The past few days has seen an extensive discussion within the IT security industry about a cyberespionage campaign called Turla, aka Snake and Uroburos, which, according to G-DATA experts, may have been created by Russian special services.

One of the main conclusions also pointed out by research from BAE SYSTEMS, is a connection between the authors of Turla and those of another malicious program, known as Agent.BTZ, which infected the local networks of US military operations in the Middle East in 2008.

We first became aware of this targeted campaign in March 2013. This became apparent when we investigated an incident which involved a highly sophisticated rootkit. We called it the ‘Sun rootkit’, based on a filename used as a virtual file system: sunstore.dmp, also accessible as \.Sundrive1 and \.Sundrive2. The ‘Sun rootkit’ and Uroburos are the same.

We are still actively investigating Turla, and we believe it is far more complex and versatile than the already published materials suggest.

At this point, I would like to discuss the connection between Turla and Agent.btz in a little more detail.

Agent.btz: a global epidemic or a targeted attack?

The story of Agent.btz began back in 2007 and was extensively covered by the mass media in late 2008 when it was used to infect US military networks.

Here is what Wikipedia has to say about it: “The 2008 cyberattack on the United States was the ‘worst breach of U.S. military computers in history’. The defense against the attack was named ‘Operation Buckshot Yankee’. It led to the creation of the United States Cyber Command.

It started when a USB flash drive infected by a foreign intelligence agency was left in the parking lot of a Department of Defense facility at a base in the Middle East. It contained malicious code and was put into a USB port from a laptop computer that was attached to United States Central Command.

The Pentagon spent nearly 14 months cleaning the worm, named Agent.btz, from military networks. Agent.btz, a variant of the SillyFDC worm, has the ability ‘to scan computers for data, open backdoors, and send through those backdoors to a remote command and control server’.”

We do not know how accurate is the story with the USB flash drive left in the parking lot. We have also heard a number of other versions of this story, which may, or may not be right. However, the important fact here is that Agent.btz was a self replicating computer worm, not just a Trojan. Another important fact is that the malware has dozens of different variants.

We believe that the initial variants of the worm were created back in 2007. By 2011 a large number of its modifications had been detected. Today, most variants are detected by Kaspersky products as Worm.Win32.Orbina.

Curiously, in accordance with the naming convention used by PC Tools, the worm is also named Voronezh.1600 (http://www.threatexpert.com/report.aspx?md5=02eda1effde92bdf8462abcf40c4f776) – possibly a reference to the mythical Voronezh school of hackers, in Russia.

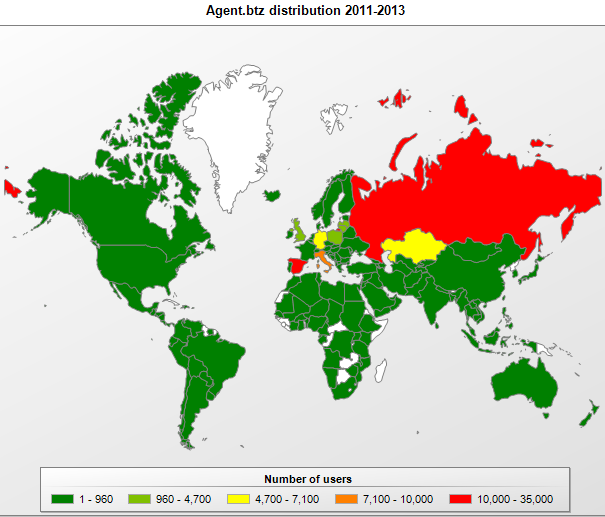

In any event, it is quite obvious that the US military were not the only victims of the worm. Copying itself from one USB flash drive to another, it rapidly spread globally. Although no new variants of the malware have been created for several years and the vulnerability enabling the worm to launch from USB flash drives using “autorun.inf” have long since been closed in newer versions of Windows, according to our data Agent.btz was detected 13,832 times in 107 countries across the globe in 2013 alone!

The dynamics of the worm’s epidemic are also worth noting. Over three years – from 2011 to 2013 – the number of infections caused by Agent.btz steadily declined; however, the top 10 affected countries changed very little.

