For almost a year, an ongoing campaign to infiltrate computer systems throughout the Middle East has targeted individuals across Iran, Israel, Afghanistan and others scattered across the globe.

Together with our partner, Seculert, weve thoroughly investigated this operation and named it the Madi, based on certain strings and handles used by the attackers. You can read the Seculert analysis post here: http://blog.seculert.com/2012/07/mahdi-cyberwar-savior.html”.

The campaign relied on a couple of well known, simpler attack techniques to deliver the payloads, which reveals a bit about the victims online awareness. Large amounts of data collection reveal the focus of the campaign on Middle Eastern critical infrastructure engineering firms, government agencies, financial houses, and academia. And individuals within this victim pool and their communications were selected for increased monitoring over extended periods of time.

This post is an examination of the techniques used to spread the Madi malware to victim systems, the spyware tools used, and quirks about both. In some cases, targeted organizations themselves don’t want to provide further breach information about the attack, so some perspective into the parts of the campaign can be limited.

The Arrival

Social engineering schemes to drop and run spyware

The Madi attackers rely mostly on social engineering techniques to distribute their spyware:

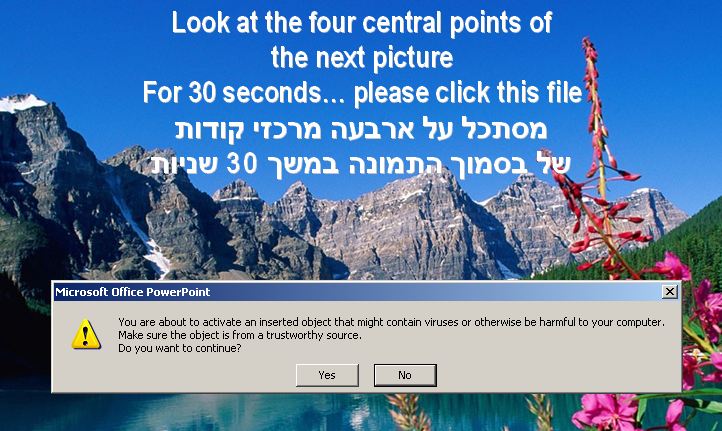

The first of the two social engineering schemes that define spreading activity for this surveillance campaign is the use of attractive images and confusing themes embodied in PowerPoint Slide Shows containing the embedded Madi trojan downloaders. An “Activated Content” PowerPoint effect enables executable content within these spearphish attachments to be run automatically. These embedded trojan downloaders in turn fetch and install the backdoor services and related “housekeeping” data files on the victim system. One example, “Magic_Machine1123.pps”, delivers the embedded executable within a confusing math puzzle PowerPoint Slide Show where the amount of math instructions may overwhelm a viewer. Note that while PowerPoint presents users a dialog that the custom animation and activated content may execute a virus, not everyone pays attention to these warnings or takes them seriously, and just clicks through the dialog, running the malicious dropper.

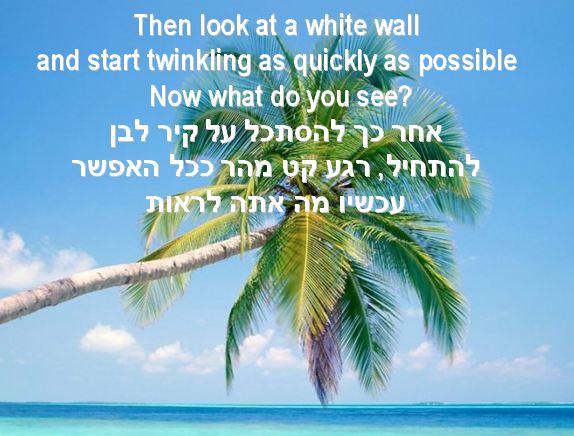

Another PowerPoint Slide Show named Moses_pic1.pps walks the viewer through a series of calm, religious themed, serene wilderness, and tropical images, confusing the user into running the payload on their system as seen below:

And:

And:

Some of the downloaders also drop and open documents with Middle Eastern news content and religious themes as well, as seen here.

Social engineering – Right to left override (RTLO) techniques

Like many pieces of this puzzle, most of the components are simple in concept, but effective in practice. No extended 0-day research efforts, no security researcher commitments or big salaries were required. In other words, attacking this set of victims without 0-day in this region works well enough.

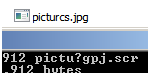

In addition to the attractive PowerPoint Slide Shows frequently delivered within password protected zip archives, the attackers sent out executables maintaining misleading file names using the publicly known “Right to Left Override” technique. These file names appear to the user as image files with harmless .jpg extensions, .pdf extensions, or whatever a determined attacker might craft along with the matching file type icons, leading users to believe they can just click on what is not a data file, but an executable file.

