Today Kaspersky Lab’s team of experts published a detailed research report that analyzes a sustained cyberespionage campaign conducted by the cybercriminal organization known as Winnti.

According to report, the Winnti group has been attacking companies in the online video game industry since 2009 and is currently still active.

The group’s objectives are stealing digital certificates signed by legitimate software vendors in addition to intellectual property theft, including the source code of online game projects.

The attackers’ favorite tool is the malicious program we called “Winnti”. It has evolved since its first use, but all variants can be divided into two generations: 1.x and 2.x. Our publication describes both variants of this tool.In our report we publish an analysis of the first generation of Winnti.

The second generation (2.x) was used in one of the attacks which we investigated during its active stage, helping the victim to interrupt data transfer and isolate infections in the corporate network. The incidents, as well as results of our investigation, are described in the full report (PDF) on the Winnti group.

The Executive Summary is available here.

Is this research about a gaming Trojan from 2011? Why do you think it is significant?

This research is about a set of industrial cyberespionage campaigns and a criminal organization which massively penetrates many software companies and plays a very important role in the success of cyberespionage campaigns of other malicious actors.

It is important to be aware of this threat actor to understand the broader picture of cyberattacks coming from Asia. Having infected gaming companies that do business in the MMORPG space, the attackers potentially get access to millions of users. So far, we don’t have data that the attackers stole from common users but we do have at least 2 incidents where the Winnti malware was planted on an online game update servers and these malicious executables were spread among a large number of the online gamers. The samples we observed seemed not to be malware targeting end user gamers, but a malware module which accidentally got into wrong place. Hoever, the potential for attackers to misuse such access to infect hundreds of millions of Internet users creates a major global risk.

It’s important to understand that many gaming companies do business not only in gaming, but very often they are also developers or publishers of different other types of software. We have tracked an incident where a compromised company served an update of their software which included a Trojan from the Winnti hacking team. That became an infection vector to penetrate another company, which in turn led to a personal data leak of large number of its customers.

So far, this research is dedicated to a malicious group that not only undermines trust in fair gameplay but has a serious impact on trust in software vendors in general, especially in the regions where the Winnti group is active at the moment.

What are the malicious purposes of this Trojan?

The Trojan, or to be precise, a penetration kit called Winnti includes various modules to provide general purpose remote access to compromised machines. This includes general system information collection, file and process management, creating chains of network port redirection for convenient data exfiltration and remote desktop access.

Is this attack still active?

Yes, despite active steps to stop the attackers by the revocation of digital certificates, detection of the malware and an active investigation, the attackers remain active, with at least several victim companies around the world being actively compromised.

What is the potential impact for common users?

The malware in question does not target common users at the moment. With the use of that malware, the attackers are targeting online game software developer companies. So far we have not discovered malware with marks of Winnti team origin that targets common users but it is not improbable that such malware exists.

What is the possible damage for gaming companies?

The malware has been known to steal digital certificates used by gaming companies, which allows the attackers to distribute malicious software signed by trusted entities. Also, we’ve observed attempts to steal intellectual property belonging to gaming companies such as source code and internal systems design.

Who are the attackers? What countries are they from?

Our research revealed that the attackers’ used Chinese language in the code of the malware; they used Chinese locale in their Windows servers and they have been using a number of IP addresses in China. There are a number of other indicators, such as nicknames, timezones and more showing that the attackers are located in the People’s Republic of China.

For example, multiple virtual personas related to the Winnti malware appeared on specific Chinese forums about hacking/vulnerabilities/network security topics. We have tracked one such persona down to ad tenancy in Luoyang, Central China.

