All statistical data used in this report were obtained using Kaspersky Lab’s botnet monitoring system and Kaspersky DDoS Prevention.

H2 2011 in figures

- In the second half of 2011, the maximum attack power repelled by Kaspersky DDoS Prevention went up 20% compared to the first half of the year, and amounted to 600 Mbit/sec, or 1,100,000 packets/sec (UDP flood with short packets of 64 bytes).

- The average attack prevented by Kaspersky DDoS Prevention in the second half of 2011 was 110 Mbit/sec – an increase of 57%.

- The longest DDoS attack in the second half of the year lasted for 80 days, 19 hours, 13 minutes and 5 seconds, and targeted a travel website.

- The average duration of a DDoS attack was 9 hours, 29 minutes.

- The largest number of DDoS attacks in the second half of 2011 – 384 in number – targeted a cybercriminal portal.

- DDoS attacks were launched from computers located in 201 countries around the world.

The events of H2 2011

Finance: DDoS attacks on stock exchanges

Stock markets are challenging places to do business: participants must be able to analyze the present situation, predict how things will unfold for the entire market and for the companies whose shares they are interested in, and react swiftly to breaking news. All this is feasible only if all parties can get the latest information in a timely manner. However, if people can “jump the queue” and ensure they are always first with the news, this can generate a very good profit. One way of staying ahead of the competition is by arranging DDoS attacks, as we saw in late summer 2011.

On 10 August, a DDoS attack was launched against a Hong Kong stock exchange website. Interestingly, the attackers did not target the stock exchange’s main site, but one which publishes important announcements from the market’s largest players. As a result, trading in the shares of seven companies, including HSBC, Cathay Pacific, China Power International and associated derivatives, had to be suspended. The site stayed offline for a further day, and trading in the dependent positions was also suspended. It is practically impossible to estimate the associated losses and profits; however, it is clear that somebody tried to make money out the disruption.

Naturally, the attack was implemented with the help of a botnet, and finding the culprit in such circumstances is no easy task. However, considering how much money circulates in the stock market and the potential impact on the reputation of HKEX, which is the fifth largest stock exchange in the world, Hong Kong’s law enforcement agencies launched an extensive investigation. Within two weeks it was announced that a man had been arrested on suspicion of organizing the attack. The arrested 29-year-old turned out to be a businessman gambling on the stock exchange. He now faces up to five years in prison for the DDoS attack – plenty of time to think about other, more legitimate business strategies.

DDoS attacks and political protests

The notorious Anonymous group was once again making headlines in the second half of 2011. After the police used tear gas and rubber bullets on protestors supporting the Occupy Wall Street movement, a new campaign called Occupy Oakland was arranged. A DDoS attack launched as a part of that campaign put Oakland’s police website out of action, and confidential police data was published on the web.

Anonymous later attacked government sites in El Salvador. This was the group’s response to claims that the Salvadoran authorities were guilty of numerous human rights violations.

After an Israeli task force intercepted a vessel carrying humanitarian supplies approaching the coast of Gaza, members of the Anonymous group published a video clip on YouTube in which they warned about protest attacks they were preparing. Two days later, the sites of Israel’s Defense Forces, and the Mossad and the Shen Bet intelligence services were unavailable. However, Israel’s government did not confirm the Anonymous attack and said that the sites were unavailable due to server malfunctions.

Although Anonymous has become the talk of the town, it does not accept responsibility for all high-profile political attacks. In September, unknown cybercriminals carried out a DDoS attack on the Russian Embassy in London. The attack took place the day before the British prime minister visited Moscow, a visit which apparently provoked the attackers’ displeasure.

DDoS attacks and small businesses

In the past six months, we have observed two big waves of DDoS attacks launched on travel company sites. The first wave took place during the summer vacations when many users were busy looking for seaside holiday options. (Also during this period, cybercriminals ordered DDoS attacks on websites offering beach resort apartments for rent or sale.)

The second wave of attacks occurred during the Christmas and New Year holidays. This time, most of the targeted sites were offering vacations with a festive theme.

There were no large travel operators among the victims of these attacks. All the DDoS incidents targeted tour agencies. It’s worth noting that there are many more agencies than operators, and the competition between them is much tougher.

