Kaspersky has repeatedly investigated security issues related to IoT technologies (for instance, here, or here). Earlier this year our experts have even gained foothold in the security of biomechanical prosthetic devices. The same implies to smart car security: our own research has indicated that there are number of issues—look here or here.

This year, we decided to continue our tradition of small-scale experiments with security of connected devices but focused on the automotive-related topic. The topic has retained its importance through the years, and as our own research into the subject has revealed, there are security issues in the market, since the vehicles are becoming smarter and more connected—and more exposed. But apart from that, there is a whole industry of aftermarket devices for the improvement of driving experience, from car scanners to various tuning gadgets. This angle was not examined separately, so we randomly took several different automotive connected devices and reviewed their security setup. Whilst it could hardly be called an investigation, this exercise allowed us to get a first look at security issues these suffer from.

We looked at the following devices: a couple of auto scanners, a dashboard camera, a GPS tracker, a smart alarm system, and a pressure and temperature monitoring system.

Scanning tool OBD dongle: secured exposure

The civil automotive diagnostics market is literally flooded with various wired and wireless, small and large devices that connect to the OBD2 diagnostic connector. They are basically sticks that are plugged into the vehicle and provide key driving dynamics data. Some of these devices are autonomous, and some depend on computers or mobile phones. They offer extensive recording and analysis options: the data includes engine speed, temperature, turbocharging, oil pressure, etc.

There are also applications that allow not only to read, but also to program the “brain” of the car, for example, to reset the “check engine” light. Use of these applications and making changes to vehicle operation through these can carry significant risks. In addition to the risk of damage to the car due to an operator error, there is a risk of an intruder intercepting control over the device. Of course, if the device is wired, then such risks are minimized, but if wireless—with the data from the diagnostic port transmitted via Bluetooth or WiFi—the risks of interception increase. Hence, there is an interest in how well the manufacturers of such devices have taken care of security.

The device that landed in our hands was developed by a German manufacturer and marketed under the brand of a well-known carmaker. For security reasons, we will not disclose the name.

The device is positioned as a racing logger that can record a video of the race on the track and superimpose over it telemetry data obtained from the car: speed, engine output, boost and so on.

The device works in conjunction with an iOS- or Android-powered smartphone connected via Bluetooth. All data is displayed on the screen of the smartphone. Ah, here we go. Since we decided to understand whether the use of this device carries any risk for the user, the Bluetooth connection is a good start.

Our initial analysis has shown that the device completely refused to work with the iPhone: the smartphone just could not see it. The problem may have been the firmware—this remained a mystery. Thus, all further experiments were carried out on an Android device.

In order to start working with the device, one needs to go through a pairing procedure. No passwords are required for this, anyone can pair anytime. This is a bad thing.

However, once the device is paired, the potential wrongdoer with his own device would need the serial number to connect the dongle on his own. The number is printed on the stick, so he would need physical access to it. Would he not?

In essence, that is it. The serial number has a format similar to “000780d9b826”. And if you write that as “00:07:80:d9:b8:26”, you get the MAC address of the Bluetooth adapter used in the dongle. So basically, you can find out the serial number while performing Bluetooth scanning in the vicinity of the working dongle. And here is the funny thing: this serial number / MAC address is the password to the dongle at the same time.

So, the dongle is broadcasting across the surrounding space and, as per the Bluetooth standard, disclosing its MAC address to the public, along with the access key. This means that virtually anyone can get access to the dongle by installing a simple Bluetooth scanner on a smartphone and finding a device with the name OBD STICK within the range. That’s all.

The bad news for the hacker is that the application itself does not allow controlling the car, only analyzing data from it. What if we set up a connection to the dongle from another application? We have tried this approach with a couple of other applications from Google Play.

According to the developers of the applications, there is quite a long list of functions that can mess with car drive dynamics data. We could not test this as, although the application connects to the dongle, it cannot read data from the CAN bus. The application is programmed to interact with OBD dongles via its specific protocol, while the examined device has its own, different protocol.

