Overview

Say goodbye to your business: the DigiNotar hack

A simple message on a Google forum in August sparked an investigation which would eventually bring down the DigiNotar certificate authority. The user was concerned that his browser was warning him about a suspect google.com certificate, even though it looked legitimate. His complaint exposed the now notorious DigiNotar hack, which had resulted in 531 rogue certificates being generated by cybercriminals. By using fake SSL certificates for websites, cybercriminals can access data sent to or from those sites even if an encrypted connection is used. The DigiNotar server is believed to have been compromised in early July 2011. The first fake certificate to be detected was issued on 10 July 2011. According to a DigiNotar statement, the company’s employees discovered the hack on 19 July and recalled the rogue certificates. The company considered this response to be sufficient and decided not to go public with the incident. That decision was to have catastrophic consequences: the company failed to identify and recall all the fake certificates and the malicious users behind the hack were able to use them to organize attacks on users. The DigiNotar breach turned out to be much bigger than another similar incident involving the release of fake certificates in the name of the Comodo certificate authority. Among the many resources targeted in the DigiNotar case were government agencies in several countries as well as major Internet services such as Google, Yahoo!, Tor and Mozilla. The 531 fake certificates issued for various websites in the DigiNotar case included those for sites belonging to intelligence agencies in the US (CIA), Israel (Mossad) and the UK (Mi6). It remains unclear what exactly the hackers’ motives were in these particular cases, because sensitive information is obviously not transferred via the official websites of intelligence agencies. One of DigiNotar’s most prominent customers was the Dutch government. The company’s certificates were used by a wide range of agencies and services such as the Netherlands’ national authority for road traffic, transport and vehicle administration (RDW), land registry, tax service etc. After the DigiNotar servers were breached, Dutch governmental bodies were forced to ditch the company’s services and recall their certificates. This meant many systems had to be readjusted to work with new certificates and for some clients this resulted in downtime. This attack demonstrated that systems directly linked to the economy of a country or its government bodies can be compromised or brought to halt by fake certificates. The end for DigiNotar came when the company filed for bankruptcy. As well as having its reputation destroyed, the company had lost all its business. This is not the first time a company has been forced out of business by hacker activity. BlueFrog left the anti-spam business back in 2006 after a massive DDoS attack caused its servers to crash for extended periods of time. The sale of HBGary Federal was cancelled after an attack by Anonymous significantly reduced the value of the company. This year the Australian provider Distribute.IT lost all the data on its servers as a result of a hacker attack. There was nothing left for the company to do but close its business and help the affected websites and mail clients to transfer to other providers. Of course, not all major hacker attacks end so dramatically. Recent incidents involving Sony, RSA and Mitsubishi show that it is possible to stay afloat after an attack. However, it is much easier for big companies to restore their reputations than it is for smaller companies. For a small organization IT security is one of the factors that can determine whether or not it will sink or swim. It should be pointed out that the DigiNotarattack was the second time this year that a certificate authority was hacked. Although the companies that issue root SSL certificates are required to pass a security audit, it is clear that the level of security at DigiNotar and its counterpart Comodo was far from perfect. Just how well protected are the other certificate authorities? Hopefully, the DigiNotar case will serve as a warning for the other market players to strengthen their security policies.

Money for nothing attracts theprostoBitcoin

The possibility of making money out of thin air, especially by using someone else’s computer, was obviously too good an opportunity to miss for cybercriminals. The first malicious programs designed to steal from Bitcoinaccountsor generate money in the system were detected in Q2 2011. They turned out to be rather unsophisticated and were not very widespread. The situation changed in Q3, however. We registered several incidents that suggest the idea of this illegal making-money scheme has caught the imagination of some experienced cybercriminals. In conjunction with Arbor Networks we detected the malicious program Trojan.Win32.Miner.h in August. This particular piece of malware is designed to create P2P botnets. Analysis showed that the network consisted of at least 38,000 computers that are accessible from the Internet. Many of today’s computers work behind routers and other network devices, so the number of machines in the botnet may well be much higher. This extensive botnet is used by cybercriminals to generate bitcoins. Once downloaded to a computer the bot unleashes three programs for generating the virtual currency -Ufasoft miner, RCP miner and Phoenix miner – that connect to bitcoin pools in various countries. The second case of a botnet being used to make money out of Bitcoin was with the much larger TDSS. At the beginning of August TDSS bots started receiving a new configuration file with a miner and Bitcoin pool with the name and password of the beneficiary added in a new section. This was not the cybercriminals’ brightest idea because adding the name and password as well as the Bitcoin pool in the configuration file meant the scam could quickly be closed down. It wasn’t long before a more sophisticated approach was adopted. There is open source software available online for creating your own pool – pushpool. This was used by cybercriminals who configured it to act as a proxy server to a real Bitcoin pool. When connected to this proxy server TDSS bots receive randomly generated user names and passwords for a Bitcoin pool and begin generating money. The real user name and the name of the Bitcoin pool are stored on the proxy server through which all the transactions are made. Unfortunately, this makes it impossible to know who the Bitcoin pool belongs to and how many bitcoins are generated. According to our data, the number of computers infected with TDSS in the first quarter of 2011 stood at 4.5 million. More than a quarter of those machines are located in the US where the latest computer technology is usually used. In other words, the owners of TDSS have at their disposal some very powerful computing resources that are continuing to grow. This type of money-making scheme, however, is subject to the vagaries of an exchange rate. In August, the botnet based on Trojan.Win32.Miner.h also started downloading DDoS bots. It was around this time that the revenue from bitcoins would have fallen due to a significant drop in the exchange rate: in early August a bitcoin was worth $13; by the end of September it was worth $4.8.

