Pandora’s Box

It was the Stuxnet worm that became the first cyber-weapon whose deployment became well known to the general public. Intentional or not, the people behind Stuxnet opened a Pandora’s box – showing the world how effective an attack on an industrial facility can be. It’s easy for just about anyone to comprehend the potentially devastating effects of a possible future attack on installations in the energy, industrial, financial or other spheres.

After the discovery of Stuxnet, several other close “relatives” were detected: Duqu, Flame and Gauss. These programs have several traits in common, but their targets, functionality and creation timestamps all differ. Unfortunately, this is not the full list of known malware capable of spying and/or carrying out acts of sabotage – the grim reality is that the war arsenals of several countries now include cyber-weapons. In the past, states resorted to diplomatic, economic and military means to uphold their geo-political interests; now, instead of warplanes, rockets, tanks and battleships they can deploy specialized malware to achieve their ends. If successfully deployed, cyber-weapons not only produce the desired effect but do so at a fraction of the cost and with a minimum of noise – ideally anonymously. One example of this was found in the recent incident involving Wiper malware, which demonstrated once again just how effective this approach can be.

The leading world powers are already openly discussing the need to defend against enemy activity in cyberspace as well as their plans to build up their own cyber-warfare capabilities. This in turn forces other states to follow suit and have their own highly qualified teams of programmers and hackers to develop specialized cyber-resources – both for defensive and offensive purposes. A cyber-arms race is now well underway.

Today, in order to defend its sovereignty a state not only has to defend its socio-economic and political interests but also effectively protect its cyberspace. And protecting specifically the key information infrastructure of critical, life-supporting facilities is what states understandably usually consider to be top priority.

The Anatomy of an Attack

Cyber-attacks pose the greatest danger to countries and their populations should they target the key information infrastructure that controls and manages critically important installations, like power stations, reservoirs, electricity grids, pipelines, transportation and telecommunications networks, etc. If these facilities are put out of action, it is clear that chaos and catastrophe could well follow. And in one way or another our daily lives depend on these systems. They heat our homes, supply them with water and electricity, support broadcasting, and control the extraction of natural resources and production processes in factories.

But it’s not just industrial and infrastructural facilities that are potential targets for cyber-attacks. Any unauthorized access to data can cause serious problems for numerous types of organizations, including banks, medical and military facilities, research institutes and most businesses. However, in this article we will restrict our discussion to the protection of industrial/infrastructural facilities.

The software used to manage key information infrastructure is unfortunately not without its bugs and vulnerabilities. According to research conducted by Carnegie Mellon University, military and industrial software contains between five and 10 defects for every thousand lines of code. And that’s software shipped to end-users that has passed testing. So when considering that the kernel of a Windows operating system has over five million lines of code, and Linux – 3.5 million, it’s not difficult to calculate the number of theoretically possible vulnerabilities that could be exploited for carrying out a cyber-attack.

Nevertheless, for a cyber-attack to fulfill its mission, the attackers still must have excellent knowledge of the internal workings of the targeted facility. Thus, attacks usually consist of several stages.

The first stage is essentially reconnaissance to gather information about the schematics of the network of the target, and the specific features and characteristics of hardware and software used. At this stage, rather than the target itself being studied, often its contractors are – for example systems integrators. This is because they are generally less attentive when it comes to security, but at the same time they possess valuable data on the target. Moreover, these contractors have authorized access to the targeted network, something that the attackers can exploit at the next stage of the attack. This first reconnaissance stage can also involve service companies, partners and hardware suppliers being snooped on.

At the second stage the collected data is carefully analyzed and then the most effective attack vector is selected. This dictates which vulnerability in the program code is to be used to penetrate the system, and what sort of functionality the malware needs to achieve its objectives. A malicious program is then crafted with the required “warhead”.

After that, if possible, the malware is tested on the same software/hardware setup used by the target.

Lastly, there’s the question of the method to be used to deliver the malicious program to the target. The possibilities here range from relatively straightforward social engineering techniques to hi-tech penetration methods via secure communication channels. And as the Flame malware’s MD5 crypto-attack has shown, where there’s a will, persistence and sufficient computing power, an awful lot can be achieved by such hi-tech methods.

Industrial Control Systems

When it comes to key information infrastructure protection there are two especially serious problems: deficiencies in the security models devised for industrial/critical systems, and shortcomings in the environments where those models are implemented.

Until recently the prevailing view was that, when creating information security models for critically important industrial/infrastructural installations, physically isolating the installation was sufficient to protect it – based on the principles of “security by obscurity” and “air gap”. However, Stuxnet demonstrated that those principles no longer work (its target was physically isolated) and that this approach to security is outdated.

