In February 2017 an article in the Polish media broke the silence on a long-running story about attacks on banks, allegedly related to the notoriously known Lazarus Group. While the original article didn’t mention Lazarus Group it was quickly picked up by security researchers. Today we’d like to share some of our findings, and add something new to what’s currently common knowledge about Lazarus Group activities, and their connection to the much talked about February 2016 incident, when an unknown attacker attempted to steal up to $851M USD from Bangladesh Central Bank.

Since the Bangladesh incident there have been just a few articles explaining the connection between Lazarus Group and the Bangladesh bank heist. One such publication was made available by BAE systems in May 2016, however it only included analysis of the wiper code. This was followed by another blogpost by Anomali Labs, confirming the same wiping code similarity. This similarity was found to be satisfying to many readers, however at Kaspersky Lab, we were looking for a stronger connection.

Other claims that Lazarus was the group behind attacks on the Polish financial sector, came from Symantec in 2017, which noticed string reuse in malware at one of their Polish customers. Symantec also confirmed seeing the Lazarus wiper tool in Poland at one of their customers. However, from this it’s only clear that Lazarus might have attacked Polish banks.

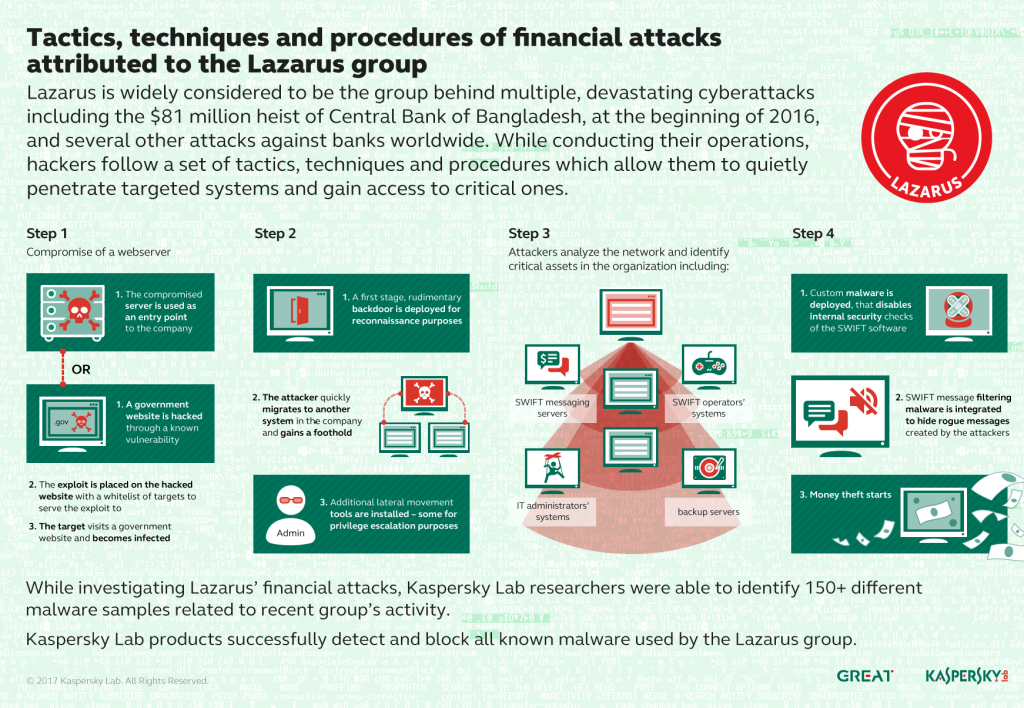

While all these facts are fascinating, the connection between Lazarus attacks on banks, and their role in attacks on banks’ systems, was still loose. The only case where specific malware targeting the bank’s infrastructure used to connect to SWIFT messaging server was discovered, is the Bangladesh Central Bank case. However, while almost everybody in the security industry has heard about the attack, few technical details have been revealed to the public based on the investigation that took place on site at the attacked company. Considering that the afterhack publications by the media mentioned that the investigation stumbled upon three different attackers, it was not obvious whether Lazarus was the one responsible for the fraudulent SWIFT transactions, or if Lazarus had in fact developed its own malware to attack banks’ systems.