Personal data of 35 million South Koreans in the hands of hackers

One of the most serious incidents in the third quarter of 2011 was the theft of personal data belonging to 35 million South Korean users of the social network CyWorld. The full names, postal addresses and telephone numbers of nearly three quarters of the country’s population of 49 million ended up in the hands of cybercriminals. Such a major breach was the result of servers being hacked at SK Telecom, the owner of the search engine Nibu and the CyWorld social networking site. What are the implications of the theft? Well, first of all, the victims could be subjected to spam mailings and phishing attacks. Cybercriminals could use the information to trick people into divulging secrets about the companies they work for. A lot of security systems that are based on personal data, primarily those used by banks, are also under threat. Moreover, sales of the stolen data are proving popular on the black market among more traditional criminals interested in creating fake documents. Over 70% of the country’s population is faced with these threats! The shock news has even prompted changes in government policy. Previously the South Korean government had been trying to curb anonymity on the Internet and users were required to give genuine personal data before publishing anything on popular sites. After such a major leak the government plans to scrap that policy and once again allow anonymity online.

BIOS infection: perfecting the technology of concealment

As the saying goes: “There is nothing new under the sun”. This is particularly appropriate when it comes to the technology of BIOS infections and a new Trojan using that technology: Backdoor.Win32.Mebromi.It is more than 10 years since the emergence of the infamous CIH virus (a.k.a. Chernobyl) that was capable of infecting BIOS. Why have virus writers decided to revisit MBR and BIOS infections? It is primarily down to the use of antivirus technologies. New features in today’s operating systems such as only being able to install drivers from trusted vendors and the ability to check the integrity of those drivers has made it more difficult to install a rootkit on a running system. This means virus writers have had to look for ways of launching their creations before the operating system starts.

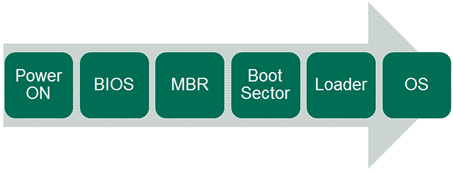

Diagram 1.The standard operating system start-up process

Diagram 1.The standard operating system start-up process

As can be seen in the diagram above, there are several stages where malicious users can try to intervene between the ‘Power On’ button being pressed and the operating system starting. The rise in the number of x64 systems has, as we predicted, led to an increase in the number of bootkits – malware that infects the MBR. However, antivirus vendors have been quick to find effective solutions to this type of infection. Infecting BIOS was the only option left to the cybercriminals.Backdoor.Win32.Mebromi consists of several components: an installer, a rootkit, an MBR dropper with file virus functionality, and a BIOS dropper. We are most interested in the code that is added to BIOS. Its functionality is limited to checking that the MBR is infected and restoring the infection if it isn’t. After that the malware functions like a typical bootkit, despite the fact that, in theory, infected BIOS opens up a whole range of possibilities for malicious code. Looking at the list of components, it is not immediately clear where the main payload is hidden. In fact, all the complex technology is implemented with one aim in mind: to secretly download a file from the Internet and then conceal it. Code added to the system file wininit.exe (2000) or winlogon.exe (XP/2003)by the MBR dropperis responsible for performing the download from the Internet. It is this downloaded file – a Trojan-Clicker – that earns money for the cybercriminals. Why does Mebromi do so little? It looks like this has something to do with the malicious program being made up of different components and being based primarily on a known proof of concept for infecting BIOS infection that dates back to 2007. This also appears to explain why it is mainly AWARD-manufactured BIOS that are being infected. So, can we expect to see the further development of these technologies? Right now it looks unlikely because developing this kind of malware is beset with numerous problems. Most computers do not use AWARD BIOS. Enthusiasts may try to come up with something like Mebromi for other BIOS, but creating universal code for all types of BIOS would not be easy because manufacturers use different sizes and different components. Moreover, the amount of memory set aside for BIOS is minimal and there simply may not be enough space for the malicious code. On the other hand, the newer UEFI format that is gradually replacing BIOS may well be of more interest to virus writers. Protecting against and neutralizing this type of malware is difficult, but not impossible for antivirus solutions. In fact, antivirus programs themselves can write to BIOS and subsequently delete any superfluous data. However, this requires extreme care as the slightest mistake can prevent the computer from starting. After the aforementioned CIH virus, motherboards started appearing with duplicate BIOS chips meaning BIOS could be restored if necessary.

Mobile threats. What will the future bring?

tatistics

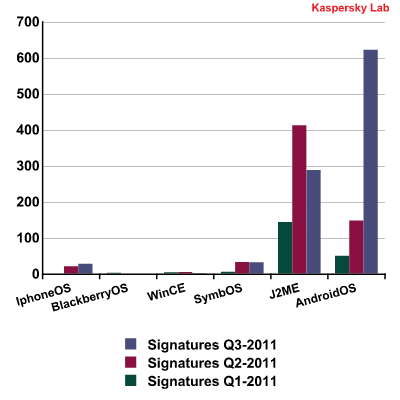

The days are gone when a multitude of vendors and operating systems hampered the development of malware for smartphones. Our statistics show that the cybercriminals have clearly decided to make Android OS the focus of their attacks. Throughout the third quarter we added over 600 signatures for various malicious programs that were designed to work on this platform.

The number of new signatures for mobile threats targeting as election of platforms, Q1, Q2 &Q3 2011

The number of new signatures for mobile threats targeting as election of platforms, Q1, Q2 &Q3 2011

Malware for J2ME came second and primarily targeted China and the post-Soviet states. The share of malware for Symbian is slowly declining – in the first three quarters of 2011 only one new malicious program out of every ten was written for this platform. There were no new programs with a malicious payload detected for the iOS platform, merely exploits that can bypass security systems, allowing other code to be installed and run. However, it looks like the cybercriminals are in no rush to take advantage of these exploits -users still need to be lured to a site where an attack can be launched. Attacks on iOS platforms are generally more complicated and resource-intensive than those on smartphones running Android and other operating systems.