Dongles of this kind are normally built around the ELM327 chip, the most popular microcontroller in the market. Its main purpose is to process signals from the CAN bus and provide information to the consumer via an RS-232 interface, for example, a Bluetooth adapter—or USB adapter, if the connection is a wired one. The interface will transmit data to the smartphone via radio signal, and the phone will pass it on to the application. How to process the signals, receive these from the CAN bus or to transmit them there, in what form they are transmitted to the consumer—these are driven by the firmware, recorded into the ROM of the microcontroller in the factory. A completely different AT90CAN128-16MU microcontroller and a completely different firmware are used in the device being examined.

Thus, the reasonable question would be, whether it is possible to modify the firmware of the controller to add new capabilities. We found that there is an option to update dongle firmware in the application. Our research into the application code has revealed that:

- The application can download firmware from the developer’s website via an insecure HTTP connection.

- The firmware comes with the application itself.

All in all, we can get our hands on the firmware for further analysis and modification. So, do we finally have it? Unfortunately, not—the firmware is encrypted. This is no surprise and a smart move on the part of the vendor, since this protects the most delicate part of device operation: the data exchange protocol between the car and the dongle. Thus, there are only two ways to get the firmware: to request from the vendor or invest enormous effort into analyzing signals from the car. While this is doable, it if definitely is out of scope for our experiment.

To recap, we can say that, despite several minor insecurities, there is not much a malicious user can do with the device, all thanks to firmware encryption. Still, anyone can get access to the device and monitor the drive dynamics data. And it is also theoretically possible that a malicious user is persistent enough to get physical access to the firmware and reprogram it.

In order to make the device more secure, we would advise providing it with a unique access key and using that key for Bluetooth pairing. That way, the Bluetooth traffic will not be accessible to interception. And one recommendation for all who have already become a proud owner of this device: use it only on the race track and do not forget to pull the device from the OBD2 port after the race day.

Tire pressure and temperature monitoring system: a storm in a teacup

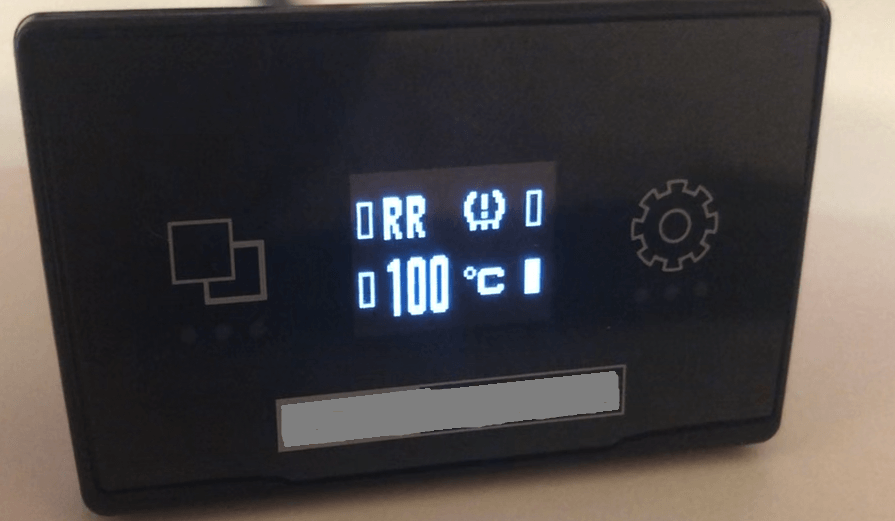

The other device we got our hands on was basically a toolset for monitoring tire pressure and temperature. It includes four sensors, installed directly in the car wheels, a screen located in the car interior, and a control unit. The sensors transmit radio signal to the unit, which passes the information to the screen. The latter displays the following:

- the current tire pressure;

- the temperature of the wheels.

The user can also toggle the unit of temperature between Celsius and Fahrenheit, choose from pounds per square inch (psi), Bar and Pascal for pressure display, and connect a new sensor when one breaks down. If the pressure drops to a critical point, the control unit emits a loud squeak. The same occurs when the pressure or the temperature in the wheel reach a high level. We decided to test whether it is possible to simulate a pressure drop or overheating of a wheel, thus forcing the driver to stop.

