What happened?

At the end of 2021, we were made aware of a UEFI firmware-level compromise through logs from our Firmware Scanner, which has been integrated into Kaspersky products since the beginning of 2019. Further analysis has shown that a single component within the inspected firmware’s image was modified by attackers in a way that allowed them to intercept the original execution flow of the machine’s boot sequence and introduce a sophisticated infection chain.

By examining the components of the rogue firmware and other malicious artefacts from the target’s network, we were able to reach the following conclusions:

- The inspected UEFI firmware was tampered with to embed a malicious code that we dub MoonBounce;

- Due to its emplacement on SPI flash which is located on the motherboard instead of the hard disk, the implant is capable of persisting in the system across disk formatting or replacement;

- The purpose of the implant is to facilitate the deployment of user-mode malware that stages execution of further payloads downloaded from the internet;

- The infection chain itself does not leave any traces on the hard drive, as its components operate in memory only, thus facilitating a fileless attack with a small footprint;

- We detected other non-UEFI implants in the targeted network that communicated with the same infrastructure which hosted the the stager’s payload;

- By assessing the combination of the above findings with network infrastructure fingerprints and other TTPs exhibited by the the attackers; to the best of our knowledge the intrusion set in question can be attributed to APT41, a threat actor that’s been widely reported to be Chinese-speaking;

In this report we describe in detail how the MoonBounce implant works, how it is connected to APT41, and what other traces of activity related to Chinese-speaking actors we were able to observe in the compromised network that could indicate a connection to this threat actor and the underlying campaign.

Revisiting the current state of the art in persistent attacks

In the last year, there have been several public accounts on the ongoing trend of UEFI threats. Notable examples include the UEFI bootkit used as part of the FinSpy surveillance toolset that we reported on, the work of our colleagues from ESET on the ESPectre bootkit, and a little-known threat activity that was discovered within government organisations in the Middle East, using a UEFI bootkit of its own (briefly mentioned in our APT trends report Q3 2021 and covered in more detail in a private APT report delivered to customers of our Threat Intelligence Portal).

The common denominator of those three cases is the fact that the UEFI components targeted for infection reside on the ESP (EFI System Partition), a storage space designated for some UEFI components, typically based in the computer’s hard drive or SSD. The most notable elements of the ESP are the Boot Manager and OS loader, both invoked during the machine’s boot sequence and which also happen to be the subject of tampering in the case of the aforementioned bootkits.

While all of the above were seen in use by advanced actors, a different class of bootkits raises even higher concern. This one is made up of implants found in the UEFI firmware within the SPI flash, a non-volatile storage external to the hard drive. Such bootkits are not only stealthier (partially because of limited visibility by security products into this hardware component), but also more difficult to mitigate: flashing a clean firmware image in place of a malicious one can prove to be more difficult than formatting a hard drive and reinstalling an OS, which would typically eliminate ESP level threats.

MoonBounce is notable for being the third publicly revealed case of an implant from the latter class of firmware-based rootkits. Previous cases included LoJax and MosaicRegressor, which we reported on during October 2020. In that sense, MoonBounce marks a particular evolution in this group of threats by presenting a more complicated attack flow in comparison to its predecessors and a higher level of technical competence by its authors, who demonstrate a thorough understanding of the finer details involved in the UEFI boot process.

Our discovery: a sophisticated implant within UEFI firmware

The UEFI implant, which was detected in spring 2021 , was found to have been incorporated by the attackers into the CORE_DXE component of the firmware (also known as the DXE Foundation), which is called early on at the DXE (Driver Execution Environment) phase of the UEFI boot sequence. Among other things, this component is responsible for initializing essential data structures and function interfaces, one of which is the EFI Boot Services Table – a set of pointers to routines that are part of the CORE_DXE image itself and are callable by other DXE drivers in the boot chain.

