Recently, in our never-ending quest to protect the world from malware, we found a misbehaving Android trojan. Although malware targeting the Android OS stopped being a novelty quite some time ago, this trojan is quite unique. Instead of attacking a user, it attacks the Wi-Fi network the user is connected to, or, to be precise, the wireless router that serves the network. The trojan, dubbed Trojan.AndroidOS.Switcher, performs a brute-force password guessing attack on the router’s admin web interface. If the attack succeeds, the malware changes the addresses of the DNS servers in the router’s settings, thereby rerouting all DNS queries from devices in the attacked Wi-Fi network to the servers of the cybercriminals (such an attack is also known as DNS-hijacking). So, let us explain in detail how Switcher performs its brute-force attacks, gets into the routers and undertakes its DNS-hijack.

Clever little fakes

To date, we have seen two versions of the trojan:

- acdb7bfebf04affd227c93c97df536cf; package name – com.baidu.com

- 64490fbecefa3fcdacd41995887fe510; package name – com.snda.wifi

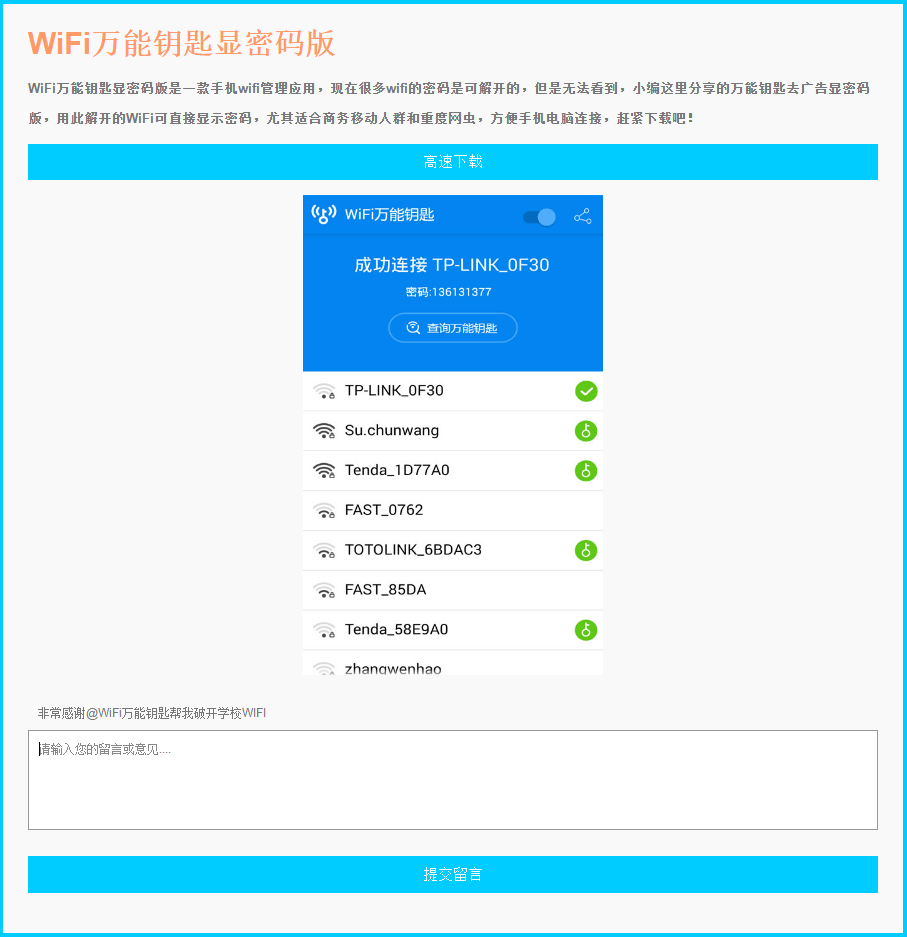

The first version (com.baidu.com), disguises itself as a mobile client for the Chinese search engine Baidu, simply opening a URL http://m.baidu.com inside the application. The second version is a well-made fake version of a popular Chinese app (http://www.coolapk.com/apk/com.snda.wifilocating) for sharing information about Wi-Fi networks (including the security password) between users of the app. Such information is used, for example, by business travelers to connect to a public Wi-Fi network for which they don’t know the password. It is a good place to hide malware targeting routers, because users of such apps usually connect with many Wi-Fi networks, thus spreading the infection.

The cybercriminals even created a website (though badly made) to advertise and distribute the aforementioned fake version of com.snda.wifilocating. The web server that hosts the site is also used by the malware authors as the command-and-control (C&C) server.