The number of attacks on tour agency websites increases fivefold in the peak season, as compared to low season. It is safe to say that the sites attacked during both the summer and winter waves became victims of ‘contract hits’: what we are seeing is basically cyber warfare between tourist agencies. Revealingly, the waves of DDoS attacks coincide with spam mailings advertising the services of tourist agencies. All of this suggests that the competition in the travel business is so fierce that some players will go to any length to attract clients.

It is interesting to note that the second half of the year saw a dramatic rise in the number of attacks on sites offering taxi bookings or printer cartridge refilling services. These services were also advertised with the help of mass mailing. It seems that companies ordering such mass mailings have connections with the bot masters and may well be the ones ordering DDoS attacks that target the sites of their competitors.

Crime and Punishment

In October, the story of DDoS attacks launched on the payment service ASSIST continued to unfold. Pavel Vrublevsky, the owner of the processing center ChronoPay and the chief suspect behind those particular DDoS attacks, pleaded guilty to organizing them. You may recall that the attacks disrupted online ticket sales of Aeroflot, Russia’s largest airline.

It looks like the owner of ChronoPay wanted to discredit his competitor’s services and used the DDoS attacks to lure blue-chip clients like Aeroflot away from ASSIST, thus increasing his own company’s already healthy (40%) share in the payment processing market. The attack began on 16 July, 2010; only after a week of shutdowns was Aeroflot able to restore online ticket sales. The attempts by ASSIST to combat the attack could not prevent the loss of an important client – Aeroflot switched to a contract with Alfa Bank.

Pavel Vrublevsky is facing charges under Articles 272 and 273 of Russia’s Criminal Code, and faces a sentence of up to seven years in prison.

Some members of the Anonymous group have also faced prosecution from law enforcement agencies. Hacktivists were arrested in Turkey, Italy, Spain, Switzerland, the UK and the USA. It proved easy to track down those who had participated in attacks using the open-source LOIC (Low Orbit Ion Canon) tool. This tool was created without malicious intent to produce a test load on a web server. As a result, it does not contain any functions to conceal the addresses from which attacks originate, meaning logs can be viewed and the respective Internet providers can be contacted. In other cases it may not be so easy to track down the hacktivists. However, it would be naive to expect that the offenders could get away with the DDoS attacks and hacks they have arranged on government sites. Notably, the average age of those arrested is about 20.

Combating botnets is only possible if there is close cooperation between law enforcement agencies, antivirus developers and software vendors.

Cybercriminal infighting

DDoS attacks are not just a means of unfair competition in the traditional market of physical commodities and services but also in the murky world of the cybercrime business. Since all cybercriminal operations take place on the Internet, DDoS attacks are a very effective tool with which to exert pressure on competitors.

In the second half of the year, the greatest number of attacks (384) was launched against an online resource selling forged documents. Generally, it is carders and their colleagues who most often resort to DDoS attacks: the bots attack forums where related topics are discussed, as well as sites where cardholders’ personal data are sold. The next most popular group of victims of DDoS attacks are sites offering bullet-proof hosting and VPN services for cybercriminals. This demonstrates that there is intense competition among cybercriminals, and that DDoS botnets are freely available to them.

New techniques in DoS/DDoS attacks

Google+

At the end of August the Italian researcher Simone “ROOT_ATI” Quatrini of AIR Sicurezza Informatica cited two special Google+ URL services in the blog IHTeam Security with which cybercriminals can use Google servers to launch a DoS attack on any site: https://plus.google.com/_/sharebox/linkpreview/ and https://images2-focus-opensocial.googleusercontent.com/gadgets/proxy?

The former is a tool for previewing web pages, while the latter is a gadget with which to use hotlinks and keep cache copies of files on Google servers. When using these two tools, one can send a parameter within the URL containing a link to any file located on the site to be attacked. In this case, Google servers will request the file and then send it to the user, i.e. they act as a proxy. Automatic tools (such as a script) can be used to send a multitude of such requests; multiplied by Google’s bandwidth capacity, this will effectively amount to a HTTP DDoS attack on the victim site.

The researcher noted in his description that this method allows the attacker to keep their identity anonymous. However, when the second URL is used, the attacker’s IP address is sent to the requested site in a field of the HTTP request, so an attack from a specific IP address can be easily blocked by the server under attack.

After the researcher sent the description of these “vulnerabilities” to Google Security Team, Google closed the first page /_/sharebox/linkpreview/, but left the second one gadgets/proxy? unchanged. Apparently, the service designers did not consider the possible use of this page for a DDoS attack to be a serious problem, since such an attack can easily be repelled.

