During the first week of October, Kaspersky took part in the 34th Virus Bulletin International Conference, one of the longest-running cybersecurity events. There, our researchers delivered multiple presentations, and one of our talks focused on newly observed activities by the Careto threat actor, which is also known as “The Mask”. You can watch the recording of this presentation here:

The Mask APT is a legendary threat actor that has been performing highly sophisticated attacks since at least 2007. Their targets are usually high-profile organizations, such as governments, diplomatic entities and research institutions. To infect them, The Mask uses complex implants, often delivered through zero-day exploits. The last time we published our findings about The Mask was in early 2014, and since then, we have been unable to discover any further traces of this actor.

The Mask’s new unusual attacks

However, our newest research into two notable targeted attack clusters made it possible to identify several recent cyberattacks that have been, with medium to high confidence, conducted by The Mask. Specifically, we observed one of these attacks targeting an organization in Latin America in 2022. While we do not have any traces allowing us to tell how this organization became compromised, we have established that over the course of the infection, attackers gained access to its MDaemon email server. They further leveraged this server to maintain persistence inside the compromised organization with the help of a unique method involving an MDaemon webmail component called WorldClient.

Implanting the MDaemon server

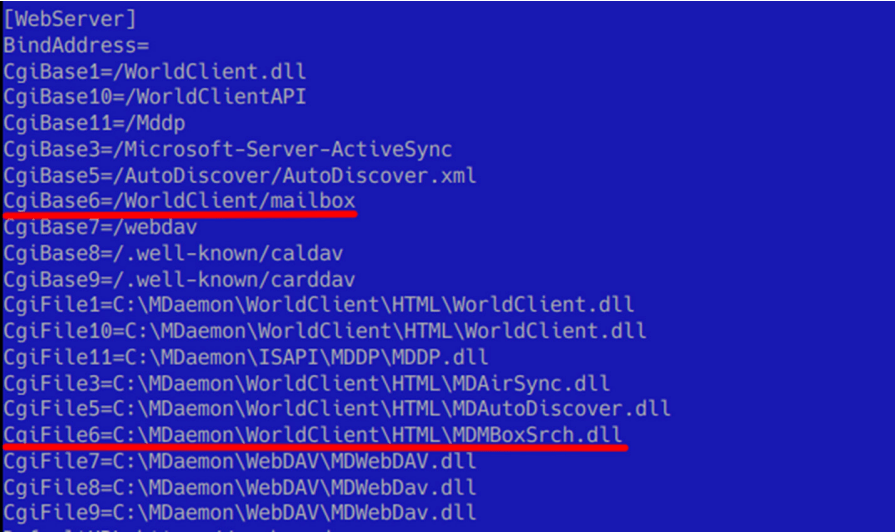

The persistence method used by the threat actor was based on WorldClient allowing loading of extensions that handle custom HTTP requests from clients to the email server. These extensions can be configured through the C:\MDaemon\WorldClient\WorldClient.ini file, which has the format demonstrated in the screenshot below:

As can be observed from the screenshot above, the information about each extension includes a relative URL controlled by the extension (specified in the CgiBase parameter), as well as the path to the extension DLL (in the parameter CgiFile).

To use WorldClient’s extension feature for obtaining persistence, the threat actor compiled their own extension and configured it by adding malicious entries for the CgiBase6 and CgiFile6 parameters, underlined in red in the screenshot. As such, the actor was able to interact with the malicious extension by making HTTP requests to the URL https://<webmail server domain name>/WorldClient/mailbox.

Spreading the FakeHMP implant inside the network

The malicious extension installed by attackers implemented a set of commands associated with reconnaissance, performing file system interactions and executing additional payloads. We observed attackers using these commands to gather information about the infected organization and then spread to other computers inside its network. While investigating the infection that occurred in Latin America in 2022, we established that the attackers used the following files to conduct lateral movement:

- sys, a legitimate driver of the HitmanPro Alert software

- dll, a malicious DLL with the payload to be delivered

- ~dfae01202c5f0dba42.cmd, a malicious .bat file

- Tpm-HASCertRetr.xml, a malicious XML file containing a scheduled task description

To spread to other machines, attackers uploaded these four files and then created scheduled tasks with the help of the Tpm-HASCertRetr.xml description file. When started, these scheduled tasks executed commands specified in the ~dfae01202c5f0dba42.cmd file, which in turn installed the hmpalert.sys driver and configured it to load on startup.

One of the functions of the hmpalert.sys driver is to load HitmanPro’s DLL, placed at C:\Windows\System32\hmpalert.dll, into running processes. However, as this driver does not verify the legitimacy of the DLLs it loads, attackers were able to place their payload DLLs at this path and thus inject them into various privileged processes, such as winlogon.exe and dwm.exe, on system startup.