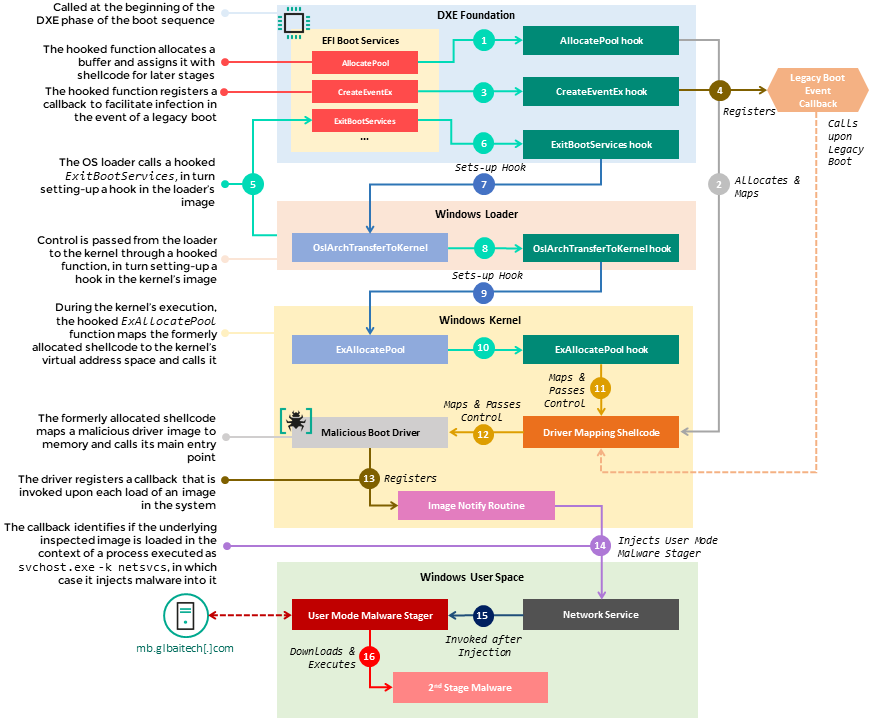

The source of the infection starts with a set of hooks that intercept the execution of several functions in the EFI Boot Services Table, namely AllocatePool, CreateEventEx and ExitBootServices. Those hooks are used to divert the flow of these functions to malicious shellcode that is appended by the attackers to the CORE_DXE image, which in turn sets up additional hooks in subsequent components of the boot chain, namely the Windows loader.

This multistage chain of hooks facilitates the propagation of malicious code from the CORE_DXE image to other boot components during system startup, allowing the introduction of a malicious driver to the memory address space of the Windows kernel. This driver, which runs during the initial phases of the kernel’s execution, is in charge of deploying user-mode malware by injecting it into an svchost.exe process, once the operating system is up and running. Finally, the user mode malware reaches out to a hardcoded C&C URL (i.e. hxxp://mb.glbaitech[.]com/mboard.dll) and attempts to fetch another stage of the payload to run in memory, which we were not able to retrieve.

The diagram below contains the outline of the stages taken from the moment the hooked Boot Services are called in the context of the DXE Foundation’s execution until the user-mode malware is deployed and run during the Operating System’s execution. The full description of each step in the diagram, along with the analysis of both the MoonBounce driver and user-mode malware can be found in the technical document released alongside this report.

Flow of MoonBounce execution from boot sequence to malware deployment in user space

Note that at the time of writing we lack sufficient evidence to retrace how the UEFI firmware was infected in the first place. The infection itself, however, is assumed to have occurred remotely. While previous UEFI firmware compromises (i.e. LoJax and MosaicRegressor) manifested as additions of DXE drivers to the overall firmware image on the SPI flash, the current case exhibits a much more subtle and stealthy technique where an existing firmware component is modified to alter its behaviour. Notably, particular functions were modified with an inline hook, meaning the replacement of the function prologue with an instruction to divert execution to a function chosen by the attacker. This form of binary instrumentation typically requires the attacker to obtain the original image, then parse and change it to introduce malicious logic. This would be possible for an attacker having ongoing and remote access to the targeted machine.

Other pieces of malware on the radar

In addition to MoonBounce, we found infections across multiple nodes in the same network by a known user-mode malware dubbed ScrambleCross, also known as SideWalk. This is an in-memory implant, implemented as position-independent code, that can communicate to a C2 server in order to exchange information and stage the execution of additional plugins in memory, of which none has been sighted in the wild yet. This malware was thoroughly covered by our colleagues at Trend Micro and ESET, so we will refer the reader to their excellent write-ups to understand its internals better.

The position-independent code constituting ScrambleCross can be loaded in one of two ways, the first being a C++ DLL named StealthVector. It obtains the ScrambleCross shellcode by applying a modified ChaCha20 algorithm on an encrypted blob, which may reside as an additional file on disk or be embedded in the loader itself. We detected both variants of this loader in the network in question.

