“Nigerian” spam is a collective term for messages designed to entice victims with alluring offers and draw them into an email exchange with scammers, who will try to defraud them of their money. The original “Nigerian” spam emails were sent in the name of influential and wealthy individuals from Nigeria, hence the name of the scam.

The themes of these phishing emails evolved over time, with cybercriminals leveraging contemporary events and popular trends to pique the interest of their targets. However, the distinctive characteristics of the messages that placed them in the “Nigerian” scam category remained unchanged:

- The user is encouraged to reply to an email. It is usually enough for the attackers to receive a reply in any format, but sometimes they ask the victim to provide additional information, such as contact details or an address.

- Typically, scammers mention a large amount of money that they claim the recipient is entitled to, either due to sheer luck or because of their special status. However, some emails use other types of bait: investment opportunities, generous gifts, invitations to an exclusive community, and so on.

- The body of most “Nigerian” scam emails includes the email address – often registered with a free email service – of the alleged benefactor or an agent, which may be different from the sender’s address. Sometimes the return address is given in the Reply-To field rather than the message itself, and the address also differs from the one in the From field. Alternatively, the message body might contain a phone number in place of an email address.

- The messages are often poorly written, with a large number of mistakes and typos. The text may well be the product of low-quality machine translation or generated by a large language model poorly trained on that language.

