A gut feeling of old acquaintances, new tools, and a common battleground

Much has been written about the recent ExPetr/NotPetya/Nyetya/Petya outbreak – you can read our findings here:Schroedinger’s Pet(ya) and ExPetr is a wiper, not ransomware.

As in the case of Wannacry, attribution is very difficult and finding links with previously known malware is challenging. In the case of Wannacry, Google’s Neel Mehta was able to identify a code fragment which became the most important clue in the story, and was later confirmed by further evidence, showing Wannacry as a pet project of the Lazarus group.

To date, nobody has been able to find any significant code sharing between ExPetr/Petya and older malware. Given our love for unsolved mysteries, we jumped right on it.

Analyzing the Similarities

At the beginning of the ExPetr outbreak, one of our team members pointed to the fact that the specific list of extensions used by ExPetr is very similar to the one used by BlackEnergy’s KillDisk ransomware from 2015 and 2016 (Anton Cherepanov from ESET made the same observation on Twitter).

The BlackEnergy APT is a sophisticated threat actor that is known to have used at least one zero day, coupled with destructive tools, and code geared towards attacking ICS systems. They are widely confirmed as the entity behind the Ukraine power grid attack from 2015 as well as a chain of other destructive attacks that plagued that country over the past years.

If you are interested in reading more about the BlackEnergy APT, be sure to check our previous blogs on the topic:

- BE2 custom plugins, router abuse and target profiles

- BE2 extraordinary plugins

- BlackEnergy APT Attacks in Ukraine employ spearphishing with Word documents

Going back to the hunt for similarities, here’s how the targeted extensions lists looks in ExPetr and a version of a wiper used by the BE APT group in 2015:

| ExPetr | 2015 BlackEnergy wiper sample |

|

3ds, .7z, .accdb, .ai, .asp, .aspx, .avhd, .back, .bak, .c, .cfg, .conf, .cpp, .cs, .ctl, .dbf, .disk, .djvu, .doc, .docx, .dwg, .eml, .fdb, .gz, .h, .hdd, .kdbx, .mail, .mdb, .msg, .nrg, .ora, .ost, .ova, .ovf, .pdf, .php, .pmf, .ppt, .pptx, .pst, .pvi, .py, .pyc, .rar, .rtf, .sln, .sql, .tar, .vbox, .vbs, .vcb, .vdi, .vfd, .vmc, .vmdk, .vmsd, .vmx, .vsdx, .vsv, .work, .xls |

.3ds, .7z, .accdb, .accdc, .ai, .asp, .aspx, .avhd, .back, .bak, .bin, .bkf, .cer, .cfg, .conf, .crl, .crt, .csr, .csv, .dat, .db3, .db4, .dbc, .dbf, .dbx, .djvu, .doc, .docx, .dr, .dwg, .dxf, .edb, .eml, .fdb, .gdb, .git, .gz, .hdd, .ib, .ibz, .io, .jar, .jpeg, .jpg, .jrs, .js, .kdbx, .key, .mail, .max, .mdb, .mdbx, .mdf, .mkv, .mlk, .mp3, .msi, .my, .myd, .nsn, .oda, .ost, .ovf, .p7b, .p7c, .p7r, .pd, .pdf, .pem, .pfx, .php, .pio, .piz, .png, .ppt, .pptx, .ps, .ps1, .pst, .pvi, .pvk, .py, .pyc, .rar, .rb, .rtf, .sdb, .sdf, .sh, .sl3, .spc, .sql, .sqlite, .sqlite3, .tar, .tiff, .vbk, .vbm, .vbox, .vcb, .vdi, .vfd, .vhd, .vhdx, .vmc, .vmdk, .vmem, .vmfx, .vmsd, .vmx, .vmxf, .vsd, .vsdx, .vsv, .wav, .wdb, .xls, .xlsx, .xvd, .zip |

Obviously, the lists are similar in composition and formatting, but not identical. Moreover, older versions of the BE destructive module have even longer lists. Here’s a snippet of an extensions list from a 2015 BE sample that is even longer:

Nevertheless, the lists were similar in the sense of being stored in the same dot-separated formats. Although this indicated a possible link, we wondered if we could find more similarities, especially in the code of older variants of BlackEnergy and ExPetr.

We continued to chase that hunch during the frenetic early analysis phase and shared this gut feeling of a similarity between ExPetr and BlackEnergy with our friends at Palo Alto Networks. Together, we tried to build a list of features that we could use to make a YARA rule to detect both ExPetr and BlackEnergy wipers.