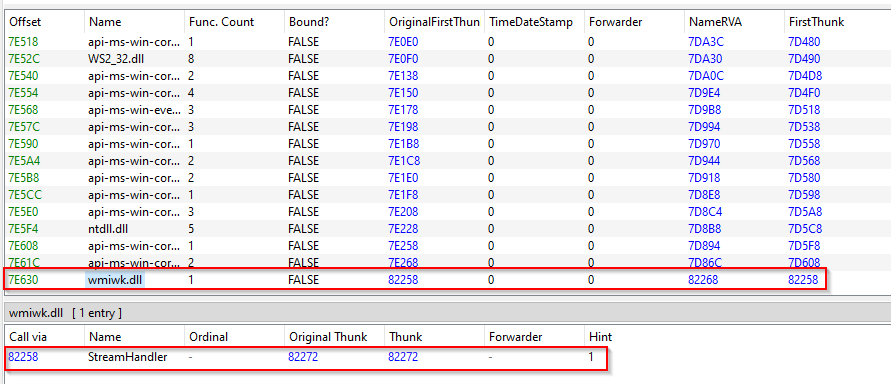

StealthVector gets loaded through the introduction of a modified benign system DLL, in which the import address table is patched to append the malware’s DLL as a dependency. In one case, we observed such altered wbemcomn.dll (MD5: C3B153347AED27435A18E789D8B67E0A) file, which originally facilitates the functionality of WMI in Windows and was located in the directory %SYSTEM%\wbem. As a consequence, when the WMI service was initiated, the rogue version of this DLL forced the loading of a StealthVector image named wmiwk.dll.

Appended IAT entry to a rogue wbemcomn.dll file which forces the loading of StealthVector upon initiation of the WMI service

The table below specifies all instances of StealthVector that we detected in the targeted network, along with timestamp artefacts that might point to the date of their creation.

| Loader Filename | Loader MD5 | Shellcode Filename | C&C Address | Compilation Timestamp |

| wbwkem.dll | 4D5EB9F6F501B4F6EDF981A3C6C4D6FA | compwm.bin | dev.kinopoisksu[.]com | Friday, 12.06.2020 08:25:02 UTC |

| wkbem.dll | E7155C355C90DC113476DDCF765B187D | pcomnl.bin | Unknown | Tuesday, 24.03.2020 09:09:21 UTC |

| wmiwk.dll | 899608DE6B59C63B4AE219C3C13502F5 | wmipl.dll | ns.glbaitech[.]com | Saturday, 20.02.2021 06:45:18 UTC |

| c_20344.nls | 4EF90CEEF2CC9FF3121B34A9891BB28D | – | 217.69.10[.]104 | Tuesday, 24.03.2020 09:09:21 UTC |

| c_20334.nls | CFF2772C44F6F86661AB0A4FFBF86833 | – | st.kinopoisksu[.]com | Tuesday, 24.03.2020 09:09:21 UTC |

Another loader that we detected and is commonly used to load ScrambleCross is .NET based, referred to as StealthMutant. It works by decrypting a shellcode BLOB with AES-256 and injecting it to the address space of another process. The injected process in every case we observed was msdt.exe (Microsoft Diagnostic Troubleshooting Wizard).

StealthMutant is launched in one of two ways, which were partially described in other reports as well. The first way is by executing a launcher utility with the filename System.Mail.Service.dll (MD5: 5F9020983A61446A77AF1976247C443D) through the command line as a service. This is outlined in the following commands typed by the attackers on one of the compromised systems:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

net start "iscsiwmi" sc stop iscsiwmi sc delete iscsiwmi reg add "HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Svchost" /v "iscsiwmi" /t REG_MULTI_SZ /d "iscsiwmi" /f sc create "iscsiwmi" binPath= "$system32\svchost.exe -k iscsiwmi" type= share start= auto error= ignore DisplayName= "iscsiwmi" SC failure "iscsiwmi" reset= 86400 actions= restart/60000/restart/60000/restart/60000 sc description "iscsiwmi" ""iSCSI WMI Classes That Manage Initiators, Ports, Sessions and Connections"" reg add "HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\iscsiwmi\Parameters" /f reg add "HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\iscsiwmi\Parameters" /v "ServiceDll" /t REG_EXPAND_SZ /d "$windir\Microsoft.NET\Framework64\v4.0.30319\System.Mail.Service.dll" /f net start "iscsiwmi" |

The launching utility in turn uses the .NET InstallUtil.exe application in order to execute the StealthMutant image, which has the filename Microsoft.Service.Watch.targets, and providing it with the encrypted ScrambleCross shellcode as an argument from a file named MstUtil.exe.config. The utility itself is a basic C++ program that achieves the aforementioned goal by issuing the following command line using the WinExec API:

|

1 |

C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework64\v4.0.30319\InstallUtil.exe /logfile= /LogToConsole=false /ConfigFile=MstUtil.exe.config /U C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework64\v4.0.30319\Microsoft.Service.Watch.targets |

The second way to execute StealthMutant is through the creation of a scheduled task via a Windows batch script file named schtask.bat, as outlined below:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