We would like to add some strong facts that link some attacks on banks to Lazarus, and share some of our own findings as well as shed some light on the recent TTPs used by the attacker, including some yet unpublished details from the attack in Europe in 2017.

This is the first time we announce some Lazarus Group operations that have thus far gone unreported to the public. We have had the privilege of investigating these attacks and helping with incident response at a number of financial institutions in South East Asia and Europe. With cooperation and support from our research partners, we have managed to address many important questions about the mystery of Lazarus attacks, such as their infiltration method, their relation to attacks on SWIFT software and, most importantly, shed some light on attribution.

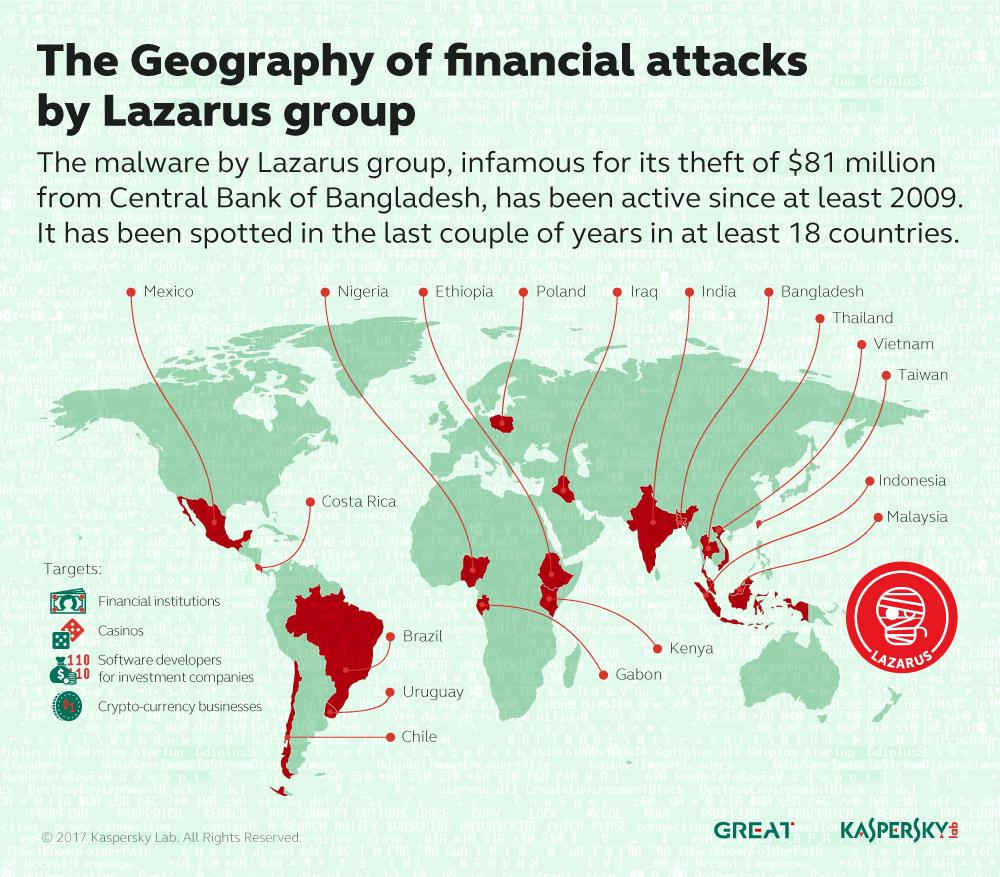

Lazarus attacks are not a local problem and clearly the group’s operations span across the whole world. We have seen the detection of their infiltration tools in multiple countries in the past year. Lazarus was previously known to conduct cyberespionage and cybersabotage activities, such as attacks on Sony Pictures Entertainment with volumes of internal data leaked, and many system harddrives in the company wiped. Their interest in financial gain is relatively new, considering the age of the group, and it seems that they have a different set of people working on the problems of invisible money theft or the generation of illegal profit. We believe that Lazarus Group is very large and works mainly on infiltration and espionage operations, while a substantially smaller units within the group, which we have dubbed Bluenoroff, is responsible for financial profit.

