Anyone who has ever analyzed malware designed to steal data from online banking customers will agree that Brazil is one of the biggest sources of so-called banking Trojans. But why exactly is Brazil a world leader in producing this type of malicious program? Who is responsible and what drives them? Having analyzed the malicious code originating from Brazil, we are ready to share our conclusions.

Why Brazil?

Brazil is the biggest country in Latin America with a population of approximately 200 million people. Nearly one third of the population – about 70 million – are Internet users and their number is constantly growing.

Brazil’s highly stratified social structure often means that those on a low income are drawn into illegal activity, including writing malicious programs designed to steal data belonging to bank customers. The fact that online banking systems are widely used in Brazil makes this type of criminal activity all the more attractive. Additionally, the country does not have legislation which effectively combats cybercrime.

Between them, Brazil’s biggest banks have millions of online banking customers. For instance, Banco do Brasil has 7.9 million online customers, Bradesco has 6.9 million, Itaú has 4.2 million and Caixa has 3.69 million. These numbers are high enough to motivate the criminals: even if the percentage of successful attacks is small, the profits can still be impressive.

Targets

Unfortunately, lots of customers at different banks fall victim to this type of cybercrime.

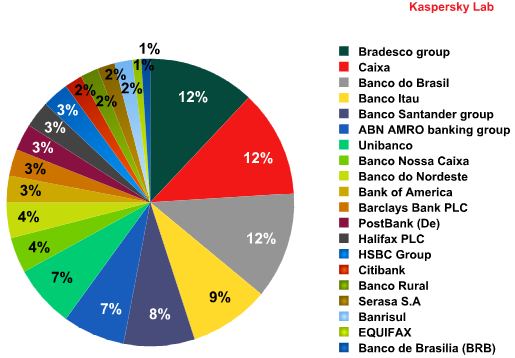

Percentage of malicious programs designed to steal customer data from different banks

The pie chart shows that the majority of malicious programs that steal money from bank accounts target customers of Bradesco, Caixa, Banco do Brasil and Itaú. This is hardly surprising considering they are Brazil’s largest banks and provide services to millions of people.

As well as customer numbers, cybercriminals are interested in the security measures that the banks employ. So, what do the banks do to secure the transactions made by their customers?

Many banks suggest that their online banking customers install a special plug-in – G-Buster – on their computers before they access the online banking system. The G-Buster plug-in is designed to prevent any malicious code from running during the authorization or transaction process. This mechanism is the only security measure used by Caixa and Banco do Brasil to protect their customers. Unfortunately, as we shall see later, the presence of the G-Buster plug-in on a computer does not guarantee secure online banking.

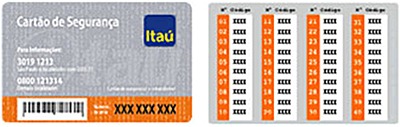

Other banks, e.g. Itaú, provide their customers with other security tools in addition to the plug-in, such as tokens or security cards.

Security card issued by Itaú

Bradesco bank offers its customers yet another method of protection that entails a pair of unique digital keys (certificates) being generated for each customer. One of the keys is stored on the customer’s computer while it is recommended that the second be stored on a removable storage device. When a user tries to connect to the bank’s site, the system requires the path to the second certificate. In order to gain access, the customer has to insert the removable storage device (e.g. a flash drive) with the second certificate into the computer.

In theory, these mechanisms ought to be sufficient to protect users. As we shall see in practice, however, they are not very effective. Either they fail to fully protect online banking customers or the cost puts people off. For example, if a bank customer wants to use a token, he first has to buy it. This deters lots of customers from using tokens, leaving them vulnerable to attack by cybercriminals.

Which cybercriminal methods are used to cause the most effective mass infection of users’ computers?

Infected sites

Malicious programs more often than not spread via websites. In order to spread their malicious programs, criminals either compromise legitimate sites located on domains around the world, or use temporary or free hosting. Interestingly, the domains of the Russian company RBC Media – nm.ru and pochta.ru – are often used as free hosting for spreading malicious programs.