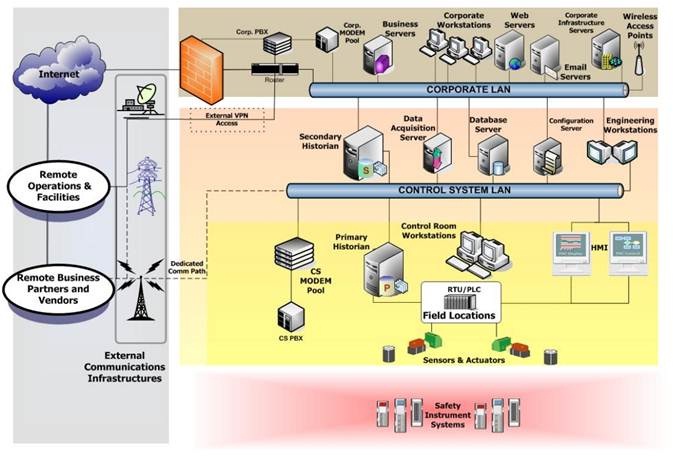

The key information infrastructure at industrial/critical facilities is made up of industrial (automation/process) control systems (ICS) and industrial safety systems. The security of the entire facility depends on these systems’ monitoring functioning smoothly and correctly.

When it comes to software and hardware, ICS is inherently heterogeneous. A typical operations/processes network at an enterprise includes SCADA servers managed by Windows or Linux, database servers (SQL Server or Oracle), programmable logic controllers (PLC) of various manufacturers, human machine interfaces (HMI), intelligent sensors, and corporate ERP systems. And the latest research by the US Department of Homeland Security suggests there are an average of 11 direct connections between the operations/processes network and the corporate network.

The particular features to be found in ICS depend on a number of factors, such as how experienced the systems integrators are, their notions of how economically viable a protection method is, current trends in automation, and many more.

In the vast majority of cases protecting ICS is not very high on the list of priorities for systems integrators. Of course, these software-hardware systems are subject to certification, but this usually boils down to nothing more than a bureaucratic procedure.

The Problem of Vulnerability

To get an understanding of just how vulnerable ICS can be, one only has to look at how long its service life normally lasts: decades. Besides, up until the mid-2000s the term “software vulnerability” didn’t even exist, and if in the development of systems any security issues arose from such vulnerabilities, they were simply not taken any notice of. Thus, the majority of automated control systems used in industrial/infrastructural operations/processes networks today were created with no notion whatsoever of any possibility of cyber-attacks. For example, most protocols used for the exchange of information used in SCADA and PLC don’t require any user identification or authorization. This means that any device that gets connected to an industrial/infrastructural operations/processes network is able to receive and emit control commands to any other device in that network.

There’s another serious problem with the ICS status quo: with such a long life cycle, updating or installing new software onto the system is normally either forbidden by the given organization’s regulations, or involves significant bureaucratic and technical difficulties. For many years ICS was generally not updated at all. And all the while openly on the Internet there was and still is published detailed information on vulnerabilities of controllers and SCADA systems, operating systems, database management systems (DBMS), and even smart sensors.

Then there are the companies that manufacture SCADA and PLC – they too have hardly helped the cyber-security situation with regard to their products. The ICS-CERT news archive has demonstrated in detail how vendors pay scant attention to the security of their equipment – be it software or hardware. Hardwired PLC logins, passwords, SSH and SSL-keys, the possibility of attacks on systems due to an overflowing buffer, and also the possibility of substituting system components with malicious ones and carrying out DoS and XSS attacks. And these are just the most common vulnerabilities.

Further, the majority of vendors install on their hardware-software suites remote admin programs, while leaving the configuration thereof to systems integrators. But integrators often pay little attention to their settings, resulting ICS not infrequently being accessible via the Internet with the default login and password. And on the Internet there are customized search engines able to locate devices to which access is possible with the use of a default login and password, or without them at all. Thus, anyone who might want to can easily perform remote control of a critical system – from the other side of the planet.

The above-described vulnerability issues all translate into a situation where ICS components can be broken into, infected, made to work incorrectly or completely malfunction, and where those same ICS components can issue engineers false reports and encourage them to take inappropriate actions, which, in turn, could cause serious emergency situations.

Of course, at every industrial/infrastructural facility there exist industrial safety systems. But these are only intended for shutting down equipment when things go very wrong. They are completely unsuited to, and so not much use for, protecting against carefully prepared targeted cyber-attacks.

Besides, industrial safety systems are manufactured by many different companies. Each of which – should they decide to go rogue – has the possibility to build hidden functionality into those systems at various levels – from the process management software to the microchip of the processor.

Historically, companies manufacturing industrial equipment and software concentrated on stability and fault tolerance in their products. And until recent times such an approach was, without question, justified; however, the time has come for them to start paying serious attention to providing security too – by cooperating with specialized companies to get their expert input on security.

The world is lately finding itself in a situation where, on the one hand, several countries already possess cyber-weapons, while on the other – countries’ key information systems are vulnerable to attack. The overall level of development of IT in a country, plus the degree of automation at a specific industrial facility, of course will affect just how attackable a facility is, but nevertheless a cyber-attack is normally always possible.

Trustworthy Information

Solutions are needed right now to provide effective protection to critically important industrial/infrastructural facilities and also organizations likely to suffer from intrusions and data leakage. But no matter how well such solutions are developed, the application in ICS of vulnerable operating systems and software prevents manufacturers of security solutions from guaranteeing the integrity of the systems they are to protect. But for critical installations/ organizations such guarantees are essential.