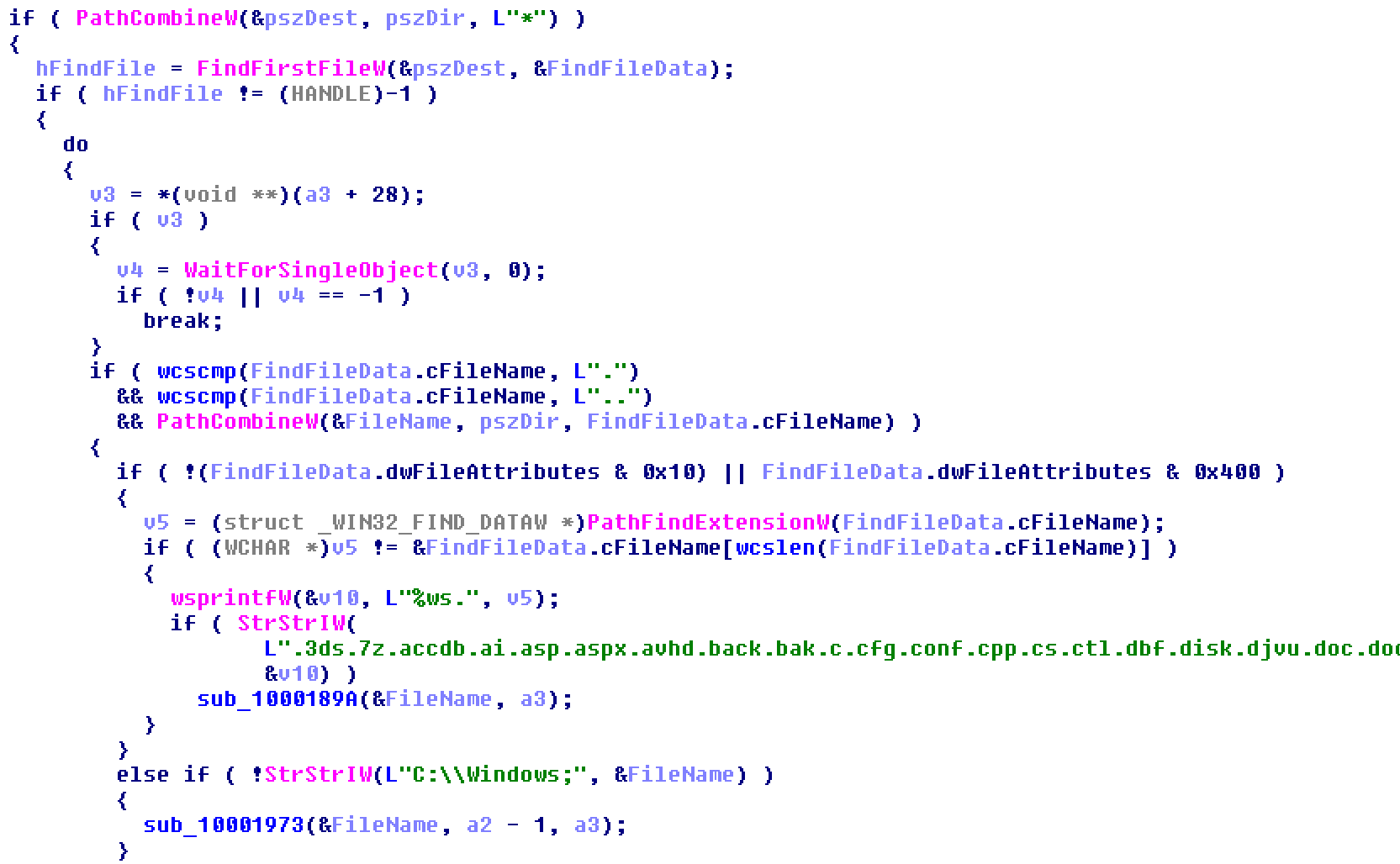

During the analysis, we focused on the similar extensions list and the code responsible for parsing the file system for encryption or wiping. Here’s the code responsible for checking the extensions to target in the current version of ExPetr:

This works by going through the target file system in a recursive way, then checking if the extension for each file is included in the dot-separated list. Unfortunately for our theory, the way this is implemented in older BlackEnergy variants is quite different; the code is more generic and the list of extensions to target is initialized at the beginning, and passed down to the recursive disk listing function.

Instead, we took the results of automated code comparisons and paired them down to a signature that perfectly fit the mould of both in the hope of unearthing similarities. What we came up with is a combination of generic code and interesting strings that we put together into a cohesive rule to single out both BlackEnergy KillDisk components and ExPetr samples. The main example of this generic code is the inlined wcscmp function merged by the compiler’s optimization, meant to check if the filename is the current folder, which is named “.”. Of course, this code is pretty generic and can appear in other programs that recursively list files. It’s inclusion alongside a similar extension list makes it of particular interest to us –but remains a low confidence indicator.