| Agent.BTZ detections (unique users) | 2011 | |

| 1 | Russian Federation | 24111 |

| 2 | Spain | 9423 |

| 3 | Italy | 5560 |

| 4 | Kazakhstan | 4412 |

| 5 | Germany | 3186 |

| 6 | Poland | 3068 |

| 7 | Latvia | 2805 |

| 8 | Lithuania | 2016 |

| 9 | United Kingdom | 761 |

| 10 | Ukraine | 629 |

| Total countries | 147 | |

| Total users | 63021 |

| Agent.BTZ detections (unique users) | 2012 | |

| 1 | Russian Federation | 11211 |

| 2 | Spain | 5195 |

| 3 | Italy | 3052 |

| 4 | Germany | 2185 |

| 5 | Kazakhstan | 1929 |

| 6 | Poland | 1664 |

| 7 | Latvia | 1282 |

| 8 | Lithuania | 861 |

| 9 | United Kingdom | 335 |

| 10 | Ukraine | 263 |

| Total countries | 130 | |

| Total users | 30923 |

| Agent.BTZ detections (unique users) | 2013 | |

| 1 | Russian Federation | 4566 |

| 2 | Spain | 2687 |

| 3 | Germany | 1261 |

| 4 | Italy | 1067 |

| 5 | Kazakhstan | 868 |

| 6 | Poland | 752 |

| 7 | Latvia | 562 |

| 8 | Lithuania | 458 |

| 9 | Portugal | 157 |

| 10 | United Kingdom | 123 |

| Total countries | 107 | |

| Total users | 13832 |

The statistics presented above are based on the following Kaspersky Anti-Virus verdicts: Worm.Win32.Autorun.j, Worm.Win32.Autorun.bsu, Worm.Win32.Autorun.bve, Trojan-Downloader.Win32.Agent.sxi, Worm.Win32.AutoRun.lqb, Trojan.Win32.Agent.bve, Worm.Win32.Orbina

To summarize the above, the Agent.btz worm has clearly spread all over the world, with Russia leading in terms of the number of infections for several years.

Map of infections caused by different modifications of “Agent.btz” in 2011-2013

For detailed information on the modus operandi of Agent.btz, I recommend reading an excellent report prepared by Sergey Shevchenko from ThreatExpert, back in November 2008.

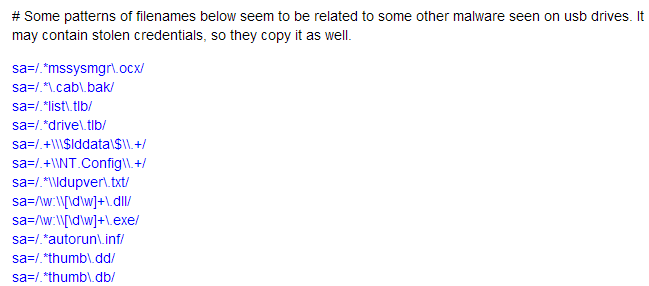

On infected systems, the worm creates a file named ‘thumb.dd’ on all USB flash drives connected to the computer, using it to store a CAB file containing the following files: “winview.ocx”, “wmcache.nld” and “mswmpdat.tlb”. These files contain information about the infected system and the worm’s activity logs for that system. Essentially, “thumb.dd” is a container for data which is saved on the flash drive, unless it can be sent directly over the Internet to the C&C server.

If such a flash drive is inserted into another computer infected with Orbina, the file “thumb.dd” will be copied to the computer under the name “mssysmgr.ocx”.

Given this functionality and the global scale of the epidemic caused by the worm, we believe that there are tens of thousands of USB flash drives in the world containing files named “thumb.dd” created by Agent.btz at some point in time and containing information about systems infected by the worm.

Red October: a data collector?

Over one year ago, we analyzed dozens of modules used by Red October, an extremely sophisticated cyber espionage operation. While performing the analysis, we noticed that the list of files that a module named “USB Stealer” searches for on USB flash drives connected to infected computers included the names of files created by Agent.btz “mssysmgr.ocx” and “thumb.dd”.

This means that Red October developers were actively looking for data collected several years previously by Agent.btz. All the USB Stealer modules known to us were created in 2010-2011.

Both Red October and Agent.btz were, in all probability, created by Russian-speaking malware writers. One program “knew” about the files created by the other and tried to make use of them. Are these facts sufficient to conclude that there was a direct connection between the developers of the two malicious programs?

I believe they are not.

First and foremost, it should be noted that the fact that the file “thumb.dd” contains data from Agent.btz-infected systems was publicly known. It is not impossible that the developers of Red October, who must have been aware of the large number of infections caused by Agent.btz and of the fact that the worm had infected US military networks, simply tried to take advantage of other people’s work to collect additional data. It should also be remembered that Red October was a tool for highly targeted pinpoint attacks, whereas Agent.btz was a worm, by definition designed to spread uncontrollably and “collect” any data it could access.

Basically, any malware writer could add scanning of USB flash drives for “thumb.dd” files and the theft of those files to their Trojan functionality. Why not steal additional data without too much additional effort? However, decrypting the data stolen requires one other thing – the encryption key.

Agent.btz and Turla/Uroburos

The connection between Turla and Agent.btz is more direct, although not sufficiently so to conclude that the two programs have the same origin.