To expect that all ICS developers will all of a sudden undertake a total check and update of all the software they use, and engineers/managers will promptly update already installed applications, is hardly realistic. And the decades-long life cycles of such systems would suggest that the introduction of new, secure ICS will require probably decades too – until when life cycles start ending and the ICS is replaced.

However, a global solution to the vulnerability issue is not the only possible solution for ensuring the security of the operation of industrial/infrastructural facilities, as shown further below.

But what exactly are vulnerabilities and what’s so dangerous about vulnerable software? Vulnerabilities are mistakes in computer code that can be exploited by a malicious program for getting into a system. Any component of ICS can be infected, and an infected component can execute a malicious action on an industrial operations/processes network that could lead to a serious malfunction, while at the same time misinforming the supervising engineers. In such a situation the engineers have no guarantee that the data reports they get from the systems are accurate, and this is one of the main problems of system security – especially with the cost of a mistake on such kind of facility being extremely high.

For the secure operation of industrial/infrastructural installations it is vitally important for an engineer to be able to obtain reliable information from the operation/process management system – so as to be able to control the operational processes based on that information. This permits avoiding mistakes in controlling the processes, and helps – where necessary – to shut them down in time and avert disaster.

Today there exists neither operating systems nor software that could be applied in industrial/infrastructural environments whose produced data on processes could be fully trusted. And this left us with no other option than to begin developing something new ourselves.

The fundamental means for providing security is the operating system. And for controlling information that circulates on industrial/infrastructural process networks, it is specifically this operating system that needs to be applied. It gives a guarantee that information is accurate and reliable and doesn’t contain malicious elements.

Secure Operating Systems

So what are the requirements for a maximally secure environment for controlling of information infrastructure?

- The operating system can’t be based on existing computer code; therefore, it must be written from scratch.

- To achieve a guarantee of security it must contain no mistakes or vulnerabilities whatsoever in the kernel, which controls the rest of the modules of the system. As a result, the core must be 100% verified as not permitting vulnerabilities or dual-purpose code.

- For the same reason, the kernel needs to contain a very bare minimum of code, and that means that the maximum possible quantity of code, including drivers, needs to be controlled by the core and be executed with low-level access rights.

- In such an environment there needs to be a powerful and reliable system of protection that supports different models of security.

Based on the above key requirements we are creating our own operating system, the main feature of which is the categorical impossibility of running on it undeclared functionality.

Only on the basis of such an operating system is it possible to build a solution allowing an engineer not only to see what’s really going on in an operations/processes system, but also to control and manage it. And this is regardless of which manufacturers produced other operating systems used elsewhere in the processes system or which produced ICS, DBMS, or PLC, and irrespective of their security level or the number of vulnerabilities they might have; what’s more, regardless of their levels of possible contamination.

In essence this is a new generation, intellectual, industrial safety system. It’s a security system that takes into account the whole complex of performance indicators of industrial operations/ processes, or of an overall industrial system, and prevents major malfunctions resulting from incorrect actions of an engineer, from mistakes in ICS software, or from cyber-attacks. Besides, such a system can complement traditional industrial safety systems, adding the ability to monitor more complex incidents.

Such a solution needs to be built into existing ICS to both protect it and provide reliable monitoring, or it needs to be taken into full consideration when designing new ICS. In either case, the solution is to provide the full range of the very latest principles of security.

Conclusion

The world has changed. Governments are actively acquiring cyber-weapons, and this means that adequate means of protection are needed in response. Still, despite the fact that key information infrastructure is extremely important, there exists today no means to properly safeguard it.

Based on existing operating systems, new, fully effective means of protection of key information infrastructure is impossible. At the same time, creating a new secure operating system for all ICS components is a task that’s very difficult and will take a lot of time. But the problem of security of industrial and infrastructural facilities needs to be solved now.

Therefore, what needs to be done in the meantime is first of all to identify the key problems of information security and deal with them. One such key problem lies in the fact that information security systems for industrial/infrastructural facilities rely on unreliable sources of data. Until the day when a totally trustworthy, 100% reliable component gets plugged into an industrial operations/processes network – which component could be trusted completely by the engineer or controlling program complex – the possibility of building effective security systems is just a pipe dream. What’s needed is a trusted computing base on the basis of which it’s possible to build a security system of the required highest standards. And such a trusted base requires at a minimum the presence of a fully secure, trustworthy operating system.

And such a fully secure, trustworthy operating system is what we’re creating. A basis from which security system components will be able to provide accurate information from all ICS. The operating system incorporates a whole range of fundamental security principles, the observation of which will guarantee that at all times it will function the way it was designed to by its developer, and never in a different way. Architecturally, the operating system is constructed in such a way that even a break-in into any of the components or applications loaded onto it won’t allow an intruder to gain control over it or to run malicious code. In taking this approach we are sure that our operating system will be completely reliable and that it could be used as a fully trustworthy source of information, which in turn is the only solid basis for building a security system of a vastly superior degree of effectiveness.

Securing Critical Information Infrastructure: Trusted Computing Base