Having finished episode 1 on a botanical note, let’s continue our trip into the undergrowth by taking a look at the Stuxnet Trojan’s digital signature.

Digitally signed malware is a nightmare for antivirus developers. Digital signatures have a lot riding on them – they act as proof that an application is legitimate, and are a key concept in information security. They also have considerable influence on how effective a security solution is – it’s no secret that a digitally signed file will be “trusted” by security software and will often automatically be allowlisted.

However, sometimes cybercriminals do somehow manage to get their hands on their very own code signing certificate/ signature. Recently, we’ve been seeing regular instances of this with Trojans for mobile phones. When we identify cases like this, we inform the appropriate certification authority, the certificate is revoked, and so on.

However, in the case of Stuxnet, things look very fishy indeed. Because the Trojan isn’t signed with a random digital signature, but the signature of Realtek Semiconductor, one of the biggest producers of computer equipment.

Recalling a certificate from a company like this simply isn’t feasible – it would cause an enormous amount of the software which they’ve released to become unusable.

Getting back to the Trojan itself, let’s look at things in order. Stuxnet creates the following two files: %SystemRoot%system32Drivers: mrxcls.sys, mrxnet.sys

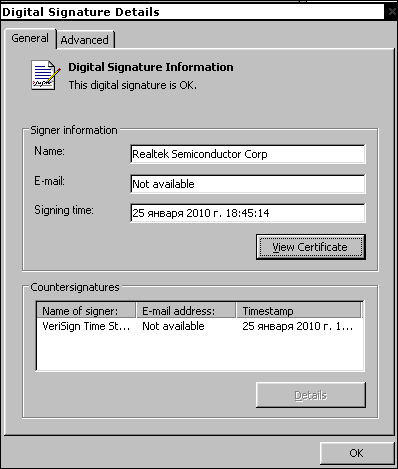

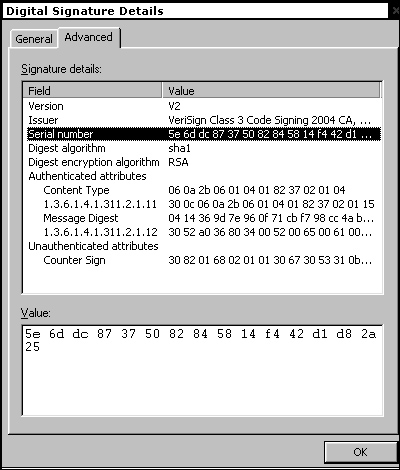

These driver files are designed to support the Trojan’s rootkit functionality – they hide the malware in the system and on infected USB devices. And it’s these files which are digitally signed:

The files were signed on 25 January 2010, meaning that several months elapsed between the files being created, and the middle of June, when the Trojan was first found ITW.

The big question is, how did the cybercriminals manage to sign these files?

Someone in the next office along has just pointed me in the direction of this known “exploit” but this method can’t be used to sign random files.

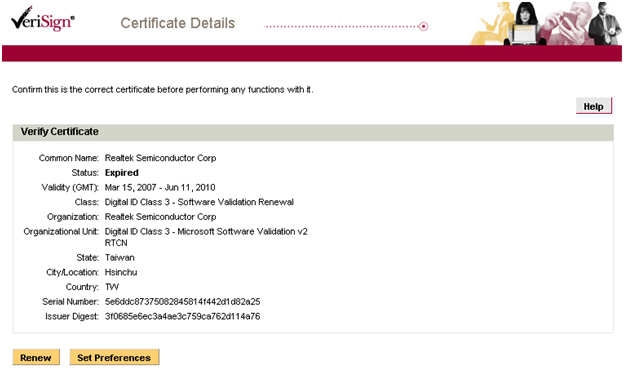

So let’s take a trip over to the Verisign site to check if this certificate actually exists, and if it was actually issued.

As the screenshot shows, the certificate is totally legitimate.

The only fly in the ointment is that the certificate expired on 12 June 2010, a date which pretty much coincides with the date the Trojan was first identified by VBA.

Does this mean the signature made the Trojan “invisible” to antivirus solutions for several months? Maybe.

Everything above points to the following: someone who was able to sign files with the Realtek signature signed the Trojan.

We haven’t got in touch with Realtek about this. We know that VBA contacted them, and still haven’t had an answer. What we can do, though, is use KSN to make sure our products block this digital signature and we’ve already done this.

But is this Trojan actually a threat? Is it widespread? Answers to these questions might help us get to the root of the problem.

To be continued…

Myrtus and Guava, Episode 2