Types of “Nigerian” email messages

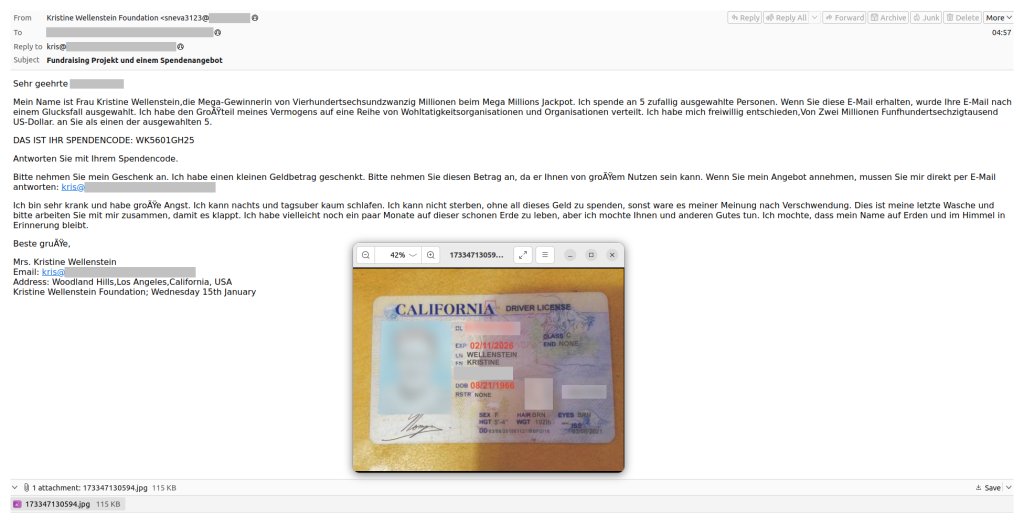

Email from wealthy benefactors

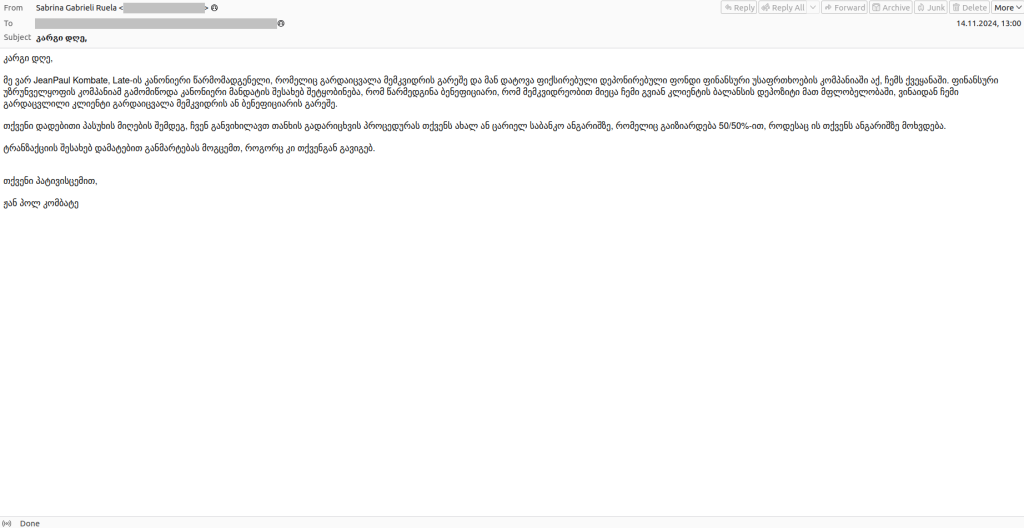

A fairly common tactic that has superseded the original “Nigerian” scam involves messages purportedly from wealthy individuals suffering from a terminal illness and facing imminent death. They claim to have no heirs, and therefore wish to bequeath their vast fortune to the recipient, whom they deem worthy.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 |

Subject: PLEASE READ CAREFULLY From: "Judith Peters"<<>> Reply-To: <attorneycchplain@...> Dearest One I'm Mrs Judith Peters a Successful business Woman dealing with Exportation, I got your mail contact through search in order to let you know my Ugly Situation. Am a dying Woman here in Los Angeles California Hospital Bed in (USA),I Lost my Husband and my only Daughter for Covid-19 in March 2020 I'm dying with a cancer disease at the moment. My Doctor open-up to me that he is Afraid to tell me my Condition and inside me, I already know that I'm not going to survive and I can't live alone without my Family on Earth. I have a project that I am about to hand over to you. and I already instructed the Heritage Bank to transfer my fund sum of $50,000.000.00usd to you, so as to enable you to give 50% to Charitable Home and take 50% for yourself. Don't think otherwise and why would anybody send someone you barely know to help you deliver a message, help me do this for the happiness of my soul. Please, do as I said there was someone from your State that I deeply love so very very much and I miss her so badly I have no means to reach any Charitable Home there,that is why I go for a personal search of the Country and State and I got your mail contact through search to let you know my Bitterness and the situation that i am passing through. Please help me accomplish my goal,ask my Attorney to help me keep you notice failure for me to reach you in person. The Doctor said I have a few days to live, please contact my attorney with the following email address and phone number as soon as possible, I am finding it difficult to breathe now and I am not sure if I can stay up to two week. Name Attorney Chaplain Upright Email:attorneycchplain@... Please hurry up to contact my attorney so that he can direct you on how you will hand over 50% of the $50,000,000.00 to Charity, i really want to achieve that goal by helping the Charity organization before I die. My Regards. Mrs Judith Peters |

The narrative may change slightly from one email to the next. For example, a “wealthy benefactor” might ask the recipient to act as a go-between for a monetary transfer to a third party in exchange for a reward, as described in the email above, or simply offer a valuable gift. The message can claim to be written by either a dying millionaire or, as in the example below, a legal representative of the deceased.

Alternatively, the “millionaires” may be in good health and supposedly donating their money purely out of the goodness of their hearts. To enhance credibility, attackers can embed links to publicly available data about the individual they’re posing as.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

Subject: DONATION From: Maria Elizabeth Schaeffler <harshvardhan.lakhara@...> Dear [Recipient Name], My name is Maria-Elisabeth Schaeffler. I am a German business magnate, investor and philanthropist. I am the owner of the Schaeffler Group at Schaeffler Technologies AG & Co. KG at Schaeffler Technologies AG & Co. KG. I spend 25% of my wealth for charitable causes. Also, I have pledged to give away the remaining 25% this year to private individuals. I have decided to donate €4,500,000 to you. If you are interested in accepting this donation, please contact me for details. Send an email to: ...@gmail.com You can learn more about me by visiting the link below https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maria-Elisabeth_Schaeffler Greetings, Maria-Elisabeth Schaeffler, Managing Director, Wipro Limited ...@gmail.com |