Android malware takes the lead

The proportion of Android malware has dramatically increased in Q3, accounting for 40% of all mobile malware detected in 2011. The analysis of Android malicious programs has revealed that the main driver behind this growth was not the creation of fundamentally new malware but the emergence of large numbers of rather primitive malicious programs that can steal data, send text messages to premium-rate numbers and force-subscribe the user to paid services. These programs were carbon copies of previously known malicious programs created to run under the J2ME platform. There was a mass production of these malicious programs, with the new programs being automatically manufactured on a daily basis, with tried-and-tested J2MEmalware migrating in numbers from legacy devices to those running under Android OS. This migration sees jad-files (J2ME) converted into apk/dex (Android OS). This is a fairly easy task from a technical point of view; moreover, there are online services to help with this operation. In fact, with the help of online converting services malicious users were able to adapt their creations to operate in the new environment at practically no expense. It is important to note that the security system integrated into Android OS could protect users from common Trojans, if only users followed basic security rules. Unfortunately, a moment’s hesitation on the user’s part could allow the Trojan to fulfill all the operations on a displayed list, which can lead to devastating consequences like an empty bank account. However, cybercriminals are going beyond the production of large numbers of malicious programs for Android. We observed in the last report that the evolution of mobile malware is very similar to that of Windows malware. Cybercriminals actively use tried-and-trusted techniques on new platforms. We have detected cases of targeted attacks on Android devices. It is easy to see that a method was used that helps determine the device type and the operating system through the ‘user-agent’ field sent by the browser when a webpage is visited. This procedure is often used in various exploit packs.

Online banking and mobile Trojans

We had anticipated that cybercriminals would look for new ways to make money on Android malware, and it didn’t take long to happen. In July, an Android Trojan of the Zitmo (zeus-in-the-mobile) family was detected that works together with its desktop counterpart Trojan-Spy.Win32.Zeus to allow cybercriminals to bypass the two-factor authentication used in many online banking systems. When two-factor authentication is used, the client must confirm each transaction and system login by sending the code the bank sends to their mobile phone. Without these codes, the cybercriminals cannot steal money from protected user accounts even after gaining access to them with the help of credential-stealing Trojans, like ZeuS and SpyEye. The entire two-factor authentication system is based on the assumption that cybercriminals cannot obtain the codes that banks send to their clients’ mobile phones. However, this is not true if ZeuSand Zitmo work together. ZeuS working in cooperation with Zitmo infects the PC, steals the users’ confidential data and tricks them into installing the mobile Trojan on their mobile phone. When users log in to online banking, they are greeted with a message telling them to install a mobile application, allegedly to be able to use online banking in protected mode. Under the guise of a legal program called Trusteer Rapport, Trojan.AndroidOS.Zitmo finds its ways onto users’ phones. Once entrenched on the user’s mobile phone, Zitmo starts to send copies of all incoming SMSs to a malicious server. The bank’s message with the authentication and login data also follows this path. These are the personal codes that the cybercriminals want. With ZeuS giving login and password data, these SMS codes can be used to complete transactions and transfer money to their own accounts. It should be noted that Zitmo was distributed via Google Market among other channels; it was downloaded less than 50 times from Google Market. This low number suggests that the cybercriminals are now test-running their new technology rather than using it for large-scale scams. There are other methods of bypassing mobile phone authentication for online banking, such as changing the mobile number specified by the client. This is also being test by cybercriminals to identify which methods of bypassing the authentication process are most effective; the results will shape the future evolution of mobile Trojans like Zitmo.

Checkered malware

The last, though by no means least, item in this chapter is the discovery by Kaspersky Lab experts of a partnership program distributing malware via QR codes. A QR code is essentially a barcode that can store more data than regular barcodes. QR codes are commonly used to provide information to mobile devices. All the user has to do is scan the image with the device’s built-in camera and the data contained in the code will appear on the device in an easy-to-read form. Many people use their personal computers to find software to install on their mobile devices. Rather than then entering the software’s URL on the mobile, many sites offer links encoded in QR codes which can be scanned with mobile phones. Cybercriminals used this technique to spread SMS Trojans disguised as Android software by encoding malicious links in QR codes. Upon scanning such QR codes, mobile devices automatically download a malicious APK file (an installation file for Android OS) which, when installed on the device, does what all SMS Trojans do – sends SMS messages to premium-rate numbers. Kaspersky Lab experts have found several websites using QR codes to spread malware. When it comes to cybercriminals taking advantage of the QR code technology, there are a number of possibilities. What we have seen so far is just cybercriminals testing the concept. Substitution of QR codes in advertisements and various posters, both online and offline, clearly poses a much greater threat. Luckily, security solutions developed for mobile devices already provide protection against this threat.

Attacks on the world’s largest corporations

Although corporate security services ought to have tightened up security in the light of some widely-publicized targeted attacks, the number of incidents involving major corporations continues to grow. In Q3 2011, attacks organized by the Anonymous group were reported, as well as attacks conducted by unknown corporate network hackers. The hacktivist group Anonymous was most active in July and August even though several members of the group were arrested. Targets included the Italian cyber police, several police units in the US, and Booz Allen Hamilton, a company that counts the US government among its customers, as well as FBI contractors ManTech International and IRC Federal. Victims of hacktivists also included the rapid transit system serving the San Francisco Bay area (BART), agricultural company Monsanto and defense contractor Vanguard Defense. The attacks resulted in hackers gaining access to these companies’ employee and customer data, internal documentation, correspondence and classified data that members of the group subsequently made available to the general public by posting it on pastebin.com and torrent trackers. In September, Anonymous preferred participation in civil protest action to hacking corporate networks. Apparently, action taken by law enforcement agencies, which have already arrested dozens of malicious users involved in Anonymous attacks, has made those wishing to join the movement to consider the possibility of punishment. Hence, new recruits are choosing less risky forms of protest that are legal in most countries. However, keeping in mind that the group is completely decentralized, it can be safely predicted that its ‘hacker wing’ will continue its attacks. While Anonymous thrives on publicity, other attacks were intended to remain covert, as was the case with the attack on computer systems at Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, a military equipment manufacturer. The attack scenario was virtually identical to that of the intrusion into RSA’s network in March 2011. Employees of the target company received emails with malicious attachments. This time around, it was a PDF file containing an exploit, not an Excel file. Triggering the exploit resulted in a malicious program being loaded on the computer that gave cybercriminals full control of the victim system. After that, all the hackers had to do was find the data they wanted on corporate servers and send it to their own servers. According to the latest available data, computers at several plants manufacturing missiles, submarines and military ships have been infected. Malware was also detected on computers serving the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries headquarters. The hackers were obviously able to access classified documents, but, unlike the RSA incident, it has not been established which information they did access. It is also unclear who conducted the attack. Ordinary cybercriminals, whose top priority is easy profit, are not interested in conducting such attacks.