In general, however, it is unlikely that public services will ever be broadly used as a tool to launch serious DDoS attacks, because such vulnerabilities will be quickly fixed by service providers as soon as they become known.

THC-SSL-DOS

Recently, researchers’ attention has been increasingly drawn to the cases when effective DDoS attacks can be launched with minimum effort from the attacker, i.e. without using large botnets. This could herald a shift from conventional DDoS attacks using large amounts of traffic, to attacks that lead to exploiting large resources on the server under attack. The attack type described below perfectly fits this model.

In October, the German research team The Hacker’s Choice released new proof-of-concept software for carrying out DoS attacks on web servers by taking advantage of a peculiarity in the SSL protocol. With the new tool called THC-SSL-DOS, a single computer can crush an average-configuration server if the server supports SSL renegotiation. This option enables the web server to create a new secret key on top of the existing SSL connection. It is seldom used, but it is typically enabled by default on most servers. Establishing a secure connection and the execution of SSL renegotiation requires much more resources on the server side than on the client side. This asymmetry is duly exploited: if the client sends a multitude of SSL renegotiation requests, this overwhelms the server’s resources. The worst attack scenario involves a multitude of attacking clients (the SSL-DDoS scenario).

It should be noted that not all web servers are vulnerable to this type of attacks: some web servers, such as IIS web server, do not support SSL renegotiations initiated by the client. Also, web servers may use SSL acceleration as a countermeasure that will protect the web server from an excessive computation load.

Some software vendors do not see a serious problem in the above method of attack. If the SSL renegotiation option cannot be disabled altogether, they recommend setting ad-hoc rules for breaking connections with clients who request SSL renegotiations more than a limited number of times in a set period of time.

The program’s creators maintain that even if a server does not support SSL renegotiation, it can still be attacked using a modified version of their program. In this case, a multitude of TCP connections is established for every new SSL handshaking; however, more bots may be required for an effective attack.

The authors say that they have released this tool in hope of attracting attention to “questionable SSL security”. They write in their blog: “The industry should step in to fix the problem so that citizens are safe and secure again. SSL is using an aging method of protecting private data which is complex, unnecessary and not fit for the 21st century.”

Apache Killer

In August a critical vulnerability was detected in the popular web server Apache HTTPD that enabled cybercriminals to exhaust server resources through incorrect processing of the HTTP header Range: Bytes. This field enables the client to download files piecemeal by using the specified byte ranges. When processing a large number of ranges, Apache consumes a lot of memory, applying gzip compression to each range. This may ultimately lead to service failures unless the web server configuration limits the memory allocated for the process. The vulnerable Apache versions are versions 2.0.x, including 2.0.64, and 2.2.x, including 2.2.19.

Apache also announced that this DoS attack was actively exploited using a perl script that was widespread on the Internet. Until a security patch is released, the security specialists recommended that system administrators include specific settings in server configurations that would help detect multiple range requests, after which the Range field could be ignored, or the entire request could be rejected.

At the present time, this vulnerability has been fixed in versions 2.2.20 and 2.2.21; however, version 2.0.65 with security updates has not yet been released.

Vulnerable hash tables

In 2003, researchers from Rice University released a paper entitled Denial of Service via Algorithmic Complexity Attacks, in which they described the idea of a DoS attack targeting applications that use hash tables. The idea was that if an application does not use a randomized hash function in its hash table implementation, then an attacker can choose a large number of colliding keys and “feed” them to the application. As a result, the complexity of the algorithm used to insert a “key-value” pair increases tenfold, leading to increased consumption of CPU time. Although this problem was reported a sufficiently long time ago, nobody developed proof-of-concept code demonstrating practical possibilities of an attack. Not until late 2011.

Two researchers from Germany presented a paper at the Chaos Congress Conference, in which they revisited the old problem of hash tables and DoS. The paper described an attack which takes advantage of vulnerabilities in many web programming languages, including PHP, ASP.NET, Java, Python and Ruby. All of these platforms use similar hashing algorithms where it is possible to find collisions. In order to take a server down, an attacker can send a POST request to a web application created using one of the technologies listed above. The request should include specially selected parameters for a web form etc. that will result in multiple collisions. As a rule, web applications use hash tables to store parameters passed to them. In their paper, researchers tested their proof-of-concept attack on vulnerable platforms and cited theoretical and real-life times required to process malicious POST requests for different platforms. Generally, depending on the platform, server configuration and the amount of data in the POST request, one request can occupy the CPU for a time period ranging from several minutes to several hours. And with a series of such requests, attackers can take down a multiple-core server or even a server cluster.

