There can never be too many IoT gadgets – that’s what people usually think when buying yet another connected device with advanced functionality. From our perspective, we also think there can’t be too many IoT investigations. So, we have continued our experiments into checking and uncovering how vulnerable they are, and followed up our research focusing on smart home devices.

Researchers have already been analyzing connected devices for many years, but concerns around cybersecurity in the IoT world are still there, putting users under significant risk. In our previous analysis, possible attack vectors affecting both a device and a network to which it’s connected have been discovered. This time, we’ve chosen a smart hub designed to control sensors and devices installed at home. It can be used for different purposes, such as energy and water management, monitoring and even security systems.

This tiny box receives information from all the devices connected to it, and if something happens or goes wrong, it immediately notifies its user via phone, SMS or email in accordance with its preferences. An interesting thing is that it is also possible to connect the hub to local emergency services, thus alerts will be sent to them accordingly. So, what if someone was able to interrupt this smart home’s system and gain control over home controllers? It could turn life into a nightmare not only for its user, but also for the emergency services. We decided to check a hypothesis and as a result discovered logical vulnerabilities providing cybercriminals with several attack vectors opportunities.

Physical access

First, we decided to check what could be available for exploitation by an attacker being outside of the network. We discovered that the hub’s firmware is available publicly and can be downloaded without any subscription from the vendor’s servers. Therefore, once downloading it, anyone can easily revise the files inside it and analyze them.

We found that the password from the root account in the shadow file is encrypted with the Data Encryption Standard (DES) algorithm. As practice shows, this cryptographic algorithm is not considered to be secure or highly resistant to hacking, and therefore it is possible for an attacker to successfully obtain the hash through brute-force and find out the ‘root’ password.

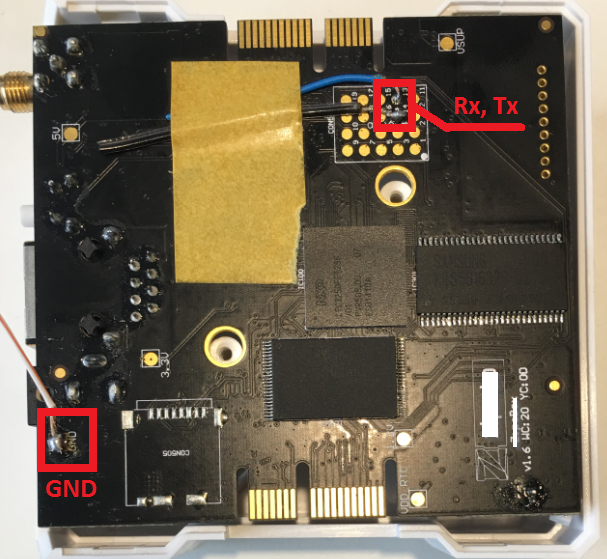

To access the hub with ‘root’ rights and therefore modify files or execute different commands, physical access is needed. However, we don’t neglect the hardware hacking of devices and not all of them survive afterwards.

We explored the device physically, but of course not everyone would be able to do this. However, our further analysis showed there are other options to gain remote access over it.

Remote access

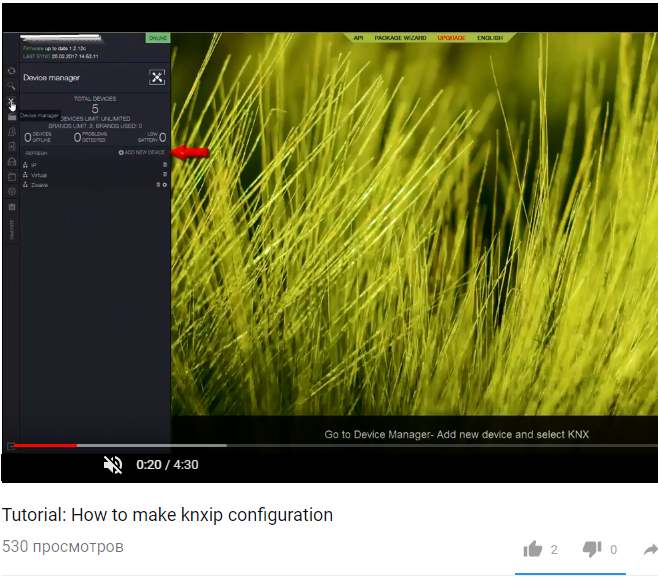

For hub control, users can either use a special mobile application or a web-portal through which they can set up a personal configuration and check all the connected systems.