As mentioned, the sensors pass information to the control unit via radio signal on a frequency permitted for civil use. In order to intercept the radio signal, any RTL-SDR receiver that can be had for a couple of dollars will work. However, such devices are capable of reception only—they will not be able to transmit signal. To do this, one needs a complete SDR device, with both receiving and transmitting capability. We decided to use one for our security test.

When we turned the system on, it did not show any signs of activity, except for indicating an absence of connection with the sensors.

The system ran for ten minutes in that mode, then started to signal an absence of communication with the pressure sensors. We decided to point our receiver to the required frequency.

Nothing. Neither sensors, nor the system itself showed any sign of activity. There could be three reasons: the sensors were not charged, the system was based on a gyroscope and the sensors only worked when the wheels were spinning, or the sensors were activated when the pressure inside was higher than the ambient pressure. To find out the exact reason, we needed to tinker with the sensors.

The third reason turned out to be the real one: we used a syringe to create a higher pressure in the sensors, and they showed signs of activity.

The intercepted signals provided the specific frequency the system ran on. Using that, we recorded the signals with a receiver. Sensors analyze tire pressure and temperature, encode that information into bytes and transmit it via the modulator in the form of radio signals. We analyzed these via a special program that normally shows recorded signals. What we did was basically grab grabbed the modulated signals and decode those back into bytes.

Here it is. When zoomed, the visual recording looks very much like Frequency Shift Keying (FSK) modulation (a digital modulation technique where the frequency of the carrier signal varies according to digital signal changes):

This stage allowed us to recognize the transmitted bits, as bottom and top strokes are basically “1” or “0”, indicating presence or absence of signal. Thus, the recorded visual signal can be presented in the form of bits as follows:

|

1 |

0101010101010101010101010101011010011001011001100101010101011010100110100110010110101010011010100110100101011001011001011010100101010101011001010110101010010110 |

Now, we need to find out the parameters of signal transmission. The program shows that the symbol rate is 19400 Bd.:

We assumed that the system is using Manchester code, as it is the most widespread one. It is basically an agreement on how to digitally encode radio signal, a line code in which the encoding of each data bit is either low, then high—or high, then low.

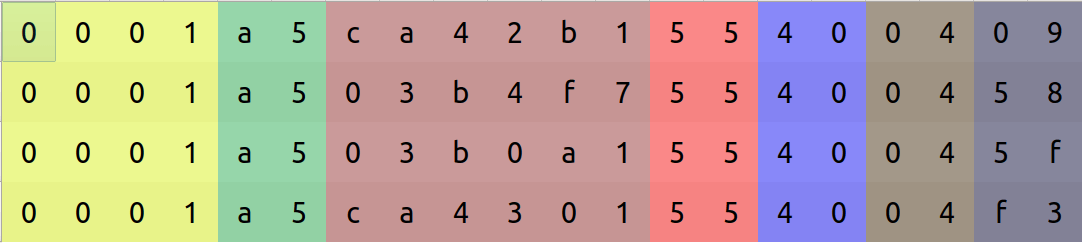

There are two encoding conventions: when 0 is expressed through a low-to-high transition and 1 is expressed through a high-to-low transition (Thomas convention), and when the reverse is true (IEEE 802.3 convention). We manipulated the syringe to create a higher pressure in the sensors for further analysis. For our own convenience, we shifted the recorded data into a hexadecimal positional numeral system. The signals looked as follows:

FF FE 5A FC 4B 08 9D B1 FB 86

The seventh, eighth and tenth bytes, marked in red, showed changes when sensors were pressed. For a integrity check, we converted some of the bytes into the decimal system, but the figures turned out to be too big to represent a level of pressure.

The system manual indicated that the maximum permissible pressure was 6 bars. The average syringe produces approximately 2.2 bars. Our further calculations have revealed that the seventh byte (62) stands for around 2.254 in the Thomas convention. This was very close, so we concluded that the seventh byte was responsible for pressure data. This also allowed us to identify out the convention used in the system encoding.