The infection process

The trojan performs the following actions:

- Gets the BSSID of the network and informs the C&C that the trojan is being activated in a network with this BSSID

- Tries to get the name of the ISP (Internet Service Provider) and uses that to determine which rogue DNS server will be used for DNS-hijacking. There are three possible DNS servers – 101.200.147.153, 112.33.13.11 and 120.76.249.59; with 101.200.147.153 being the default choice, while the others will be chosen only for specific ISPs

- Launches a brute-force attack with the following predefined dictionary of logins and passwords:

- admin:00000000

- admin:admin

- admin:123456

- admin:12345678

- admin:123456789

- admin:1234567890

- admin:66668888

- admin:1111111

- admin:88888888

- admin:666666

- admin:87654321

- admin:147258369

- admin:987654321

- admin:66666666

- admin:112233

- admin:888888

- admin:000000

- admin:5201314

- admin:789456123

- admin:123123

- admin:789456123

- admin:0123456789

- admin:123456789a

- admin:11223344

- admin:123123123

- If the attempt to get access to the admin interface is successful, the trojan navigates to the WAN settings and exchanges the primary DNS server for a rogue DNS controlled by the cybercriminals, and a secondary DNS with 8.8.8.8 (the Google DNS, to ensure ongoing stability if the rogue DNS goes down). The code that performs these actions is a complete mess, because it was designed to work on a wide range of routers and works in asynchronous mode. Nevertheless, I will show how it works, using a screenshot of the web interface and by placing the right parts of the code successively.

-

If the manipulation with DNS addresses was successful, the trojan report its success to the C&C

The trojan gets the default gateway address and then tries to access it in the embedded browser. With the help of JavaScript it tries to login using different combinations of logins and passwords. Judging by the hardcoded names of input fields and the structures of the HTML documents that the trojan tries to access, the JavaScript code used will work only on web interfaces of TP-LINK Wi-Fi routers

So, why it is bad?

To appreciate the impact of such actions it is crucial to understand the basic principles of how DNS works. The DNS is used for resolving a human-readable name of the network resource (e.g. website) into an IP address that is used for actual communications in the computer network. For example, the name “google.com” will be resolved into IP address 87.245.200.153. In general, a normal DNS query is performed in the following way:

When using DNS-hijacking, the cybercriminals change the victim’s (which in our case is the router) TCP/IP settings to force it to make DNS queries to a DNS server controlled by them – a rogue DNS server. So, the scheme will change into this:

As you can see, instead of communicating with the real google.com, the victim will be fooled into communicating with a completely different network resource. This could be a fake google.com, saving all your search requests and sending them to the cybercriminals, or it could just be a random website with a bunch of pop-up ads or malware. Or anything else. The attackers gain almost full control over the network traffic that uses the name-resolving system (which includes, for example, all web traffic).

You may ask – why does it matter: routers don’t browse websites, so where’s the risk? Unfortunately, the most common configuration for Wi-Fi routers involves making the DNS settings of the devices connected to it the same as its own, thus forcing all devices in the network use the same rogue DNS. So, after gaining access to a router’s DNS settings one can control almost all the traffic in the network served by this router.

The cybercriminals were not cautious enough and left their internal infection statistics in the open part of the C&C website.

According to them, they successfully infiltrated 1,280 Wi-Fi networks. If this is true, traffic of all the users of these networks is susceptible to redirection.

Conclusion

The Trojan.AndroidOS.Switcher does not attack users directly. Instead, it targets the entire network, exposing all its users to a wide range of attacks – from phishing to secondary infection. The main danger of such tampering with routers’ setting is that the new settings will survive even a reboot of the router, and it is very difficult to find out that the DNS has been hijacked. Even if the rogue DNS servers are disabled for some time, the secondary DNS which was set to 8.8.8.8 will be used, so users and/or IT will not be alerted.

We recommend that all users check their DNS settings and search for the following rogue DNS servers:

- 101.200.147.153

- 112.33.13.11

- 120.76.249.59

If you have one of these servers in your DNS settings, contact your ISP support or alert the owner of the Wi-Fi network. Kaspersky Lab also strongly advises users to change the default login and password to the admin web interface of your router to prevent such attacks in the future.

Switcher: Android joins the ‘attack-the-router’ club

Melanie

Is it possible to update the phone’s firmware to patch this security issue? Perhaps a better question is – is there a patch available for this?

Securelist

Switcher do not use any Android vulnerabilities, so there is no need to patch phone’s firmware. Instead, it is better to change router’s default password and install AV product on the phone to prevent an infection.

John

For users who are not technical expert, I’ll recommended to buy newest Netgear routers because it does not use any default password. Instead, it will ask you to setup the password and security questions for the first time and that’s all.

Nigel

great,but how to get the C&C website internal infection statistics ?

and when I try dig google.com @101.200.147.153 it looked like nothing different

marc41

This wouldn’t be a problem if the phone (or other device) allowed DHCP to assign an IP address but not the DNS server(s) to use. The phone could have ‘static’ DNS entries which would then not be affected by changes at the router.

Facebook

The malware as explained above using the Trojan.AndroidOS example shows that the switcher does not attack users directly. Instead, it targets the entire network, exposing all its users to a wide range of attacks. It’s well-read but needs updating on a regular basis.