The Germans also noted that such POST requests to a server that is under attack can in theory be generated on-the-fly by HTML or JavaScript code on some third-party website – like in cross-site scripting (XSS) attacks. As a result, a large number of users can indirectly participate in a distributed DoS attack.

It is also worth noting that one of the slides in the presentation included an image of the mask used by the infamous Anonymous group, a transparent hint that the group has already been involved in numerous DDoS attacks and is not averse to adopting new technologies.

Before the official presentation was made at the conference, all the ‘vulnerable’ programming language vendors were notified of the problem in November.

Microsoft was quick to respond to the threat by releasing a patch for ASP.NET, which limits the number of parameters that can be sent in one POST request. The release of the patch was expedited due to Microsoft’s fears (not without cause) that somebody would make an exploit for the vulnerability publicly available. The release of the patch was well timed: in early 2012, a user going by the nickname HybrisDisaster published a set of colliding keys for ASP.NET.

Ruby developers released new versions of CRuby and JRuby with randomized hash functions. As regards PHP, the only change so far has been to introduce a new variable, max_input_vars, which limits the number of parameters in POST requests.

Importantly, Perl 5.8.1 and CRuby 1.9 have been immune to this attack since 2003 and 2008 respectively, because they already use randomized hash functions.

The mysterious RefRef

In late July Anonymous presented something new, known as RefRef which, according to the group, could be used to conduct DDoS attacks. It replaced LOIC, which had previously been used for the same purpose.

It is well known that Anonymous used LOIC in their numerous attacks on government websites, the sites of organizations that were opposed to WikiLeaks, and other organizations’ web resources. As mentioned above, over 30 participants of attacks that involved LOIC were subsequently arrested: many of the attackers failed to conceal their IP addresses and were thus easy to identify.

News sites and blogs were quick to spread information about the new DDoS tool. It was even mentioned by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security in its security bulletin on potential threats and upcoming attacks by Anonymous.

Despite information about the new DDoS tool being distributed widely, nobody knew accurate details of its implementation. Vague statements by its ‘developers’ had been published, from which it followed that the program was written in Java or perhaps in JavaScript, that it exploited some SQL injection vulnerability on most websites, or could upload its own js files to the server in some way. And the website was supposed to crash due to exhaustion of server resources – CPU or RAM or both.

Anonymous also announced that RefRef had been tested on PasteBin and WikiLeaks. The former confirmed an attack and even tweeted a request to stop attacking the resource:

It was unclear to many people why Anonymous would want to attack WikiLeaks: Anonymous had supported the resource since the group’s inception. The group’s representative @AnonCMD claimed responsibility for the attack. He claimed to be the developer of RefRef and explained that the attack was due to “monetary disputes” between him and WikiLeaks head Julian Assange.

After the “announcement” of the new DDoS tool, things progressed rapidly. The refref.org website was created. The site, which has now been closed down , was reportedly affiliated with the developers of the DDoS tool after which it was named. Several fake scripts appeared under the name of RefRef. The most widespread of these was a script in Perl, which can be used only against those sites which have an SQL injection vulnerability. It is worth noting that for an attack to be successful, the attacker must first find a vulnerable website – the script only performs a select benchmark-type command on the server. This means that the script cannot be used to attack most websites. However, IBM Internet Security Systems, quickly reacting to this script as a new threat to the security of many sites, posted a special security warning on their website and released an IPS signature for their products.

Members of Anonymous repeatedly dismissed any connection with the fakes and promised to release the real RefRef on 17 September. However, no release followed. Subsequently both the group as a whole and @AnonCMD in particular were widely accused of lying. @AnonCMD had advertised his tool to his Anonymous “colleagues”, hailing its “triumphant progress”. Later he admitted that RefRef had never existed.

The simple conclusion of the story is that some Anonymous representatives are trying to attract as much attention to the group as a whole and themselves in particular, and the mass media lend them a helping hand by spreading rumors and unverified information.

