti-malware software. We searched for similar detections for the period of 2011-2012.

That is how we discovered more than 300 unique systems, which had detected at least one module of this Trojan kit.

| RUSSIAN FEDERATION | 35 |

| KAZAKHSTAN | 21 |

| AZERBAIJAN | 15 |

| BELGIUM | 15 |

| INDIA | 15 |

| AFGHANISTAN | 10 |

| ARMENIA | 10 |

| IRAN | 7 |

| TURKMENISTAN | 7 |

| UKRAINE | 6 |

| UNITED STATES | 6 |

| VIET NAM | 6 |

| BELARUS | 5 |

| GREECE | 5 |

| ITALY | 5 |

| MOROCCO | 5 |

| PAKISTAN | 5 |

| SWITZERLAND | 5 |

| UGANDA | 5 |

| UNITED ARAB EMIRATES | 5 |

| BRAZIL | 4 |

| FRANCE | 4 |

| GEORGIA | 4 |

| GERMANY | 4 |

| JORDAN | 4 |

| MOLDOVA | 4 |

| SOUTH AFRICA | 4 |

| TAJIKISTAN | 4 |

| TURKEY | 4 |

| UZBEKISTAN | 4 |

| AUSTRIA | 3 |

| CYPRUS | 3 |

| KYRGYZSTAN | 3 |

| LEBANON | 3 |

| MALAYSIA | 3 |

| QATAR | 3 |

| SAUDI ARABIA | 3 |

| CONGO | 2 |

| INDONESIA | 2 |

| KENYA | 2 |

| LITHUANIA | 2 |

| OMAN | 2 |

| TANZANIA | 2 |

Countries with more than one infections

Once again, this is based on data from Kaspersky AV products. Apparently, real number and list of victim names is much larger than mentioned above.

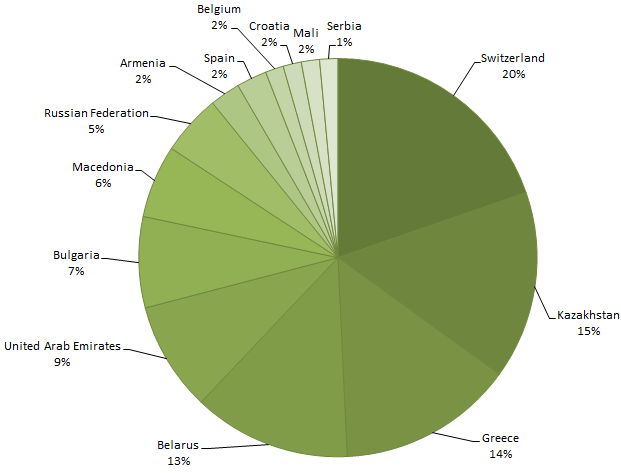

Sinkhole statistics

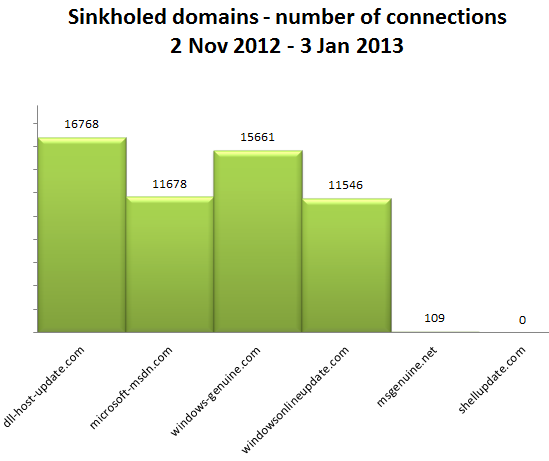

During our analysis, we uncovered more than 60 different domains used by different variants of the malware.

Out of the list of domains, several were expired so we registered them to evaluate the number of victims connecting to them.