In some cases when cybercriminals plan a particularly serious project they need a long-term resource. For this particular purpose they use “bulletproof” hosting, with the use of technology that identifies the IP addresses of potential victims. Knowing the IP address of a user that has ended up on an infected web page enables criminals to perform targeted attacks and hide malicious programs from antivirus companies. IT security specialists and those not residing in Latin America have no access to the binary malicious code. In most cases they will be offered photos of Brazilian girls.

How then do online banking customers end up on the infected pages? They are lured to these sites with the help of spam messages that make use of classic social engineering tactics. Sometimes these messages imitate emails sent by the bank, or offer snippets of news and gossip about the country’s celebrities. Of course, adult content spam is also used. The links in these spam messages lead users to infected sites.

Attacks – Brazilian style

Brazilian banking Trojans are never spread as separate files. The infection process always involves the installation of a whole range of additional malicious programs on a victim’s computer.

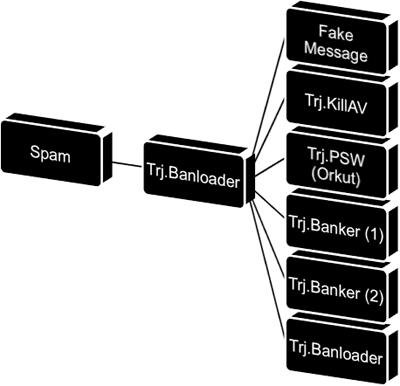

Cybercriminals do not focus solely on banking information; they conduct complex attacks. The classic infection scheme looks like this:

Classic scheme used to infect computers of online banking customers

Initially, there is one Trojan on the server whose task it is to download and install all the other malicious programs on a user’s computer:

- a program that steals account data to social networking sites;

- a program that combats antivirus solutions;

- one or two programs that monitor activity when users connect to banking sites, intercept session data, and send harvested data such as passwords and user names to the cybercriminals.

Social networking sites

Social networking sites have become an important source of almost any type of data about a user. A person’s full name, date of birth, address, social status, etc., can be used by criminals, for example, to make an “official” enquiry to a bank’s call center about a user’s PIN code.

The most popular social networking site in Brazil is Orkut. It has nearly 23 million users worldwide, 54% of which are Brazilians. The users of this social networking site are most often attacked by Brazilian cybercriminals.

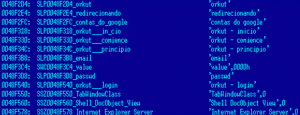

Fragment of code designed to steal passwords from Orkut users

As a rule, personal data and passwords to social networking sites are sent to the cybercriminals’ email account.

Combating antivirus solutions

How do cybercriminals combat antivirus solutions installed on computers and the G-Buster plug-in?

This plug-in is supposed to ensure that transactions made by the customers of a number of banks are secure. In order to prevent G-Buster from being removed by a malicious program, its manufacturers used rootkit technology to deploy G-Buster deep into the system. However, cybercriminals make use of perfectly legitimate programs that are designed to counteract rootkits.

The most popular anti-rootkit program is Avenger. When infecting a computer a Trojan downloader loads this utility in the system along with a list of files that need to be removed (instructions). All a cybercriminal needs to do to effectively remove the plug-in is to launch the utility and reboot the system.

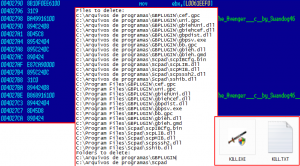

Example of the instructions used to remove the G-Buster plug-in using the legitimate Avenger anti-rootkit utility

The utility’s only parameter is the path to the files that need be removed. The screenshot above shows a case where the G-Buster plug-in can only be removed from a system installed in the Portuguese or English.

After the system is rebooted, the original plug-in is removed completely and in some cases another plug-in containing malicious code is installed. The new plug-in enables a user to access their bank account, but also steals account data and forwards it to the cybercriminals.