Compensation scams

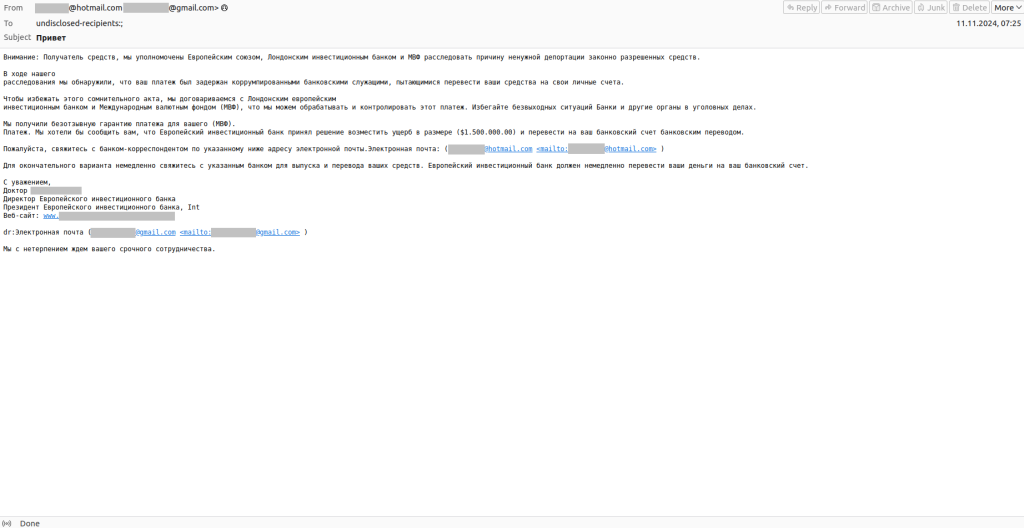

Beyond the “millionaire giveaway” scam, fraudsters frequently use the lure of compensations from governments, banks and other trusted entities. By doing so, they exploit the victim’s vulnerability rather than their greed. Scammers sometimes take their victims on an emotional rollercoaster ride. They start by frightening people with bad news, then calm them down by saying the problem has been fixed, and finally surprise them with a generous offer of compensation.

For example, in the email screenshot below, the attackers, posing as high-ranking officials at a major bank, claim that “corrupt employees” were attempting to steal the recipient’s money. The bank claims to have taken action and is offering an exorbitant amount as damage compensation. To get it, the recipient is urged to contact a correspondent bank as soon as possible at an email address, which is, unsurprisingly, registered with a free email service.

Scammers have another trick up their sleeve when it comes to compensations: they pretend to be from the police or some international organization and promise to give victims of “Nigerian” scams or other rip-offs their money back. In the example below, scammers, posing as the Financial Stability Council and the United Bank for Africa (UBA), promise the victim a payout from a so-called “fraud victims compensation fund”.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 |

Subject: Fund Ref: 110/XX/236/OB/2024 From: "Dr.John Schindler (Secretary General)" <tguil@….com> Attention My Dear, After the Global Financial Pact Summit, Monday, November 11, 2024 in Paris we have come to the conclusion to pay Scammed victim compensation fund. You are in the badge B category that are going to benefit from the world's largest humanitarian aid budgets. With due regards to the instruction from the Financial Stability Board (FSB). We want to inform you that (The Financial Stability Board (FSB)) have arranged with UNITED BANK FOR AFRICA to immediately effect your payment through the online transfer of your $1.750.000.00usd via UBA BANK online transfers. The transfer of your fund will be processed and completed within 3 working days, within which the fund will safely reflect into any designated bank account of your choice. To this effect, you're required to contact Sir.Joseph Warfel Mandy Online Banking Services, UBA BANK Email : ...@gmail.com Deposit And Fund Details Fund Ref: 110/XX/236/OB/2024 Fund Value .. $1.750.000.00 Fund Origin ..Financial Stability Board (FSB) Paying Formula.. UBA BANK Online Transfer! Contact Sir.Joseph Warfel Mandy with your Full names Direct telephone number Your identification Number Current Address He will furnish you with all necessary online information to carry out the online transfer of your fund by yourself. Please note that F.S.B mobilization and efficiency sum of $125 is the only payable/required sum to effectively complete your online transfer without any delay. Thanks and best regards Dr.John Schindler (Secretary General) Copyright @The Financial Stability Board (FSB) |