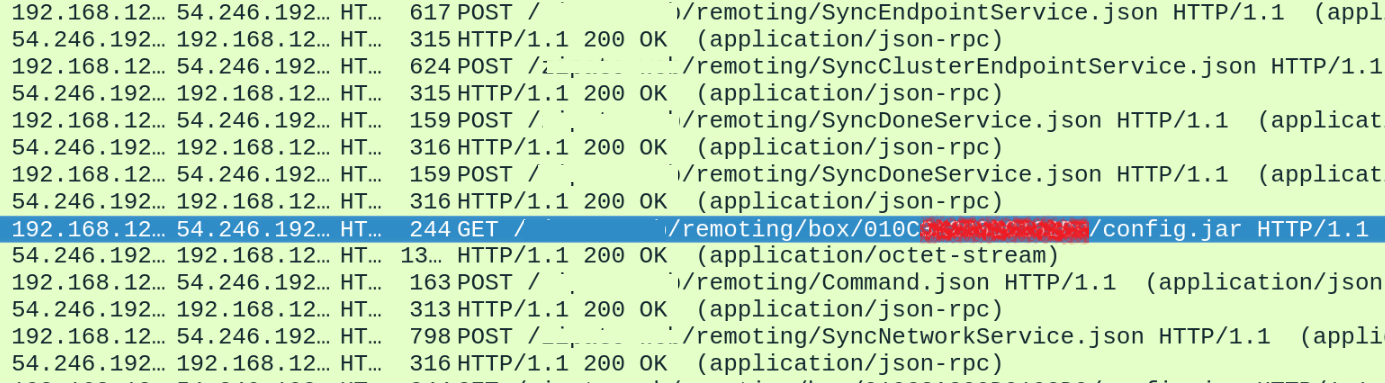

To implement it, the owner sends a command for synchronization with the hub. At that moment, all settings are packed in the config.jar file, which the hub then downloads and implements.

But as we can see, the config.jar file is sent through HTTP and the device’s serial number is used as the device identifier. So, hackers can send the same request with an arbitrary serial number, and download an archive.

Some might think that serial numbers are very unique, but developers prove otherwise: serial numbers are not very well protected and can be brute-forced with a byte selection approach. To check the serial number, remote attackers can send a specially crafted request, and depending on the server’s reply, will receive information if the device is already registered in the system.

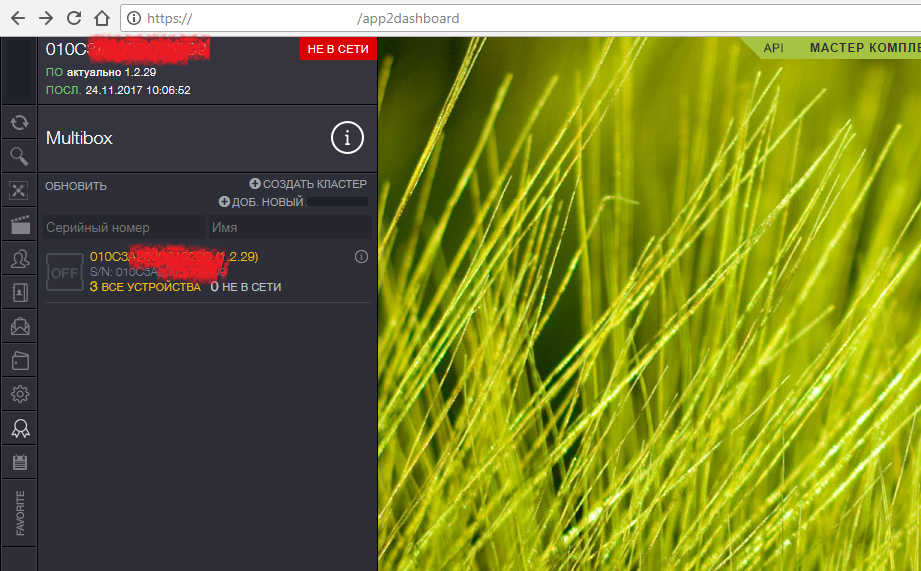

Moreover, our initial research has shown that users, without even realizing it, put themselves at risk by publishing their tech reviews online or posting photos of a hub in social networks and openly presenting devices’ serial numbers. And the security consequences will not be long in coming.

While analyzing the config.jar file archive, we found that it contains login and password details – all the necessary data to access a user’s account through the web-interface. Although the password is encrypted in the archive, it can be broken by hash decryption with the help of publicly available tools and open-sourced password databases. Importantly, during the initial registration of a user account in the system, there are no password complexity requirements (length, special characters, etc.). This makes password extraction easier.

As a result, we gained access to a user’s smart home with all the settings and sensor information being available for any changes and manipulations. The IP address is also listed there.

It is also possible that there might be other personal sensitive information in the archive, given the fact that users often upload their phone numbers into the system to receive alerts and notifications.

