Cybercriminals use a variety of bots to conduct DDoS attacks on Internet servers. One of the most popular tools is called Black Energy. To date, Kaspersky Lab has identified and implemented detection for over 4,000 modifications of this malicious program. In mid-2008 malware writers made significant modifications to the original version, creating Black Energy 2 (which Kaspersky Lab detects as Backdoor.Win32.Blakken). This malicious program is the subject of this article.

Step-by-step: the bot components

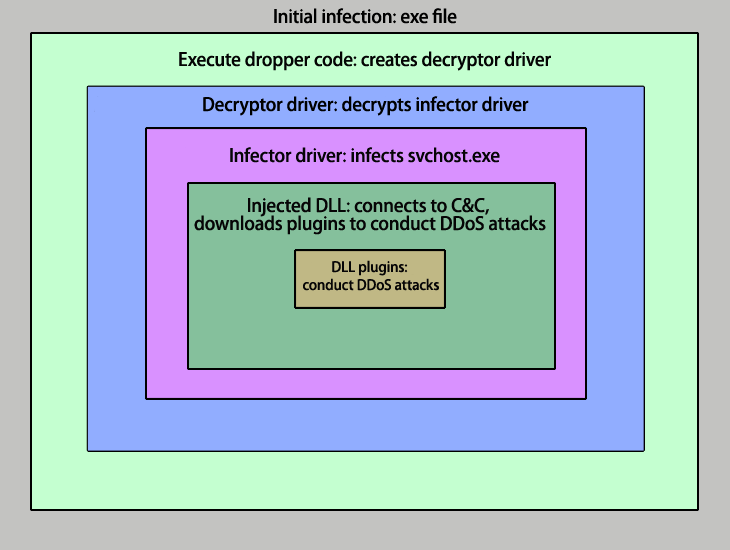

The bot has several main functions: it hides the malware code from antivirus products, infects system processes and, finally, offers flexible options for conducting a range of malicious activities on an infected computer when commands are received from the botnet command-and-control (C&C) center. Each task is performed by a different component of the malicious program.

Figure 1. A step-by-step guide to how Black Energy 2 works

The protective layer

Like most other malicious programs, Black Energy 2 has a protective layer that hides the malicious payload from antivirus products. This includes encryption and code compression; anti-emulation techniques can also be used.

Once the Black Energy 2 executable is launched on a computer, the malicious application allocates virtual memory, copies its decryptor code to the memory allocated and then passes control to the decryptor.

Execution of the decryptor code results in code with dropper functionality being placed in memory. Once the dropper code is executed, a decryptor driver with a random name, e.g. “EIBCRDZB.SYS”, is created in system32drivers. A service (which also has a random name) associated with the driver is then created and started:

Figure 2. The launch of the malicious decryptor driver

Like the original executable, this driver is, in effect, a ‘wrapper’ that hides the most interesting part of the malware.

The infector

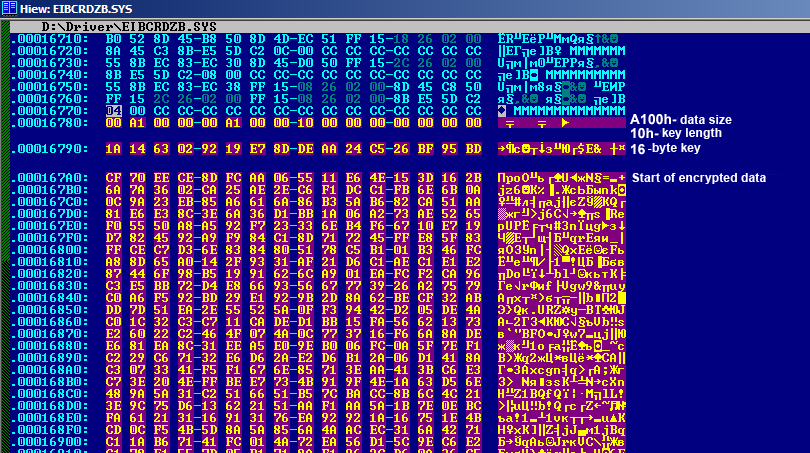

The code of the decryptor driver contains a block of encrypted and packed data:

Figure 3. Encrypted data within the decryptor driver

The data block has the following structure:

Figure 4. Encrypted data structure

The key from this block is used to create another key, 100h bytes in size, which is used to decrypt the archive. The encryption is based on the well-known RC4 algorithm. If the archive size is equal to the data size, it means that the data is not packed. However, if the two do not coincide, the encrypted archive has to be unpacked.