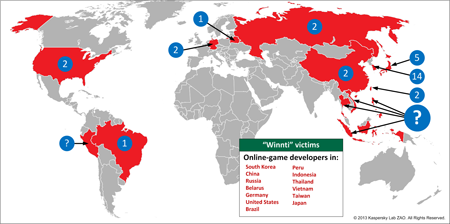

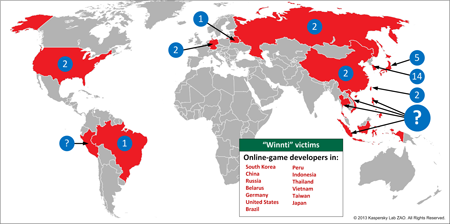

Who are the victims? What is the scale of the attack?

The majority of the victims are software development companies, most of which are producing online video games from South East Asia. We have counted 35 unique compromised businesses over the last year and a half. From the other side we revealed 227 domain names created by the attackers and used as Command & Control servers in different campaigns.

Why are the attackers focused on on SE Asia?

This is most likely related to the geography of the attackers’ home and their interests in local software developers. It seems that the attackers were interested in gaining access to local popular software vendors. The reason behind that is unclear, they probably wanted to get a hold on digital certificates and access to software production processes of local software developers to be able to attack other local organizations or get a potential to infect a large number of local users at any time.

How are users (both home and corporate) protected against those types of attack?

All Kaspersky Lab customers are protected now with regular updates of anti-malware bases. We would like to recommend that all other users to stay cautious when opening attachments that arrive in suspicious e-mails as this was exactly the technique used to spread the malware.

Can you describe the different stages of this attack? For example, did the attackers compromise gaming companies servers first, and then use the compromised servers (and signed certificates) to distribute malware to end-users (gamers)?

In most of cases we have seen targeted attacks which started from a spear phishing email sent to one or a few company mailboxes. The emails had a malicious attachment in self-extracting or regular archive with an executable. We haven’t seen any zero-day vulnerabilities used by this particular group. After the initial penetration of a corporate network, the attackers uploaded a set of tools to the infected machine to scan the network resources, escalate privileges and locate the most valuable information in the attacked organization. Next, the attackers exfiltrated stolen data in compressed form to one of their C&C servers on the internet, normally by using back-connect TCP channel through a chain of simple TCP-proxy applications.

As for the compromised server, yes we have seen incidents when the malware was available for download from public server of gaming companies, but the component we have seen on the server wasn’t enough to successfully infect end-users’ machines and most likely got there by accident.

How are the attackers profiting from this? Is it done by online game manipulations or are they making money by stealing personal user data/files/credentials from infected machines via the backdoor (not related to in-game play)?

We believe that the main objective of the attackers is to collect digital certificates, steal intellectual property of the software developing companies, which normally includes source code of their products, and theft of in-game virtual gold/currency in MMORPGs. While digital certificates could be sold on the underground market to other attackers, the source code brings more opportunities from in-game exploitation of vulnerabilities to create of shadow copies of the online game business in the local region of the attackers.

If it’s done via in-game play, can you explain how this is done? Are they exploiting vulnerabilities in the compromised games to create rogue amounts of in-game currency (gold/runes/coins/etc) and then sell the fake in-game currency to other players for real money?

We currently don’t have full confirmation that the attackers abused games to generate fake currencies as we didn’t have full access to the gaming servers that were compromised by the attackersbut, according to some reports from the gaming companies, some malicious modules were injected into the process of game servers and most likely were used to manipulate the internal state of the process, which most likely leads to production of rogue amounts of in-game currency or any other valuable game objects.

Which gaming companies were targeted? Which games were targeted?

We disclose the list of companies which digital certificates were stolen and abused by the attackers. However, the list doesn’t include all compromised companies we know. Some of the companies we worked with voluntarily assisted our research and investigation but preferred to remain anonymous. Below is the list of companies that had their certificates stolen:

- ESTsoft Corp

- Kog Co., Ltd.