After collecting more and more signal, we revealed a number of regularities in the recording that led us to the following informed guess on what each byte stands for.

| 00 | Preamble |

| 01 | |

| A5 | Synchronization byte |

| 03 | Sensors serial number |

| B4 | |

| F7 | |

| 62 | Pressure |

| 4E | ??? |

| 04 | ??? |

| 79 | Checksum |

We were able to notice that the eighth byte changed rarely and by a very small value. Since we were testing the sensor inside a room with a stable temperature, it was reasonable to guess what that byte stood for. As we now knew the encoding logic, we could try to test that hypothesis. According to the system manual, the operating temperature was between -40 and +125 degrees Celsius.

However, we assumed that the system used the Kelvin scale, so we decided to shift our metric to Kelvins since it does not use “0”. Our calculations showed that the eighth byte (4E) stood for 37 degrees Celsius which seemed quite credible. Thus, we had now identified three meaningful byte columns: tire pressure, temperature and serial number.

With all that in mind, we prepared four packages of byte data and set up the transmitter:

The red column, for instance, stands for 2 bars of pressure and the blue one, for 24 degrees Celsius. And it worked! We could now proceed to hacking the system. For the second iteration, we changed the values in one of the columns to simulate the temperature of the rear right wheel.

That worked as well: the control unit indicated an overheating of one hundred degrees Celsius!

So, what can a hacker use all of that for?

First of all, for a successful attack, he needs to know the unique serial number of each wheel. He can obtain that information the same way we did: from the transmitted signal. So, the hacker can simply approach the targeted vehicle with a receiver, press repeatedly on the tires and then decode the signal. After that, he should be able to send fake packages of data. But this would be a difficult task: the hacker would need to transmit a signal from the car with a constantly directed antenna to the victim’s car while driving, as once the signal was lost, the receiver in the car would immediately accept the signal from the original sensors and stop signaling problems.

Therefore, while our research indicated that there was indeed a way to mess with the system we purchased, the simulated attack is too resource-intensive. It is much cheaper and easier to use a different way of forcing the owner to leave the car:

Overall, one can call the device vulnerable due to the possibility of intercepting and decoding its radio signal. However, the functionality of this device is so limited that its owners can rest easy.

Another dongle: does the wire count?

As said above, there are a lot of devices that can talk with a vehicle’s smart components via an OBD2 connector. While the wireless connections have proven to have insecurities, we have also decided to examine their wired peers for diversity reasons. The device we purchased turned out to be an error code reader.

It also connected to the car by means of an OBD that included multiple physical channels for communication with the vehicle’s internals. However, in reality, an error code reader only need to support one channel, which is a CAN bus. Even though in our case this interface was used only for error code reading, its actual functionality depended on vehicle design and could be much broader, including even the vehicle’s Electronic Control Units (ECUs) firmware update.

We decided to take a closer look at our reader and analyze how it can communicate with the vehicle.