The following domains have been registered and sinkholed by Kaspersky Lab:

| Domain | Date sinkholed |

| shellupdate.com | 5-Dec-2012 |

| msgenuine.net | 19-Nov-2012 |

| microsoft-msdn.com | 5-Nov-2012 |

|

windowsonlineupdate.com dll-host-update.com windows-genuine.com |

2-Nov-2012 |

All the sinkholed domains currently point to “95.211.172.143”, which is Kasperskys’ sinkhole server.

During the monitoring period (2- Nov 2012 – 10 Jan 2013), we registered over 55,000 connections to the sinkhole. The most popular domain is “dll-host-update.com”, which is receiving most of the traffic.

From the point of view of country distribution of connections to the sinkhole, we have observed victims in 39 countries, with most of IPs being from Switzerland. Kazakhstan and Greece follow next.

Interestingly, when connecting to the sinkhole, the backdoors submit their unique victim ID, which allows us to separate the multiple IPs per victims.

Based on the traffic received to our sinkhole, we created the following list of unique victim IDs, countries and possible profiles:

| Victim ID | Country | Victim profile |

| 0706010C1BC0B9E5B702 | Kazakhstan | Gov research institute |

| 0F746C2F283E2FACE581 | Kazakhstan | ? |

| 150BD7E7449C42C66ED1 | Kazakhstan | ? |

| 15B7400DBC4975BFAEF6 | Austria | ? |

| 24157B5D2CD0CA8AA602 | UAE | ? |

| 3619E36303A2A56DC880 | Russia | Foreign Embassy |

| 4624C55DEF872FBF2A93 | Spain | ? |

| 4B5181583F843A904568 | Spain | ? |

| 4BB2783B8AEC0B439CE8 | Switzerland | ? |

| 5392032B24AAEE8F3333 | Kazakhstan | ? |

| 569530675E86118895C4 | Pakistan | ? |

| 57FE04BA107DD56D2820 | Iran | Foreign Embassy |

| 5D4102CD1D87417FF93B | Russia | Gov research institute |

| 5E65486EF8CC4EE4DB5B | Japan | Foreign Trade Commission |

| 6127D685ED1E72E09201 | Kazakhstan | ? |

| 6B9AFF89A02958C79C17 | Ireland | Foreign Embassy |

| 6D97B24C08DD64EEDE03 | Czech Republic | ? |

| 7B14DE85C80368337E87 | Turkey | ? |

| 89BF96469244534DC092 | Belarus | Gov research institute |

| 8AA071A22BEDD8D8EC13 | Moldova | Government |

| 8C58407030570D3A3F52 | Albania | ? |

| 947827A169348FB01E2F | Bosnia and Herzegovina | ? |

| B34C94D561B348EAC75D | Switzerland | ? |

| B49FC93701E7B7F83C44 | Belgium | ? |

| B6E4946A47FC3963ABC1 | Kazakhstan | Energy research group |

| C978C25326D96C995038 | Russia | ? |

| D48A783D288DC72A702B | Kazakhstan | Aerospace |

| DAE795D285E0A01ADED5 | Russia | Trading company |

| DD767EEEF83A62388241 | Russia | Gov research institute |

In some cases, it is possible to create a profile of the victim based on the IP address; in most of the cases, however, the identity of the victim remains unknown.

KSN + sinkhole data

Some of the victim organizations were identified using IP addresses and public WHOIS information or remote system names.

Most “interesting” out of those are:

| Algeria – Embassy |

| Afghanistan – Gov, Military, Embassy, |

| Armenia – Gov, Embassy |

| Austria – Embassy |

| Azerbaijan – Oil/Energy, Embassy, Research, |

| Belarus – Research, Oil/Energy, Gov, Embassy |

| Belgium – Embassy |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina – Embassy |