The watering hole attack on Polish banks was very well covered by media, however not everyone knows that it was one of many. Lazarus managed to inject malicious code in many other locations. We believe they started this watering hole campaign at the end of 2016 after their other operation was interrupted in South East Asia. Lazarus/Bluenoroff regrouped and rushed into new countries, selecting mostly poorer and less developed locations, hitting smaller banks because they are, apparently, easy prey.

To date, we’ve seen Bluenoroff attack four main types of targets:

- Financial institutions

- Casinos

- Companies involved in the development of financial trade software

- Crypto-currency businesses

Here is the full list of countries where we have seen Bluenoroff watering hole attacks:

- Mexico

- Australia

- Uruguay

- Russian Federation

- Norway

- India

- Nigeria

- Peru

- Poland

Of course, not all attacks were as successful as the Polish attack case, mainly because in Poland they managed to compromise a government website. This website was frequently accessed by many financial institutions making it a very powerful attack vector. Nevertheless, this wave of attacks resulted in multiple infections across the world, adding new hits to the map we’ve been building.

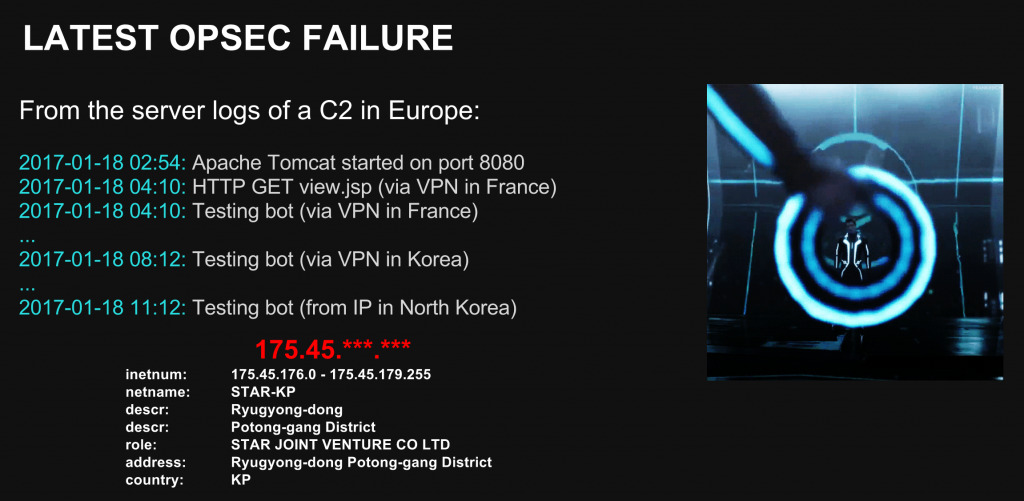

One of the most interesting discoveries about Lazarus/Bluenoroff came from one of our research partners who completed a forensic analysis of a C2 server in Europe used by the group. Based on the forensic analysis report, the attacker connected to the server via Terminal Services and manually installed an Apache Tomcat server using a local browser, configured it with Java Server Pages and uploaded the JSP script for C2. Once the server was ready, the attacker started testing it. First with a browser, then by running test instances of their backdoor. The operator used multiple IPs: from France to Korea, connecting via proxies and VPN servers. However, one short connection was made from a very unusual IP range, which originates in North Korea.

In addition, the operator installed an off-the-shelf cryptocurrency mining software that should generate Monero cryptocoins. The software so intensely consumed system resources that the system became unresponsive and froze. This could be the reason why it was not properly cleaned, and the server logs were preserved.

This is the first time we have seen a direct link between Bluenoroff and North Korea. Their activity spans from backdoors to watering hole attacks, and attacks on SWIFT servers in banks of South East Asia and Bangladesh Central Bank. Now, is it North Korea behind all the Bluenoroff attacks after all? As researchers, we prefer to provide facts rather than speculations. Still, seeing IP in the C2 log, does make North Korea a key part of the Lazarus Bluenoroff equation.

Conclusions

Lazarus is not just another APT actor. The scale of the Lazarus operations is shocking. It has been on a spike since 2011 and activities didn’t disappear after Novetta published the results of its Operation Blockbuster research, in which we also participated. All those hundreds of samples that were collected give the impression that Lazarus is operating a factory of malware, which produces new samples via multiple independent conveyors.