Thus, the few steps involved with generating and sending the right requests to the server can provide remote attackers with the possibility of downloading data to access the user’s web interface account, which doesn’t have any additional security layers, such as 2FA (Two Factor Authentication). As a result, attackers can take control over someone’s home and turn off the lights or water, or, even worse, open the doors. So, one day, someone’s smart life could be turned into a complete nightmare. We reported all the information about the discovered vulnerabilities to the vendor, which are now being fixed.

But there is always light at the end of the tunnel…

In addition to smart “boxes”, we had something smaller in our pocket – a smart light bulb, which doesn’t have any critical use, neither for safety or security. However, it also surprised us with a few – but still worrying – security issues.

The smart bulb is connected to a Wi-Fi network and controlled over a mobile application. To set it up a user needs to first download the mobile application (iOS or Android), switch on the bulb, connect to the Wi-Fi access point created by the bulb and provide the bulb with the SSID and password from a local Wi-Fi network.

From the application, users can switch it ON and OFF, set timers and change different aspect of the light, including its density and color. Our goal was to find out if the device might help an attacker in any way to gain access to a local network, from which it would eventually be possible to conduct an attack.

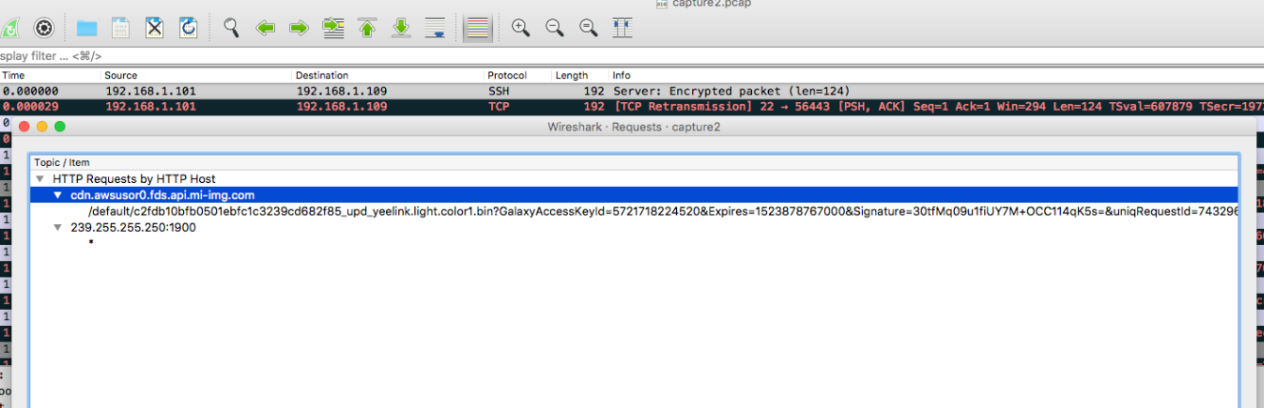

After several attempts, we were lucky to discover a way to get to the device’s firmware through the mobile application. An interesting fact is that the bulb does not interact with the mobile application directly. Instead, both the bulb and the mobile application are connected to a cloud service and communication goes through it. This explains why while sniffing the local network traffic, almost no interaction between the two were found.

We discovered that the bulb requests a firmware update from the server and downloads it through an HTTP protocol that doesn’t secure the communication with servers. If an attacker is in the same network, a man-in-the-middle kind of attack will be an easy task.