What was also notable is that we observed attackers using the hmpalert.sys driver to infect a machine of an unidentified individual or organization in early 2024. However, unlike in 2022, the adversary did not use scheduled tasks to do that. Instead, they leveraged a technique involving Google Updater, described here.

The payload contained in the malicious hmpalert.dll library turned out to be a previously unknown implant that we dubbed FakeHMP. Its capabilities included retrieving files from the filesystem, logging keystrokes, taking screenshots and deploying further payloads to infected machines. Apart from this implant, we also observed attackers deploying a microphone recorder and a file stealer to compromised computers.

Same organization, hacked by the Mask in 2019

Having examined available information about the organization compromised in 2022, we found that it was also compromised with an advanced attack in 2019. That earlier attack involved the use of two malicious frameworks which we dubbed “Careto2” and “Goreto”. As for Careto2, we observed the threat actor deploying the following three files to install it:

- Framework loader (placed at %appdata%\Media Center Programs\cversions.2.db);

- Framework installer (named ~dfae01202c5f0dba42.cmd);

- Auxiliary registry file (placed at %temp%\values.reg).

We further found that, just like in the 2022 infection case, attackers used a scheduled task to launch a .cmd file, which in turn configured the framework to persist on the compromised device. The persistence method observed was COM hijacking via the {603d3801-bd81-11d0-a3a5-00c04fd706ec} CLSID.

Regarding the framework itself, it was designed to read plugins stored in its virtual file system, located in the file %appdata%\Media Center Programs\C_12058.NLS. The name of each plugin in this filesystem turned out to be a four-byte value, such as “38568efd”. We have been able to ascertain that these four-byte values were DJB2 hashes of DLL names. This made it possible to brute-force these plugin names, some of which are provided in the table below:

| Plugin DLL name hash | Likely DLL name | Plugin description |

| 38568efd | ConfigMgr.dll | Manages configuration parameters of Careto2. |

| 5ca54969 | FileFilter.dll | Monitors file modifications in specified folders. |

| b6df77b6 | Storage.dll | Manages storage of stolen files. |

| 1c9f9885 | Kodak.dll | Takes screenshots. |

| 82b79b83 | Comm.dll | Uploads exfiltrated data to an attacker-controlled OneDrive storage. |

Regarding the other framework, Goreto, it is a toolset coded in Golang that periodically connects to a Google Drive storage to retrieve commands. The list of supported commands is as follows:

| Command name | Description |

| downloadandexec | Downloads a file from Google Drive, decrypts it, drops it to disk and executes. |

| downloadfile | Downloads a file from Google Drive, decrypts it and drops it to disk. |

| uploadfile | Reads a specified file from disk, encrypts it and uploads it to Google Drive. |

| exec | Executes a specified shell command. |

Apart from the command execution engine, Goreto implements a keylogger and a screenshot taker.

Attribution

As mentioned above, we attribute the previously described attacks to The Mask with medium to high confidence. One of the first attribution clues that caught our attention was several file names used by the malware since 2019, alarmingly similar to the ones used by The Mask more than 10 years ago:

| 2007-2013 attack file names | 2019 attack file names |

| ~df01ac74d8be15ee01.tmp | ~dfae01202c5f0dba42.cmd |

| c_27803.nls | c_12058.nls |

The brute-forced DLL names of Careto2 plugins also turned out to resemble the names of plugins used by The Mask in 2007–2013:

| 2007-2013 attack module names | 2019 attack module names |

| FileFlt | FileFilter |

| Storage | Storage |

| Config | ConfigMgr |

Finally, the campaigns conducted in 2007–2013 and 2019 have multiple overlaps in terms of TTPs, for instance the use of virtual file systems for storing plugins and leveraging of COM hijacking for persistence.

Regarding the attacks observed in 2022 and 2024, we have also attributed these to The Mask, mainly for the following reasons:

- The organization in Latin America, infected in 2022, was the one compromised by Careto2 in 2019, and by historical The Mask implants in 2007-2013

- In both 2019 and 2022 cases, the same unique file name was used to deploy implants to infected machines: ~dfae01202c5f0dba42.cmd;

- The attacks from 2019 and 2022–2024 overlap in terms of TTPs, as the malware deployed in these attacks uses cloud storages for exfiltration and propagates across system processes.

Conclusion

Ten years after we last saw Careto cyberattacks, this actor is still as powerful as before. That is because Careto is capable of inventing extraordinary infection techniques, such as persistence through the MDaemon email server or implant loading though the HitmanPro Alert driver, as well as developing complex multi-component malware. While we cannot estimate how long it will take for the community to discover the next attacks by this actor, we are confident that their next campaign will be as sophisticated as the previous ones.

If you want more technical information about Careto, please feel free to also read the research paper on this actor, published in Proceedings of the 34th Virus Bulletin International Conference.

Careto is back: what’s new after 10 years of silence?