The issue exists with the way Windows handles Unicode character sets. The technique has been written up here and here. Madis related incident files included filenames that appeared on victim systems as “picturcs..jpg”, along with a common .jpg icon. But when that Unicode, or UTF-8 based filename is copied to an ANSI file, the name is displayed as “pictu?gpj..scr”. So some Madi victims were tricked into clicking on what they thought was a harmless .jpg, and instead ran the executable “.scr” file. A screenshot presents an example filename here, with the flawed Widows explorer display above, and the command line display below:

When executed, these PE droppers will attempt to show misleading images or videos, once again, tricking the victim into believing nothing is wrong. Heres a video about a missile test:

And a nuclear explosion photo:

Finding Presence

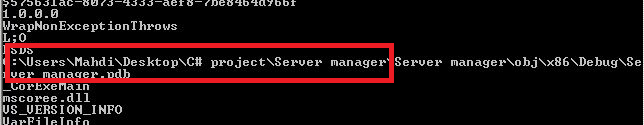

The backdoors that were delivered to approximately 800 victim systems were all coded in Delphi. This would be expected from more amateur programmers, or developers in a rushed project. Here is a screenshot of the interface for the admins:

The executables are packed with a recent version of the legitimate UPX packer such as UPX 3.07. Unfortunately, that technique and quickly shifting code will get the code past some gateway security products.

When run, most versions of the dropper create a large volume of files in c:documents and settingsPrinthood. Along with UpdateOffice.exe or OfficeDesktop.exe (and other variations on the Office name), hundreds of mostly empty, housekeeping files are created. Heres a short list of files keeping configuration data:

| FIE.dll | Filename extension | |

| xdat.dll | Last check-in date | |

| BIE.dll | Distraction filename extension | |

| SHK.dll, nam.dll | Victim directory path prefix (i.e. abamo9 <- this is the operator/handler name for this victim) | |

| SIK.dll | Domain check-in (i.e. www.maja.in) |

Also dropped and opened are any one of several distraction images and documents. One of the documents is the Jesus image posted above (dropped as encoded content within Motahare.txt), and one of the documents is a copy and paste job of an article at The Daily Beast on electronic warfare in the region, which was dropped as encoded content within Mahdi.txt.

Infostealers are downloaded and run as iexplore.exe from within the templates directory mentioned above.

Functionality list:

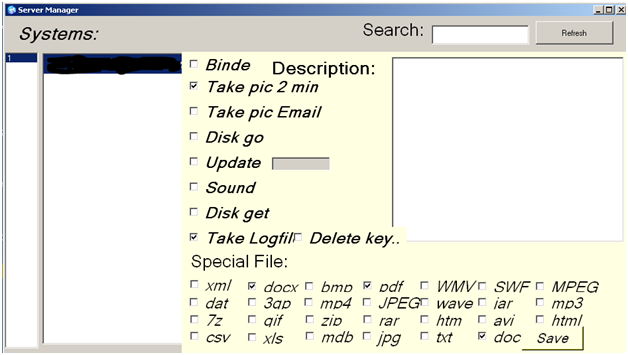

The functionality in the backdoor software mirrors the options present in the configuration tool. Notice the nine different options:

- Keylogging

- Screenshot capture at specified intervals. (see timers below)

- Screenshot capture at specified intervals, initiated exclusively by a communications-related event. The event may be that the victim is interacting with webmail, an IM client or social networking site. These triggering sites include Gmail, Hotmail, Yahoo! Mail, ICQ, Skype, google+, Facebook and more.

- Update this backdoor

- Record audio as .WAV file and save for upload

- Retrieve any combination of 27 different types of data files

- Retrieve disk structures

- Delete and bind these are not fully implemented yet

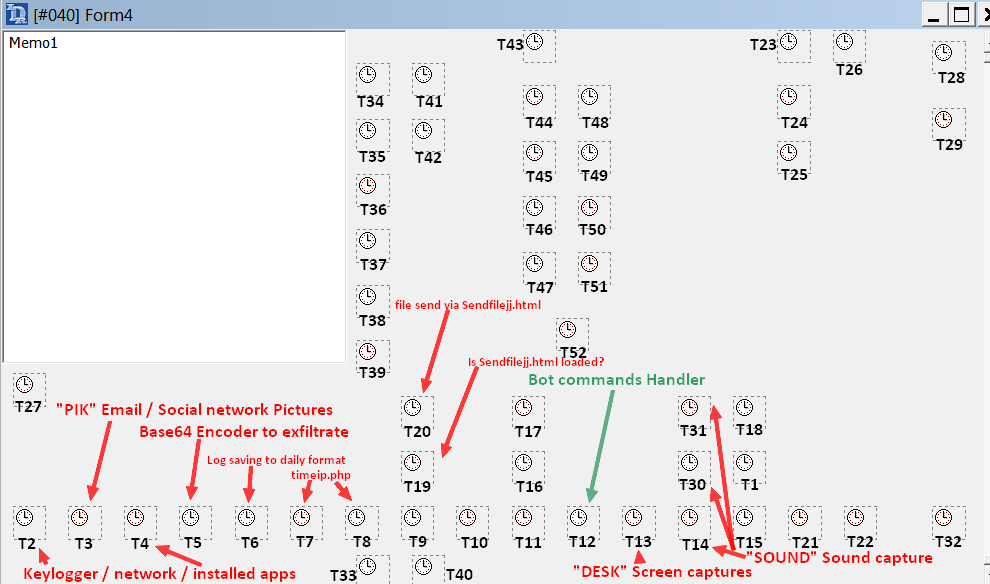

The various operations of the backdoor are controlled by Delphi Timers, as seen below:

Using a disinfected version of Resource Hacker

It’s common behavior for malware to maintain malicious code in their resource section, decompress it on the fly and drop it to disk. Or, for attackers to modify the icons of their RTLO spearphish.

The Madi attackers maintain two copies of ResHacker (see http://www.angusj.com/resourcehacker/ ) for distribution on their websites, embedded within files “SSSS.htm” and “RRRR.htm”. They not only created more noise on the wire by instructing their malware to download ResHacker, a well known resource section editor, but it looks like they have had problems with virus infections on their own networks. These copies differed by one byte. That difference is the value in the SizeofImage section, 0xdc800 in one file, and 0xde000 in the other. The difference presents itself because both were infected with Virus.Win32.Parite.b (https://threats.kaspersky.com/en/threat/Virus.Win32.Parite.b) at some point, and then cleaned by Anti-Virus scanners. So it’s possible and likely that the attackers are bumbling through infections of their own.

Indicators of compromise

All known compromised systems are known to communicate over HTTP with one of several web servers, such as: 174.142.57.* (3 servers) and 67.205.106.* (one server).

In addition, ICMP PING packets are sent to these servers to check their status.

The infostealers are downloaded and executed from the c:Documents and Settings%USER%Templates folder. The downloader itself runs from c:documents and settings%USER%Printhood, which may contain over 300 files with .PRI, .dll, and .TMP extensions. The infostealers are named “iexplore.exe”, while the downloaders maintained names like UpdateOffice.exe or OfficeDesktop.exe.

At the time of writing, the campaign continues to be in operation and we are working with various organizations to clean up and prevent further infections. Kaspersky products detect the malware as Trojan.Win32.Madi.*; some of the older variants are detected as “Trojan.Win32.Upof.*”.

Related MD5s, not a complete list:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 |

7b7abab9bc4c49743d001cf99737e383 a9774d6496e1b09ccb1aeaba3353db7b 885fcebf0549bf0c59a697a7cfff39ad 4be969b977f9793b040c57276a618322 ea90ed663c402d34962e7e455b57443d aa6f0456a4c2303f15484bff1f1109a0 caf851d9f56e5ee7105350c96fcc04b5 1fe27986d9d06c10e96cee1effc54c68 07740e170fc9cac3dcd692cc9f713dc2 755f19aa99a0ccba7d210e7f79182b09 35b2dfd71f565cfc1b67983439c09f72 d9a425eac54d6ca4a46b6a34650d3bf1 67c6fabbb0534090a079ddd487d2ab4b e4eca131cde3fc18ee05c64bcdd90299 c71121c007a65fac1c8157e5930d656c a86ce04694a53a30544ca7bb7c3b86cd 7b22fa2f81e9cd14f1912589e0a8d309 061c8eeb7d0d6c3ee751b05484f830b1 3ab9c5962ab673f62823d8b5670f0c07 1c968a80fa2616a4a2822d7589d9a5b4 1593fbb5e69bb516ae32bec6994f1e5d 133f2735e5123d848830423bf77e8c20 01dc62abf112f53a97234f6a1d54bc6f 18002ca6b19c3c841597e611cc9c02d9 046bcf4ea8297cdf8007824a6e061b63 89057fc8fedc7da1f300dd7b2cf53583 461ba43daa62b96b313ff897aa983454 d0dd88d60329c1b2d88555113e1ed66d 9c072edfb9afa88aa7a379d73b65f82d b86409e2933cade5bb1d21e4e784a633 3fc8788fd0652e4f930d530262c3d3f3 15416f0033042c7e349246c01d6a43a3 f782d10eab3a7ca3c4a73a2f86128aad cfd85a908554e0921b670ac9e3088631 abb49a9d81ec2cf8a1fb4d82fb7f1915 b2b4d7b5ce7c134df5cb40f4c4d5aa6a 8b01fc1e64316717a6ac94b272a798d4 81b2889bab87ab25a1e1663f10cf7e9e 3702360d1192736020b2a38c5e69263a 8139be1a7c6c643ae64dfe08fa8769ee 331f75a64b80173dc1d4abf0d15458cc 398168f0381ab36791f41fa1444633cc d6f343e2bd295b69c2ce31f6fe369af9 f45963376918ed7dc2b96b16af976966 |

Part II of this blogpost will examine the broader picture infrastructure, communications, data collection, and victims.

The Madi Campaign – Part I