Geography: domain zones

Registering domain names is a cost incurred by spammers, phishers, distributors of rogue antivirus software and other cyber fraudsters. They try to minimize their financial outlay and prefer compromised domains or domain zones where thousands of domain names can be registered for a few dollars or even free of charge. The latter include the co.cc zone. A number of events took place in Q3 2011 that affected the distribution of malicious content across different domain zones. For instance, Google removed domains registered in the co.cc zone from its search results on 12 June. Note that co.cc domains had been used, among others, by cybercriminals who lured users to malicious pages by tricking search engines, and this measure made malicious users turn to other domain zones. As a result, co.cc fell from 6th place in the malicious domain zone rankings to 15th.Number of blocked web attacks from sites in different domain zones in Q2 and Q3 2011:

| № | Domain zone | Number of blocked attempts to visit a malicious resource in the domain zone | |

| š | Q2 2011 | Q3 2011 | |

| 1 | com | 109075004 | 103275409 |

| 2 | ru | 29584926 | 40253770 |

| 3 | net | 19215209 | 17000212 |

| 4 | info | 11665343 | 8021383 |

| 5 | org | 9267493 | 7833540 |

| 6 | co.cc | 6310221 | 6383968 |

| 7 | in | 5764261 | 3167385 |

| 8 | tv | 3369961 | 2923103 |

| 9 | cz.cc | 3289982 | 2330531 |

| 10 | cc | 2721693 | 1200413 |

Such drastic measures as removing whole domain zones from search results are in fact effective, but so far the effect has been short-lived. There are dozens of domain zones similar to co.cc on the Web, in which registering domain names is either free or very cheap. It is to such domain zones — bz.cm, ae.am,gv.vg — that cybercriminals have moved their malicious websites.

Statistics

Below, we will review some statistics recorded by the various anti-malware modules in Kaspersky Lab products. All of the statistics used in this report have been obtained with the help of consenting participants of the Kaspersky Security Network (KSN). The global exchange of information on malware activities involves millions of Kaspersky Lab product users from 213 countries around the world.

Online threats

The statistical data cited in this section was recorded by the Web Anti-Virus module in Kaspersky Lab products, which is designed to protect users against downloading malicious code from infected web pages. Infected sites include those specifically created by cybercriminals, websites with user-created content such as online forums, and other legitimate websites that have been compromised.

Threats detected on the Internet

In the third quarter or 2011, a total of 22,116,594 attacks launched from Internet resources were blocked all over the world. Of these, 107,413 were recorded as unique modifications of malicious and potentially unwanted programs.Top 20 malicious threats detected on the Internet

| Ranking | Name* | Percentage of all attacks** |

| 1 | Malicious URL | 75.52% |

| 2 | Trojan.Script.Iframer | 2.44% |

| 3 | Trojan.Script.Generic | 1.68% |

| 4 | Exploit.Script.Generic | 1.37% |

| 5 | Trojan.Win32.Generic | 1.04% |

| 6 | AdWare.Win32.Eorezo.heur | 0.75% |

| 7 | Trojan-Downloader.Script.Generic | 0.75% |

| 8 | Trojan.JS.Popupper.aw | 0.55% |

| 9 | AdWare.Win32.Shopper.ee | 0.43% |

| 10 | AdWare.Win32.FunWeb.kd | 0.38% |

| 11 | WebToolbar.Win32.MyWebSearch.gen | 0.33% |

| 12 | Trojan-Downloader.JS.Agent.gay | 0.25% |

| 13 | Trojan.JS.Iframe.tm | 0.23% |

| 14 | Trojan-Downloader.Win32.Generic | 0.22% |

| 15 | AdWare.Win32.FunWeb.jp | 0.21% |

| 16 | Trojan.HTML.Iframe.dl | 0.2% |

| 17 | Trojan.JS.Iframe.ry | 0.18% |

| 18 | Trojan.VBS.StartPage.hl | 0.17% |

| 19 | AdWare.Win32.Shopper.ds | 0.15% |

| 20 | Trojan-Downloader.JS.Agent.fzn | 0.15% |

* Detected verdicts returned by the Web Anti-Virus module. This data is provided by users of Kaspersky Lab products who have consented to share their local statistical data.** Percentage of all web attacks detected on computers of unique users.

Top spot went to a variety of malicious URLs (previously we’d detected them as ‘Blocked’) which are on the Kaspersky Lab denylist. Their overall share of web attacks rose by 15 percentage points, and amounted to three-quarters of all threats blocked during Internet activity. A quarter of the Top 20 is made up of adware – advertising programs which do everything possible to get themselves onto users’ computers. These programs are designed with one simple objective: after being installed on a computer – generally in the guise of a browser add-on – they display advertising messages to the user. Eleven threats in the Q3 Top 20 exploit software vulnerabilities and are used to deliver malicious programs to user computers. Over 75% of all blocked online threats are malicious URLs (webpages infected with exploit packs, bots, ransomware Trojans, etc.). There are two ways that users could risk running into infected websites. First, they stealthily redirect users from other sites, including legitimate websites that have been hacked using drive-by attack scripts. Second, users often click on dangerous links themselves. Cybercriminals put these links in emails and on social networking sites, publish them on questionable or hacked websites, or plant them into search engines using Blackhat SEO methods. We have put together ratings to show which web resources have most frequently attempted to redirect KSN users to malicious sites in Q3 2011. The malicious links were subsequently blocked by Kaspersky Lab products.Top 3 Internet resources with redirects to malicious links in Q3 2011

| Site name | Site type | Average number of redirect attempts per day |

| The largest social network | 96 000 | |

| The world’s largest search engine | 30 000 | |

| Yandex | The largest search engine on the Russian-language Internet | 24 000 |

The number one source of ‘voluntary’ redirects to dangerous websites is Facebook. User computers running KSN block nearly 100,000 redirect attempts every day from this social network. Virus writers use all sorts of social engineering ploys to trick users into clicking on their links. Cybercriminals particularly love to use hot topics to lure users into their trap. This quarter, the most popular offers were scandalous photos of Hollywood stars and the alleged chance of winning a free iPhone 5.Second and third places were taken by Google and Yandex, respectively. Unfortunately, search engines can also pose a threat. Malicious users actively apply Blackhat SEO tactics to trick search engines into placing malicious links among the first responses to a query. Another possible reason for search engines’ high ranking in this category is users being led to a popular website which has been hacked.