We have seen them using various code obfuscation techniques, rewriting their own algorithms, applying commercial software protectors, and using their own and underground packers. Lazarus knows the value of quality code, which is why we normally see rudimentary backdoors being pushed during the first stage of infection. Burning those doesn’t impact the group too much. However, if the first stage backdoor reports an interesting infection they start deploying more advanced code, carefully protecting it from accidental detection on disk. The code is wrapped into a DLL loader or stored in an encrypted container, or maybe hidden in a binary encrypted registry value. It usually comes with an installer that only attackers can use, because they password protect it. It guarantees that automated systems – be it a public sandbox or a researcher’s environment – will never see the real payload.

Most of the tools are designed to be disposable material that will be replaced with a new generation as soon as they are burnt. And then there will be newer, and newer, and newer versions. Lazarus avoids reusing the same tools, same code, and the same algorithms. “Keep morphing!” seems to be their internal motto. Those rare cases when they are caught with same tools are operational mistakes, because the group seems to be so large that one part doesn’t always know what the other is doing.

This level of sophistication is something that is not generally found in the cybercriminal world. It’s something that requires strict organisation and control at all stages of operation. That’s why we think that Lazarus is not just another APT actor.

Of course such processes require a lot of money to keep running, which is why the appearance of the Bluenoroff subgroup within Lazarus was logical.

Bluenoroff, being a subgroup of Lazarus, is focusing on financial attacks only. This subgroup has reverse engineering skills because they spend time tearing apart legitimate software, and implementing patches for SWIFT Alliance software, in attempts to find ways to steal big money. Their malware is different and they aren’t exactly soldiers that hit and run. Instead, they prefer to make an execution trace to reconstruct and quickly debug the problem. They are field engineers that come when the ground is already cleared after conquering new lands.

One of Bluenoroff’s favorite strategies is to silently integrate into running processes without breaking them. From the code we’ve seen, it looks as if they are not exactly looking for a hit and run solution when it comes to money theft. Their solutions are aimed at invisible theft without leaving a trace. Of course, attempts to move around millions of USD can hardly remain unnoticed, but we believe that their malware might be secretly deployed now in many other places and it isn’t triggering any serious alarms because it’s much more quiet.

We would like to note, that in all of the observed attacks against banks that we have analyzed, SWIFT software solutions running on banks’ servers haven’t demonstrated or exposed any specific vulnerability. The attacks were focused on banking infrastructure and staff, exploiting vulnerabilities in commonly used software or websites, bruteforcing passwords, using keyloggers and elevating privileges. However, the way banks use servers with SWIFT software installed requires personnel responsible for the administration and operation. Sooner or later, the attackers find these personnel, gain the necessary privileges, and access the server connected to the SWIFT messaging platform. With administrative access to the platform they can manipulate software running on the system as they wish. There is not much that can stop them, because from a technical perspective, their activities may not differ from what an authorized and qualified engineer would do: starting and stopping services, patching software, modifying the database. Therefore, in all the breaches we have analyzed, SWIFT, as an organization has not been at direct fault. More than that, we have witnessed SWIFT trying to protect its customers by implementing the detection of database and software integrity issues. We believe that this is a step in the right direction and these activities should be extended with full support. Complicating the patches of integrity checks further may create a serious threat to the success of future operations run by Lazarus/Bluenoroff against banks worldwide.

To date, the Lazarus/Bluenoroff group has been one of the most successful in launching large scale operations against the financial industry. We believe that they will remain one of the biggest threats to the banking sector, finance and trading companies, as well as casinos for the next few years. We would like to note that none of the financial institutions we helped with incident response and investigation reported any financial loss.

As usual, defense against attacks such as those from Lazarus/Bluenoroff should include a multi-layered approach. Kaspersky products include special mitigation strategies against this group, as well as the many other APT groups we track. If you are interested in reading more about effective mitigation strategies in general, we recommend the following articles:

We will continue tracking the Lazarus/Bluenoroff actor and share new findings with our intel report subscribers, as well as with the general public. If you would like to be the first to hear our news, we suggest you subscribe to our intel reports.

For more information, contact: intelreports@kaspersky.com.

Lazarus Under The Hood