The decrypted data is an infector driver which will inject a DLL into the svchost.exe user-mode process. In order to launch the infector driver, the decryptor driver allocates memory, copies the decrypted code to that memory area, remaps address offset fixups and passes control to it. The malicious DLL is stored in the .bdata section of the infector driver. This data block has the same structure as that described above. The infector driver locates the svchost.exe process and allocates memory in its address space. The malicious DLL is then copied to this memory area and address offsets are remapped according to the relocation table. The injected library’s code is then launched from kernel mode as shown below:

Figure 5. Launching the DLL injected into svchost.exe

This method uses APC queue processing. First, an APC with the address of the DllEntry function for the library injected is initialized, then the APC is queued using KeInsertQueueApc APC. As soon as svchost.exe is ready to process the APC queue (which is almost immediately), a thread from the DllEntry address is launched in its context.

The injected DLL

The DLL which is injected into svchost.exe is the main controlling factor in launching a DDoS attack from an infected computer. Like the infector driver, the DLL has a .bdata section; this includes a block of encrypted data, which has the same structure as that shown above. The data makes up an xml document that defines the bot’s initial configuration. This screenshot gives an example:

Figure 6. The bot’s initial settings

The address of the botnet’s C&C is of course the most important information. In this case, two addresses are given for the sake of reliability: if one server is down and the bot is unable to contact it, the bot can attempt to connect to its owner using the backup address.

The bot sends a preformed http request to the C&C address; this is a string containing data which identifies the infected machine. A sample string is shown below:

The id parameter, which is the infected machine’s identifier, includes the computer name and the serial number of the hard disk on which the C: drive is located. This is followed by operating system data: system language, OS installation country and system build number. The build identifier for the bot ( ‘build_id’ in the initial configuration options xml document) completes the string.

The format of the request string is used as confirmation that the request actually comes from the bot. In addition, the C&C center also uses the user-agent header of the http request as a password of sorts.

If the C&C accepts the request, it responds with a bot configuration file which is also an encrypted xml document. RC4 is also used to encrypt this file, with the infected machine’s identifier (the id parameter of the request string, in the example above – xCOMPUTERNAME_62CF4DEF) serving as a key.

Here is an example of such instructions:

Figure 7. Configuration file – instructions from the C&C

The section tells the bot which modules are available on the owner’s server to set up a DDoS attack. If the bot does not have a particular module or if a newer version is available on the server, the bot will send a plug-in download request to the server, e.g.:

A plug-in is a DLL library, which is sent to the bot in an encrypted form. If the key used to encrypt a plugin differs from the value of the id parameter, it will be specified in the field of the configuration file. Once the plug-in DLL has been received and decrypted, it will be placed in the memory area allocated. It is then ready to begin a DDoS attack as soon as the appropriate command is received.

Plug-ins will be regularly downloaded to infected machines: as soon as the malware writer updates their attack methods, the Black Energy 2 bot will download the latest version of the relevant plugin.

The downloaded plug-ins are saved to the infected computer’s hard drive as str.sys in system32drivers. Str.sys is encrypted, with the id parameter being used as the key. Prior to encryption, the str.sys data looks like this:

Figure 8. Unencrypted contents of str.sys: plug-in storage

Each plug-in has an exported function, DispatchCommand, which is called by the main module – the DLL injected into the svchost.exe process. A parameter (one of the commands from the section in the bot configuration file) is passed to the DispatchCommand function. The plug-in then executes the command.

The main plug-ins

The main plug-ins for Black Energy 2 are ddos, syn and http. A brief description of each is given below.

The ddos plug-in

The server address, protocol and port to be used in an attack are the input for the ddos plug-in. The plug-in initiates mass connections to the server, using the port and protocol specified. Once a connection is established, a random data packet is sent to the server. The following protocols are supported: tcp, udp, icmp and http.

Below is an example of a “ddos_start udp 80” command being carried out:

Figure 9. Creating a socket, UDP protocol

Figure 10-1. Sending data: sendto and the stack

Figure 10-2. Sending data: sendto and the stack

Figure 10-3. What data is sent: a random set of bytes

When the http protocol is specified in the command, the ddos plugin uses the socket, connect and send functions to send a GET request to the server.