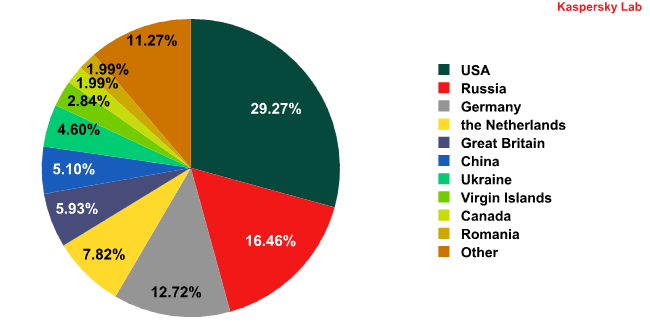

Malware-hosting countries

The geographical location of each attack source was determined by comparing the domain name to the actual IP address of the domain and identifying the geographical location of the IP address (GEOIP).As it turns out, 88% of online resources used to spread malicious programs in the third quarter of 2011 came from just 10 countries.  The distribution of countries with malware-hosting web resources in Q3 2011, by country.The Top 10 malware-hosting countries in Q3 2011 feature just one change from last quarter: Romania rose up to 10th place, pushing Sweden (1.3%) down two spots. The top three countries are unchanged, although some of the Top 10 have swapped places. Over the past three months, the percentage of hosting services located in Germany (+4.9 percentage points) and the Virgin Islands (+2.8 percentage points) surged, while the share of hosting services with malicious programs dwindled in the UK (-1.7 percentage points), Canada (-1.5 percentage points) and Ukraine (-1.2 percentage points).

The distribution of countries with malware-hosting web resources in Q3 2011, by country.The Top 10 malware-hosting countries in Q3 2011 feature just one change from last quarter: Romania rose up to 10th place, pushing Sweden (1.3%) down two spots. The top three countries are unchanged, although some of the Top 10 have swapped places. Over the past three months, the percentage of hosting services located in Germany (+4.9 percentage points) and the Virgin Islands (+2.8 percentage points) surged, while the share of hosting services with malicious programs dwindled in the UK (-1.7 percentage points), Canada (-1.5 percentage points) and Ukraine (-1.2 percentage points).

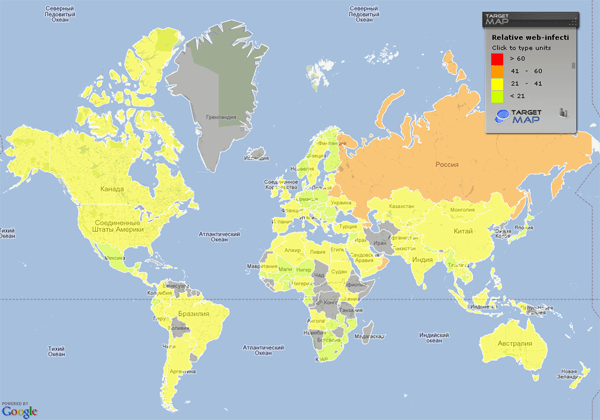

High-risk countries

In order to assess the risk level for online infection in different countries, we calculated the frequency of detections recorded on user computers in each country.The Top 10 high-risk countries

| Ranking | Country* | Percentage of unique users** |

| 1 | Russian Federation | 50.0% |

| 2 | Oman | 47.5% |

| 3 | Armenia | 45.4% |

| 4 | Belarus | 42.3% |

| 5 | Azerbaijan | 41.1% |

| 6 | Kazakhstan | 40.9% |

| 7 | Iraq | 40.3% |

| 8 | Tajikistan | 39.1% |

| 9 | Ukraine | 39.1% |

| 10 | Sudan | 38.1% |

*Countries with fewer than 10,000 users of Kaspersky Lab products were not included in these calculations.**The number of individual user computers that were attacked via the web as a percentage of the total number of users of Kaspersky Lab products in the country.

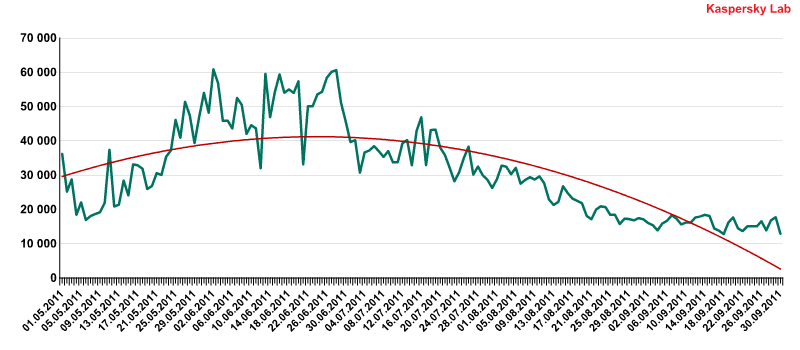

This quarter, the US (32%), Saudi Arabia (30.9%) and Kuwait (28.8%) all left the Top 10. They were replaced by Tajikistan and Kazakhstan, where the number of Internet users is growing fast, as well as Ukraine. The share of user computers attacked in the US fell by 8 percentage points, due to a considerable decrease in the prevalence of fake antivirus programs. The number of these fraudulent programs skyrocketed last quarter, but then fell back to its usual range in August. This also affected other developed countries where the percentage of computers targeted in online attacks also fell, such as the UK (24.7%, down by 10 percentage points) and Canada (24.6%, down by 8 percentage points).  The number of fake antivirus attacks per day, May-September 2011All of these countries can be divided into several groups (note that this quarter, two new countries made our Top 10: Libya (24.7%) and Nigeria (15%).