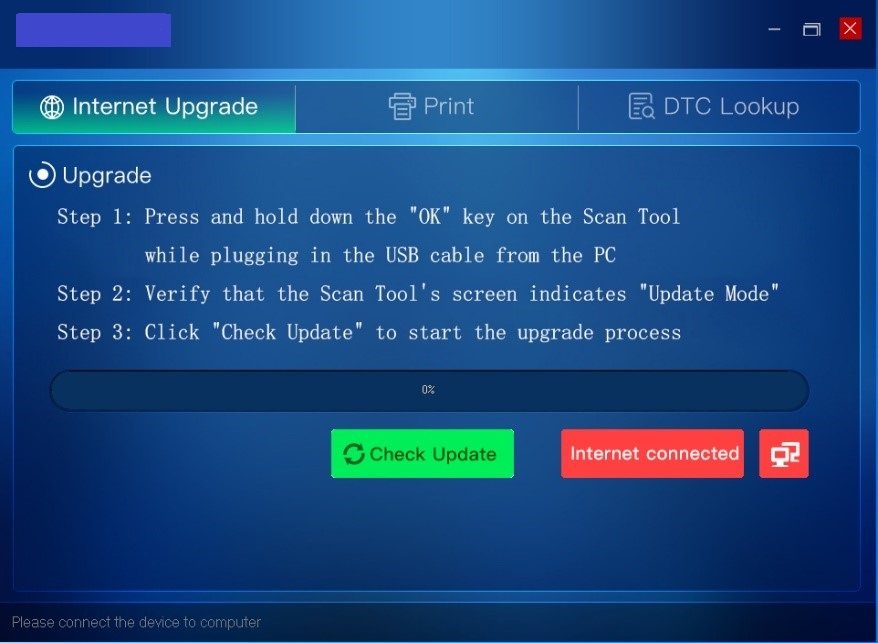

Our device’s communication scheme is rather simple. In addition to OBD, it has only one USB interface, which is used for firmware upgrades and communication with a PC.

The vendor put a lot of effort into protecting the firmware against analysis. To start with, files with the latest firmware cannot be downloaded from the Internet via a direct link. The firmware upgrade process is performed by means of a special software utility.

We did not find anything that resembled firmware in the software distribution, so we made the assumption that the firmware had to be somehow downloaded from the Internet. We analyzed the network traffic that was sent by the software during the firmware update process and found out that the firmware was transferred via regular HTTP requests. That means that it is possible to download the latest firmware from a web browser by copying the request used by the utility. Once downloaded, the firmware was sent to the device via a proprietary protocol implemented over the USB connection. We investigated the protocol and determined the format of all commands used for writing code or data to a specific address. We also wrote a script capable of communicating with the device via the protocol.

And here comes the second protection measure employed by the vendor: encryption. The firmware consists of two parts, stored in two separate files, and both of those are encrypted. This structure is due to the device hardware design.

The major components of the device are a microcontroller, equipped with a relatively small amount of internal flash memory for firmware storage, and a separate external flash chip for storing bigger amounts of requisite data. The two firmware files contain data for the external and internal flash storage, respectively.

As we were unable to analyze the firmware downloaded from the Internet, we tried to download it directly from the device after an update in hope that it was stored in an unencrypted form. We failed with the firmware part that was stored in the internal flash, as the microcontroller had its debug interface blocked, and it was not possible to access the internal flash memory.

However, we did partially succeed as we were able to dump an image of the external flash. The image contained only the device’s configuration and no code, but all data on the flash chip were stored in the unencrypted form. We assumed that, as the device decrypted external flash data during the firmware update, it could also decrypt the internal flash data. And both the decryption algorithm and key could be the same for both firmware parts. We tried to write the internal part of the firmware to the external flash, and as our assumption proved correct, as we found the decrypted code in the external flash afterwards.

We found that the internal flash was only partially written to during the firmware update. Some of the code remained the same, at least during an update to the firmware version we were analyzing. However, there was still a possibility to investigate all the code included in the firmware update package.

Thus, we were able to get our hands on the decrypted part of the firmware and to write it down to the external chip with the help of a pre-written script that implemented the vendor’s software protocol. Theoretically, this could give us a way to tamper with the device by adding arbitrary code to the chip through physical access via the USB protocol.

The latter could allow us to reprogram the device, forcing it to write down all parts of its firmware to the external chip. With a complete image available, we would be able to search for various vulnerabilities. The problem is that the device has so little memory that it would not be able to perform anything but error reading and logging.

So, the situation here is clear, just like with mobile phones and smartphones: fewer capabilities and simpler connectivity means fewer insecurities. However, vendors are still better off encrypting all crucial parts of their data, such as firmware—even if their product is wired.

Smart alarm systems for cars: mobility as insecurity

Another device came from a well-known Russian vendor that produces automotive security systems. This particular device that we examined was a car security system capable of controlling opening of the doors and starting of the engine. Obviously, an attacker assuming control over the system would put a big question mark over the car’s future. Interestingly enough, the vendor guarantees that it is impossible to hijack the car with the system installed. Let us see whether that is a valid statement.