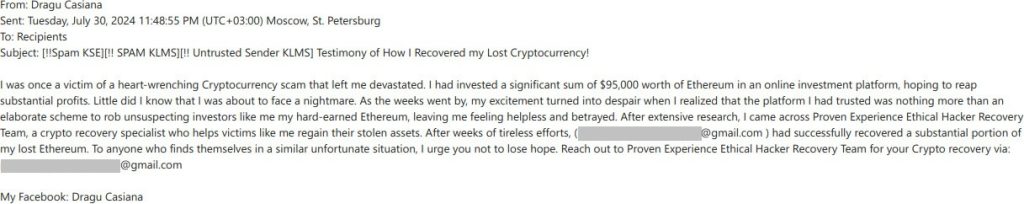

Sometimes scammers pretend to be “victims of fraud” themselves. The screenshot below shows a common example: scammers masquerade as victims of cryptocurrency fraud, offering help from “noble hackers” who they claim helped them recover their losses.

Lottery scams

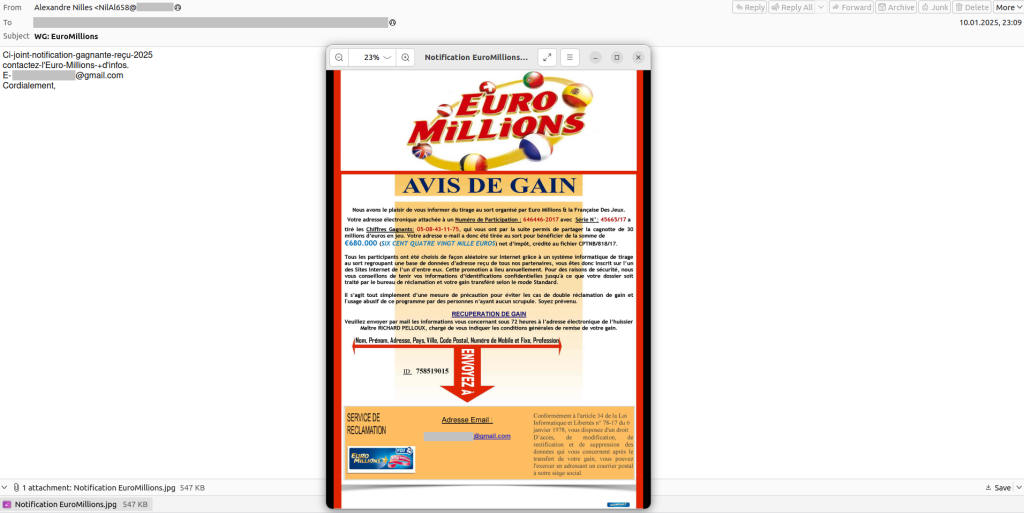

Lottery win notification scams share many similarities with “Nigerian” scams. Fraudsters promise recipients large sums of money and provide their contact details for further communication. It’s likely that the victim has never heard of the lottery they’ve supposedly won.