@echo off cd /d "%~dp0" copy /Y Microsoft.Service.Watch.targets "C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework64\v4.0.30319\Microsoft.Service.Watch.targets" copy /Y MstUtil.exe.config "C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework64\v4.0.30319\MstUtil.exe.config" schtasks /create /TN "\Microsoft\Windows\UNP\UNPRefreshListTask" /SC ONSTART /TR "C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework64\v4.0.30319\InstallUtil.exe /logfile= /LogToConsole=false /ConfigFile=MstUtil.exe.config /U C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework64\v4.0.30319\Microsoft.Service.Watch.targets" /F /DELAY 0000:02 /RU SYSTEM /RL HIGHEST schtasks /run /TN "\Microsoft\Windows\UNP\UNPRefreshListTask" |

The following table lists known StealthMutant loader IOCs, together with their corresponding ScrambleCross shellcode files and contacted C2 addresses. It’s worth noting that most of the ScrambleCross shellcodes (loaded by both StealthMutant and StealthVector) reached out to the same server (i.e. ns.glbaitech[.]com) and that StealthMutant was observed in this campaign only from February, 2021.

| Loader MD5 | C&C Address | Compilation Timestamp |

| 0603C8AAECBDC523CBD3495E93AFB20C | 92.38.178[.]246 | Tuesday, 23.03.2021 08:00:44 UTC |

| ns.glbaitech[.]com | ||

| 8C7598061D1E8741B8389A80BFD8B8F5 | ns.glbaitech[.]com | Saturday, 20.02.2021 03:27:42 UTC |

| F9F9D6FB3CB94B1CDF9E437141B59E16 | ns.glbaitech[.]com | Wednesday, 08.12.2021 07:07:28 UTC |

In addition to the above components, we found other stagers and post-exploitation malware implants during our research, some of which were attributed to or have been used by known Chinese-speaking threat actors:

- Microcin: a backdoor typically used by the SixLittleMonkeys threat actor, which we have been tracking since 2016. It is worth noting that since its inception, the SixLittleMonkeys group has been using Microcin against various targets, partly against high-profile entities based in Russia and Central Asia.

The implants we observed in this campaign are shipped as DLLs that ought to run in the context of exe, with the primary intent of reading a C2 address from an encrypted configuration file stored in %WINDIR%\debug\netlogon.cfg and reaching out to the server to obtain a further payload. Interestingly, the Trojan holds a scheduling algorithm that would skip any work on Saturdays, checking the local time every hour to determine if Saturday has passed. - Mimikat_ssp: a publicly available post-exploitation tool used to dump credentials and security secrets from exe, also used widely by various Chinese-speaking actors (e.g. GhostEmperor, which we reported on).

- Go implant: a formerly unknown backdoor used to contact a C2 server using a RESTful API, where a combination of a hardcoded IP address and a hypermedia directory path on the underlying server are used for information exchange. Both the IP and the server directory path are encrypted with AES-128 using a base64 encoded key stored in the backdoor’s image. The IP and directory path tuple are used during execution for:

- Initialising communications with the server;

- Sending information from the infected host;

- Requesting a specific server path containing a command for execution and downloading it;

- Sending back the result of the command’s execution to the C2 server.

The commands retrieved from the server are also encrypted with AES-128, with the key stored in the command’s file itself. Command execution results are then encrypted using the same key. We found the following list of supported commands:

- Get list of drives;

- Get content list from a specified directory;

- Download a file from the C2 server;

- Write text to a given *.bat file and execute it;

- Run a shell command.

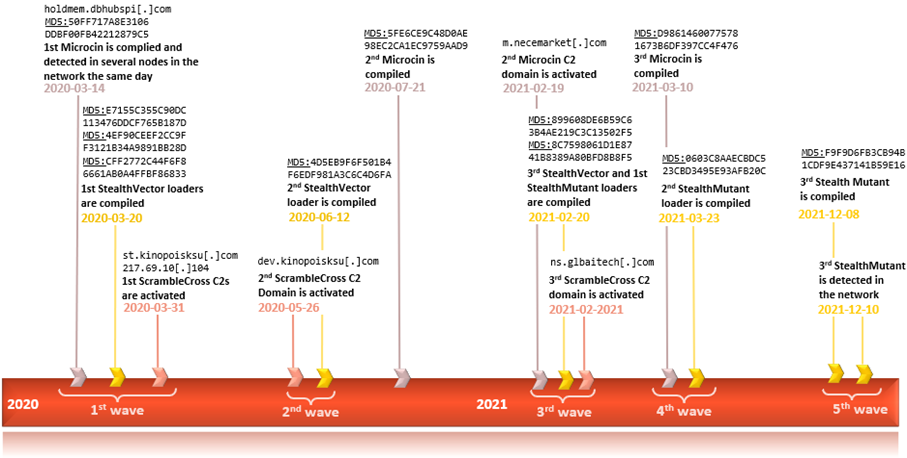

It is important to note that we could not conclusively tie most of those additional pieces of malware to the intrusion set related to MoonBounce, with the exception of Microcin, where some timeline artefacts coincide with other events related to ScrambleCross, as outlined in the figure below. This suggests a low-confidence connection between Microcin and MoonBounce and may indicate usage of shared resources between SixLittleMonkeys and APT41 or involvement of the former’s operators in the MoonBounce activity.