The number of fake antivirus attacks per day, May-September 2011All of these countries can be divided into several groups (note that this quarter, two new countries made our Top 10: Libya (24.7%) and Nigeria (15%).

- High-risk countries. This group features risk levels ranging from 41% to 60% and includes 5 countries this quarter: Russia (50%), Oman (47.5%), Armenia (45.5%), Belarus (42.3%), and Azerbaijan (41.1%).

- Average-risk countries. This group includes countries with risk levels ranging from 21% up to 41%, and in the third quarter this year included 79 countries, including China (37.9%), the US (32%), Brazil (28.4%), Spain (22.4%), and France (22.1%).

- Safe surfing countries. This past quarter, this group comprised 48 countries with risk levels ranging from 10% up to 21%.

The distribution among these groups has changed considerably since last quarter. Iraq (-1.1 percentage points), Sudan (-5.3percentage points) and Saudi Arabia (-11.7percentage points) all dropped from the high-risk category down to average-risk. The safe surfing category includes an extra 19 countries that had been in the average-risk group last quarter. With the addition of Nigeria, a country new to our rankings, the number of safe surfing countries has increased by 20.The countries with the smallest percentages of users subjected to online attacks were Denmark (10.9%), Japan (12.8%), Slovenia (13.2%), Luxembourg (14.5%), Taiwan (14.7%), Slovakia (16%) and Switzerland (16.4%).  The risk of online infection in different countriesOn average, 24.4% of computers of all KSN users — practically one in four computers around the world — have been targeted in an online attack at least once.The average amount of targeted computers fell 3 percentage points compared to last quarter. Meanwhile, the number of online attacks increased by 8%, from 208,707,447 in Q2 to 226,116,594 in Q3. This means that the sources of the attacks are becoming more dangerous: each malicious webpage on a user computer attempts to penetrate the system with several malicious programs at once.The on-going joint efforts of law enforcement agencies working with antivirus companies have been productive. First and foremost, they are working on reducing the number of infected computers. Furthermore, modern operating systems are become more secure and users are increasingly moving to newer systems, so malicious users are now attempting to infect computers with several malicious programs at once.

The risk of online infection in different countriesOn average, 24.4% of computers of all KSN users — practically one in four computers around the world — have been targeted in an online attack at least once.The average amount of targeted computers fell 3 percentage points compared to last quarter. Meanwhile, the number of online attacks increased by 8%, from 208,707,447 in Q2 to 226,116,594 in Q3. This means that the sources of the attacks are becoming more dangerous: each malicious webpage on a user computer attempts to penetrate the system with several malicious programs at once.The on-going joint efforts of law enforcement agencies working with antivirus companies have been productive. First and foremost, they are working on reducing the number of infected computers. Furthermore, modern operating systems are become more secure and users are increasingly moving to newer systems, so malicious users are now attempting to infect computers with several malicious programs at once.

Local threats

In this section of our quarterly reports we have revised the methodology. Now we have added data from the scanning of different disks, including on-demand scanners, to the statistics from the on-access scanner.

Threats detected on user computers

In the third quarter of this year, Kaspersky Lab solutions successfully blocked 600,344,563 attempted local infections on user computers within the framework of KSN.During these attempts, user on-access scanners recorded 429,685 unique modifications of malicious and potentially unwanted programs.The Top 20 threats detected on user computers

| Rank | Name | % of individual users* |

| 1 | Trojan.Win32.Generic | 17.7% |

| 2 | DangerousObject.Multi.Generic | 17.4% |

| 3 | Net-Worm.Win32.Kido.ih | 6.9% |

| 4 | Trojan.Win32.Starter.yy | 5.8% |

| 5 | Virus.Win32.Sality.aa | 5.5% |

| 6 | Net-Worm.Win32.Kido.ir | 5.3% |

| 7 | Virus.Win32.Sality.bh | 4.7% |

| 8 | Virus.Win32.Sality.ag | 3.0% |

| 9 | HiddenObject.Multi.Generic | 2.5% |

| 10 | Virus.Win32.Nimnul.a | 2.4% |

| 11 | Worm.Win32.Generic | 2.2% |

| 12 | Hoax.Win32.ArchSMS.heur | 2.2% |

| 13 | Exploit.Java.CVE-2010-4452.a | 1.7% |

| 14 | AdWare.Win32.FunWeb.kd | 1.7% |

| 15 | Packed.Win32.Katusha.o | 1.7% |

| 16 | Virus.Win32.Generic | 1.6% |

| 17 | Packed.Win32.Krap.ar | 1.6% |

| 18 | Backdoor.Win32.Spammy.gf | 1.6% |

| 19 | Trojan-Downloader.Win32.FlyStudio.kx | 1.6% |

| 20 | Worm.Win32.VBNA.b | 1.6% |

* These statistics are compiled from the malware detection verdicts generated by the antivirus modules of users of Kaspersky Lab products who have agreed to submit their statistical data.** The number of individual users on whose computers the antivirus module detected these objects as a percentage of all individual users of Kaspersky Lab products on whose computers a malicious program was detected.Top place in the ranking was taken by Trojan.Win32.Generic (17.7%), uncovered by the heuristic analyzer in a proactive detection process for numerous malicious programs. The assortment of malware that makes up the second place entry was detected using cloud technologies. These technologies reinforce antivirus databases: when there is no signature or heuristic data to detect a specific piece of malware, an antivirus company’s cloud resources may already have data about the threat. In this case, the threat was DangerousObject.Multi.Generic (17.4%).Half of the rankings this quarter are made up of self-replicating programs, i.e. viruses and worms that infect removable media and/or executable files. A number of auxiliary applications – such as utility files which launch the main threats – feature in the Top 20 this quarter. These include, for example, Trojan.Win32.Starteryy, which appears on a computer after operations are executed by Virus.Win32.Nimnul to launch Backdoor.Win32.IRCNite.clf and Worm.Win32.Agent.adz.Packed.Win32.Krap.ar, Packed.Win32.Katusha.o and Worm.Win32.VBNA.b are all essentially ‘launch pads’ for other malicious programs. They are primarily used by malicious users to prevent detection of the delivery process for fake antivirus programs.