| Botswana – Embassy |

| Brunei Darussalam – Gov |

| Congo – Embassy |

| Cyprus – Embassy, Gov |

| France – Embassy, Military |

| Georgia – Embassy |

| Germany – Embassy |

| Greece – Embassy |

| Hungary -Embassy |

| India – Embassy |

| Indonesia – Embassy |

| Iran – Embassy |

| Iraq – Gov |

| Ireland – Embassy |

| Israel – Embassy |

| Italy -Embassy |

| Japan – Trade, Embassy |

| Jordan – Embassy |

| Kazakhstan – Gov, Research, Aerospace, Nuclear/Energy, Military |

| Kenya – Embassy |

| Kuwait – Embassy |

| Latvia – Embassy |

| Lebanon – Embassy |

| Lithuania – Embassy |

| Luxembourg – Gov |

| Mauritania – Embassy |

| Moldova – Gov, Military, Embassy |

| Morocco – Embassy |

| Mozambique – Embassy |

| Oman – Embassy |

| Pakistan – Embassy |

| Portugal – Embassy |

| Qatar – Embassy |

| Russia – Embassy, Research, Military, Nuclear/Energy |

| Saudi Arabia – Embassy |

| South Africa – Embassy |

| Spain – Gov, Embassy |

| Switzerland – Embassy |

| Tanzania – Embassy |

| Turkey – Embassy |

| Turkmenistan – Gov, Oil/Energy |

| Uganda – Embassy |

| Ukraine – Military |

| United Arab Emirates – Oil/Energy, Embassy, Gov |

| United States – Embassy |

| Uzbekistan – Embassy |

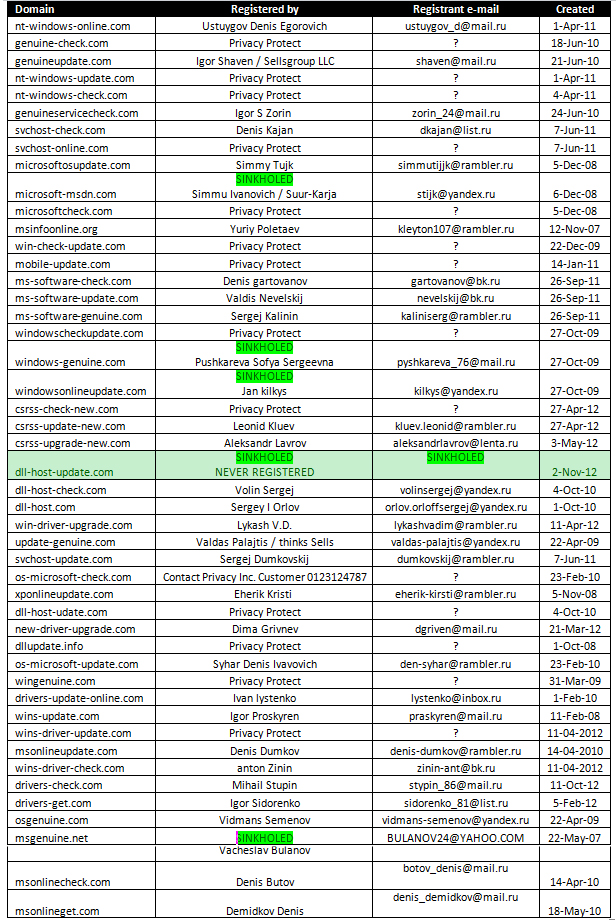

С&C information

A list of the most popular domains used for command and control can be found below:

Interestingly, although the domain “dll-host-update.com” appears in one of the malware configurations, it had not been registered by the attackers. The domain has since been registered by Kaspersky Lab on Nov 2nd, 2012 to monitor the attacker’s activities.

Another interesting example is “dll-host-udate.com” – the “udate” part appears to be a typo.

All the domains used by attackers appear to have been registered between 2007-2012. The oldest known domain was registered in Nov 2007; the newest on May 2012.

Most of the domains have been registered using the service “reg.ru”, but other services such as “webdrive.ru”, “webnames.ru” or “timeweb.ru” have been used as well.