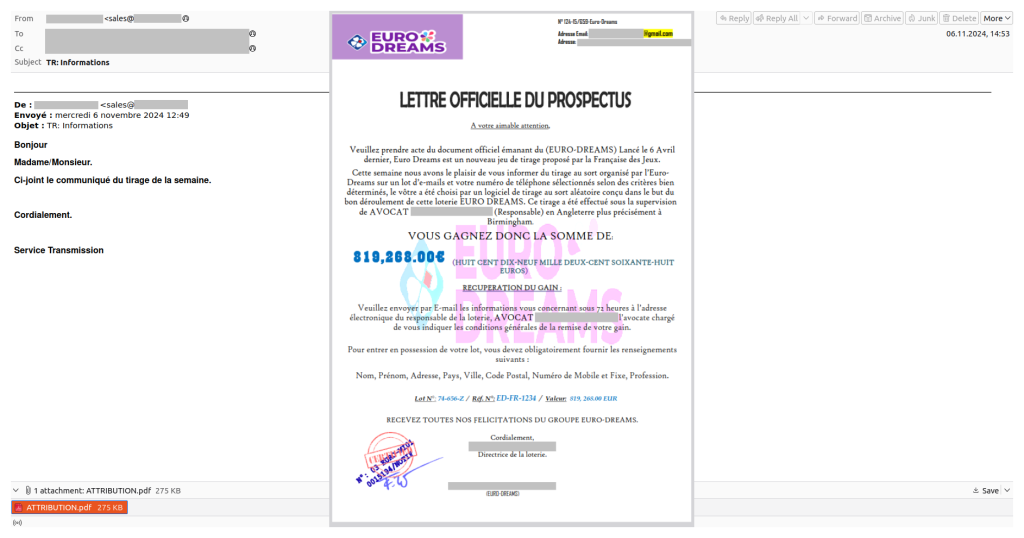

In some cases, scammers employ unusual tactics. For example, in a message claiming to be from a European lottery director, the email body is all but empty. All the “win” details and next steps are in a PDF attachment. The file includes a free email address, which is typical of “Nigerian” scams, and asks you to send fairly detailed personal information, such as your full name, address, and both your mobile and landline phone numbers. They even ask for your job position.

In other similar emails, we noticed image attachments that included all the details about the supposed “win” and contact information.

Another lottery scam tactic combines two types of bait: a lottery win (fraudsters pretend to be someone else who has won and is now offering you money) and offering a donation from a wealthy elderly person.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

Subject: Spende von €1,500,000.00 From: Theodorus Struyck <dina@...> Reply-To: Theodorus Struyck <...@gmail.com> Wir freuen uns, Ihnen mitteilen zu können, dass Ihnen und Ihrer Familie eine Spende von €1,500,000..00 von Theodorus Struyck, 65, geschenkt wurde und der Gewinner des zweitgrößten Jackpot-Preises der kalifornischen Lotterie Powerball im Wert von 1,765 Mrd. 11, 2023 , ein Teil dieser Spende ist für Sie und Ihre Familie. und diese Spende wird auch zur Armutsbekämpfung beitragen, für arme und ältere Menschen in Ihrer Gemeinde, indem sie der Menschheit helfen. Bitte kontaktieren Sie uns für weitere Informationen, um das Geld per E-Mail zu erhalten: ...@gmail.com, ...@outlook.com |

In some cases, to make their scams more convincing, scammers attach photos of documents to their emails that supposedly confirm the sender’s identity or their winnings.

Online dating scams

Some “Nigerian” scams are so sophisticated that they can be hard to spot right away. These include offers of friendship that often develop into romantic conversations, which can be almost indistinguishable from real-life interactions. We’ve seen examples of really long email exchanges where a whole drama played out. A man and a woman met online and hit it off, chatting for hours about everything under the sun. Now, one of them is finally ready to meet the other in person. However, they can’t afford the ticket or visa, and they’re pleading with their partner for financial help so they can meet.

In a different scenario, the scammer pretends to send an expensive gift to their partner. Eventually, they claim they can’t afford the postage and ask the victim to cover the costs. If the victim agrees, they’ll be hit with a series of additional fees, and the package will never materialize.