Exactly the same approach is used to remove antivirus programs from a user’s system.

Data theft

After an online transaction is performed by a user, the banking Trojan downloaded on the computer captures data that makes it possible to access the victim’s account. The account details are then forwarded to the cybercriminals’ email address, or to an FTP server or remote database server.

Fragment of code responsible for forwarding stolen data to a remote database server

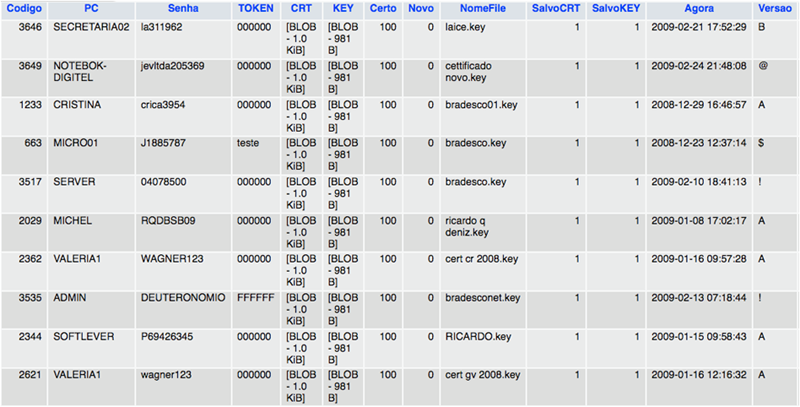

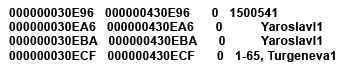

Extract from a database (user accounts stolen by cybercriminals)

Extract from Bradesco Bank’s database (customer data stolen by cybercriminals)

The screenshots above are of real databases and contain customer data such as user names, passwords, security certificates, etc.

Activity by cybercriminals is not limited to stealing bank accounts details and data for accessing social networking sites, however. They regularly attempt to obtain the MAC address of a user’s network card, the IP address, computer name and other information that can be used to connect to a bank. They do this to cover their tracks and implicate the victim as much as possible – if the bank initiates an investigation, the logs will make everything look as if it was the client who withdrew money or transferred it to another account.

Cybercriminals are also interested in any email addresses used on an infected computer and the passwords used to access them. Often, these addresses and passwords are used by users to access their accounts on social networking sites. And, as I have already mentioned, this presents some attractive opportunities to commit more crimes. In addition, these addresses may be registered in a bank’s database as the official customer contact address, making them trusted addresses. Just imagine what cybercriminals can do when they have access to these addresses!

In order to steal email passwords, cybercriminals also use legitimate programs that can restore forgotten passwords. Such programs are capable of reading passwords stored in the most popular mail clients such as Microsoft Outlook, Microsoft Outlook Express, etc.

Stolen email addresses and passwords are sent to remote web servers.

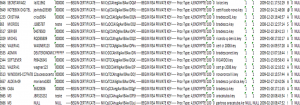

Fragment of code which shows how stolen addresses are sent to a remote web server

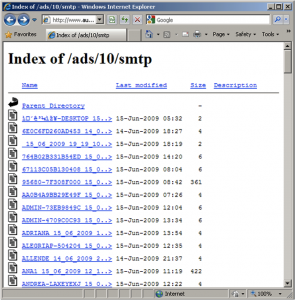

Data stolen by cybercriminals is stored on a web sever

Profile of a cybercriminal

Once cybercriminals have stolen personal data and gained access to a customer’s bank account, they generally employ money mules; the first transaction will be made from the victim’s account to a money mule account. The mules in their turn transfer the money to a third account in return for a commission. However, if only a small sum has been stolen, the money will generally be directly transmitted to the cybercriminals’ account.

In order to understand who is behind these crimes, the following facts need to be analyzed:

- nearly all samples of banking Trojans are written in Delphi;

- some samples are infected with the viruses Virut or Induc;

- in some cases, cybercriminals compromise legal web pages to distribute malicious programs.