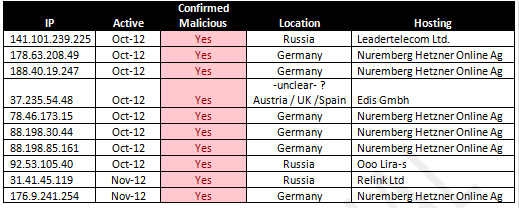

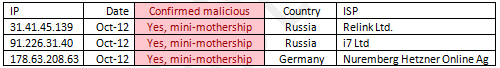

During our monitoring, we observed the domains pointing to several malicious webservers. A list of servers with confirmed malicious behavior can be found below.

In total, we have identified 10 different servers which exhibited confirmed malicious behavior. Most of these severs are located in Germany, at Hetzner Online Ag.

During our analysis, we were able to obtain an image of one of the command-and-control servers. The server itself proved to be a proxy, which was forwarding the request to another server on port 40080. The script responsible for redirections was found in /root/scp.pl and relies on the “socat” tool for stream redirection.

By scanning the Internet for computers with port 40080 open, we were able to identify three such servers in total, which we call “mini-motherships”:

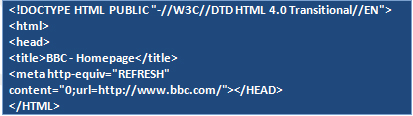

Connecting to these hosts on port 40080 and fetching the index page, we get the following standard content which is identical in all C&Cs:

Fetching the index info (via HTTP “HEAD”) for these servers, reveals the following:

|

curl -I –referer “http://www.google.com/” –user-agent “Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 6.0; Windows NT 5.1)” http://31.41.45.139:40080 HTTP/1.1 200 OK |

|

curl -I –referer “http://www.google.com/” –user-agent “Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 6.0; Windows NT 5.1)” http://178.63.208.63:40080 HTTP/1.1 200 OK |

It should be noted that the “last modified” field of the pages points to the same date: Tue, 21 Feb 2012 09:00:41 GMT. This is important and probably indicates that the three known mini-motherships are probably just proxies themselves, pointing to the same top level “mothership” server.

This allows us to draw the following diagram of the C&C infrastructure as of November 2012:

For the Command and Control servers, the various generations of the backdoor connect to different scripts:

| Domain | Script location |

| nt-windows-update.com, nt-windows-check.com, nt-windows-online.com |

/cgi-bin/nt/th /cgi-bin/nt/sk |

| dll-host-update.com | /cgi-bin/dllhost/ac |

| microsoft-msdn.com |

/cgi-bin/ms/check /cgi-bin/ms/flush |

| windows-genuine.com |

/cgi-bin/win/wcx /cgi-bin/win/cab |

| windowsonlineupdate.com | /cgi-bin/win/cab |

For instance, the script “/cgi-bin/nt/th” is being used to receive commands from the command-and-control server, usually in the form of new plugins to run on the victim’s computer. The “/cgi-bin/nt/sk” script is called by the running plugins to upload stolen data and information about the victim.

When connecting to the C&C, the backdoor identifies itself with a specific string which includes a hexadecimal value that appears to be the victim’s unique ID. Different variants of the backdoor contain different victim IDs. Presumably, this allows the attackers to distinguish between the multitudes of connections and perform specific operations for each victim individually.

For instance, a top level XLS dropper presumably used against a Polish target, named “Katyn_-_opinia_Rosjan.xls” contains the hardcoded victim ID “F50D0B17F870EB38026F”. A similar XLS named “tactlist_05-05-2011_.8634.xls / EEAS New contact list (05-05-2011).xls” possibly used in Moldova contains a victim ID “FCF5E48A0AE558F4B859”.

Part 2 of this paper will cover malware modules and provide more technical details about their operation.

“Red October” Diplomatic Cyber Attacks Investigation

Sol

necesito acceder a la segunda parte del informe de Rocra para realizar un trabajo académico, por favor.

Securelist

¡Hola, Sol!

Está aquí: https://securelist.com/red-october-part-two-the-modules/57645/