Looking further, we identified some other candidate strings which, although not unique, when combined together allow us to fingerprint the binaries from our case in a more precise way. These include:

- exe /r /f

- ComSpec

- InitiateSystemShutdown

When put together with the wcscmp inlined code that checks on the filename, we get the following YARA rule:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 |

rule blackenergy_and_petya_similarities { strings: //shutdown.exe /r /f $bytes00 = { 73 00 68 00 75 00 74 00 64 00 6f 00 77 00 6e 00 2e 00 65 00 78 00 65 00 } //ComSpec $bytes01 = { 43 00 6f 00 6d 00 53 00 70 00 65 00 63 00 } //InitiateSystemShutdown $bytes02 = { 49 6e 69 74 69 61 74 65 53 79 73 74 65 6d 53 68 75 74 64 6f 77 6e 45 78 57} //68A4430110 push 0100143A4 ;'ntdll.dll' //FF151CD10010 call GetModuleHandleA //3BC7 cmp eax,edi //7420 jz ... $bytes03 = { 68 ?? ?? ?1 ?0 ff 15 ?? ?? ?? ?0 3b c7 74 ?? } // "/c" $bytes04 = { 2f 00 63 00 } //wcscmp(... $hex_string = { b9 ?? ?? ?1 ?0 8d 44 24 ?c 66 8b 10 66 3b 11 75 1e 66 85 d2 74 15 66 8b 50 02 66 3b 51 02 75 0f 83 c0 04 83 c1 04 66 85 d2 75 de 33 c0 eb 05 1b c0 83 d8 ff 85 c0 0f 84 ?? 0? 00 00 b9 ?? ?? ?1 ?0 8d 44 24 ?c 66 8b 10 66 3b 11 75 1e 66 85 d2 74 15 66 8b 50 02 66 3b 51 02 75 0f 83 c0 04 83 c1 04 66 85 d2 75 de 33 c0 eb 05 1b c0 83 d8 ff 85 c0 0f 84 ?? 0? 00 00 } condition: ((uint16(0) == 0x5A4D)) and (filesize < 5000000) and (all of them) } |

When run on our extensive (read: very big) malware collection, the YARA rule above fires on BlackEnergy and ExPetr samples only. Unsurprisingly, when used alone, each string can generate false positives or catch other unrelated malware. However, when combined together in this fashion, they become very precise. The technique of grouping generic or popular strings together into unique combinations is one of the most effective methods for writing powerful Yara rules.

Of course, this should not be considered a sign of a definitive link, but it does point to certain code design similarities between these malware families.

This low confidence but persistent hunch is what motivates us to ask other researchers around the world to join us in investigating these similarities and attempt to discover more facts about the origin of ExPetr/Petya. Looking back at other high profile cases, such as the Bangladesh Bank Heist or Wannacry, there were few facts linking them to the Lazarus group. In time, more evidence appeared and allowed us, and others, to link them together with high confidence. Further research can be crucial to connecting the dots, or, disproving these theories.

We’d like to think of this ongoing research as an opportunity for an open invitation to the larger security community to help nail down (or disprove) the link between BlackEnergy and ExPetr/Petya. Our colleagues at ESET have published their own excellent analysis suggesting a possible link between ExPetr/Petya and TeleBots (BlackEnergy). Be sure to check out their analysis. And as mentioned before, a special thanks to our friends at Palo Alto for their contributions on clustering BlackEnergy samples.

Hashes

ExPetr:

027cc450ef5f8c5f653329641ec1fed91f694e0d229928963b30f6b0d7d3a745

BE:

11b7b8a7965b52ebb213b023b6772dd2c76c66893fc96a18a9a33c8cf125af80

5d2b1abc7c35de73375dd54a4ec5f0b060ca80a1831dac46ad411b4fe4eac4c6

F52869474834be5a6b5df7f8f0c46cbc7e9b22fa5cb30bee0f363ec6eb056b95

368d5c536832b843c6de2513baf7b11bcafea1647c65df7b6f2648840fa50f75

A6a167e214acd34b4084237ba7f6476d2e999849281aa5b1b3f92138c7d91c7a

Edbc90c217eebabb7a9b618163716f430098202e904ddc16ce9db994c6509310

F9f3374d89baf1878854f1700c8d5a2e5cf40de36071d97c6b9ff6b55d837fca

From BlackEnergy to ExPetr