Timeline of events related to artefacts found in the network containing the MoonBounce-infected machine

Who were the targets?

Currently, our detections indicate a very targeted nature of the attack – the presence of the firmware rootkit was detected in a single case. Other affiliated malicious samples (e.g. ScrambleCross and its loaders) were found on multiple other machines in the same network range. In addition, we found several other victims of an undetermined nature with the same versions of ScrambleCross reaching out to the same command and control infrastructure. One particular target corresponds to an organization in control of several enterprises dealing with transport technology.

What were the attackers trying to achieve?

We traced some of the commands executed by the attackers after gaining a foothold in the network, which point to lateral movement and exfiltration of information from particular machines. This aligns in profile with some of the previous operations by APT41, wherein intrusions were typically made to intervene in the targeted companies’ supply chain, or to heist sensitive intellectual property and personally identifiable information. The usage of the UEFI implant in particular indicates the actor’s aim to establish a longstanding foothold within the network, as would be expected in an ongoing espionage activity.

The following are examples of command lines that portray some of the methods and actions taken by the operators of this threat activity to achieve their goals:

- Attempts to enumerate hosts and gather network information:

1234567891011121314cmd /C "C: & cd \ & whoami"cmd /C "C: & cd \ & net view"cmd /C "C: & cd \ & -setcp 866"cmd /C "C: & cd \ & net view"cmd /C "C: & cd \ & netstat -ano"cmd /C "C: & cd \ & dir $temp\ /od"cmd /C "C: & cd \ & arp -a"cmd /C "C: & cd \ & tasklist"cmd /C "C: & cd \ & tracert <redacted_internal_ip>"cmd /C "C: & cd \ & net use \\<redacted_internal_ip> /u:<redacted_username> <redacted_password>"cmd /C "C: & cd \ & net view \\<redacted_internal_ip>"cmd /C "C: & cd \ & ping -n 1 -a <redacted_internal_ip>"cmd /C "C: & cd \ & net use * /d /y"cmd /C "C: & cd \ & systeminfo" - Copying of files across SMB shares, followed by an attempt to dump the Active Directory domain database (tid):

123cmd /C "C: & cd \ & echo ntdsutil \"ac i ntds\" \"ifm\" \"create full $temp\1\\\" q q >$temp\a.batcmd /C "C: & cd \ & type $temp\a.batcmd /C "C: & cd \ & move $temp\a.bat \\<redacted_internal_ip>\c$\windows\temp\\ - Usage of the Sysinternals Psexec tool for remote command execution in the network (as the renamed version tmp):

123$temp\TS_P61S.tmp -accepteula -d -s \\<redacted_internal_ip1>\ cmd /c "arp -a >$temp\TS_P34H.tmp"$temp\TS_P61S.tmp -accepteula -d -s \\<redacted_internal_ip2>\ cmd /c "ping <redacted_internal_ip2> -a -n 2>$temp\TS_P34H.tmp"$temp\TS_P61S.tmp -accepteula -d -s \\<redacted_internal_ip3>\ cmd /c "ping -n 2 -a <redacted_internal_ip2>>$temp\TS_P34H.tmp" - Usage of WMI for remote command execution:

1234567wmic /node:<redacted_internal_ip1> /user:<redacted_group>\<redacted_user> /password:<readcted_password> process call create "cmd /c ping -n 1 -a <redacted_internal_ip4> >$temp\a.tmpwmic /node:<redacted_internal_ip2> /user:<redacted_group>\<redacted_user> /password:<readcted_password> process call create "cmd /c netstat -ano >$temp\a.tmpwmic /node:<redacted_internal_ip2> /user:<redacted_group>\<redacted_user> /password:<readcted_password> process call create "cmd /c tracert <redacted_internal_ip4>>$temp\a.tmpwmic /node:<redacted_internal_ip3> /user:<redacted_group>\<redacted_user> /password:<readcted_password> process call create "cmd /c ipconfig /all >$temp\a.tmpwmic /node:<redacted_internal_ip3> /user:<redacted_group>\<redacted_user> /password:<readcted_password> process call create "cmd /c qwinsta >$temp\a.tmpwmic /node:<redacted_internal_ip3> /user:<redacted_group>\<redacted_user> /password:<readcted_password> process call create "cmd /c net user administrator >$temp\a.tmpwmic /node:<redacted_internal_ip3> /user:<redacted_group>\<redacted_user> /password:<readcted_password> process call create "cmd /c net user admin >$temp\a.tmp - Removal of artefacts from the system:

12345cmd /C "C: & cd \ & dir $temp\ /od"cmd /C "C: & cd \ & dir $temp\*.hive"cmd /C "C: & cd \ & del $temp\*.hive"cmd /C "C: & cd \ & dir $temp\*.log"cmd /C "C: & cd \ & type $temp\silconfig.log" - File archiving of remotely collected files, some of which contain *.hive files, possibly for LSA secrets dumping, with the exe command line utility:

12cmd /C "C: & cd \ & $temp\rar.exe a -r wef.rar \\<redacted_internal_ip1>\c$\windows\temp\1 -hp2wsxcde34rfv7788."c:\windows\temp\rar.exe a -r c:\windows\temp\873.rar \\<redacted_internal_ip2>\c$\windows\temp\*.hive -hp5tgbnhy67ujm3256

Network infrastructure

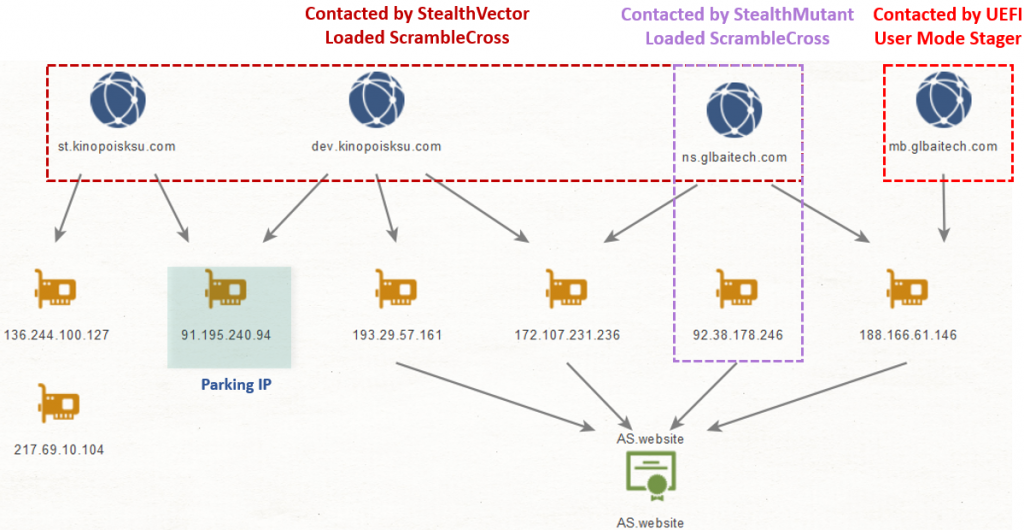

The main cluster of infrastructure serving the activity of the UEFI implant and ScrambleCross implants is outlined in the table below. Note that the attackers maintained the infrastructure from at least March 2020, with some servers seemingly still active at the end of 2021 . During the time the actor switched between multiple hosting providers, resulting in a scattered infrastructure across several ASNs.

| Domain | IP | ASN |

| mb.glbaitech[.]com | 188.166.61[.]146 | AS14061 – DIGITALOCEAN-ASN |

| ns.glbaitech[.]com | 188.166.61[.]146 | AS14061 – DIGITALOCEAN-ASN |

| 172.107.231[.]236 | AS40676 | |

| dev.kinopoisksu[.]com | 172.107.231[.]236 | AS40676 |

| 193.29.57[.]161 | AS48314 – IP-PROJECTS | |

| st.kinopoisksu[.]com | 136.244.100[.]127 | AS20473 – AS-CHOOPA |

| – | 217.69.10[.]104 | AS20473 – AS-CHOOPA |

| – | 92.38.178[.]246 | AS202422 – GHOST |

A careful inspection of the infrastructure shows multiple connections between the servers. It is evident that MoonBounce’s user-mode stager and a few ScrambleCross instances reached out to a single domain, which resolved to the same IP at one point. In addition, there were several overlaps in IPs to which the domains resolved as outlined in the figure below, including one IP that was used to park two domains at different points in time.

Connections between infrastructure elements of MoonBounce and ScrambleCross implants found on the same network

Another important commonality is a unique self-signed SSL certificate, exhibited by multiple servers in this campaign (and only a few dozen others in the wild), which represents a noteworthy fingerprint of the attacker’s network activity.