“Nigerian” spam for businesses

While “Nigerian” scams are often targeted at individual users, similar spam can also be found in the B2B sector. Cybercriminals claim to be seeking businesses to invest in, and the recipient’s company may be their target. To arrange a “partnership”, they ask the recipient to reply to the email.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 |

Subject: Potential Investment Opportunities in Russia From: Grigorii Iuvchenko <grigorii.iuvchenko@...> Dear [Recipient's Name], I hope this email catches you off guard. I am a business development professional at Sovereign Wealth Portfolio Limited. We operate on behalf of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia through the Saudi Fund. As you may be aware, Saudi Arabia is in the process of applying for membership in the BRICS economic bloc, which includes Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. As part of this process, Saudi Arabia is required to invest a certain amount in each of these member countries. I have been tasked with identifying potential investment opportunities in Russia, and I believe that you or your organization could be a suitable candidate. Whether it is a new venture, a project, or an existing business, I would be interested to hear your thoughts on possible partnership opportunities. I look forward to your response. Sincerely, Alexander Maksakov Business Development Director Sovereign Wealth Portfolio Limited |

Current “Nigerian” spam themes

Some of the spam samples above reference recent or current real-world events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic or Saudi Arabia’s possible BRICS membership. This is typical of “Nigerian” scams. There are countless ways scammers exploit various global or local, significant or ordinary, positive or negative events, news, incidents, and activities to pursue their selfish goals.

The most talked-about event of 2024, the US presidential election, significantly influenced the types of scams we saw. Emails that took advantage of this topic were sent to users around the globe. For instance, in the following message, the scammers claimed that the recipient, who uses a German email address, was lucky enough to win millions of dollars from the Donald J. Trump Foundation.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 |

Subject: DONALD TRUMP FOUNDATION From: MR Donald trump <katsuhito_ogura@...> Reply-To: ...@gmail.com Hello., this email is from Donald J. Trump Foundation, American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021. , The Trump Foundation is a charitable organization formed in 1988. As we happily celebrate Mr Donald J. Trump as 47th President of the United States. It gives me great joy to announce to you that after the winning of election, Donald J. Trump has called for the reopening of the Trump foundation which was closed years ago. The Trump foundation is giving out $15,000,000.00 each to 50 lucky people around the world to unknown randomly selected individual Emails online,the foundation simply attempt to be fearful when others are greedy and to be greedy only when others are fearful Price is what you pay, Value is what you get, Someone's sitting in the shade today because someone planted a tree a long time ago. You have been selected to receive this $15,000,000.00, as a lucky one confirm back to me that this selected unknown email is valid,Visit the web page to know more about the Donald J. Trump Foundation, https://... Contact. This email below (...@gmail.com) Best Regards Donald J. Trump Foundation |