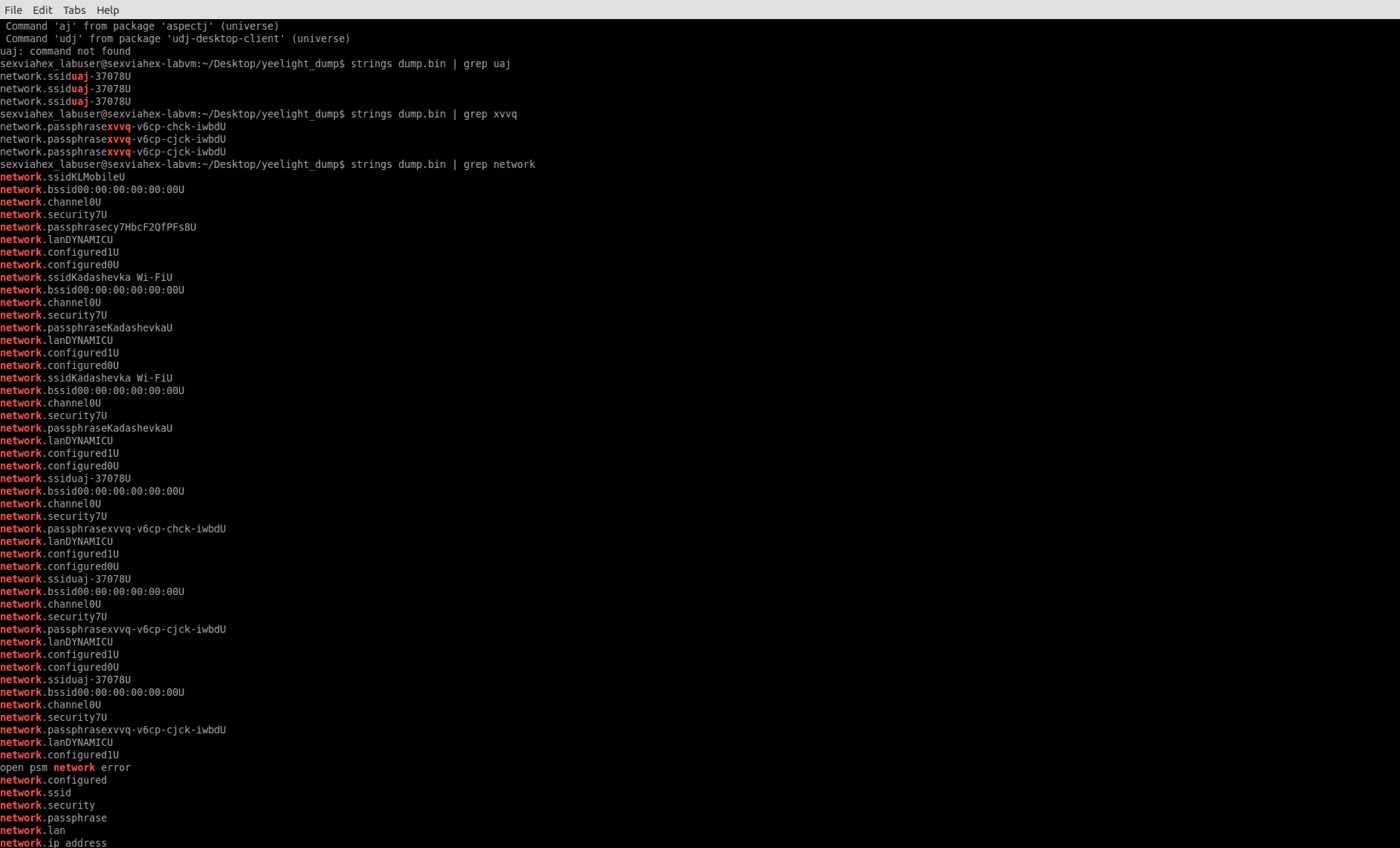

The hardware reconnaissance with flash dumping led us not only to the firmware, but to user data as well. With a quick look at the information shared with the cloud, no sensitive information seems to have been uploaded from the device or the internal network. But we found all the credentials of the Wi-Fi networks to which the bulb had connected before, which are stored in the device’s flash forever with no encryption – even after a “hard” reset of the device this data was still available. Thus, reselling it on online market places is certainly not a good idea.

Get ready

Our latest research has once again confirmed that ‘smart home’ doesn’t mean ‘secure home’. Several logical vulnerabilities (combined with an unconsciously published serial number) can literally open doors to your home and welcome in cybercriminals. Besides this, remote access and control over your smart hub can lead to a wide range of sabotage activities, which could cost you through high electricity bills, a flood or, even more importantly, your mental health.

But even if your smart hub is secure, never forget that the devil is in the details: a tiny thing such as a light bulb could serve as an entry-point for hackers as well, providing them with access to a local network.

That’s why it’s highly important for users to follow these simple cyber hygiene rules:

- Always change the default password. Instead use a strict and complex one. Don’t forget to update it regularly.

- Don’t share serial numbers, IP addresses and other sensitive information regarding your smart devices on social networks

- Be aware and always check the latest information on discovered IoT vulnerabilities.

No less important is that vendors should improve and enhance their security approach to ensure their devices are adequately protected and, as a result, their users. In addition to a cybersecurity check, which is just as vital as testing other features before releasing a product, it is necessary to follow IoT cybersecurity standards. Kaspersky Lab has recently contributed to the ITU-T (International Telecommunication Union — Telecommunication sector) Recommendation, created to help maintain the proper protection of IoT systems, including smart cities, wearable and standalone medical devices and many others.

IoT hack: how to break a smart home… again

Cool8

Helpful !

Anonymous

Why do you not disclose the name of the company that makes this vulnerable product, just like you never, ever disclose information (such as email addresses) of cybercriminals?

AlsoAnonymous

Why don’t you disclose your name and let us all see who you are while were at it

whereupon

What are the real risks to Ma and Pa Kettle? Research is fun, but we all know that true security is based on risk assessment/risk management. What is the probability that an average home in a Chicago suburb will be attacked via the vectors you describe, and what damage would be done? What is the probability that someone would target a house for this attack?

Yousif

How can you get user account information by sending a request to the Hub? Does the Hub reply back with this information or what happens?