In addition to the above cluster, we detected two servers related to Microcin’s activity on the same network:

| Domain | IP | ASN |

| m.necemarket[.]com | 172.105.94[.]67 | AS63949 – LINODE |

| holdmem.dbhubspi[.]com | 5.188.93[.]132 | AS202422 – G-Core Labs |

Who is behind the MoonBounce attack?

To the best of our knowledge, the activity described in this report can be attributed to a group widely known as APT41, or an actor closely affiliated to it, with medium to high confidence. In part, our findings align with multiple public accounts from the previous year of either APT41 or other threat actors, namely Earth Baku and SparklingGoblin, which are believed to be alternative names for APT41 or share significant resources and TTPs with it.

Our conclusion, in particular, is done based on the following factors:

- The loading schemes for ScrambleCross, including the usage of StealthVector and StealthMutant in the infection chain, are identical to those observed leveraged by Earth Baku and SparklingGoblin. Apart from the loaders themselves, their launchers seem identical. The attackers used the unique TTP of initiating the loader execution through exe in all cases observed by us. Particularly Install.bat, as used by Earth Baku and described in the public report by Trend Micro mentioned earlier, is highly similar to the sequence of commands used to execute the InstallUtil launcher in our case.

- The ScrambleCross malware itself, which has been reported in use with both Earth Baku and SparklingGoblin, is considered a variant of CROSSWALK, a piece of malware that was described originally by Mandiant as an APT41 tool and remains distinct to the group, to the best of our knowledge.

- A unique certificate retrieved from multiple ScrambleCross C2 servers in the campaign described in this report was sent as a response in a few other dozen servers in the wild, a few of them have been previously reported by the FBI as being part of an APT41-owned infrastructure.

Additionally, the following observations are worth mentioning:

- The user-mode malware stager deployed by the UEFI implant contains a scheduling logic that is somewhat similar to one seen in Microcin samples (some of which were also found on infected hosts in this campaign). This suggests that these groups may be related through shared resources or a prime contractor.

The said scheduling algorithm found in the stager can take a 672-bit bitmask to determine when the malware should start beaconing the C2 server in an attempt to retrieve the payload, whereby the scheduled working time can be decided in a granularity of 15-minute slots (i.e. the stager checks if it is supposed to run in a particular slot out of the 672 possibilities that constitute a full week, or alternatively sleep for 10 seconds before checking if it has reached a dedicated working slot again). A similar scheduling methodology occurs in the case of Microcin, but with a bitmask that simply represents the days of the week on which the malware ought to be active.

Scheduling code used in MoonBounce’s user-mode stager

- The Mimikat_ssp tool found on a few machines in the targeted network has been seen in use by multiple Chinese-speaking threat actors in the past. One recent example is its use in the campaigns of GhostEmperor, as described in a previous report.

- Some elements of shellcode leveraged in MoonBounce were spotted in an old rootkit that was part of a malicious framework dubbed xTalker, which has been seen in the wild since at least 2013, alongside several malware families affiliated to known actors, e.g. NetTraveler, Enfal and Microcin. It was prominently used against Russian-speaking targets including military, governmental entities and think-tanks.

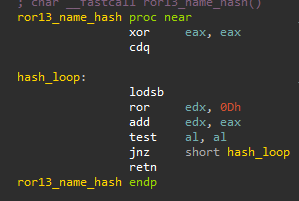

Both components shared a similar name-hashing algorithm, which is outlined below, along with unique corresponding function name hashes (e.g. 0x311B83F, the name hash of ExAllocatePool) that were not seen in use elsewhere in the wild.

Name-hashing algorithm used identically in both MoonBounce and xTalker’s rootkit

In addition, both pieces of code used a technique of replacing magic marker values within shellcode buffers with pointer addresses during runtime. MoonBounce’s code used the marker 0x1122334455667788, while the xTalker rootkit’s code used 0x1234567812345678.

Magic marker values replaced during execution within shellcodes in xTalker’s rootkit and MoonBounce

In the case of xTalker, the above code elements were found within shellcode intended to be staged through an MBR bootkit. However, it is not clear to what extent it was actually used. This may suggest that the MoonBounce and xTalker codes were authored by the same, or a closely affiliated, developer.

Conclusion

In September 2020, the US Department of Justice released a series of indictments against members of the APT41 group, charging them with a high number of computer intrusions against a variety of targets, both in the private and public sectors, some of which included high-profile supply chain attacks. The intrusion set described in this report, and in other public accounts we referred to, shows that the group did not cease to be active despite these legal proceedings.

Moreover, it is evident that the group maintains a high level of proficiency and sophistication in the development of its toolset, gaining a foothold in new areas like UEFI firmware. In this sense, the group has introduced its own innovation to this landscape – patching an existing benign core component in the firmware (rather than adding a new driver to it), thereby turning the UEFI firmware into a highly stealthy and persistent storage for malware in the system.