Creativity unbound

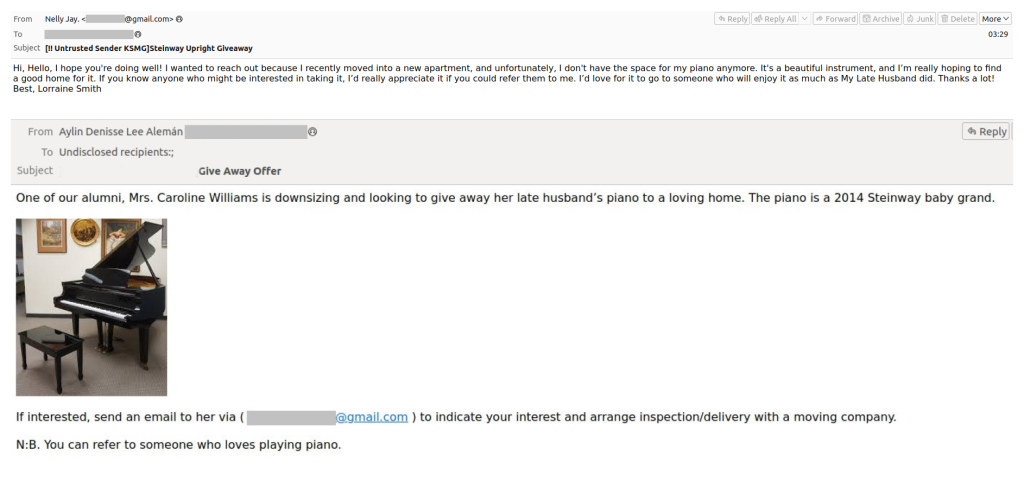

While most spam fits into well-known categories, scammers can come up with some very surprising offers. We’ve seen quite a few messages from people claiming they’re giving away a piano because they’re moving or because the previous owner has passed away, as is often the case.

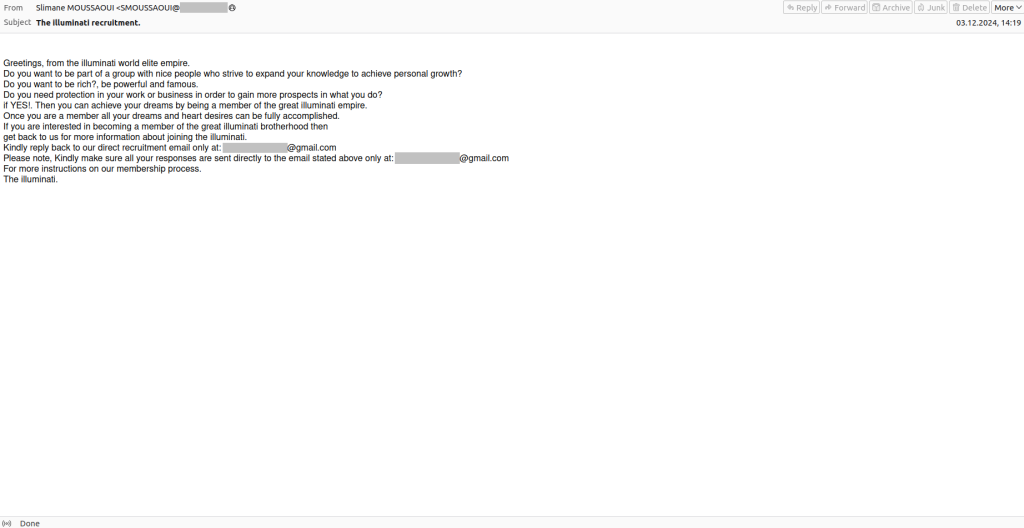

Sometimes you find some really unusual specimens. For example, in the screenshot below, there’s an email allegedly sent from a secret society of Illuminati who claim to be ready to share their wealth and power, as well as make the lucky recipient famous if they agree to become part of their grand brotherhood.

Conclusion

“Nigerian” spam has existed for a long time and is characterized by its diversity. Fraudsters can pose as both real and fictitious individuals: bank employees, lawyers, businesspeople, magnates, bankers, ambassadors, company executives, law enforcement officers, presidents or even members of secret societies. They use a variety of stories to hook the user: compensations and reimbursements, donations and charity, winnings, inheritances, investments, and much more. Messages can be anything from short and captivating to long and persuasive, filled with numerous convincing claims designed to lull the victim into a false sense of security. The main danger of such emails lies in the fact that at first glance, there is nothing harmful in them: no links to phishing sites and no suspicious attachments. Scammers exclusively rely on social engineering and are willing to correspond with the victim for an extended period, increasing the credibility of their fabricated story.

To avoid falling victim to such scams, it’s important to understand the dangers of tempting offers and to be critical of emails allegedly sent from influential individuals. If possible, it’s best to avoid responding to messages from unverified senders altogether. If for some reason you can’t avoid corresponding with a stranger, before responding to even an innocent message about finding a new owner for a piano, it’s worth double-checking the information in it, paying attention to inconsistencies, grammatical errors, etc. If the reply-to address is different from the sender’s address, or if you see a different address in the email body, this may be a sign of fraud.

Investors, Trump and the Illuminati: What the “Nigerian prince” scams became in 2024