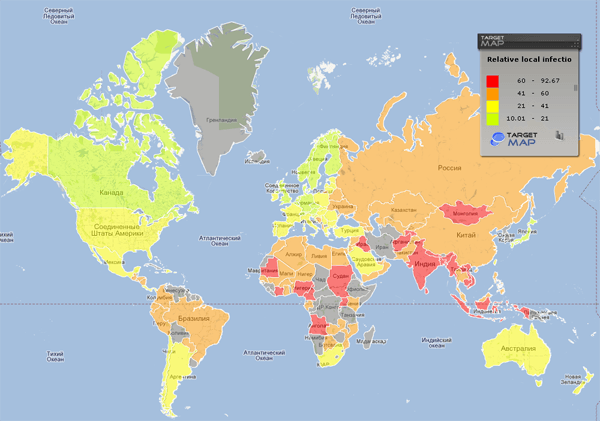

Countries with the highest risk of local infection

We have extrapolated the percentage of infected computers in countries where KSN has more than 10,000 users by calculating how many computers blocked local attempts to infect them.Top 10 countries in terms of infected computers

| Rank | Country* | % of individual users |

| 1 | bangladesh | 92.7 |

| 2 | sudan | 87.5 |

| 3 | rwanda | 74.8 |

| 4 | tanzania, united republic of | 73.4 |

| 5 | angola | 72.5 |

| 6 | nepal | 72.2 |

| 7 | iraq | 72.0 |

| 8 | india | 70.9 |

| 9 | uganda | 69.8 |

| 10 | afghanistan | 68.0 |

* Countries with fewer than 10,000 users of Kaspersky Lab products were not included in the calculations** The number of individual users on whose computers local threats were blocked as a percentage of all Kaspersky Lab product users in the country.The changes in our calculation methods produced only one change in our rankings: Uganda replaced Mongolia. Now the figures account for all malicious programs, whether in the computer’s hard drive or on removable media. The clear leader is Bangladesh (92.7%), where our products detected and blocked malicious programs on nine out of every 10 computers. Incidentally, the adjustments we made to our methods had a greater impact on the indicators for developing countries. In developed countries, the percentage of computers on which local threats were blocked experienced only minor changes. The increased numbers of targeted computers in developing countries is primarily related to the large numbers of autorun-worms in these areas. Virus writers are keen on spreading their malicious programs via these worms. However, in developed countries, cybercriminals prefer different methods, such as drive-by attacks, to infect computers. We have divided the affected countries into different local infection levels:

- Maximum level of local infection. This group is for countries with infection levels over 60% and includes countries in Asia (Nepal, India, Vietnam, Mongolia, etc.) and Africa (Sudan, Angola, Nigeria, and Cameroon).

- High level of local infection. This group has infection levels ranging from 41% up to 60% and currently includes 55 countries across the globe, such as Egypt, Kazakhstan, Russia, Ecuador, and Brazil.

- Medium level of infection. This group currently includes 37 countries with local infection levels ranging from 21% up to 41%, including Turkey, Mexico, Israel, Latvia, Portugal, Italy, the US, Australia, and France.

- Lowest level of infection: This group has just 16 countries, 14 of which are in Europe (including the UK, Norway, Finland, and the Netherlands) and two from Asia – Japan and Hong Kong.

The risk of local infection around the worldThe five countries with the lowest rates of local infection are:

The risk of local infection around the worldThe five countries with the lowest rates of local infection are:

| Rank | Country | % ofuniqueusers |

| 1 | Japan | 10% |

| 2 | Denmark (+1) | 10.7% |

| 3 | Switzerland (+2) | 14.4% |

| 4 | Germany (-2) | 15.4% |

| 5 | Sweden (+2) | 15.8% |

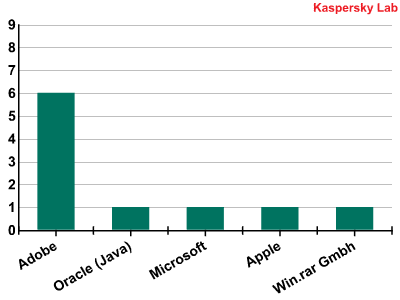

Vulnerabilities

In the third quarter of 2011 a total of 28,060,517 vulnerable programs and files were detected on user computers – an average of 12 different vulnerabilities on each affected computer. The Top 10 are listed in the table below.

| № | Secunia ID – Unique vulnerability number | Vulnerability name and link to description | What the vulnerability lets malicious users do | Percentage of users on whose computers the vulnerability was detected | Date published | Rating |

| 1 | SA 44784 | Sun Java JDK / JRE / SDK Multiple Vulnerabilities | gain access to a system and execute arbitrary code with local user privileges Exposure of sensitive information Manipulation of Data DoS (Denial of Service) | 35.85% | 08.06.2011 | Highly Critical |

| 2 | SA 41340 | Adobe Reader / Acrobat SING “uniqueName” Buffer Overflow Vulnerability | gain access to a system and execute arbitrary code with local user privileges | 28.98% | 08.09.2010 | Extremely Critical |

| 3 | SA 45583 | Adobe Flash Player Multiple Vulnerabilities | gain access to a system and execute arbitrary code with local user privileges exposure of sensitive information | 26.83% | 10.08.2011 | Highly Critical |

| 4 | SA 44964 | Adobe Flash Player Unspecified Memory Corruption Vulnerability | gain access to a system and execute arbitrary code with local user privileges | 20.91% | 15.06.2011 | Extremely Critical |

| 5 | SA 41917 | Adobe Flash Player Multiple Vulnerabilities | gain access to a system and execute arbitrary code with local user privileges exposure of sensitive information bypass security system | 15.24% | 28.10.2010 | Extremely Critical |

| 6 | SA 23655 | Microsoft XML Core Services Multiple Vulnerabilities | gain access to a system and execute arbitrary code with local user privileges DoS (Denial of Service) XSS | 14.99% | 13.07.2011 | Highly Critical |

| 7 | SA 45516 | Apple QuickTime Multiple Vulnerabilities | gain access to a system and execute arbitrary code with local user privileges | 14.93% | 04.08.2011 | Highly Critical |

| 8 | SA 45584 | Adobe Shockwave Player Multiple Vulnerabilities | gain access to a system and execute arbitrary code with local user privileges | 11,00% | 10.08.2011 | Highly Critical |

| 9 | SA 46113 | Adobe Flash Player Multiple Vulnerabilities | gain access to a system and execute arbitrary code with local user privileges XSS bypass security system | 9.67% | 22.09.2011 | Highly Critical |

| 10 | SA 29407 | WinRAR Multiple Unspecified Vulnerabilities | gain access to a system and execute arbitrary code with local user privileges DoS (Denial of Service) | 9.56% | 03.09.2009 | Highly Critical |