The system is basically a control unit installed inside the car, in a special hard-to-reach section. This is normally done in auto repair shops. Once installed, the system is then paired with the owner’s smartphone. Initial analysis showed that there were three ways to control the system:

- With keychains, of which the package includes two: a simple one that can open the door and trunk and an advanced one with a display that shows status information;

- Discreetly, via a paired smartphone;

- Via Bluetooth, from an Android-powered smartphone.

The keychains interact with the alarm system at a frequency of 868 megahertz. It is not possible to intercept anything because the information is encrypted, and we would only see a useless set of data, which could take years to decrypt. We believe it is unlikely that a malicious user would go for it. Our search in the Darknet was also of no help, as we were unable to find an implemented hack for this vector. Therefore, the manufacturer has implemented an excellent product within the first attack vector.

The other way to attack the system was by infecting the original paired phone. We decided to test this scenario.

When started, the application requests neither a login, nor a password. The interaction between the mobile phone and the security system takes place directly, without any unlocking pattern. This is very bad news: if a hacker steals an unlocked phone, he can then steal the car as well, simply by commanding it to open a door. But we decided to go further.

There are many ways to attack an Android phone and then interfere with its functioning. We decided to try the Android Accessibility service vector. This is a service for people with disabilities that allows managing of all other installed applications, for instance, voice management over the phone’s keyboard.

Using this service, we were able to find the required component in the security application: the “Open Door” button with ACTION_CLICK. However, we could not tap it, as the application is designed to be unresponsive to short taps. In order to unlock the doors, one would need to press and hold the button for a few seconds. The pressure on the button is processed by a special algorithm, and of course, there is no API that would allow us to adjust the time of a virtual press in Android. Thus, we were forced to look for other ways of press the button.

…And we found it! The application successfully responded to left and right swipes on the button. We wrote a small program that moved a virtual finger over the button for two seconds, unlocking the security system. After many attempts, we finally did it.

After that, we went for a Bluetooth connection, which also looked promising. The system interacted via Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE), so we had state-of-the-art technology on our hands. However, there was a flipside to the coin, as the hacker community had been working on a means of intercepting BLE data for a couple of years.

With that in mind, we prepared a booth using a laptop with a BLE interface and acquired another USB BLE adapter: we needed two interfaces to successfully implement a man-in-the-middle attack. For the attack, we tried to scan the targeted device, the alarm system, to get the required data and create a copy of that in one of the BLE interfaces of the laptop. Being a BLE system, the alarm transmitted relatively infrequently. This is done in order to optimize battery power usage, which comes in handy when you are the driver. We could thus generate signals from its fake copy more frequently, prompting the phone to connect it instead of the original. If we were successful, one BLE interface of our MITM station would communicate with the security system on behalf of the phone, while the second interface on the laptop would communicate with the original authorized phone. We would thus intercept the traffic and even be able to generate more, for example, to command the system to open the door.

So, we had a working alarm system broadcasting via BLE and paired with the original smartphone, and an MITM station. Now we needed to create a fake copy of the system and force the phone to connect to it. While scanning, our MITM booth was supposed to detect the security system when we set the correct MAC address of the original phone’s Bluetooth interface. And this was when we suffered a complete failure. The system utterly refused to give us the information required for creating a fake copy. We changed MAC addresses and the interface—nothing worked: the system kept connecting only to the phone with which it was originally paired.

As it turned out, the system could be paired with only one particular phone, and the communication channel between the alarm system and phone was encrypted. It also appeared that to establish communication between the phone and the system itself, the user would need to switch the system into programming mode. After that, the system would wait for a connection request form the phone. The pairing procedure was performed in a tricky way: as we said above, it is done via service stations. The control unit was hidden inside the car and accompanied with a unique PIN for activating it. The pairing process itself is further encrypted: the system and the phone exchange encryption keys, establishing a secure communication session, after which the system refuses to communicate with any other phone other than the one originally authorized.

Thus, one cannot simply connect to the system from a random device—that is what we call “built with security in mind”. Therefore, the manufacturer has implemented an excellent product within the second attack vector as well.