Analysis showed that Delphi is not included in the curriculums of Brazilian universities. This programming language can only be learnt at special programming courses or at a vocational college. This suggests that the cybercriminals are not necessarily people with a higher education and that they may be fairly young.

The fact that samples are infected with viruses such as Virut suggests that the cybercriminals’ computers are also infected. Very often the sources of these infections are sites containing cracks for software, sites with serial numbers for programs, porn sites and P2P networks. Most probably these kinds of sites and programs are popular with cybercriminals. In Brazil, these sites are mostly visited by young people, which would lend evidence to the claim that the cybercriminals are young – though piracy could be committed by people of various ages.

The fact that cybercriminals often compromise legitimate websites points to teamwork. Every team member has his own specialization – hacking, writing malicious code, etc.

So, our assumption is that the cyberattacks on customers of Brazilian banks are organized by groups of cybercriminals who are generally young and come from poor families. Their desire to make a quick profit shapes their lives, which consists of writing malicious code, infecting users, stealing money, spending it and then repeating the whole process over again. They find themselves in a vicious circle that is very difficult to break out of.

A recent investigation launched by the Brazilian police force, which ended in the arrest of the culprits, confirmed our supposition. Below are some photos of the criminals.

Photographs of cybercriminals (Brazilian police archive photos)

It would seem we have presented a more or less accurate portrait of these cybercriminals. But, as is often the case, things are not so straightforward.

Hint of Russia

Typical Brazilian banking Trojans have a number of characteristics – huge file size, Portuguese strings in the code, etc. From time to time, however, there are some samples that stand out.

At first glance, these banking Trojans don’t seem to differ from the classic examples – the same banks are attacked, the names of the files may coincide with the names used by Brazilian cybercriminals. However, a closer look reveals some clear distinctions:

- the size of the file is optimized;

- the language of the operating system used for compilation is not Portuguese;

- stolen data is transferred via secure channels.

So who is behind these banking Trojans? Brazilian cybercriminals who have just graduated from university? It’s very unlikely.

First of all, when removing a bank’s security plug-in these cybercriminals use an anti-rootkit called Partizan instead of the classic Avenger. The former is part of the Russian edition of the UnHackMe program.

Secondly, there is absolutely no Portuguese in the code.

And finally, after analyzing the secure data transfer channel, we discovered some interesting registration information:

Registration data of a connection used to transfer stolen bank details

Who is organizing these attacks? On the face of it, they are Brazilian malware writers. And if a criminal investigation is launched, the criminals will be sought in Brazil. But, when you consider the registration data and some other details (e.g. the programming language, file size and the strings in the code), it turns out that Russian cybercriminals are stealing money from Brazilian banks.

Conclusion

Brazil’s law enforcement agencies are working hard to track down the cybercriminals. Why, then, does the number of malicious programs continue to grow every day?

The problem of cybercrime is exacerbated by the fact that banks wish to avoid public investigation of such thefts. In order to protect their reputation, banks prefer to compensate customers for losses incurred by infection with malicious code, and simply recommend that the affected customer reconfigures his computer by reinstalling the operating system.

In addition, the cybercrime departments in different Brazilian states experience difficulty in exchanging data with each other. However, this problem is not exclusive to Brazil and affects many other countries.

Additionally, online banking customers’ limited awareness of IT security issues can cause them to fall into the hands of cybercriminals.

There is no reason to expect the Internet will become safer while these problems (a low level of IT security awareness, the banks’ policies, social conditions, and a lack of effective legislative tools) continue to exist. Perhaps Brazilian banks should invest more heavily in security solutions which will offer their customers reliable protection, including distributing tokens or other security devices free of charge. This would reduce the likelihood of cybertheft, and correspondingly reduce overall losses.

It is obvious that IT security companies, law enforcement agencies and governmental bodies around the world need to work on interacting more effectively with each other. Until this happens, there can be no significant reduction in the amount of cybercrime.

“Brazil: a country rich in banking Trojans”