Following previous predictions, we can now say that UEFI threats are gradually becoming a norm. With this in mind, vendors are taking more precautions to mitigate attacks like MoonBounce, for example by enabling Secure Boot by default. We assess that, in this ongoing arms race, attacks against UEFI will continue to proliferate, with attackers evolving and finding ways to exploit and bypass current security measures.

As a safety measure against this attack and similar ones, it is recommended to update the UEFI firmware regularly and verify that BootGuard, where applicable, is enabled. Likewise, enabling Trust Platform Modules, in case a corresponding hardware is supported on the machine, is also advisable. On top of all, a security product that has visibility into the firmware images should add an extra layer of security, alerting the user on a potential compromise if such occurs.

MoonBounce’ indicators of compromise

EFI Rootkit – Malicious CORE_DXE

D94962550B90DDB3F80F62BD96BD9858

Modified WMI DLL Launcher

C3B153347AED27435A18E789D8B67E0A

StealthVector

4D5EB9F6F501B4F6EDF981A3C6C4D6FA

E7155C355C90DC113476DDCF765B187D

899608DE6B59C63B4AE219C3C13502F5

4EF90CEEF2CC9FF3121B34A9891BB28D

CFF2772C44F6F86661AB0A4FFBF86833

InstallUtil Launcher

5F9020983A61446A77AF1976247C443D

StealthMutant

0603C8AAECBDC523CBD3495E93AFB20C

8C7598061D1E8741B8389A80BFD8B8F5

F9F9D6FB3CB94B1CDF9E437141B59E16

Microcin

5FE6CE9C48D0AE98EC2CA1EC9759AAD9

50FF717A8E3106DDBF00FB42212879C5

D98614600775781673B6DF397CC4F476

Go Implant

C9B250099E2DD27BB4170836AC480FE0

97EF7B8FCDCB0C0D9FBB93D0F7E6E3B6

Mimikat_SSP

4E4388D7967E0433D400C60475974D50

5F1C7602688E67F299F5BD533FA07880

xTalker Rootkit

45E862964EF4EFDEA181F3927D20E96D

4BC82105403974AA24BF02CFB66B8F7C

Domains and IPs

mb.glbaitech[.]com – MoonBounce

ns.glbaitech[.]com – ScrambleCross

dev.kinopoisksu[.]com – ScrambleCross

st.kinopoisksu[.]com – ScrambleCross

188.166.61[.]146 – ScrambleCross

172.107.231[.]236 – ScrambleCross

193.29.57[.]161 – ScrambleCross

136.244.100[.]127 – ScrambleCross

217.69.10[.]104 – ScrambleCross

92.38.178[.]246 – ScrambleCross

m.necemarket[.]com – Microcin

172.105.94[.]67 – Microcin

holdmem.dbhubspi[.]com – Microcin

5.188.93[.]132 – Go malware

5.189.222[.]33 – Go malware

5.183.103[.]122 – Go malware

5.188.108[.]228 – Go malware

45.128.132[.]6 – Go malware

92.223.105[.]246 – Go malware

5.183.101[.]21 – Go malware

5.183.101[.]114 – Go malware

45.128.135[.]15 – Go malware

5.188.108[.]22 – Go malware

70.34.201[.]16 – Go malware

File Names

wbwkem.dll – StealthVector

wkbem.dll – StealthVector

wmiwk.dll – StealthVector

C_20344.nls – StealthVector

C_20334.nls – StealthVector

compwm.bin – ScrambleCross Shellcode

pcomnl.bin – ScrambleCross Shellcode

wmipl.dll – ScrambleCross encrypted shellcode

Microsoft.Service.Watch.targets – StealthMutant

MstUtil.exe.config – ScrambleCross encrypted shellcode

System.Mail.Service.dll – InstallUtil launcher for StealthMutant

schtask.bat – Batch launcher for StealthMutant

CmluaApi.dll – Microcin

ScrambleCross Mutexes

Global\GouZUAkmtdpUmves

Global\PtUojBxCOZGVmQQn

Global\EGuUCpyYIJRTQJAV

Global\YCtiqMgRrpLGbfDo

MoonBounce: the dark side of UEFI firmware

SecurityMonk

Did you verify the effected systems not have BootGuard and/or TPM authentication enabled?

Securelist

The affected system did not support neither BootGuard nor TPM.

Mark Jacobs

How do the attackers “place” it on the SPI flash in the first place? Physical access to the hardware?

Securelist

We don’t have sufficient information as to how writing to the SPI flash happened, however we estimate that it was done through remote access to the machine, not physical access to the hardware.