Considering all the above, the scenario of a successful attack would be as follows. First, the cybercriminal would need the driver’s phone number. There are multiple ways to get that: for instance, many drivers in Russia leave their cellphone number right behind the windshield for emergency contact. This is followed by the stage of phone infection, for instance via a targeted attack. If successful, the victim’s phone is infected with a Trojan that has the permission to use accessibility services. This would allow to track the victim down and to command applications on their phone to open the car doors. Even though the Bluetooth range is not large, it is theoretically possible for a hacker to discreetly open the door and start the engine while the victim is somewhere near their car.

So, the main result of this research is simple: the biggest security issue here is the smartphone, which can be attacked in numerous ways. One could steal it while unlocked and command it to open the door via the original application that does not require a password. Alternatively, one could build an application that would command the system to open the door or target the original applications that are vulnerable to almost any existing attack scenario, including attacks via Android Accessibility service. One could also infect the phone via SMS or malicious spam, or by posting a trojanized application on Google Play. After that, the trojan can simply hide and wait for the right situation to discreetly unlock the phone, launch the application and command it to open the door. The hacker just needs to be somewhere around the car and the victim’s infected mobile phone. While the Bluetooth range is not large enough for performing all the steps needed for hijacking the car, opened doors seem to be a danger worth paying attention to. However, this security issue is not the alarm system vendor’s responsibility.

What can be done to fix that? Well, first of all, it is not a good idea to manage this type of security systems via a phone. But even if that is the case, it is truly necessary for vendors to implement unlocking patterns for alarm security applications, just like with banking apps. Overall, it is difficult to counteract attacks on Android smartphones, but the hacker’s task can be greatly complicated. For example, for accessibility services, that could be done through obfuscation of application component titles. It is also reasonable to add user authorization by template. None of these measures will stop attackers but will make their lives much harder. As for users, we urge everyone to be cautious when it comes to mobile security. And do not forget about mobile security solutions.

GPS tracker for cars: is the Big Brother watching you?

Another device we checked was a compact GPS tracker for cars with water protection and a magnetic mount. It assumes a wide range of usage scenarios: from controlling employees’ movements in their personal vehicles to tracking the delivery of parcels and cargo, and protection of rental equipment.

The default kit includes a SIM card with a special plan attached to it. However, you can use your own SIM, too. The main thing here is to have GPRS and SMS support. The latter duplicates a GPRS channel for situations when there is no GPRS signal, or to cut roaming costs.

GPS coordinates, accelerometer and other sensor data are transmitted via the GSM/GPRS channel to the provider’s servers. Whilst there is not a lot we can do with the tracker itself, there is plenty of room for malicious activity on the server side of the system. We decided to assess the possibility of a potential attack on the trackers’ web services. The motivation for the hacker here is simple: given access to the corporate account, a malevolent competition agent would be able to track employees’ logistics, account balances or personal data.

Initial analysis has shown that the system utilizes a well-known GPS-monitoring and telematics platform for operation. However, we were unable to identify any vulnerabilities in that.

We then decided to research the service’s official website. We found that it was based on WordPress v4.9.9. There were no publicly reported vulnerabilities linked to that version.

Two website directories have attracted our attention: the administrator sand customer login form. Both could be subjected to a brute-force attack, especially given the fact that the latter does not support two-factor authentication.

Upon successful application of this infection vector to the latter form, the malevolent user could, in theory, access the customer base, which is equivalent to possession of the bulk of private data including, but not limited to, travel patterns, financial data, contacts and names. And in the case of the other form, this would include financial data, transaction history and accounting documents.

Thus, theoretically, and even with limited connectivity, the tracker in question could be successfully exploited due to simple lack of vigilance when securing the web services. However, the possibility of this is so low that there are no real reasons to be worried.

Smart App-Controlled Dashcam: have you put an eye on your car security?

Thanks to modern technology, we can use special dashcams to record what is happening around the car while driving in order to have evidence ready in case of an accident. As with other types of devices, we are seeing more and more “smart” dashcams enter the market, so we decided to analyze one of these to understand which useful features along with potential security risks they have as part of the IoT world.