The syn plug-in

Unlike the other plug-ins described in this article, the syn plugin includes a network driver. When the plugin’s DllEntry function is called, the driver is installed to system32drivers folder as synsenddrv.sys. The driver sends all the network packets. As can be easily guessed, the DispatchCommand function waits for the main DLL to send it the following parameter: “syn_start ” or “syn_stop “. If the former parameter is received, the plugin begins an attack, if the latter is received, the attack is stopped. An attack in this case consists of numerous connection requests being made to the server, followed by so-called ‘handshakes’, i.e. the opening of network sessions.

Figure 11. SYN attack: SYN->ACK->RST

Naturally, if numerous requests are made from a large number of infected computers, this creates a noticeable load on the server.

The http plug-in

The DDoS attack methods described above are often combated by using redirects: a server with online resources is hidden behind a gateway that is visible to the outside world, with the gateway redirecting requests to the server hosting the resources. The gateway can use a variety of techniques to fend off DDoS attacks and taking it down is not easy. Since the ddos and syn plugins target IP addresses and have no features which allow them to recognize traffic redirects, they can only attack the gateway. Hence, the network flooding that they generate simply does not reach the server hosting Internet resources. This is where the http plugin comes in.

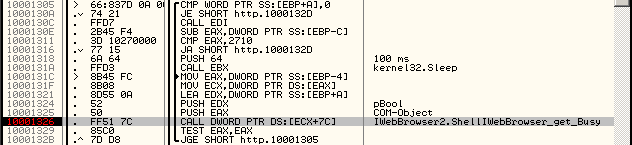

Having received the http_start command, the http plugin creates a COM object named “Internet Explorer(Ver 1.0)” with an IWebBrowser2 interface. The Navigate method is called by the http_start command with the parameter, resulting in the Internet Explorer(Ver 1.0) object navigating to the URL specified. The Busy method is then used by the malicious program which waits until the request is completed.

Figure 12-1. Creating a COM object

Figure 12-2. Pointer to CLSID

Figure 12-3. Pointer to the interface ID

Figure 13. Calling the Navigate method

Figure 14. Calling the Busy method

Using these steps, the malicious program imitates an ordinary user visiting a particular page. The only difference is that, unlike a user, the malicious program makes many ‘visits’ to the same address within a short period of time. Even if a redirecting gateway is used, the http request is redirected to the protected server hosting web resources, thus creating a significant load on the server.

General commands

In addition to downloading plug-ins and executing plug-in commands, Black Energy 2 ‘understands’ a number of general commands that can be sent by the C&C server:

rexec – download and execute a remote file;

lexec – execute a local file on the infected computer;

die – terminate bot execution;

upd – update the bot;

setfreq – set the frequency with which the bot will contact the C&C server;

http – send http request to the specified web page.

Conclusion

Initially, the Black Energy bot was created with the aim of conducting DDoS attacks, but with the implementation of plugins in the bot’s second version, the potential of this malware family has become virtually unlimited. (However, so far cybercriminals have mostly used it as a DDoS tool). Plugins can be installed, e.g. to send spam, grab user credentials, set up a proxy server etc. The upd command can be used to update the bot, e.g. with a version that has been encrypted using a different encryption method. Regular updates make it possible for the bot to evade a number of antivirus products, any of which might be installed on the infected computer, for a long time.

This malicious tool has high potential, which naturally makes it quite a threat. Luckily, since there are no publicly available constructors online which can be used online to build Black Energy 2 bots, there are fewer variants of this malware than say, ZeuS or the first version of Black Energy. However, the data we have shows that cybercriminals have already used Black Energy 2 to construct large botnets, and these have already been involved in successful DDoS attacks.

It is difficult to predict how botnet masters will use their botnets in the future. It’s not hard for malware writers to create a plug-in and get it downloaded to infected user machines. Furthermore, any plug-in code is only present in an infected computer’s memory; in all other instances the malicious modules are encrypted, whether this is during transmission or when stored on a hard drive.

In addition, Black Energy 2 plugins are not executable (.exe) files. Plugins are loaded directly onto an infected machine, which means that they will not be distributed using mass propagation techniques and antivirus vendors may not come across new plugins for extended periods of time. However, it is the plug-ins that ultimately meet the cybercriminals’ goal, i.e. delivering the malicious payload which is the ultimate aim of infecting victim machines with the Black Energy 2 bot.

Consequently, it’s essential to track the plug-ins. Kaspersky Lab monitors which Black Energy 2 plugins are available for download to track the evolution of this malicious program. We’ll keep you posted.

Black DDoS