Statistics

Distribution of DDoS attack sources by country

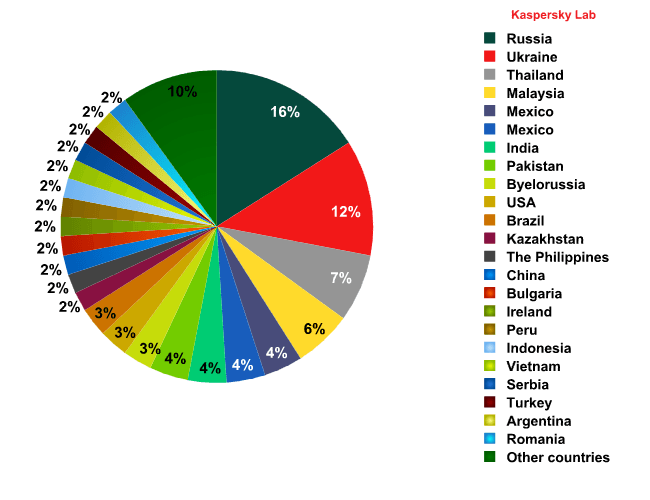

During the six-month period, our systems detected attacks on computers in 201 countries across the globe. However, 90% of all DDoS traffic came from 23 countries.

Distribution of DDoS traffic sources by country – H2 2011

The geographical distribution of sources of DDoS attacks targeting Russian websites has changed. At the end of the first half of 2011, the top positions in the ranking were occupied by the United States (11%), Indonesia (5%) and Poland (5%). The second half of the year has produced several new leaders: Russia (16%), Ukraine (12%), Thailand (7%) and Malaysia (6%). The contribution of zombie computers from 19 other countries ranges between 2% and 4%.

In Russia and Ukraine, we detected new botnets created using programs sold on underground forums. Curiously, these botnets were attacking targets located in the same countries as the botnets. Before this, we mostly detected attacks in which the bots and the servers they attacked were located in different countries.

The evident change in traffic distribution, as well as Russia and Ukraine joining the leaders, was in part due to the active use of certain anti-DDoS measures. Specifically, one method of blocking DDoS attacks is filtering traffic based on the source countries. The idea is very simple: when a DDoS attack is detected, this triggers a system that rejects all data packets except those coming from a specific country. As a rule, only users from the country where the majority of the site’s audience is located are allowed access to the resource. This is why cybercriminals have to create botnets in specific countries and use them to attack resources in these same countries to prevent their traffic from being filtered.

At the same time, those botnets which operate based on the “classical” approach, when attacks are conducted using resources outside the country where the under-fire server is located, remain operational. Thailand and Malaysia are good examples of countries where there are large numbers of unprotected computers, while it appears that bot masters receive relatively few orders to attack websites in these countries. This means that the region is a good place for cybercriminals to set up botnets.

The countries accounting for 2-4% of all DDoS attacks also changed from the first half of the year. This group includes only three countries with high levels of computer penetration and IT security: Ireland (2%), the United States (3%) and Poland (4%). The remaining generators of junk traffic were infected computers in developing countries, where the number of computers per capita is much smaller, while IT security is not particularly strong: Mexico (4%), India (4%), Pakistan (4%), Belarus (3%), Brazil (3%) etc.

Distribution of sites attacked by type of online activity

The online trade segment (online shops, auctions, message boards for sale ads etc.) retained its leading position: these sites suffered 25% of all registered attacks.

Towards the New Year, the number of DDoS attacks on websites offering various goods began to increase. Targets most frequently included shops selling small household items, home appliances, electronics, designer clothes for children and adults, as well as accessories and expensive jewelry.

Electronic trading sites are in second position. Making money through dishonest tricks is nothing new in the financial world and DDoS attacks come in handy. It is worth noting that in the second half of the year hackers were interested in websites through which government-owned and municipal institutions place their orders.

Gaming sites accounted for 15% of all DDoS attacks, which is 5 percentage points less than in the second quarter of 2011. Attacks primarily targeted sites that offer game server hosting services. These are followed, in terms of the number of attacks, by servers (mostly owned by software pirates) offering various online games. The largest number of attacks targeted the servers of the Lineage2 MMORPG and those hosting various clones of Minecraft, a game that became very popular in the last months of the year.

Mass media accounted for 2% of all DDoS attacks. Targets of these attacks included websites of television channels and publishers of newspapers and magazines in several former Soviet republics.

The proportion of attacks on government-owned websites is gradually increasing. It reached 2% in the second half of 2011. Attacks mostly targeted official websites of regional governments or big cities. The motivation behind attacks on government sites may vary, but in most cases attacks are conducted in protest against the actions, or inaction, of the authorities.