*** Percentage of all user computers where at least one vulnerability was detected

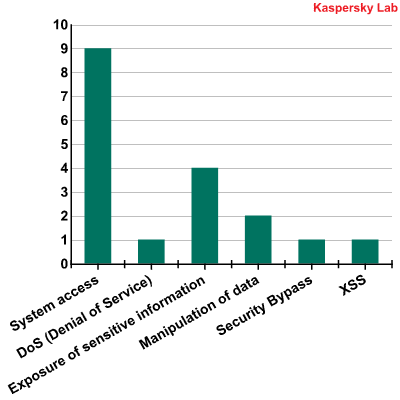

Unlike last quarter, products from five different companies are listed in the ratings, rather than just two. But more than half of the vulnerabilities in our rankings are in Adobe products: Flash Player, Acrobat Reader, and Shockwave Player. Two new vulnerabilities were detected in Apple Quicktime and Microsoft XML Core Services, which explains their return to the Top 10. A relatively old vulnerability from 2009 in the WinRAR packer also made a comeback this quarter.  Manufacturers of products with the Top 10 vulnerabilitiesWe can see that each vulnerability allows malicious users to gain full control over a system. Three vulnerabilities also allow malicious users to launch DoS attacks against a machine running the vulnerable application. Additionally, two vulnerabilities allow malicious users to bypass the security system, two give access to critical system information, two are capable of launching XSS attacks and one is able to manipulate data.

Manufacturers of products with the Top 10 vulnerabilitiesWe can see that each vulnerability allows malicious users to gain full control over a system. Three vulnerabilities also allow malicious users to launch DoS attacks against a machine running the vulnerable application. Additionally, two vulnerabilities allow malicious users to bypass the security system, two give access to critical system information, two are capable of launching XSS attacks and one is able to manipulate data.  Distribution of Top 10 vulnerabilities by type of system impact

Distribution of Top 10 vulnerabilities by type of system impact

Conclusion

Among the new tactics, one worthy of mention is the emergence of malicious code that infects a computer’s BIOS. This type of infection allows malicious code to execute immediately after the power button is pressed — and most importantly, even before the operating system and security program boot up. Ultimately, this technology lets malicious code effectively conceal its presence on the system. Nevertheless, this type of technology is not likely to find favor among malicious users. First of all, creating universal code that can infect all BIOS versions is not a simple task, and second, modern motherboards will use EFI, a new specification that is very different from BIOS. It turns out that all the effort put into developing BIOS infection technology may not have been worth it after all. Essentially, we are watching the evolution of rootkit technologies, and with every step of this evolutionary process, malicious code is targeting earlier and earlier levels of the OS boot process. It is safe to assume that the next step will be the infection of virtual machine managers. This would, however, pose more of a threat to corporate users than home users, since large corporate networks are active users of virtualization technology. Due to heightened interest in major corporations among malicious users, we can expect to see more aggressive use of this concept in the near future. Targeted attacks have become a more or less traditional part of our reports. It should be noted that in the third quarter of 2011, hackers set their sights on Japanese and American companies working on defense contracts. These cyber-operations aim to steal secret documents using more cost-efficient ways to obtain this type of information. Thus, the number of attempts to hack into the systems of companies that work with classified data will continue to rise. Kaspersky Lab has also observed an active migration of mobile malware from the J2ME platform to Android OS. For a long time the fragmentation of the mobile OS market has held back the development of malicious programs targeting mobile devices, but we can now say with certainty that malicious users have made their choice and are now focusing their efforts on writing malware for Android. What types of programs are they? Right now, the most lucrative are fee-based text messages and subscriptions to paid services. During this past quarter, we saw the emergence of an Android Trojan that was primarily designed to steal authorization codes for banking transactions. But these Trojans are capable of more than that. Today’s mobile devices are a means of communication and access to hundreds of different Internet services. We expect to see new malicious programs used to access the accounts of these services and steal data. The schemes used to generate money using malicious programs in the second quarter of this year included the emergence of Trojans targeting the Bitcoin system. In the third quarter, the concept was taken over by large botnets, and thousands of infected machines were set up with crypto-currency generators that used the computer’s resources to create money for malicious users. But the Bitcoin system depends on user trust, and trust affects the value of this crypto-currency, which means that a loss of trust could be a deal breaker for the entire system. Incidents involving Bitcoin system security and the appearance of money-generating botnets have had a negative impact on the system’s reputation, devaluing the virtual currency. Its value has subsequently more than halved, from $13 to $4.80.In the third quarter, Kaspersky Lab expert studies showed that Facebook, the planet’s largest social network, is a hotspot for redirects to malicious links. According to KSN data, each day there are nearly 100,000 malicious redirect attempts via Facebook. Malicious users are taking advantage of the trusting relations that develop on social networks, but for malevolent purposes. According to KSN data from Q3 2011, the number of malicious hosting services on the Internet fell by 12%. At the same time there was an 8% rise in attacks launched against computers connected to the Internet, which suggests that each individual source of malware poses an increased threat. However, the decrease in the number of malicious hosting services is only temporary, and we will see malicious users regain this lost ground in the near future. In light of the upcoming festive season – a busy time for all kinds of cyber scammers – we can say with certainty that the number of sources of malicious programs will increase.

IT Threat Evolution: Q3 2011