Turla uses the same file names as Agent.btz – “mswmpdat.tlb”, “winview.ocx” and “wmcache.nld” for its log files stored on infected systems.

All the overlapping file names are presented in the table below:

| Agent.btz | Red October | Turla | |

| Log files | thumb.dd | thumb.dd | |

| winview.ocx | winview.ocx | ||

| mssysmgr.ocx | mssysmgr.ocx | ||

| wmcache.nld | wmcache.nld | ||

| mswmpdat.tlb | mswmpdat.tlb | ||

| fa.tmp | fa.tmp |

In addition, Agent.btz and Turla use the same XOR key to encrypt their log files:

as80cbLnmz54cs5Ldn4ri3do5L6gs923HL34x2f5cvd0fk6c1a0s

The key is not a secret, either: it was discovered and published back in 2008 and anybody who had an interest in the Agent.btz story knew about the key. Is it possible that the developers of Turla decided to use somebody else’s key to encrypt their logs? We are as yet unable to determine at what point in time this particular key was adopted for Turla. It is present in the latest samples (dated 2013-2014), but according to some data the development of Turla began back in 2006 – before the earliest known variant of Agent.btz was created.

Red October and Turla

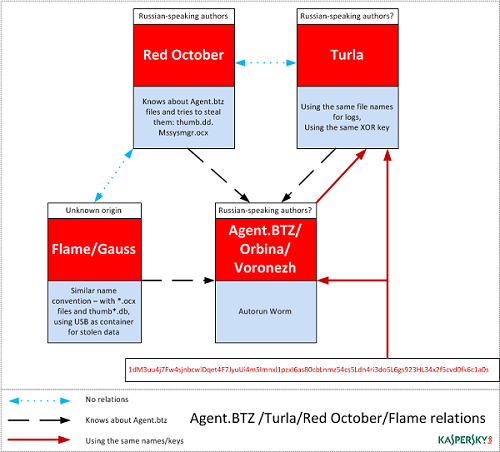

Now we have determined that Red October “knew” about the file names used by Agent.btz and searched for them. We have also determined that Turla used the same file names and encryption key as Agent.btz.

So what about a possible connection between Red October and Turla? Is there one? Having analyzed all the data at our disposal, we do not see any overlapping between the two projects. They do not “know” about each other, they do not communicate between themselves in any way, they are different in terms of their architecture and the technologies used.

The only thing they really have in common is that the developers of both Rocra and Turla appear to have Russian as their native language.<?

What about Flame?

Back in 2012, while analyzing Flame and its cousins Gauss and MiniFlame, we noticed some similarities between them and Agent.btz (Orbina). The first thing we noticed was the analogous naming convention applied, with a predominance of use of files with the .ocx extension. Let’s take as an example the name of the main module of Flame – “mssecmgr.ocx”. In Agent.btz a very similar name was used for the log-file container on the infected system – “mssysmgr.ocx”. And in Gauss all modules were in the form of files with names *.ocx.

| Feature | Flame | Gauss |

|---|---|---|

| Encryption methods | XOR | XOR |

| Using USB as storage | Yes (hub001.dat) | Yes (.thumbs.db) |

The Kurt/Godel module in Gauss contains the following functionality: when a drive contains a ‘.thumbs.db’ file, its contents are read and checked for the magic number 0xEB397F2B. If found, the module creates %commonprogramfiles%systemwabdat.dat and writes the data to this file, and then deletes the ‘.thumbs.db’ file.

This is a container for data stolen by the ‘dskapi’ payload.

Besides, MiniFlame (module icsvnt32) also ‘knew’ about the ‘.thumbs.db’ file, and conducted a search for it on USB sticks.

If we recall how our data indicate that the development of both Flame and Gauss started back in 2008, it can’t be ruled out that the developers of these programs were well acquainted with the analysis of Agent.btz and possibly used some ideas taken from it in their development activities.

All together now

The data can be presented in the form of a diagram showing the interrelations among all the analyzed malicious programs:

As can be seen in the diagram, the developers of all three (even four, if we include Gauss) spy programs knew about Agent.btz, i.e., about how it works and what filenames it uses, and used that information either to directly adopt the functionality, ideas and even filename, or attempted to use the results of the work of Agent.btz.

Summarizing all the above, it is possible to regard Agent.btz as a certain starting point in the chain of creation of several different cyber-espionage projects. The well-publicized story of how US military networks were infected could have served as the model for new espionage programs having similar objectives, while its technologies were clearly studied in great detail by all interested parties. Were the people behind all these programs all the same? It’s possible, but the facts can’t prove it.

Agent.btz: a Source of Inspiration?