Types of DDoS attacks

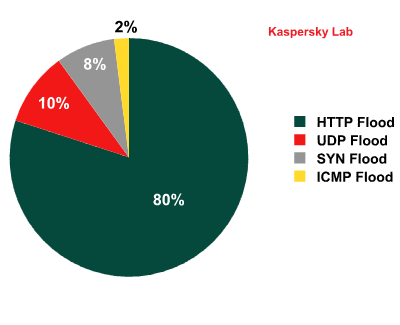

In the second half of 2011, Kaspersky Lab’s botnet monitoring system intercepted over 32,000 web-borne commands to initiate attacks on different sites.

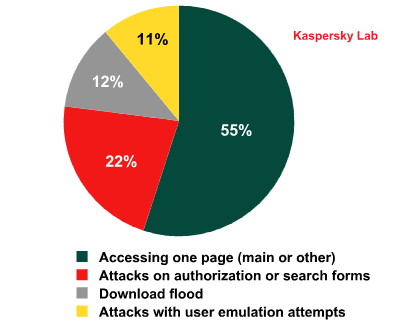

Types of DDoS attacks – H2 2011

Types of HTTP Flood – H2 2011

HTTP Flood remains the most popular type of attack (80%). It involves simultaneously sending a large number of HTTP requests to the site being attacked. Cybercriminals use several different technologies to conduct this type of attack. In 55% of all HTTP Flood attacks bots try to access a single page of the site. The second most common type (22%) is attacks on various authorization forms. The third most common type (12%) is attacks that involve numerous attempts to download a file from the site. More sophisticated attacks, in which cybercriminals attempt to mask the bots by imitating the behavior of real users, are conducted in only 10% of all cases.

The second most common type of DDoS attack (10%) is UDP Flood attacks. The bots conducting these attacks rely on “brute force”: they generate enormous numbers of garbage packets that are relatively small (e.g. 64 bytes in size).

The third and fourth positions in the popularity ranking are occupied by SYN Flood (8%) and ICMP Flood (2%) attacks respectively.

Activity of DDoS botnets over time

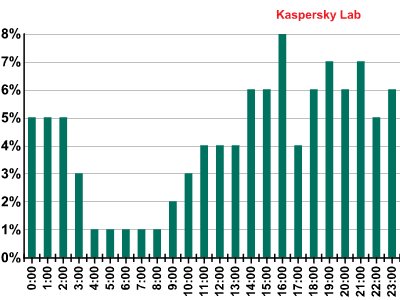

We have analyzed at what time of day DDoS bots most commonly attack various sites. The diagram below shows attacks in local time, i.e. for the time zones of the sites being attacked.

Breakdown of DDoS attacks by hours of the day – H2 2011

Judging by the diagram, DDoS bots start working around 9 or 10 am, when site visitors arrive at work and start using the Internet for business-related purposes. The peak of activity is at 4 pm. However, bots put in long working hours, with the majority of botnets going to sleep around 4 o’clock in the morning.

Conclusion

We were right when we predicted in our Q2 report that the number of DDoS attacks in protest against government decisions would increase. The activity of the Anonymous group has not abated despite the arrests of the group’s members. In addition, DDoS attacks as a form of protest are joined by groups which, unlike Anonymous, prefer to remain in the shadows. For example, attacks on the websites of political parties, political projects and various mass media were recorded in Russia in the run-up to December’s general elections, but those who ordered the attacks did not identify themselves in any way.

The number of machines in DDoS botnets is gradually growing, resulting on average in more powerful attacks (a growth of 57% in six months). However, higher power has a side effect to it: such botnets attract the attention of anti-DDoS projects and law enforcement agencies, which can make such botnets much less attractive to cybercriminals. This is why we are not going to see really large DDoS botnets in 2012. Our radars will show mostly medium-size botnets, which are powerful enough to take down an average website, and such botnets are going to become more numerous. Then, as more companies adopt anti-DDoS protection, hackers will have to increase the power of attacks by using several botnets targeting one resource at once.

Given the demand for DDoS attacks, owners of this illegal business will take care to improve their technologies. The architecture of the zombie networks used for DDoS attacks will get more complicated and P2P networks will displace centralized botnets. In addition, according to current research, in 2012 cybercriminals will look for new ways of conducting DDoS attacks without using botnets.

DDoS attacks in H2 2011