We selected one of the most popular “smart” dashcams in the market and were initially quite skeptical about the security standard of the device. According to supplied documentation, there were two official applications for both Android and iOS available and a WiFi-interface was used for communication between the device and smartphone or tablet—we had seen plenty of cases when this kind of set up led to disastrous security issues in other IoT-devices.

We will start with initial analysis. The core device functionality includes the following:

- Recording wide-angle (130°) 1080 Full HD video while the car ignition is on, with videos stored on a microSD flash memory card and cyclically overwritten. The size of the stored data depends on the card.

- Recording emergency videos, with potential emergencies detected by a special G-Sensor. These videos are stored in a separate folder for ease of search and safety against overwriting. A more advanced model of this device can record emergency videos while the car is parked and ignition is off.

- Activating night vision mode to adjust the quality of recorded video during nighttime;

- Connecting to an Android or iOS device with a special management application installed;

- Understanding various user voice commands.

We were pleasantly surprised with the security assessment of both the device and official applications that follows. The main point is that the only option for external intruder to gain control over the device, for example, for the purpose of stealing recorded videos, the scenario where the owner’s smartphone is infected aside, is to connect to the camera’s own WiFi hotspot. After connecting, the attacker can either use one of the official applications to retrieve all the data or connect to the camera server on the local network in order to take advantage of the various hidden features not listed in the applications, for example, to brick the device.

The developers have the WiFi connection process covered. If you want to connect a new device to the camera, you need to both enter the password and push a special button on the camera itself. This makes it impossible to connect to the device without physical access, which would make no sense anyway, because with physical access, you can steal the microSD card with all data on it. In addition, it is possible to change the hotspot password in the application, and the user is offered to change the default password upon establishing the first connection.

To sum it up, we can see that device manufacturers and software developers are starting to pay more attention to security issues as they produce various “smart” IoT devices. If this dashcam is used by a thoughtful individual who will consider changing the default password upon the initial connection, all the data will be invulnerable to external intruders.

Conclusions

So, after all that, the last question we have to ask ourselves is: what did we learn? Perhaps we learnt to keep our small-scale testing going. The main outcomes of our experiment with automotive-related smart or connected devices showed that their security status is more or less adequate, as long as minor issues are ignored. This is partly due to the limited device functionality and a lack of serious consequences in case of a successful attack—but also thanks to the vendors’ vigilance.

Yet, seeing how the industry progresses towards a more connected and smartly bright future, this is no reason to rest easy: the golden rule here is that the smarter the object is, the more consideration must be given to its security at the stage of development and patch management. After all, one unpatched vulnerability or carelessness at one particular stage of product development or in use could result in a victim’s car hijacked or a successful attempt at spying on a car fleet.

Keeping that and the upcoming vacation season in mind, we would like to share the following advice on how to choose IoT devices for your smart car:

- When choosing what part of your vehicle you are going to make a little bit smarter, consider the security risks. Think twice if it has something to do with car telemetry or access to its “brain”.

- Before buying a device, search the internet for news of any vulnerability. It is likely that the device you are going to purchase has already been examined by security researchers and it is possible to find out whether the issues found in the device have been patched.

- It is not always a great idea to buy the most recent products released to the market. Along with the standard bugs you get in new products, recently launched devices might contain security issues that have not yet been discovered by security researchers. The best choice is to buy products that have already received several software updates.

- Always consider the security of the “mobile dimension” of the device, especially if you have Android devices—applications are often helpful and make life easier, but once a smartphone is hit by malware, a lot can go wrong.

To overcome challenges of smart device cybersecurity, Kaspersky is investing into Kaspersky OS, widely used in customized manufacturing hardware and software. The system can be used across a variety of fields: on mobile devices and PCs, the Internet of Things, intelligent energy systems, industrial systems, telecommunications, and transportation systems. Kaspersky sees opportunities in the further development of KasperskyOS to meet the needs of our customers and ensure that the highest levels of security can be achieved in all these fields, including automotive industry. More information can be found here.

When it comes to the vendors of IoT devices, the main advice is simple: collaborate with the security vendors and community when developing new devices and improving old ones.

On the IoT road: perks, benefits and security of moving smartly