- LivePlex Corp

- MGAME Corp

- Rosso Index KK

- Sesisoft

- Wemade

- YNK Japan

- Guangzhou YuanLuo

- Fantasy Technology Corp

- Neowiz

Also Winnti samples contain tags that could mean companies that were breached or had been compromised and to which the samples are/were destined. Among them we have recognized following companies:

- Cayenne Entertainment Technology Co.,Ltd, Taiwan, tag: Wasabii

- AsiaSoft, Thailand, tag: asiasoft

- GameNet, Russia, tag: GameNet

- NEXON Corporation, Japan, tag: nexon

- VNG Corporation, Viet nam, tag: zing

- Trion Worlds, USA, tag: TRIONWORLD

- EYAsoft, South Korea, tag: eyaap80

- NCsoft, South Korea, tags: aion5000, aion2008

- Zemi Interactive, South Korea, tag: zemi

- NHN Corporation, South Korea, tag: NHN

- Hangame Japan, Japan, tag: hangame.jp

Did you identify any unique characteristics during your analysis that indicated who the attackers might be?

Yes, we were able to collect a few unique characteristics of the attackers:

- The time zone when the attackers were active: most likely between GMT +07 and GMT+09.

- Chinese simplified locale set in the resource section of some malicious modules. Chinese text strings used in the report messages of some modules.

- Chinese hacking team name used as a password for special backdoor.

- Chinese user profiles involved in posting control messages on public Internet resources (blogs and forums).

- Chinese system locale used at C&C servers (via RDP connection).

Have any of these characteristics been identified in other targeted campaigns not related to gaming?

Certificates of gaming companies were used in attacks against Tibetan and Uyghur activists:

- https://securelist.com/new-uyghur-and-tibetan-themed-attacks-using-pdf-exploits-45/35465/

- https://www.f-secure.com/weblog/archives/00002524.html

Some additional industries including the aerospace:

We also observed that SK Communications, the owner of the largest social network CyWorld in South Korea and the popular South Korean web portal Nate, had been hacked back in 2011 and an infection spread there from another company ESTsoft to which the Winnti team had first penetrated:

- https://media.kasperskycontenthub.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/43/2013/04/20082912/C5_APT_SKHack.pdf

Could the Winnti attackers be involved in any additional campaigns that occurred in the past?

Based on the general perception of the Winnti operations, we believe that the attackers that currently form the Winnti group used to be members of Chinese underground hacking teams. It is most likely that they were attacking various entities including businesses and individuals as members of those groups, but united in Winnti group they have started doing that routinely, systematically and under well-organized management. The ex-members of various hacking teams were united and started doing penetrations at a professional level.

What does this campaign mean to someone who isn’t an online gamer or gaming company? Is the Winnti Crew attacking other targets as well?

There have been few incidents when non-gaming companies were compromised, however the main focus of the Winnti group is currently game developers. Nevertheless there is no reason why the Winnti group wouldn’t move to other types of businesses in the future, because their attack tools are universal and may be used against any other target.

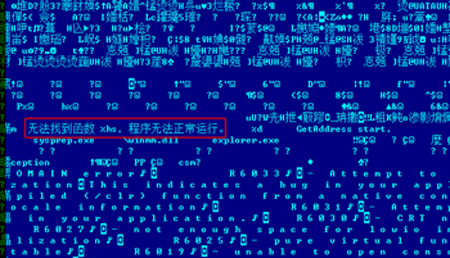

Are there any unique infection symptoms that end-users should be aware of (BSOD, open ports, etc.)?

The malware that we have analyzed uses rootkit approach while running on the system. It starts as a system driver and loads additional components in memory. The end-user will most likely see no changes compared to the uninfected system.

What should companies in the gaming industry do to verify their servers weren’t compromised?

The easiest way for system administrators would be to deploy an anti-malware engine in a product or a standalone tool (such as Kaspersky Security Scan) as all the malicious files are currently detected with our anti-malware databases.

What should end-users do to check if their systems were compromised?

It is possible for a common user to manually check if the system is compromised. Normally it can be recognized by local files on disk with names apphelp.dll and winmm.dll which are located outside %WINDIR%System32 directory. Traditionally, the attackers place these files in %WINDIR%, which is a good indicator of a compromised system.

Winnti FAQ. More Than Just a Game